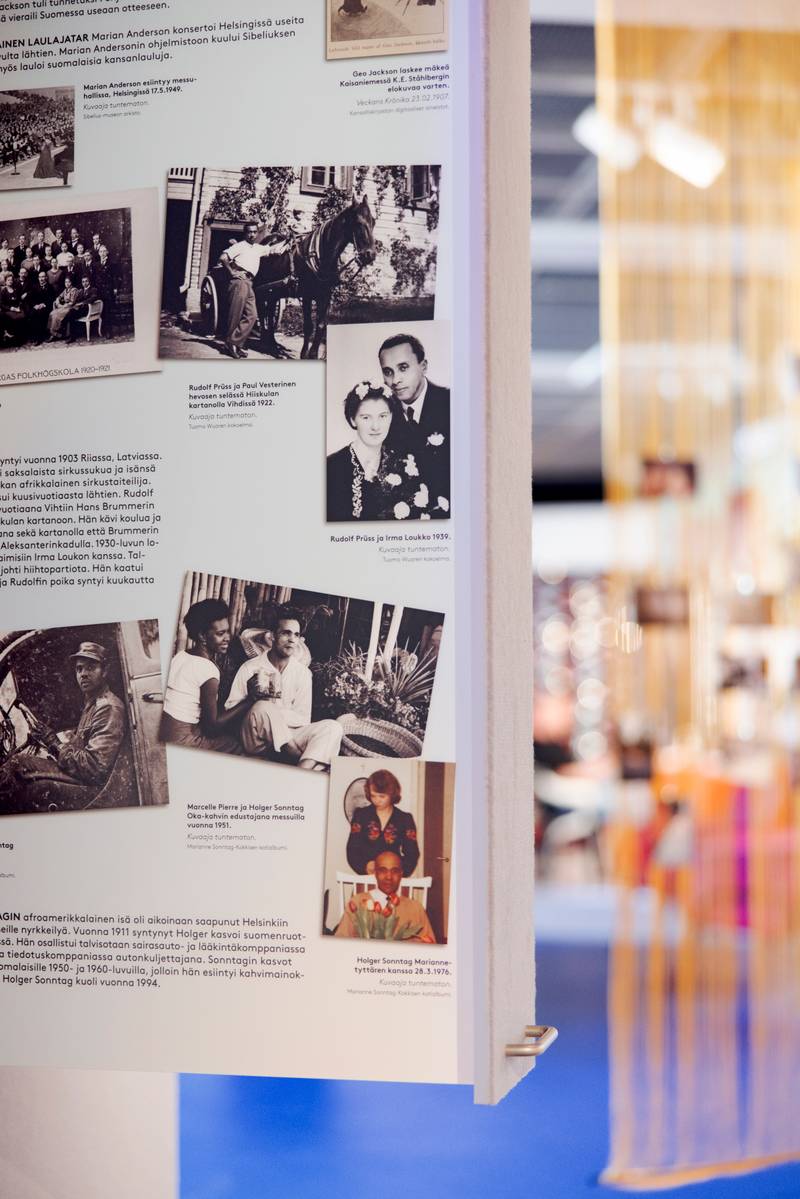

Installation view from the exhibition ‘Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences’ | Photo: Maija Astikainen / Helsinki City Museum, 2023

Shadia Rask (b. 1987, Espoo, Finland) is a PhD and free writer. As a scholar, her research has focused on immigration related health inequity and the manifestations of structural racism. Shadia writes a regular column for Yle and has published an autobiographic essay, ‘Hair play’, on growing up with black curly hair in one of the whitest countries in the world.

Wisam Elfadl is a cultural producer, Queer activist, Wasla collective member, and curator of the ‘Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences’ exhibition at the Helsinki City Museum.

We are two women of color in one of the whitest countries in the world, and we have met to have a conversation about the collective experience of being Afro Finnish and the process and power of seeing this experience at the Helsinki City Museum. It feels fitting and moving to have this conversation in this setting on a sunny May morning in Helsinki: I met Wisam for the first time in Helsinki more than thirty years ago. We have grown, and so has the Afro Finnish community. Yet awareness of Afro Finnish culture and Afro Finns as a part of Helsinki and the Helsinki identity has still been marginal. The purpose of the ‘Being Black’ exhibition is to change this.

