Image: Koshy Brahmatmaj

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

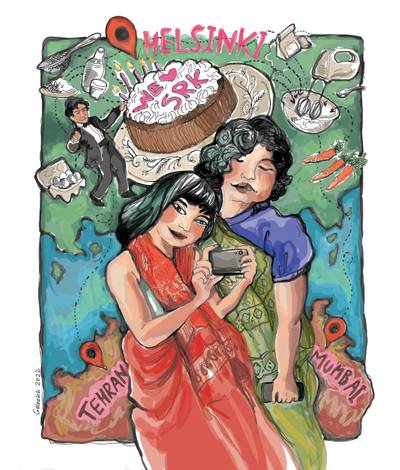

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

Imagine the Communities We Are Yet to Become

Elham Rahmati

This week I was invited to speak on a panel discussion titled ‘There is no single-issue struggle because we do not live single issued lives’, along with Majed Abusalama, Boodi Kabbani and moderated by Maryan Abdulkarim. This was part of the #StopHatredNow 2022 – Practising Coexistence programme organised by Urban Upa (major thanks to the amazing Sonya Lindfors, Lisa Kalkowski and Essi Brunberg for providing us with such an inspiring platform). I was quite hesitant about whether I should participate or not, mainly because of my fear of public speaking. But then I figured this would be online, and I wouldn’t be seeing anyone other than the host and panellists. And if I received the questions from Sonya and Maryan in advance, then I could write down my answers and have them as a script in front of me, and so I did that:

For us, as for many others, Lorde’s statement, ‘There is no single-issue struggle because we do not live single issued lives,’ has been a guiding force. How do you understand/approach intersectionality in your practice? How do you relate to Lorde’s statement?

Lorde believed strongly in building worldwide coalitions with people of colour: to her, we are all members of an international community of people of colour, and we must see our struggles connected within that light1. Having said this, she also insisted that it is the refusal to recognize and accept differences, not the differences themselves, that separate people. We can’t build the supportive communities necessary to effect social change without first affirming these differences. The need for community is something non-negotiable for Lorde, as “without community, there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppressor.”

In her quintessential book, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, Lorde writes that, "As women, we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change.”2 In my professional life, I’ve grappled with this. If your practice has anything to do with building communities and if you happen to have received some funding for that work, then inevitably you are going to have to face these suspicions and be confronted head-on with the lines of difference that have separated us. You are going to have to dedicate a lot of time and energy to first and foremost proving that you are doing whatever you are doing because you believe in it; that you are not just using other people’s struggles to promote yourself. It is a fair expectation, and I’ve had it from other organisations myself, but at the same time, I understand how demotivating and frustrating it is to be faced with suspicion and expectation right off the bat instead of hope and support from those you feel connected to in terms of living on common grounds. Again, I understand why this is not always the case. The more you’ve been discriminated against, the more hypervigilant you feel you have to be. I haven’t found much resolve yet in terms of how to navigate myself through these waters, other than just carrying on and hoping that the sincerity with which we work comes through over time, and maybe that would help push the suspicions aside.

How can intersectionality be practiced? Do you have some concrete tools or practices from your current working context?

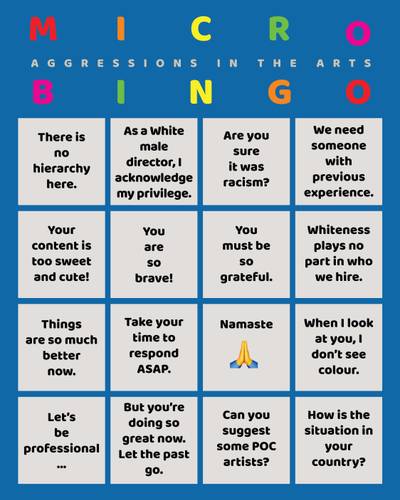

I think one must start by learning what intersectionality means in the first place. I can say with certainty that most people working on a permanent basis in public and private art and cultural institutions here—and assumingly most other European countries—don’t have the slightest idea of what intersectionality means. Imagine up until, let’s say, ten, or fifteen years ago in Finland, art students could go through an entire academic education without even once hearing words like intersectionality. The same people now have access to the majority of funding and resources, which they would rather spend on promoting the kinds of artistic practices and cultural activities that fit within their limited frameworks of what art is and what it can accomplish. This leaves us with the least creative and most problematic results. These people are also highly resistant to change, and they can very well afford to be because, from their point of view, there is only a small niche of art workers who will be critical of their uninspired working methods. And we all know who those protesters are: art-workers from Afro-Finnish, Sámi, immigrant, working-class, disabled and other disenfranchised communities. It is so rare that white middle/upper-class Finns join the said groups in voicing their criticism alongside them. They might sign a petition or two or even write to you and thank you for all the work you’re doing, which I find patronising because when you ask them to join in and echo your voice, they say, “Oh, we’re so tired, we are so overwhelmed, we need rest” and other excuses like this. At times, we have invited white Finnish artists and curators to, for example, address the racist structures upon which the commercial Helsinki art scene is built or to write critically about how certain funding bodies function for NO NIIN. The answer we receive most of the time is, “oh, no, we’re so tired, we’re so overwhelmed, we need rest.” If Lorde advocates caring for oneself as an act of political warfare, I doubt it’s you that she’s talking to; what you need to give a rest to is your sense of entitlement. I firmly believe these days that no amount of diversity/anti-racism training or consulting can resolve what is clearly a lack of feeling towards those who don’t share your race, socioeconomic, or residence permit status. I’ve had it with all the politeness and patience with which we deal with those who don’t even see us as humans.

