Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

“Ag bai hungama chhaye re” — Oh woman, let it get messy1

Elham Rahmati

Thinking about what must go into this editorial, which is the first one I’m writing for NO NIIN, gave me some degree of anxiety. Why have we chosen to start this magazine and what do we want to achieve with it? Since this question has already been included in the magazine’s ABOUT section, let me try diverting the question to why I am here. I don’t entirely feel comfortable with the title of a “co-editor”, although, it brings me solace when I think about who I’m co-editing with, NO NIIN’s co-editor, Vidha Saumya.

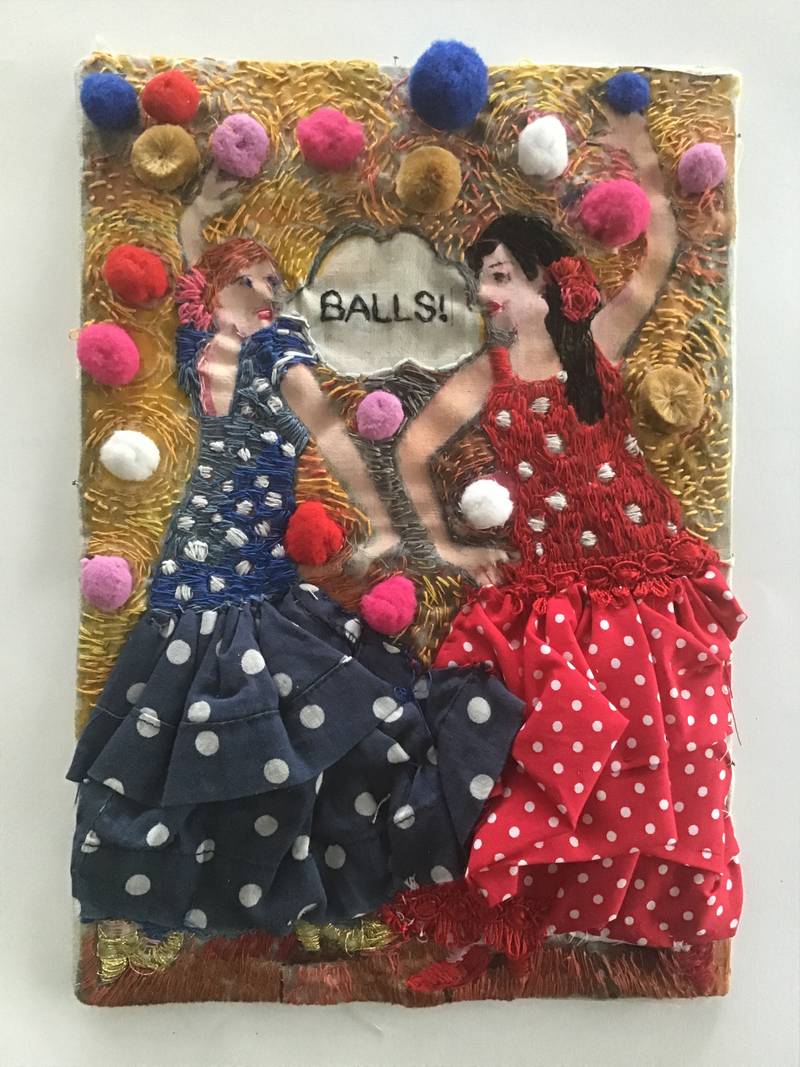

Mary Stockton Smith, Balls, embroidery, fabric balls, acrylic paint, 27 x 18 cm

Balls was showcased in the online group exhibition of ‘PEG - Profanity Embroidery Group - Whitstable’ of which Mary is a member. PEG has offered me a different audience and approach as well as the company and support of some very rude women and men.

I thought about what it means to start this journey with Vidha. My own tendency is to be wary of “collaborations” as in the past they have been challenging and at times painful, to say the least. I have lost count of the number of occasions where I didn’t feel cared for, heard or valued; the times where I found myself fighting others’ battles and ignoring my own, the moments where I wasn’t treated with the honesty and respect that I deserve. Whether I have addressed them or left them unaddressed, these are all burdens I carry along in my growing professional life.

