Visitors at the Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit 14 ‘Long-distance Friendships’ curated by Inga Lāce and Alicia Knock, in Riga, September 2023. Photo: Andrejs Strokins

Santa Hirša works as an independent art historian and critic based in Riga, Latvia, and has received ‘Normunds Naumanis Award in Art Criticism (2021)’. She is the author of monographs about artists Krišs Salmanis (2018) and Andris Breže (2020), editor of multiple publications and collections of articles. Her research focuses on late socialist and postsocialist visual art and contemporary art processes.

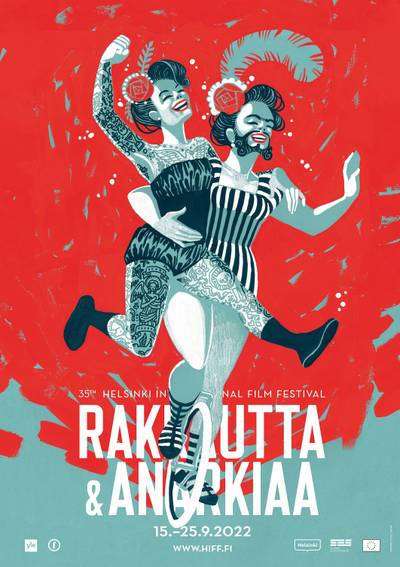

Survival Kit, the 14th edition of the contemporary art festival organised by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA), took place from September 7 to October 8, 2023, at Vidzeme Market in Riga. Each year, the festival focuses on socially charged themes and offers “survival” strategies for different modern complexities in the form of an exhibition and accompanying programme. This edition featured two exhibitions – the festival’s central exhibition, ‘Long-distance Friendships,’ curated by Inga Lāce and Alicia Knock, and the final exhibition of the project The Artist is Present. It is significant to keep in mind that LCCA is the only visual art institution in Latvia that consistently works with socially and politically oriented issues in the otherwise generally conservative local environment. With different projects, LCCA seeks to reduce prejudices and provide a broader perspective on the layers of social and political reality.

Both the general and the art communities in Latvia can be described as being fairly closed off to uncomfortable questions and even to the role of art in addressing ideologically and politically charged issues. For these reasons alone, Survival Kit must be considered not just another glamour art event but an event that seeks to radically redefine the role of art in the local cultural space. The festival involves local and international artists and curators every year, acting as an important medium between the international and Latvian art scenes.

As the title ‘Long-Distance Friendships’ suggests, this year, Survival Kit 14 focuses on parted relationships, using the metaphor of distance to denote both geographical and mental remoteness. At the same time, the notion of friendships serves as a signifier for broader, contradictory, and ideologically saturated patterns of intercultural relations. The exhibition focuses on cultural links and microhistories between Eastern European and African countries, with parallel satellite exhibitions at the Kaunas Biennial, Lithuania, and the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts, Slovenia. The event’s occurrence in several parallel countries is in line with the values of ‘long-distance friendships” and the need for new and unusual forms of collaboration, including the state of migration. Despite this egalitarian premise, it is unclear what the considerations were behind the choice of these particular events and whether anyone other than the organisers could attend all the exhibitions and fully comprehend the message of Survival Kit 14. What are the guiding principles, ethics, and practicalities of producing a programme that is not fully viewable and accessible to the viewers? And what considerations and conditions have underpinned these specific institutional friendships? How and why do art festivals ‘befriend’ each other nowadays? Are these friendships based on financial considerations? Although networking and collaborations are a normal, common practice in contemporary art, it seems that their intentions are more often based on creating the broadest possible programme, i.e., to focus on the quantitative aspects without reflecting deeper connections between institutional organisms in the content. Often, these collaborations become merely an institutional appendix, which, in this case, does not seem to be viewer-friendly.

The dramaturgy of the exhibition creates a narrative out of many individual pieces that do not have to illustrate the key theme in a directly literal way, but proportionally, most of the works are not really about ‘stories of resistance, resilience, and transnational solidarity between Africa and Eastern Europe’ as mentioned in the curator’s text. As a result, the exhibition unfolds into a much wider ramification, and a gap is formed between what is claimed in the curatorial statement and what manifests in the artworks and exhibits.