SHADIA: This is the first time Afro Finnishness has been presented at this scale in Helsinki. How did the exhibition come into being, Wisam?

WISAM: The exhibition was preceded by two projects. The project ‘Afro Finns in Helsinki’ started off by defining Afro Finnishness, looking at how a Helsinki identity, as in the experience of being from Helsinki, is visible in Afro Finnishness and how Helsinki is influenced by Afro Finnish culture. In another project, we focused on cultural environments, spaces, and feelings of safety and how different population groups use and feel welcome in different public spaces in Helsinki. As a follow-up to these projects, I offered the idea of further exploring Afro Finns’ experiences to the Helsinki City Museum as a grant proposal.

The exhibition was created on a very tight schedule. I started working on this project in August 2022, and the exhibition opened in April 2023. Everything had to be done in eight months: conceptualization, workshops, putting everything together, and finalising them. For the museum, this is a normal timeframe, but for an inclusive, participatory approach, this is very demanding. We needed to build trust and find a community to work with, and all this takes time. And it did take time! It wasn’t until December that we had a key group of 30 people. This was a surprise for the institution, but it’s really no surprise that there is a lack of pre-existing trust and relationships between minorities and institutions like the museum. As the curator, I had to bridge that gap, sail and negotiate between the community and the institution, and steer the whole ship.

But not everyone who has roots in Sub-Saharan Africa and who belongs to the African diaspora identifies as “Afro-Finnish”, instead, some identify, for example, as Black. And the name of the exhibition includes this, too, as it is “Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences”. The exhibition highlights that there is no singular correct way to be Afro-Finnish, and Black people with African origins living in Finland do not have one common identity, history or culture.

The exhibition is about Afro Finns’ experiences, with the term Afro Finnish referring to Finns who have roots in Sub-Saharan Africa and who belong to the African diaspora in a wider sense. The typical racist narrative is that Africanness and Finnishness cancel each other out. One cannot be both, only either or. Your work in the Wasla collective has also been at the intersection of identities, being Queer and Muslim. How do you see your work at the supposedly impossible intersection of these identities?

It’s revolutionary that the words ‘Afro Finn’1 exist side by side in the name of the exhibition. In the Finnish written form, “afrosuomalainen” in one word, without any hyphen or gap in between. In a way, the use of this term is a formal recognition by a Finnish institution that we exist. This identity wasn’t available for us to claim in the past. Afro-Finnish is a new term that has come into being and is being used in our community, starting in 2017 in the events and communication of Ruskeat Tytöt and Good Hair Day.2

But not everyone who has roots in Sub-Saharan Africa and who belongs to the African diaspora identifies as “Afro-Finnish”, instead, some identify, for example, as Black. And the name of the exhibition includes this, too, as it is “Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences”. The exhibition highlights that there is no singular correct way to be Afro-Finnish, and Black people with African origins living in Finland do not have one common identity, history or culture.

There are definitely similarities between the process of curating the exhibition and the work I have done in the Wasla collective. Firstly, starting with recognising that we exist as a community, and then moving on to reach out and gather that community together for action. Securing a grant and resources for community work has been significant in both cases. It’s easier for people to commit to projects with a clear timeframe and goal instead of just meeting regularly as a community.

Instead of pigeonholing, I am hoping that the term Afro Finnish can be a protective shield that we can use against the too curious question of “Where are you really from?”. You can say you are Afro Finnish without revealing anything personal about yourself. You don’t have to share that you are adopted from this or that country or how your parents met or came to Finland. I want to teach the next generation that you don’t have to let go of your boundaries and right to privacy. You don’t need to explain yourself.

People don’t know how much of Helsinki’s art and culture scene is significantly influenced and run by Afro Finns. Our role and work have been invisible to the general public. But it’s true that this sort of elite side of Afro Finnishness is only one side. And for the sake of our community, it would be important to open other sides as well.

For me, the exhibition felt like a powerful testimony that we not only exist but also excel and succeed in Finnish society. We have gained positions of power and recognition visible in our professional titles, like in the interviews of Nosh A. Lody, Creative Director, and Melina Korvenkontio, CEO. Such representation and role models are empowering. At the same time, I grieve the experience that, as a person of color, unless you are excellent, you don’t have the right to exist in Finnish society.