What I want to employ and advocate for as a concrete tool in my work is this: no more shying away from conflict and more being demanding towards those whom I know can afford to take part in difficult conversations and not give them any more breaks than necessary, especially those of them that build their careers on claiming radical politics.

With NO NIIN, we have tried to create a space where our voices can exist in parallel and proximity to one another without necessarily being in consensus. Here in Finland, I sense that our communities are quite strictly exclusive to members of their own. I hope for a day when we can make each other feel safe enough that we’d want to open up our communities to each other, to fight not only our own battles but also each other’s, and reserve whatever amount of patience, empathy, and understanding that our lives afford us for each other and not for our oppressors.

– This is a bit hard to formulate, but I have been devastated by the blatantly different reactions to refugees from Ukraine, that is, white refugees from Ukraine. I have been thinking about solidarity and proximity. Can people in privileged positions only feel solidarity towards sameness? Do you think race is a factor in how refugees are treated?

Thinking about the relationship between solidarity and proximity, I’d have to go back to the education that people receive, which represents the governing bodies and the ruling ideology at large. Capitalist/neo-liberalist systems not only don’t bring about any form of emancipatory thinking, but they make sure to oppress it. In more clear-cut authoritarian states, this is done through physical force and violence. But there are other states, like the Nordic states, that are cunning in more disguised ways, like how they indoctrinate what I think is best described as an unimaginative and unfeeling way of living and thinking. Accepting the order of things as they are and have been. And this isn’t just a matter of proximity to power in terms of race, but class as well. You assume that the inequalities the working class is suffering from are theirs and their problem only and that they will never affect you. I have met Finnish people in academia who believe there is no class struggle in Finnish society. As for solidarity toward Ukrainian refugees, I believe most red carpets and special treatments were performative acts. European solidarity acts are momentum-based; once it’s gone, so is the support and kindness. I mean, look at how Germany exploits Greece, for example. It’s not humanity that is a determining factor; most of these so-called humanitarian actions are mere power/market-driven gestures.

– Let’s end with dreams. What would a truly intersectional and diverse art institution look like?

Art institutions, as they are and have been, are where dreams go to die, even the most intersectional and “diverse” of dreams. So I rather not waste my imagination there. Instead, I want us to find ways out of the loneliness and narcissism of our “art scenes”, to imagine the art communities we are yet to become: internationalist communities of anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperialist art-workers working towards building transnational, feminist, non-transactional solidarities that actively question unequal power dynamics and push for cultural, economic, and political transformation in our societies, in defense of indigenous self-determination, socialist revolutions, civil rights and Black liberation, working-class unionization, LGBTQIA+ movements, stateless nations, undocumented migrants and refugees organizations, disability rights, and climate justice.

There’s no cake in your gateau, there’s no verb in your motto.

Vidha Saumya

Cake fakes are rampant in Helsinki. To be more specific, they are kind of cake doppelgangers and can be spotted from afar. They are loaded with mousse, compotes, cream, colour, and flavouring, but never enough cake. The gelatinous gloss on these cakes is tempting, but it’s all for nought. For all the panache in the marmalady ganache blanketing the cakes, the spongy, airy, quilty bread-like layers are missing. There is no cherry on the top of this gateau travesty – these cakes are as expensive as they are disappointing.

Should cakes be like that? When you arrive from a supposedly not-a-cake country from the Global South, you expect to be enthralled by this Western mithayi’s delectable decadence, but it turns out lousy, and the only reference you have is your not-a-cake-country cake. So, you immediately resign to, ok, maybe I am wrong. Perhaps, I don’t know what a good cake is. Food experts and those offended by my selective appetite may argue why not try pulla, lörtsy, rönttönen, Runeberg torte? But I don’t want to talk about the comfortable, accessible, earthly delights. Mind it, those are not cheap either.