At first glance, the links between Soviet and African cultural diplomacy seem to be a fascinating topic through which to broaden local (as Eastern Europeans) perceptions of different forms of cultural interaction, shed light on lesser-known pages of Eastern European history, dispel racist prejudices, and see the seemingly “other” as an essential part of our common experience. Historically, one of the main tools of these alliances was scholarships granted by the Soviet Union for non-European students to study in the USSR or Eastern Bloc countries.1 The exhibition explores the life stories of these students, their relations with the Soviet people and their own culture, as well as complex cultural identities under given historical circumstances. Through various everyday objects and everyday material culture, Survival Kit 14 seeks to grasp the more personal stories and experiences behind these ideological mechanisms. The attraction of students under the guise of “anti-colonialism” implemented the Soviet policy of imperialism and, in that sense, gives the notion of friendship present in the exhibit’s title an ironic load. Curators Inga Lāce and Alicia Knock offer the viewer a landslide of information in artistic and documentary forms. So, like an archaeologist, the viewer has to dive into it by themselves because the overall message from the curators does not seem to be aligned. The cultural and historical layers of the exhibition are very dense and diverse. Unfortunately, the viewer is left alone in front of it, having to piece the story together.

Exhibition works that address the history of Latvia and Riga focus on the Riga Civil Aviation Engineers Institute, which, since the 1960s, has provided special scholarships for international students from non-European, mostly African countries. Riga-born artist Inga Erdmane is more directly concerned with this topic. For her work Imprints, she has searched for and interviewed former students who received this scholarship, exploring the relationship between their personal memories and collective awareness of their presence, which was, quoting the author, ‘so mysterious and mystical that hardly anyone knew anything about them’. Several other works in Survival Kit 14 focus on filmmaking students who travelled to Eastern Europe, bearing in mind the special role of cinema in Soviet ideological education. The project, Why a School? Notes from an Unrealised Film by Johannesburg-based, para-disciplinary artist Nolan Oswald Dennis presents their uncle Nigel Dennis’s script and research notes about his film, which was never realised but was dedicated to the generation of South African teenagers who went into exile to join the armed struggle against Apartheid after student uprisings in 1976. Zbinak Baladran and Tereza Stejskalova, in the video Autoignition and installation Biafra of Spirit, reveal acts of racism and xenophobia that international students were forced to face behind the spirit of state-imposed solidarity with the former colonies. Despite these focused explorations, the exhibition simultaneously gives the impression that it has run out of the ‘material’, so it casts very wide circles around the main theme. Several works fall outside the announced conceptual trajectory, expanding the depth of field on a general critique of colonialism and capitalism. For example, Thierry Oussou’s series of paintings Equilibrium Wind or Liene Pavlovska’s installation on Soviet-era microstrategies of so-called soft resistance pay attention to the Soviet souvenir wood incrustrations as ideologically charged products of their time. Of course, the dramaturgy of the exhibition creates a narrative out of many individual pieces that do not have to illustrate the key theme in a directly literal way, but proportionally, most of the works are not really about ‘stories of resistance, resilience, and transnational solidarity between Africa and Eastern Europe’ as mentioned in the curator’s text. As a result, the exhibition unfolds into a much wider ramification, and a gap is formed between what is claimed in the curatorial statement and what manifests in the artworks and exhibits.

Equilibrium Wind by Thierry Oussou | Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Cut-outs by Liene Pavlovska | Photo: Kristīne Madjare