What are your thoughts on this tension and balance between the importance of representation and role models and the burden of having to excel to have the right to exist?

I recognize this. And there is a specific class that is visible in the exhibition. It’s the specific urban “Helsinki cream” that is successful in the scene. It is important to understand that the Afro Finnish culture portrayed in the exhibition is pierced by class. It’s us Afro Finns who have become middle class and successful. In that sense, it’s a homogenous portrayal of Afro Finnishness. But if we think about the preconceptions that white Finns have of Africans, it is that we are not middle class and successful.

That Afro Finnishness is and can be shown as it is in the exhibition; it’s my way of showing my middle finger to those who claim that “you came in the 90s and you all live in one spot, that you’re all uneducated and don’t speak Finnish, that you have fucked up your lives and ruin everything.”

People don’t know how much of Helsinki’s art and culture scene is significantly influenced and run by Afro Finns. Our role and work have been invisible to the general public. But it’s true that this sort of elite side of Afro Finnishness is only one side. And for the sake of our community, it would be important to open other sides as well.

But the exhibition, as it is, is so important if we think about our children and youth who visit the museum. Usually, they just visit the Children’s Town. But now, with the ‘Being Black’ exhibition, they are exploring the whole house and seeing Afro Finns as a part of Helsinki. And that is what we aspired to do.

This history of minorities is often overshadowed by the history of the majority. This makes it seem as if minorities never existed or were just a few exceptions. Rosa Emilia Clay is often portrayed as the first African Finnish person, but the exhibition diversifies this single story. How did you manage to uncover and rewrite a fuller picture of Afro Finnish history?

When I began this work, historical information on Afro Finns was literally hidden. This experience of missing information and having to search for and pull out information is actually physically portrayed in the exhibition. In the middle of the exhibition room, there is a gray totem, out of which the visitors have to pull out historical facts and findings.

When going through the archives, I was prepared to find at most ten people in addition to Rosa. I couldn’t believe I needed to summarize and make choices because we found so many. And these people, Afro Finns from history, challenge the common stereotype of Africans coming to Finland only because of war or crisis or some strange coincidence. We found scores of professionals: intellectuals, musicians, athletes, etc. I found comfort in realising that Rosa was not the only one. I want to believe that as she walked the streets in Kuopio at the end of the 1800s, there may have been other Black people, too. And they may have exchanged solidarity nods. It would be fantastic if someone would dream up and screenwrite this history of Afro Finnishness, the brown cream, and vivid urban life in the 1800s. What if the urban and elite Afro Finnishness that we see today is something that also existed then?

It’s funny to think that the past can also be futuristic in the sense that you have to dream it into being. Imagine what it could have been like. It’s not traditional sci-fi but Afrofuturism that is situated in the past. And the past can be as absurd and “ufo” to think about and imagine as the future.

Installation views from the exhibition ‘Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences’ | Photo: Maija Astikainen / Helsinki City Museum, 2023

In the exhibition, visitors are challenged to ask who has the right to write whose history. What are your thoughts on the power and privilege of museums? If I think of myself as a researcher, an Afro Finnish migration scholar, I have often felt like an ‘outsider within’. I have expertise and am part of the institution, but at the same time, I have experiential knowledge and am often the only one in the room. Does this resonate with your experience of curating the exhibition?

I feel that the Afro Finnish community has not been fully aware of the power of museums. Museums are widely visited, and therefore exhibition themes and content have significant power and potential to influence societal norms and narratives. When the Afro Finnish community raises the importance of increasing representation in society, representation is typically addressed in publishing, media and education but rarely in the museum context. We have been asking critical questions about who’s a journalist, who’s in front of and behind cameras, who’s teaching our kids, is there diversity in school books. But the museum as a space for learning has been entirely outside of this discussion of representation. Even though the museum is a place our children and youth regularly visit through school.

As community members and activists, we need to know how to work the system and how to turn our work into projects. In the case of this exhibition, I came to the museum with the confrontation that there is nothing about us Afro Finns in the museum, and we have the right to exist here. You have a gap, and I have an idea. Different institutions are dependent on our knowing how to come to them with our ideas. At the same time, you must be critically aware not to objectify, expose or burden yourself and your community too much. You need to make sure that the deal is fair.