In an age framed by the centrality of a capitalist economy that has bled all over the art world, we often find ourselves working for/with institutions who are clearly more inclined to tend to the art projects promised to them, rather than the art workers implementing them. There are different sets of methods and procedures predicted to follow up on the progress of the project and to make sure that it is being fulfilled according to the plan and yet there are next to no mechanisms defined within the institutions to protect the art workers against misconduct, harassment, assault, bullying and abuse that they may experience while working on the projects commissioned or funded by the institutions. Being mostly reliant on the financial support of the said institutions compels us into adopting their priorities. This bankrupt structure is why so many of us end up putting our projects above our own mental and physical health, above the well-being of our friendships, our relationships and our colleagues. Then, before you know it, one day you find yourself supporting Black Lives Matter on your Instagram account while in your artistic practice you reinforce the capitalist mentality that has made you believe it’s fine if you step over your friends and colleagues to get ahead in your careers, it’s fine if you overwork them, it’s fine if you don’t pay them for their work and just offer them visibility, it’s fine if you don’t credit them properly, it’s fine if you don’t bother to clarify their rights and job descriptions in a contract, it’s fine if you manipulate them to think all of this is OK, that this is all justified in the name of “the project”, the end product that must please our funders if we want to continue working and surviving.

I wish to find a way for myself in understanding how artistic exchange can operate as an avenue for navigating immediate crises, precarious lifeworks, and unstable futures. I want to put in practice the knowledge that “care is about feeling with others, rather than feeling for others - about working with others, rather than for others”2. I want NO NIIN to be a fresh ground where I can put to test all that I keep telling myself - that which I have learned from these fairly bitter experiences. Not to celebrate them or be grateful for them (like Sansa Stark did distastefully in the last season of Game of Thrones (cannot and will not let that go), (also not comparing my troubles with her traumas but you know what I’m getting at)). I want to dedicate this first editorial to one thing and that is a pledge I wish to make to myself in regards to my collaboration with Vidha, as I believe this collaboration to be the foundation on which we are building NO NIIN upon. I don’t know how long this project will last, what I hope for is that at the end of it I’ll be as fond of Vidha as I am now, if not more. So, I make this pledge to myself rather than to her, as it should be my job to follow through with my promises, not hers, and also because abiding by these promises is an act of self-care which I do owe to myself as “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”3

In an age framed by the centrality of a capitalist economy that has bled all over the art world, we often find ourselves working for/with institutions who are clearly more inclined to tend to the art projects promised to them, rather than the art workers implementing them.

So here it goes:

Sometimes, during tasks that need joint decisions, I catch myself putting out final statements without offering the thought process and the rationale behind them, thereby making it the other person’s job to figure it all out by herself. This makes the work exhausting for everyone and I want to feel nothing but joy in NO NIIN. So I promise myself to try and do a better job in unfolding the reasons behind my ideas. Not to imply that all my ideas are so brilliantly complex and genius that one can’t understand them without me spelling them out. It’s just that without offering reasons you are leaving the other with a list of Do’s and Don’ts and this is no way to treat a collaborator, whether you have defined yourselves to be sharing equal grounds in terms of authority or in situations where one holds a higher position in the hierarchy of a collective or an institution. Luckily, our dynamic is not one of the sorts.

I promise to always share the best of gossips and stories I come across with Vidha. Mainly because she always comes up with the funniest and most cutting comebacks and responses that keep me laughing the entire day.

For the sake of our sanity, I think we should dedicate at least half an hour to Bollywood themed discussions in the midst of our work meetings. Nothing takes the pressure off work like watching a video of Ranbir Kapoor dancing naked around the house with a towel4 or Rani Mukerji lusting over the six-pack guy in Aiyyaa.5

I promise myself to remain cautious of projecting whatever hurt or mistrust that I still carry as an outcome of my previous collaborations on Vidha or any other person I’ll come to work with in NO NIIN.

