Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

To forgive our aunties and their misguided yet well-meant advice

Elham Rahmati

Last month, I visited a second-hand bookstore somewhere in Punavuori. I was looking for a book to buy as a gift for someone but couldn’t find anything. The books in English were few, mostly classics and not in a good shape. Somehow on a top-shelf, I came across a book in a tip-top condition called Mister Pip1 written by Lloyd Jones; I didn’t know the novel or the author but the book had a beautifully illustrated hardcover and sometimes, it is reason enough to purchase a book just because it’s pretty. So for now I’m keeping it for myself and will not offer it as a gift to anyone unless later it turns out the inside doesn’t measure up to the outside, in that case, I might just revisit my generosity.

Mister Pip opens on a remote South Pacific island, threatened by uprising, where young Matilda and her classmates find their lives surprisingly intertwined with those of a boy called Pip, the hero of Mr Dickens’s The Great Expectations. The book is introduced to the kids through a man popularly known as Pop Eye who is the only teacher left on the conflict-stricken island. He confesses on the first day of school that he is not a teacher and that apart from his love of The Great Expectations he doesn’t have much to offer. So as a solution he invites the family members of the students to each come to the class and share a piece of their knowledge, tools they have gathered throughout their life to understand and enjoy their surroundings and to survive. They can talk about anything, about their love for the colour blue or learning to predict the weather by looking at the behaviour of crabs: “Wind and rain are on the way if a crab digs straight down and blocks the hole with sand leaving marks like sun rays. We can expect strong winds but no rain if a crab leaves behind a pile of sand but does not cover the hole.” I haven’t finished the book yet, and to be honest, I do find the general theme of a novel by a dead white man being the source of joy in a colonized island inhabited by Black people, quite problematic. But the glorification of cultural imperialism aside, I found the chapters about the ordinary people giving tips and advice and sharing their acquired knowledge on the ordinary things as part of a school curriculum interesting.

I thought about what I would teach if I was given an hour to share the quintessence of all that I know, what advice would I give? Not on a remote island in the South Pacifics, but here in the contemporary art scene of a small Nordic European country.

I majored in film studies in high school. I was and still am extremely passionate about cinema and my teenage dream was to become a film director. To be specific, I wanted to be the second coming of Martin Scorsese. However, being too shy, introverted and not being very good at standing up for myself in group projects didn’t make things easy. When I got my diploma and had to figure out a university plan, I went to one of my younger aunts for advice. She told me, “it doesn’t matter how talented you are, how much you try, how much you read, how many films you watch and how many exceptional scripts you write. You can never become a film director because you don’t have the personality it requires and you can’t acquire those necessary traits by studying and practicing”. So I moved on to get a BA in painting as all it asked for was me, my introverted personality, canvas, paint and brush.

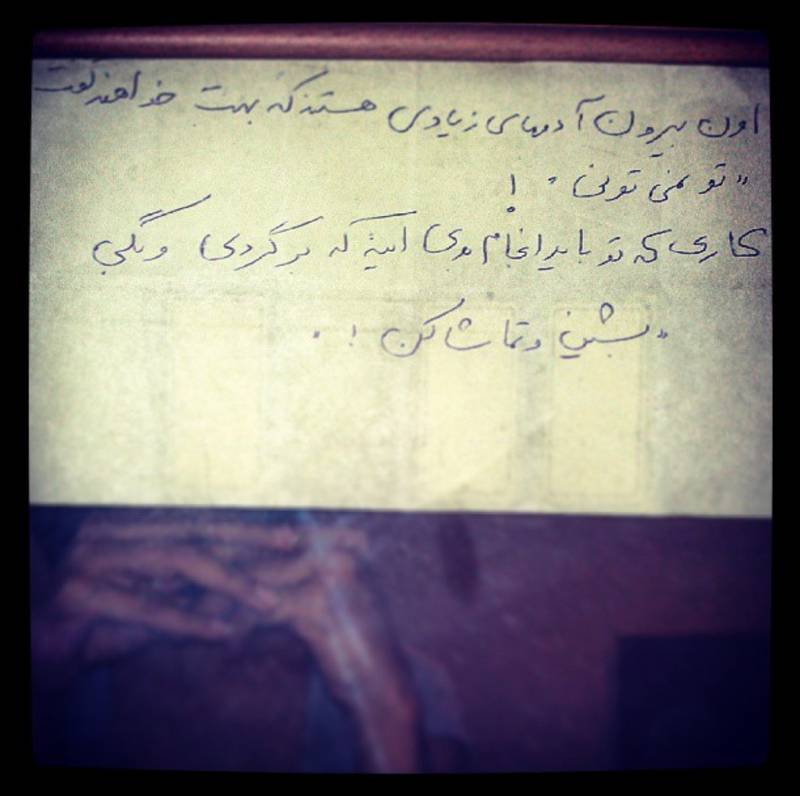

Screenshot of a 2013 Instagram post I made of the note on the mirror. The note says, “Out there, you are going to face many who will tell you that “You Can’t”, what you need to do is to turn to them and tell them, “just sit back and watch me!”