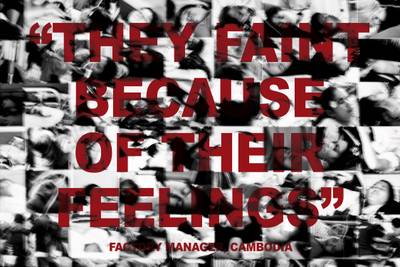

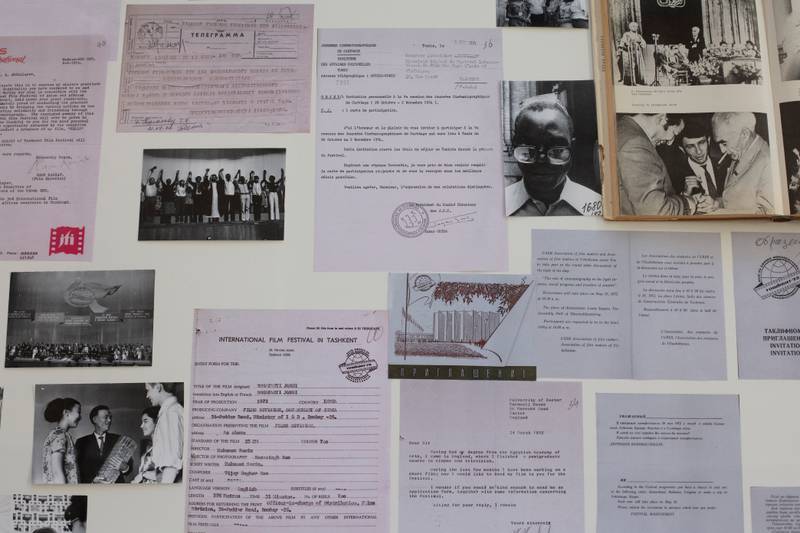

The exhaustive amount of documentary and archival material—mostly a selection of artefacts without a wider context—seems problematic. Not just because it is easier to imagine such objects being exhibited in a local history museum or historical exhibition, but because, as an artistic medium, they do not perform their potential in the exhibition context and are repeated in too many works. Examples include physically literal micro-archives like the ‘DAVRA Collective’ research project that studies the Tashkent International Film Festival and the development of archival impulses in other media such as Ilona Nemeth’s Planetary Composition from Flowers. Exhibiting the archive in the art environment without researching or contextualising it gives the impression of a task that has not been fully accomplished. As a result, artworks presented in the exhibition frequently lose their power of expression, operating mainly at the level of naked, basic facts. Documentary evidence can function as an artistic gesture; this strategy is not denied in contemporary art language. “Documentary mode is a transnational language of practice whose standard narratives are recognized all over the world, and its forms are almost independent of national and cultural difference” (Hito Steyerl, 2008)2. But is it always the case? Is this drive for ever more authentic representation of the real always serving as an innovative form of contemporary art that deconstructs distinctions between art and non-art, fiction and fact, artifice and authenticity, etc.? A moving narration of private memories about the experience and identity of a non-white generation growing up in Latvia in the 1990s exposes phenomena that are interesting on multiple socio-anthropological levels, but does adding visual elements to the narrative automatically make it a work of art? Where is the margin between private narrative and artwork based on personal experience, and is this margin still relevant nowadays?

Friendship of Peoples: Tashkent, Film, Exchange by DAVRA Collective (Valeriya Kim, Dona Kulmatova, Zumrad Mirzalieva and Saodat Ismailova) | Photo: Kristīne Madjare

Planetary Composition from Flowers by Ilona Németh | Photo: Kristīne Madjare

This problem of blurred lines between private and artistic narration can be applied to most of the exhibition, which reads more like an ethno-cultural-historical expedition with visual complements. I’m not advocating for highly formal and visually pleasing art that aestheticizes social facts, but if we consider that art channels information in ways that allow us to read it more sensitively, emotionally, and from new perspectives, it is not unrealistic to expect that the experience of art should create ways of the viewers to approach stories through a more attuned balance between these two (rational and affective) methods and forms of art. “(…) contemporary activist art that is closely connected with corporality and affectivity—and, consequently, with the intersection and problematizing of epistemic and ontological links—is the area in which the most effective decolonial models emerge.” (Madina Tlostanova, 2018)3

The second problematic aspect is the ignorance of the background of contemporary political events in the curatorial framework, which does not remain merely as a backdrop but actively influences how things are seen and understood. The key theme of the exhibition can be described as research of historical Soviet imperialism and its less-known impacts on different cultures, which sadly continues its existence in highly destructive Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, so the question remains open - to which degree this imperialism is still ‘historical’? Invasion is based on the same colonial beliefs of one nation’s superiority over the other. That the curators avoid exploring this “friendship” through the lens of imperialist ideology in the Soviet period and today (including Russia’s close ties with Africa nowadays) is confusing, for it ignores the exhibition’s mandate to highlight contradictions and decolonise understandings of history.

Neutrality in political positions is also reflected in the over-presence of documentaries media in the exhibition - just as things and objects are given the task to “speak for themselves”, the curators do not seem to take active statements or positions regarding contemporary Russia’s imperialism and close ties to contemporary Africa, which seems an unexpected attitude in the context of such significant and loaded topics. Certain aspects of these friendships are particularly problematic, especially in the wartimes. For example, the Riga Institute of Civil Aviation Engineers played an important role in forming the Interfront. This organisation sought to prevent Latvia from regaining its independence in the late 1980s. This aspect is nowhere to be seen in the exhibition, which looks at the stories from only one side, ignoring the locally relevant contexts and the more complex decolonisation processes. The contradictory attitudes of the international non-European students towards the collapse of the Soviet Union are only slightly touched upon in Christopher Ejugbo’s text Prologue, published in the exhibition’s catalogue. It is an extract from his upcoming autobiographical novel In the Shadow of the USSR, in which Christopher Ejugbo (an engineer living in Taiwan who studied at the Riga Civil Aviation Engineering Institute from 1991 to 1996) recounts a protest action in 1992 against the loss of a prestigious scholarship at the Civil Aviation Institute. The collapse of the USSR is discussed in this narrative only from the point of view of losing the opportunity to receive funding to study in a developed country. Of course, this is also just one aspect of the ‘long-distance friendships’, but it could have been explored further.