There is no art project in the world important enough to trump a person’s well-being. I promise myself to never expect Vidha or any other person I work with, to overextend themselves and their limits, in relation to our work together, in the name of friendship or comradery.

I promise to keep updating these promises as we move further in our work.

Frustrations and misunderstandings are inescapable in any collaboration, no use pretending they will not come up here and there. I promise to myself that I will address things as they come up and I will do so with the utmost kindness and clarity that I can afford, keeping the sharp-tongue, sarcasm and bad-temper at bay as much as possible (maybe adding only a touch to spice things up). We have both found it a good practice to always sleep on the issues that bother us at least a day or two to calm the rage or resentment that cloud our vision and judgement.

In the spirit of the previous note, I promise to remind us of this quote from our beloved Shahrukh Khan in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge6 every time either of us makes a mistake:

Bade bade deshon mein aaisi choti choti baatein … hoti rehti hai.

Bade bade: big big

Deshon: countries

Mein: in

Aaisi: such

Choti choti: small small

Baatein: things

Hoti: happening

Rehti hain: keep

In big big countries such small small things … keep happening.

Where are you from? I am from Puotila

Vidha Saumya

When we gleefully agreed to meet outside the Finnish Immigration Service point we had an elegant plan – a collection of mental notes – Migri1 door opens - collect tokens - have breakfast (still looking for cafes that open at 8 am) - back to Migri - prove identity - hop over to Cafe Pequeño - email our board members for the first association meeting - have a hearty MSG-laden buffet - visit three exhibitions neatly listed on our Trello to-do-list - close the evening with an exhibition opening. Optimistic and prepared, we didn’t make an effort to reach before time because the customer service provider had advised, “Unfortunately because of this Covid-pandemic, we are not giving any appointments but if you go to the Finnish Immigration Service point at 8am, you can get a token and prove your identity”. So there we were, Elham and Vidha, in high spirits, ready with our grant letter, confident about our residence permit for the next two years.

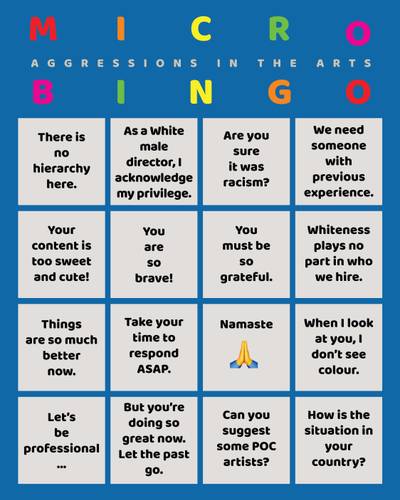

Two minutes into the queue we knew we were late, and within twenty minutes we were freezing our toes, cursing every politician, rhyming words to form bad poetry, expressing our frustration over white male curators and their industriousity, and with every tch tch and broken gasps we regretted moving to Finland. To avoid passing out, we took turns to enter the next building’s lobby to warm ourselves before returning to the queue. And yet, after three hours in -13° C, neither our resentment nor Käenkuja 1B’s lobby could adequately warm us. Just as we were about to give up our morning dream, the security guard stepped out and asked us to neatly line ourselves so that he could get a headcount and ascertain how many of us stood the chance of getting a token that day. It boosted us enough to sigh in relief and feel mighty proud of not having quit. After around three and a half hours of waiting, incessant complaining, and empathetic eye contact with others in the queue, we rushed into the indoor waiting room with our tokens. Sitting down in the passage between the two rooms of the service centre we were almost ecstatic seeing the others from the queue line enter the waiting room. Here we waited for another two hours for our token number to be announced, but now we didn’t mind it at all.