The note said, “Out there, you are going to face many who will tell you that “You Can’t”, what you need to do is to turn to them and tell them, “just sit back and watch me!”

A few days before I left Iran to move to Italy in 2013, I found a note from my mother attached to the mirror in my room. The note said, “Out there, you are going to face many who will tell you that “You Can’t”, what you need to do is to turn to them and tell them, “just sit back and watch me!”. I took two things to heart from this note; the encouragement I needed to become a self-righteous bitch who takes joy in proving everyone wrong, and more importantly, the note was emblematic of my mother’s extraordinary level of care and strength. She was worried and scared to send her only daughter to Europe alone. At the time, I was the only person in my family to ever move abroad, before me there were my mother’s cousins who left Iran before the 1979 revolution. One got mysteriously killed in the US, the other one mysteriously disappeared in Germany. I know so many parents who would use all their power to stop their children, especially their daughters from leaving, but no, not her. All she did was to give badass advice that I tend to revisit a lot, as many times that I have been made to feel invisible, irrelevant, unheard, incapable or weak. As many times as I have been told, “you can’t”.

A few months ago, a friend called me to ask if I could read their grant application. Reviewing grant applications is something I gladly do for anyone that asks because I somehow feel like I’ve gotten the hang of things and I can offer solid advice here and there. This particular application though left me speechless, it was extremely ambitious and beyond the means of that person to be able to undertake at such an early stage in their career. To realize it, they’d have to pull in millions of Euros and that just didn’t seem realistic to me. So I gathered my courage and all the tact I had at my disposal to tell them that “hey, you gotta start smaller, be consistent in your work, build a relevant CV, don’t jump from one genre to another, tone your literature down, make it easily digestible, imagine how you and your application comes across through the eyes of a jury member who is bored, impatient and hard to please, etc.” Basically, all the things I had been told by someone from the Kone Foundation who had been invited as a guest lecturer to the ‘Artist in Society’ course in our MA programme ViCCA. The general outcome of the course was to prepare us art students for the tough and uncaring post-graduation world that expects us. And boy, did she do a great job at that. At one point she told us “imagine yourselves as products, you have to learn to sell yourselves to us”. I’m paraphrasing, of course, but that was the gist she was there to impart. And although I despised the attitude and everything around it, I accepted it as a rule and not only accepted it, I now remind others of it. After fully deflating my friend with my so-called realistic and pragmatic advice, I hung up the phone and immediately felt like utter shit. I felt like I had just spent an hour on the phone telling someone “you can’t”. When had I turned into what my mother had warned me against? When had I turned into my aunt?

I want my friends to be idealistic and ambitious when it comes to their artistic practice, I believe they indeed CAN do anything, but since we’re not living in an American dream-success story-trash Hollywood movie, chances are that our brilliant ideas will not get recognition in short term and therefore things will not always work out as we’d like them, especially if we are not white and upper-class.

I wanted to call back and apologize and tell my friend that, “hey fuck everything and everyone, if you want to work on a million euro idea, a year into graduation from art school, then you do that and while you’re at it tell others to fuck off and watch you”. I thought about doing that for a while and how happy it would make me to be that person, but then, in the end, I didn’t do it. It didn’t feel like a responsible thing to do. I want my friends to be idealistic and ambitious when it comes to their artistic practice, I believe they indeed CAN do anything, but since we’re not living in an American dream-success story-trash Hollywood movie, chances are that our brilliant ideas will not get recognition in short term and therefore things will not always work out as we’d like them, especially if we are not white and upper-class, which is why I advise friends: “hey, you gotta start smaller, be consistent in your work, build a relevant CV, don’t jump from one genre to another, tone your literature down, make it easily digestible, imagine how you and your application comes across through the eyes of a jury member who is bored, impatient and hard to please, etc.” I suppose I CAN learn to deal with the self-loathing that this uninspiring advice brings upon me because I’m not telling anyone, “you can’t”.

