Sepideh Rahaa, still image from One Ocean Is the Distance, 2015

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

Quit your jobs!

Elham Rahmati

There are art institutions here that once in a while take one step forward, which cheers you up and gives you a bit of hope, but then comes a decision that is the equivalent of ten steps backwards and leaves you banging your head against a brick wall (the one Sara Ahmed has wisely warned us about). In the second issue of NO NIIN, we published a letter addressed to Frame Contemporary Art Finland, written by Farbod Fakharzadeh. There he brought up his frustrations with the institution and its disappointing ‘speed of change’. Farbod, at the end of his letter, presents a solution to Frame and all other institutions that claim they are attempting to learn, do better, be more inclusive, bla bla…

“If you’ve worked for more than five years in a leadership-level position in an institution that seems to continuously struggle with the issues that are raised by this text (most cultural institutions in Finland), and you really want to help change things for the better, please quit your job! You’ve been in your position long enough and your efforts don’t seem to really create meaningful changes. By giving up your position, you at least may have contributed to a new beginning.”

At the time, I read this more as a tongue-in-cheek dig at white institutions and not so much as a viable solution, but now, a year after, I’m thinking, “damn, he was right! They really should quit their fucking jobs!”

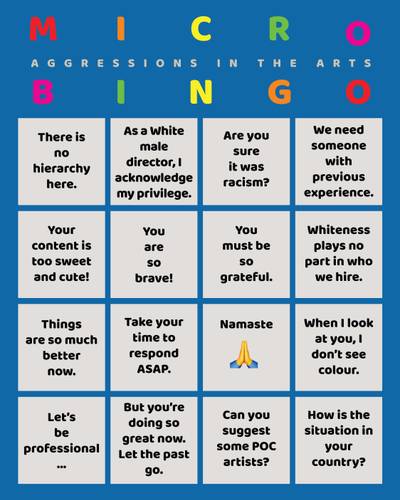

With no citations at hand and just because I have a functioning set of eyes, I’d say that 99% of curatorial/artistic positions at arts organisations and institutions in Finland are hogged by white people. Art institutions, such as museums, shape and valorize the art historical canon by building and exhibiting their increasingly neoliberal collections. Their position of power provides (financial) stability, a large staff, and large audiences, which allows them to secure more and more funding. In Finland, the employees of such institutions generally have permanent contracts, which gives them long-term power in decision-making, programming, and resource distribution. Yes, they may invite you to participate in their exhibitions and they may curate their programming around your struggles (ARS22), but have they built a workforce that is as representative and culturally diverse as the exhibitions that they seem interested in putting up once in a while? The answer is, “Fuck NO!”

Even the smaller organisations that clearly have difficulty raising money, lack innovation, and can’t figure out how to grow their audiences, don’t budge to give space (and by that I mean to give at least a 5-year working contract, not just invite them on a panel talk) to non-liberal BIPOCs who have a vision, know how to plan, raise money, or attract audiences. The fear is real, and it’s not going anywhere.

OK, let’s get real. You (white permanent contract holders who’ve been hogging institutional jobs for decades), I genuinely believe, like Farbod did, that if you have any real interest or will in being anti-racist and inclusive, you must quit your jobs and then make sure that you are replaced by a non-neoliberal, non-complacent member of BIPOC communities. Hire a communist black woman and see if that will kill you. It won’t, but I promise you that it will be the most exciting and meaningful thing you’ve ever done in your long career. Even writing this demand out is putting a smile on my face, imagine it turning into a reality. Oh, the fun we’re going to have in this art scene then!

You (white permanent contract holders who’ve been hogging institutional jobs for decades) can never be an instigator of change–at any speed–by holding on to your positions. I bet you’re tired of constantly being called out and then having to write a statement saying, "An equal world is not ready and we too are learning the answers and boundaries to the questions that the social debate raises.”1 Can you learn on your own time and let those who have already educated themselves take your positions? Of course, I can’t say with certainty, but again because I have eyes, I think most of you come with some level of generational wealth and savings that can allow you to quit your jobs. I’m sure you’ll be fine. Even if you weren’t for a while, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to first-hand experience the precarity with which the rest of us are living here. I hear you like role-playing your way into the working class and then turning it into art projects and museum shows visited mainly by the middle/upper classes.

I heard from one of the art workers I know that they had recently had a meeting with one of the major funding institutions here and asked them to distribute their wealth by giving artists shares from the foundation. I couldn’t stop myself from laughing at first. For some reason, it made me think of “comrade” Britney calling for strike and wealth redistribution. Later, though, I did appreciate the gesture because, why not? We need more “outrageous” demands, visions, and dreams. Repetition is key, so dream outrageously and then keep talking about it. Mention it in all your conversations, social media posts, and grant applications (ok, maybe that’s not so smart). One day, it will stop sounding outrageous and start sounding like the common sense that it is.