The question of who has the right and skills to write the history of minorities is essential. Most museums have a fairly limited history of community-based, inclusive, and participatory work, which is one reason there is a lack of trust and commitment between minorities and museums. When preparing the exhibition, I had to act as a spokesperson for the museum, build trust, and negotiate between the community and the museum. During the most intensive weeks, I worked round the clock – regular office hours with paperwork from 8 am to 4 pm and community work and workshops from 5 to 8 pm. I have had to be clear about which hat I wear when speaking from my position as a professional and curator and acting as a community member. In that sense, there is a double role of being an outsider within.

The key themes of the exhibition are family and friendships, ideals of beauty, identity, and activism. Were there themes that surprised you or that you chose to leave outside the exhibition themes?

Everything is tied down to resilience and activism – fighting and surviving racism. But the most challenging theme in the workshops, and one that we couldn’t dive into deeply because it would have required after-care and counseling opportunities after the workshops, was the diaspora experience. The awareness and longing for family members who are far away, the feeling of being torn between different locations, and the awareness of having a family that is present and part of a reality other than that visible here in Finland. Part of the diaspora experience is also the grief that I don’t know the language and cannot keep in contact. It was even difficult to capture the diaspora experience and pain. Meaningful personal objects included photographs of aunts and uncles and pieces of fabric brought and sown into festive clothes here in Finland. With some of these objects, we consciously chose not to open their meaning with text in the exhibition to allow for privacy and the intimate nature of our experiences.

With some other objects, private experiences turned out to be collective ones – for example, the c-cassette. Many of us had thought that recording and sending c-cassettes as a form of keeping contact with relatives was something unique to our individual families, but it turned out that this was a shared practice. And the c-cassette as an object also captures the nostalgia of our parents’ generation.

The intergenerational diaspora experience is one of the themes not fully explored in the exhibition. I am uncertain if our parents’ generation is willing to open up those wounds and hurts. They played into the racist system to survive. I hope the museum understands many themes and layers of Afro Finns’ experiences are still missing. I fear that Afro Finnishness is seen only as a part of Helsinki and the Helsinki identity, or the capital city region, but not as part of Finland. It’s not like Afro Finnishness has now been covered, and that’s that.

And backlash – yes, there has been a backlash. We have had to plan what to do with racist remarks that visitors have written on the exhibition wall. As the exhibition curator, I was asked what should we do with those remarks—should we throw them away? I said no, we will not throw them away; we will leave them on display but grouped together. Those remarks, racism, are part of the everyday experience of being Afro Finnish. We don’t want to erase that.

Before we finish, I want to ask you, how has the museum prepared for backlash? And what progress has the exhibition brought forth and is a part of?

I definitely see progress in society as a whole. We have two Afro Finnish women as Parliament members at Arkadianmäki, which is revolutionary. And at the same time, the rhetoric and political atmosphere in Finland is what it is.

The significance of the exhibition is not just what you see on the fourth floor of the Helsinki City Museum. The exhibition has also sparked spin-off events held at the museum, like a fashion show and Good Hair Day events. Most importantly, antiracism training and safer space guidelines have been crucial tools in creating and opening an exhibition like this. Together with the museum, we have had to rethink how we welcome and include new groups of visitors.

And backlash – yes, there has been a backlash. We have had to plan what to do with racist remarks that visitors have written on the exhibition wall. As the exhibition curator, I was asked what should we do with those remarks—should we throw them away? I said no, we will not throw them away; we will leave them on display but grouped together. Those remarks, racism, are part of the everyday experience of being Afro Finnish. We don’t want to erase that. But it’s also not the only experience.

My hope is that the exhibition can strengthen our community. The workshops really revealed the fatigue and sense of isolation people have experienced since the spring of 2020, with George Floyd’s killing by the police and the pandemic. The exhibition and the upcoming workshops can be the location and the space to experience that you are not alone.

For newcomers and Afro Finns still looking for their community, ‘Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences’ is full of clues and cues to where they can find people and places to belong.

Installation views from the exhibition ‘Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences’ | Photo: Maija Astikainen / Helsinki City Museum, 2023

The exhibition ‘Being Black – Afro Finns’ Experiences’ offers an overview of the present and past of Helsinki as experienced and told by Afro Finns. Helsinki City Museum, Aleksanterinkatu 16, until September 24, 2023. Free entry.