Giving out tips and advice is all about what you know at the time, what has and has not worked for you until then. After that, we are free to go to the beach and learn about the behaviour of the crabs on our own, all we’ve been granted is a nudge.

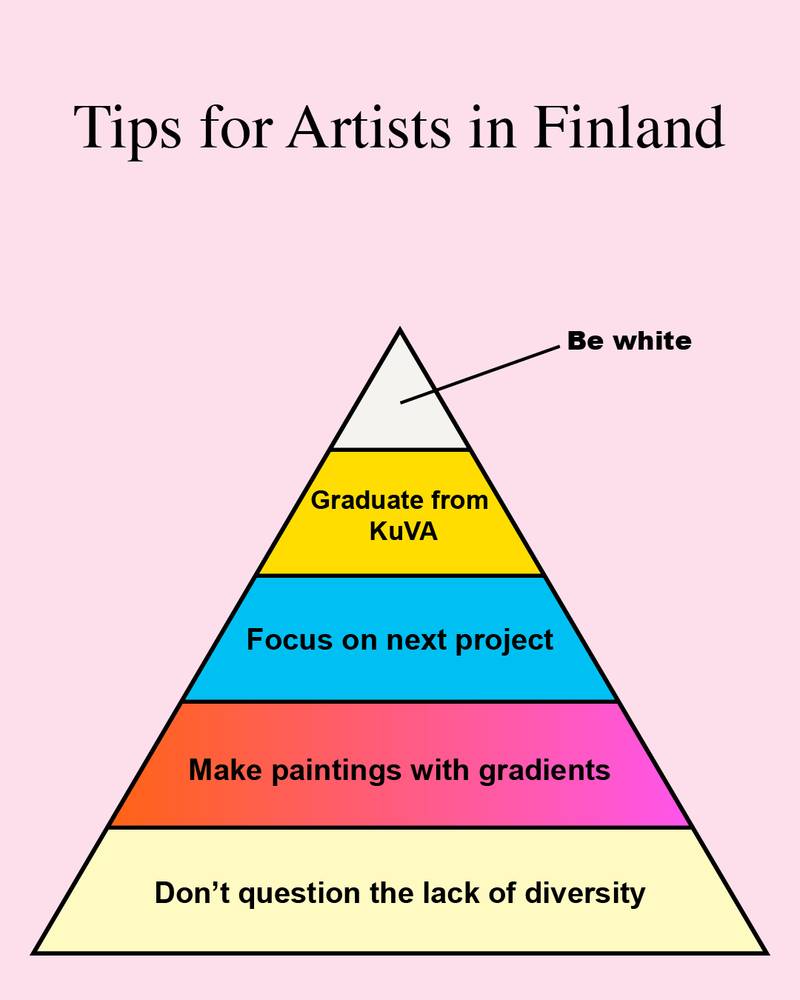

Vidha Saumya, Tips for Artists in Finland, 2021

The ASAP of soft and diversity

Vidha Saumya

If you are a woman of colour who speaks her mind, there is a good possibility that you receive email invitations to diversify panels – two birds with one stone. These invitations are rushed, presumptuous and under-researched – the tone compelling, to be answered ASAP with a positive affirmation. There is no time to ask questions or find who your co-panelists are or enquire what the underlying politics of their context is. You quickly scan the invitation again to see if they mention a remuneration somewhere. Swifter than a pastry chef brushing raspberry coulis on a dessert plate, a quick email follows, ‘And, there is a fee’ – as an afterthought, lest you think, I’m not doing this labour for free – this they know. They answer all your questions sprinkled with more microaggressions than microgreens in a takeaway salad. Fuming in tragic laughter at their audacity, you wonder how these ‘professionals’ sending you improvised invitations even got that job. Now, what all can you indulge in, so, you say ya, why not and move on – at least I get a chance to speak. Opportunities in the arts are few and far between for people of colour and at the moment you cannot afford to say no. In these groups, you meet colleagues, often reputable white male curators and directors who rub it into your face about their 100 years of experience and the 50th renewal of their contract because without them the organization would be an inconceivable mess. If you survive this bluster, keep your sarcastic fangs to yourself, focus on the work at hand, and find joy in it, you anoint yourself as the well-behaved willing kind. As a reward, you may get cherry-picked to perform duties over somebody who is better deserving. You know this truth but you remain silent because you need the job and sometimes you need the validation. This validation is not easy to get either. When you do your job well, it was expected of you, when you fail, you were expected to. Even after you macerate your straightforwardness and bite, the work scene becomes a relapsing rash because time after time your grasp on matters, shrouded under constructive criticism and teamwork, is casually dismissed. Sooner or later, the voice in your speech becomes watchful and you tread softly to avoid stirring the one-culture pot. With a thawing sharpness, you become that token brown person who is professional and diligent, accepting and forgiving.