Whether you like cake or not or argue about why I shouldn’t expect good cake in Finland in the first place, I think about Finnish society’s self-proclamations of internationalism, benevolence, and neutrality in the same breath. I also wonder why African Tähti is sold in shops here (even in the design museum), why there are no non-white, non-Finnish tenured professors in the universities here, and why there are no permanent non-Finnish employees in positions of leadership in the institutions here OR why the calls for sanctions to Russia are as loud and repetitive as their silence and neutrality on Israel’s occupation of Palestine.

When you notice discrepancies, you want to discuss them. When they say, “Choose your battles”, you want to reply, “I choose all of them”. But no one can speak up all the time on all the issues. We also fear consequences. Keeping oneself afloat and breathing in an overstimulated and oversimulated world is already a feat. One would lose one’s sanity if one retaliated to all the privilege-bombing that people with bounteous resources do. In such times, like a rug taken out to dust before summer, these privileges must be dusted off to reveal their true colours or the constituted and authorised powers granted to selected individuals in a society. A society is accountable to its citizens, particularly when these powers are exercised with manifestly disproportionate discrimination and repression.

When I responded to these issues by writing poems during my first years in Helsinki, I saw them as personal musings. They held the possibility of becoming public, either through reading or publishing. But initially, they were private thoughts. Once performed, they became public statements. This gave me confidence. Nowadays, I have a publishing space in which I can write an editorial. An editorial is even more public, and it is taken more seriously because of its format. I am one of the two editors, and each time I sit down to write or make notes for the editorial, I hope that it gets read but also that through the process, I learn something I did not know before, and the learning is not just about myself. Even though the writing comes from specific personal experiences, it is a journey to gather familiarity with the unknown. Being an editor allows me proximity to freedom and creative excitement. My editorial “day job” is no different from “my own practice.” Friends and well-wishers often ask me, “do you get time for your own practice?’ I want to reply, “It’s not someone else’s practice that I do with NO NIIN.” I understand that they mean whether I get time to be creative. Perhaps the editorial space where I have spoken at length about the administrative woes and joys of running a magazine is something they refer to as not being artistic enough. Just as I will never know how to bake a cake (nor do I desire to), it is beyond me to understand the neat categorisations of the creative and administrative. Using food examples to explain and understand something offers me analogy and metaphors – the kind of nuance otherwise possible only with poetry. Cooking in this regard is the coming together of the creative and the administrative – it is very much imagining something that’s not there, linking things that previously had not been connected. I can see the connection between the two and that they similarly satisfy that dreamy, imaginative part of myself.

I had the best cakes in Helsinki at the Arthouse – Aalto’s art school premises with studios and classrooms + a well-equipped kitchen available for students to use. A good cake IMO is gluten and lactose friendly and comprises almost wholly fat, sugar, flour, patience, and love, smeared with a generous amount of frosting, ganache, and marmalade. Saša, Kathy, Noura, Kuba were excellent at baking, laughing, sharing and conversing. A cake of carrots and cardamom. A cake of coconut and pineapple. Or walnuts and dates. A Sacher-Torte.

Six years of living here have not abetted my desire for cake. When I think of cake, I believe Helsinki’s gateau industry underwrites it: mousse, gelatin, fondant and marzipan. I crave the giddiness of the fluffy, spongy delight, which the insatiating cream-laden structure called kakku makes me miss dearly.

Cooking is central to my meaning-making of the world. I’m not the best cook, but I can follow a recipe, and I understand the logic of flavours and heat. Among all the “side jobs”, cooking is my favourite. I have close friends equally passionate about food and its politics. We’ve often shared recipes and stories about something so intimate.

Like any other joy, cake is also a capitalist endeavour and a divisive subject, not only because of the variety of flavours but the politics of what it brings to the table. You’re putting together ingredients that are entirely different from each other and letting them fight it out, not on their own terms, but in terms of neoliberal commoditization and attention economy.

As I said before, you can’t really get a good cake in Helsinki unless you can make it yourself or are fortunate enough to have a friend like Saša. Or Kathy, Noura, Kuba. So the cake is connected to communities that form to bridge the apparent and perceived cultural and political gaps. The consistent efforts made by such groups, formed mainly of immigrants, BIPOC cultural workers, and students are saturated with significance even if they may not be officiated to be considered relevant. The work done by the intersectionalists are not catchy, easy to quote definitions but they attend repeatedly to expectations from within and outside, and play a relevant but unacknowledged role in how the art and culture scene is shaped in the most urgent and intimate ways.

Are the long to-do lists of artists and cultural workers the real cake, so to speak, and how can their work be forefronted, acknowledged, credited, critiqued and be turned into policies that create an equitable scene? What’s the work that goes into continuing the onward journey to such a cultural destiny? The answers can’t be written down as a neat recipe. The proof of that cake will be simply in eating it.