Wishing you a great summer ahead, and enough money in your pocket to buy a copy of NO NIIN Volume 01.

Bilingual, I Love Yous

Vidha Saumya

Walking past the central railway station one evening in Helsinki, I heard a familiar melody on the accordion. Humming along, Aate Jaate, Hanste Gaate, I wondered where this person had learnt this song only to realise that they were playing, I just called to say I love you, composed by Stevie Wonder in 1984 and not the title track from the 1989 superhit Hindi film, Maine Pyaar Kiya. Both songs are about professing love. I just called… is terse and straightforward where the singer addresses someone over the phone to let them know he loves them. There is no acknowledgement from the other end. The Hindi version, on the other hand, is made up of lyrics that hold together a confession, a proposal to be considered, and is reciprocated by the second voice, not only acknowledging the proposer but responding with the realization that they are in love with each other. Meaning and intention aside, I kept thinking about this coincidence of recognising a melody and its connection to language. One does not affect me, and the other makes my heart flutter.

Using the analogy of music as the bridge between two languages, I think of NO NIIN as the space continuously creating different potential cultures. Just like melodies start to feel familiar even when you don’t follow the lyrics, the magazine’s publishing space is like a playlist of ideas that may not be in our immediate vicinity or concern but can slowly become familiar. Of the 35 music playlists on Elham’s Spotify at NO NIIN’s office, a playlist is always on. The songs range from Arabic to Farsi to Italian to Spanish and English. I don’t understand most lyrics or recognise the words, but from repeatedly listening to these songs, I can hum along and occasionally gasp at their lyricality. Sometimes they create a mood, and at other times cater to a mood.

But the openness to different languages afforded by musicality is not so open when language becomes a bureaucratic pawn. Fluency in the working language (often national or official) is one of the central and standard requirements in most workplaces. It is no different in Finland, where Finnish and Swedish language skills are mandatory for most jobs. Language is considered or is at least made out to be the main barrier that prevents non-Finnish speakers from getting jobs in Finland – more so in the field of art and culture. Less than few work opportunities in Finland’s art and culture scene are open to non-Finnish speakers. Even though English is an acceptable language of work, it is often predisposed to native English speakers.

During my ViCCA years at Aalto (2016-18), in one of Max Ryynänen’s courses, my classmate Aman Askarizad presented a song on this setar. Aman is an artist, photographer and producer, and his artistic and curatorial practices revolve around visual arts and music. Before playing the instrument, he said, “I will sing in Farsi. And I will not translate. Many of you will not understand what I sing. But ignore the not understanding of it. Instead, try to familiarise yourself with its sound.” This remains an emblematic lesson to remember whenever I have difficulty habituating myself to something new. It also gave me the confidence to boldly poise Hindi sentences in English poetry without hesitation or apology for not being understood.

There is no denying that language, spoken and unspoken, creates intimacy with their familiarity. In Helsinki, I often find myself eavesdropping if someone is having a conversation in Marathi. Marathi reminds me of Mumbai, my hometown. Languages connect us to people but also places. I feel deep affection for Lahore, a city where I honed my Urdu and got better aquainted to Punjabi. During my stay in Lahore, I was often asked, “Tuadda pind kedda aye” (which is your village?). This question never felt othering, quite opposite of how the question ‘where are you from?’ feels here. Is it because it didn’t have the undercurrent of “why are you here?” The abrasiveness of a language often comes from how another person acknowledges your presence.

Language and intimacy are also tied to the truths that come from our unique experiences in different cultural and geographical locations and cannot be homogenized. The audacity to represent change, move forward, and not stand still is often understood as a position of someone who may have nothing to lose. Working with several writers and artists, particularly in NO NIIN, I confidently conclude that only those with something (and sometimes a lot) to lose make an effort to care and are willing to withstand the isolation of not being part of the acceptable debate or consensus; rejecting yea-saying and proceeding without hesitation, unafraid of disrupting the status quo or upsetting fellow members. There is enough time wasted already worrying about politeness and selective political correctness that restricts our thoughts and contains our imaginations. If utopia exists, it must first exist in one’s mind, and must be fueled by love and affection. Hence, we must find the most intimate language to tell that truth. In that sense, the editorial language of NO NIIN is between the pleasures of experience, intimacy and truth. On days when the existential dread that I don’t know anything comes knocking, I open Youtube with playlists of Hindi songs and take delight in singing along. This vast knowledge of hundreds of songs, lyrics, meaning, and melody have no great use for the drawer publisher I am. But I am also a person with emotions, and this emotional balance is taken care of by these songs.

This month NO NIIN completes 18 months of publishing, marked with an annual publication that brings together a selection of contributions from the 150 or so we published in 2021. I think of it as a utopic combination of imagination, ambition and great design that brings together transcultural readings and self-reflection in the form of a publication. NO NIIN holds the capacity to bring intimacy and the habit of following through, like in love and friendship.