If you are a woman of colour who speaks her mind and you are hired to create diversity means that there exists no diversity and hence you are proffered the job to be absolutely correct and refurbish the institution’s facade. Without diversity, institutions wouldn’t be woke – this also they know. Even so, ‘diversity’ is still extra luggage. It is heavy and institutions don’t know what to do with it. So diversity is addressed in panels, themes of exhibitions and selection FAQs. Sometimes artists, projects, stage festivals and seminars are funded – a vibrant liberal facade – nothing genuine. Even if you’re not a token recruit, you as the outsourced fixed-term employee, become a secure and fast alternative to actually hiring someone full time for doing the work or revising hiring and working policies from the inside out. To offer the best rate of return, you invest your time mining the treasures of brown wisdom which you have, or must (and they) assume you have. But how can one person have so much wisdom? It is not possible, you are bound to fail.

Without diversity, institutions wouldn’t be woke – this they know also. Even so, ‘diversity’ is still extra luggage. It is heavy and institutions don’t know what to do with it.

Even though in Finland, there is a growing trend to scream F A I L U R E as ecstatically as EUREKA, but if you are a woman of colour who speaks her mind your failure is stigmatized. If you fail, your mess is not theirs to clean and it shows up as a watermark on the CV of others like you. That ‘all brown people are the same’, is a manifestation of institutions’ lack of common sense, arrogance and patronizing attitude. But the innermost obstacles to a genuine discussion on diversity are the anti-establishment industry (AEI) faking their way into diversity and making a good show of it, too. AEI are the ones you don’t want to offend, they are the ones who display indifference. If they like a brown person, they like the agreeable side of them. This experience is troubling because it allows no real discussion, no confrontation, no serious questions. It is a system set up to fail. And when you do (fail), the multiculti institutions doing diversity work blithely attest, let’s just hire from within our circles.

It is at these sites that I first heard the word ‘soft’ – a constant drone. Unlike the seasonal cream and sugar bursting laskiaispulla that leave bakery windows as February ends – the murmuring of ‘soft’ stays around. Like the kahvi available from kiosks to cafes, it comes across as being omnipresent. I try very hard to like it, and I can’t.

I would like to think that ‘soft’ as a stand-in for relationality, emotionality, vulnerability, and kindness is fundamental to the constitution of art and academia. So what’s the problem with its overuse, why does it feel abrasive?

But as a person of colour when you enter these spaces, beyond its emotional register, ‘soft’ strikes like a lightning bolt. It surveils and polices, it mocks and others. It becomes a code of conduct of which no one told you the rules.

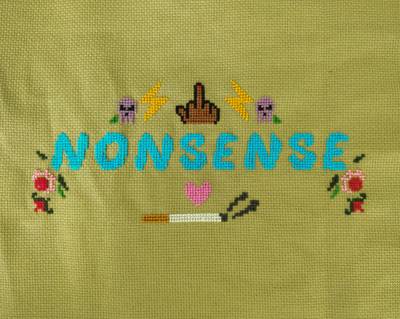

It bruises because as a term, that can help expand and diversify the inclusiveness of aesthetics and discursive contents, it is becoming increasingly inaccessible and mostly white. And it’s not like I feel like a victim to this order. I feel strong – I am a migrant, a woman, a successful grantee, I can deal with those that resist my presence – I cross-stitch, I write poems and I know more than three languages. But as a person of colour when you enter these spaces, beyond its emotional register, ‘soft’ strikes like a lightning bolt. It surveils and polices, it mocks and others. It becomes a code of conduct of which no one told you the rules. For those with privileges and higher ranking in the hegemonic order of the world, soft is a layer of comfort, ease, and dare I say, laziness. I am not against laziness or for that matter, softness; as a woman of colour living in a patriarchal, capitalist, imperialist society – sometimes I can only rebel with laziness and seek pleasure in it. But how should I cope when ‘soft’ is not extended towards me?

I am a woman of colour in the white environs of Finland and I am spiralling in confusion and amusement at my relationship with the omnipresent ‘soft’ and the ubiquitous ‘diversity’. Is there a way to avoid soft and diversity from becoming another appropriated neoliberal idea of satisfaction and wokeness? Can they instead form a space of listening, preparing, and allowing the benefit of time?