After the needful showing of papers, when we left the building at 14:15, it felt like a new day. There was no queue outside the service centre – not even the remnants of our slowly moving footsteps – a velvety layer of vitilumi2 had covered all the happenings of the morning. The sun was out, the breeze was gentle, and as we walked towards Lie Min for our Sörnäinish lunch, we were almost giggling. Funny, it was the sensation of optimism and hope that it made the mind quickly forget the anger that seethed throughout the morning. It was as if the morning’s anguish had somehow transformed into survival, where, implicit in survival is joy, mobility and effectiveness3.

Structural gatekeeping, however, is invisible. And, it is exhaustive. It is a cascading relationship based on the educational degree, financial soundness, individual prolificity, contract clauses, and an array of fault lines that precariously hold us ‘in our place’.

The power of the state which many ‘outsiders’ like me cajole, caress and resist is not a binary of ‘you’re in and you’re out’. It is not the security guards, the ones who are the targets of our ire, who are the real issue, in fact, they like our allies offer communication, empathy and eye contact. Structural gatekeeping, however, is invisible. And, it is exhaustive. It is a cascading relationship based on the educational degree, financial soundness, individual prolificity, contract clauses, and an array of fault lines that precariously hold us ‘in our place’. Artists, art workers, students, and academics find ourselves constantly pitted against each other trying to find our curbs and perform outstandingly, repeatedly. These repeats are doubly difficult for those who cannot afford recovery. It causes those of us who have to queue up overuse4, overtraining5 and a cerebral overpronation6. So how do we, two brown women, find our joy in this vast white sea? We find it by laying open the fault lines of the “where are you from?” brand of the contemporary art scene that suffers from a tendency to maintain gatekeeping, thereby allowing selective nurturing, and problematic promoting of artists based on market performance and individual productivity. In our planning, preparation and working at NO NIIN, we are finding ways in which we can prolong our Talk Test7. We want ourselves and our contributors to work at a comfortable effort level. During most of our work, we should be able to carry on a conversation. Speedwork8 is necessary but if we find ourselves exhausted and can’t offer care and attention we back off to where we can restart the sentence. We foresee that this back and forth will allow us to carry out our work for longer while preserving our energy, our relationships and what NO NIIN is to become. Our work is not separate from the life we are living: it is threatening and at the same time very very satisfying. We want to spread out through this platform, learn by working, and put out questions about what we don’t know.

We are flawed and full-on afraid of approaching and in dealing with ourselves, and the world. And so sometimes in Shah Rukh Khan, we find hope. In a recent interview show9, Shah Rukh Khan says, ‘If I can’t do it with the skill and talent, then let me get into the hearts of people. And if they’re loving me, let me just be nice and good about it.’ In a tribute to Shah Rukh Khan on his 50th birthday, Paromita Vohra quotes from one of Shah Rukh’s interviews where he says one of the things he’s learnt from his father is mehmaan-nawazi10 – that when someone enters your space, you make them feel good. And in this way, he represents a way of being, a way to be hospitable11. This joyous hospitality makes the idea of success an intangible miracle that blooms like a spring flower or shoots like a star. I have only recently converted to being a Shah Rukh fan, courtesy NO NIIN’s co-editor and co-founder Elham Rahmati, with whom I am having the work-life that I have only dreamed of until now. These are a few of my favourite things I do at NO NIIN: savour every thought that comes to my mind, read relevant and random zines, anecdotes, jokes, gossip, memes – all ‘low’ materials, reading them as if I am reading theory PDFs written by dead white men, with dead seriousness and an over-analytical mind and trying to locate ‘why I like what I like’ among them. I welcome our readers to find in NO NIIN that bittersweet miracle of seeing a space where we are always collaborating in revealing invisible fault lines, joys, and care for others, and where the role of the writer, artist, curator, and the reader keeps getting interchanged.

Kisne kaha ki chamatkar nahin hote, zara mujhe kareeb se dekho.12

Kisne kaha: who said

Ki: that

Chamatkar: miracles

Nahin hote: don’t happen

Zara: just

Mujhe kareeb se dekho: just have a closer look at me

Mujhe: me

Kareeb se: closely

Dekho: look at me

Who says that miracles don’t happen, have you ever looked at me closely?