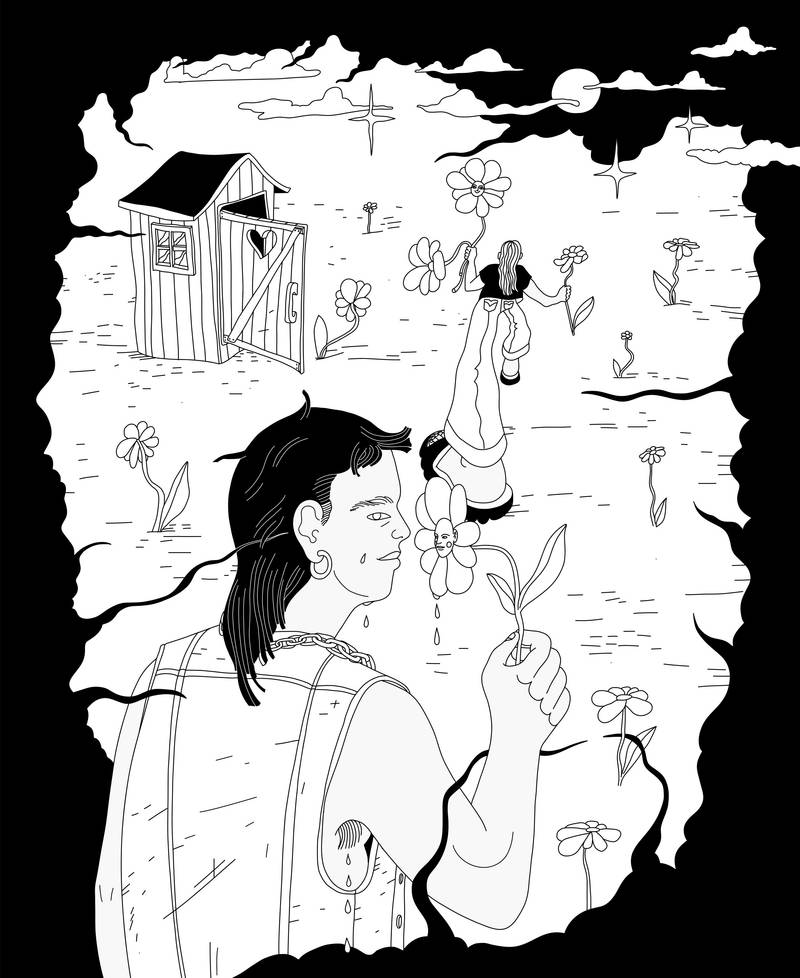

Illustration: Edith Hammar

Johanna Valjakka (b. 2000) is a freelance writer and world literature student based in Helsinki. In her writing she explores themes of representation, intertextuality, social issues and the human psyche. Having a passion for climate activism, she pursues to capture the beauty and importance of nature in each of her texts. Alongside writing and literature, she enjoys film marathons, hiking and playing chess.

The abandoned skin of a smoked salmon lies on a dish as everyone’s stomachs are full. The fish has been washed down with sparkling wine, with bubbles that make people tired of wishing everyone a good and blessed midsummer, that makes marveling the good weather too effortful. Each time they celebrate the nightless night by raising their glasses, the edges around their words become softer, blurrier.

Later Amma sits in the outhouse – using an actual toilet during midsummer would feel traitorous – and stares at the wet splotch in front of her. The bubbles of more glasses than she could count had reminded of themselves first in the pit of her stomach, then at the tip of her throat and now there they were: the wine and the festive food, on the floor, side by side.

She touches her forehead, cheeks, the lobes of her ears and can’t help but wonder why it always has to be like this. Why is a holiday so near and dear to Nordic hearts darkened by alcohol, always consumed without thought? Each year it takes barely any time until the slurred words and uncomfortable moments of confusion and collusion between family members enter.

She touches her forehead, cheeks, the lobes of her ears and can’t help but wonder why it always has to be like this. Why is a holiday so near and dear to Nordic hearts darkened by alcohol, always consumed without thought?

These are followed by the most idiotic idea of all, swimming under influence. And somewhere this idea ends up with arms flailing in the waves and people waving back with jolly summer spirits, failing to understand the final movements of a drowning man. Their last breath marks the moment they turn from a person to a news headline, a part of a statistic.

Amma’s nausea conjures up a memory, equally amusing as it is humiliating. The force of this memory itself makes her rub her temples and close her eyes tightly, as if this could stop the embarrassing recollection of her first sexual encounter. The shame attached is aged and has grown stronger through the years, contrary to what her friends promised.

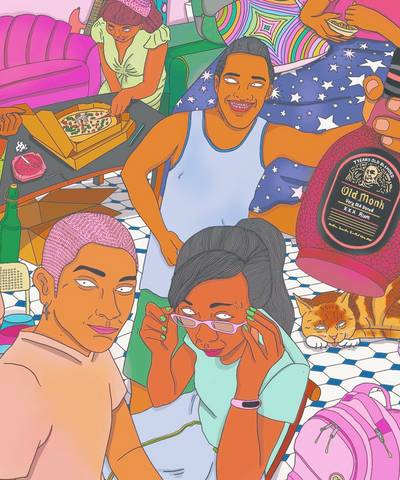

Freshman year, a houseparty, a strong buzz and light feelings of affection towards that one person. What a cliché. Amma opened the zipper of the boy’s jeans with alcohol-induced confidence. The boy – was his name Martin? – was eager to get things started with Amma, yet when Maybe-Martin’s manhood was finally out in the open, so were the contents of Amma’s stomach: four gin and tonics, three shots of Jägermeister and half a beer.

On this night, graced with the view of Maybe-Martin’s vomit covered genitalia, Amma first realized that she was absolutely not built for a straight relationship, or anything straight whatsoever. On the night bus that took her home and away from her mortification, she further pondered on how she had, in fact, never been attracted to boys or men. Not really. She had rather been keen of the mere concept of being attracted to someone, and everyone said that it should be boys. It was only now that she realised it was possible to choose something else, to stray from the straight path, so to say. This wordplay had made her snicker to herself and it cut through the steady humming of the otherwise silent bus.

The bile-scented memory combined with the actual presence of bile become too much for Amma. The door of the outhouse flies open. Nature is greeting her on the other side. Crisp air, no night – no darkness or lightness, warmth or cold. Everything just is as the world is standing still, apart from the gentle waves licking the legs of the dock and a few lonely mosquitoes trying to find their way home.

On the night bus that took her home and away from her mortification, she further pondered on how she had, in fact, never been attracted to boys or men. Not really.

“Amma! You promised to do some midsummer spells with me!” Amma’s little sister runs from the forest, her soft palm gripping wild flowers. She runs blissfully unaware of the gross splotch in the outhouse; of the dark, nationwide alcoholism; of the conundrum of human sexuality. Instead she presents her flowers: a variety of species and sizes, the moldy roots still hanging along. “You have to put seven different flowers under your pillow, so you’ll dream of your future husband!”

Amma hums lovingly to her sister and admires her collection. It’s not a husband she desires, but she wants to play along. “That’s great, Maya. Mom is always asking when I’ll finally bring home a nice man. Maybe now I’ll get her some answers.”

White bunches of cow parsley, yellow buttercups that leave stains, lilac lupines and light blue forget-me-nots. They all go into the same bouquet, with red clovers and the most beautiful daisies. Finally Amma snaps an unfamiliar flower. It’s alright, maybe this will fix the spell. I myself feel so unfamiliar tonight, she thinks, and runs towards the center of the meadow.