The unrealised potential of the exhibition is to be found at the point where two different histories of oppression meet, namely, parts of Eastern Europe that recently have been occupied by the Soviet Union and Global South countries that were violently subjugated by Western empires. What patterns of relationship do they form? We know the dynamics of the relationship between the oppressor and the subaltern, but how does one oppressed culture interact with another? Furthermore, how did the concept of ‘friendships of peoples’, advanced by Marxist theory and exploited by Soviet imperialism, construct the relationships between these peoples and nations? These questions need critical examination, which has been a missed opportunity by the festival and its curatorial framework. Writing about the role of Latvian filmmakers in the collaboration processes between Soviet cultural policy and African film history, film critic Elīna Reitere points out that during the Soviet period, Latvian film critics had no interest in film festivals in the Third World countries, which may have been a reaction to the conjuncture of Soviet ideology - thus automatically excluding from their attention cultural events which Soviet ideology “forced them to watch”.4

The other aspect that seems to have been overlooked is the legacy of the Latvian theoretician and artist Voldemārs Matvejs (1877-1914), who is only mentioned in the conversation between Alicia Knock and the Beninese historian and writer Dieudonne Gnammaknou, who graduated from the Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow in 1991 and has written a thesis on the African presence in Imperial Russia. The conversation is published in the exhibition catalogue and highlights Voldemārs Matvejs’ unusual approach towards African art. The way Matvejs read and decoded African art differs from the colonial views that dominated Europe in the 1910s. Matvejs insisted on the freedom of creation of African artists, and his understanding did not include racist discourses. Matveja’s legacy represents one of the most fruitful connections between Latvian and African cultures that can be called friendship without any ironic subtexts. It would have been highly beneficial to transform Matvejs’ ideas from Latvian art history into this contemporary art event.

Looking at the subjugation of the Eastern European and African regions to Russian imperialism, both the individual stories and their encounters, I find it difficult to read any interpretative nuances, except the call to talk about these issues and create new territorial geometries of friendships. Most of the works are newly produced (a rare and welcome practice), making the avoidance of the current political realities even more puzzling. The stories underlying the works in the exhibition seem to have been thrown into a kind of performative limbo, waiting for them to self-organise. There is a lack of deeper nuance that would tell us about the historical events of these nations (unfortunately, the descriptions of the works are also too superficial to provide an adequate understanding of these complicated histories. It is a stretch to think that an average Latvian viewer would have access to their specificities and regional nuances. For these reasons, it is not entirely clear what the exhibition’s aim was. Perhaps curators were keen to avoid a patronising white gaze and tried to make the exhibition more direct without intersecting the artists’ messages with their own perspectives. It seems that organisers let the exhibition’s subjects (artists/artworks) fully speak for themselves but forgot to provide translation, which is an essential aspect of friendship between distant regions and nations, isn’t it?

From a formal perspective, static and moving image art dominates the exhibition, primarily engaging the sense of sight, and only a small proportion of three-dimensional works gives the exhibition a slightly flat impression. Perhaps this is why the rare works that are more spatially dynamic, such as the video in the installation The Albanian Conference by Anna Ehrenstein with DNA, Vidisha-Fadescha, Shaunak Mahbubani & Rebecca Pokua Korangi or Jeanne Kamptchouang’s installation ‘Abattis (Giblets)’ from dismembered and rearranged chairs, leave a deeper impression on the viewer. Concerning scenography, artworks are also spatially ‘befriending ’ with each other, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them. The artworks overlap spatially with each other, the exotic architecture of the market, and the imprints of its interior history. There are various leftovers from the everyday life of market stalls, signs, calendars, advertisements and other visual microelements. Given that many works in the Survival Kit are made of simple, everyday materials, crafted in DIY techniques and exhibited alongside historical artefacts, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between an art exhibit and a random element of the environment. The exhibition’s layout is not entirely successful in terms of the reception of the works, but with the large, open space interspersed with small chambers, the space is intensive as an explorable dynamic between transparency and enclosure.

Every year, Survival Kit takes place in partially abandoned spaces, initially drawing attention to the economic turmoil and the problem of unused spaces in Riga, but in recent years, it has also increasingly interacted with meanings that are produced by spaces’ former functions. Vidzemes Market, where Survival Kit 14 took place, in part functions as a stereotypical metaphor for the Eastern market, although architecturally, I associate it more with the ceiling of the Musée d’Orsay.

Some works are deliberately scattered all over the space, like Šejla Kameric’s stunning excerpts from the ‘Survival Guide’– a guide for extreme urban conditions and human resilience–based on evidence from the 1992-1996 siege of Sarajevo. These excerpts unexpectedly strike the visitors with phrases like ‘how to survive, but also how to die’, ‘Shocking. Difficult. Sickening. Brueghel and Chagall at the same time’, ‘markets were the aggressors’ favourite targets’ on the building’s walls, windows and floor. Kameric’s work literally and spatially illustrates the tension of distance while simultaneously repeating the market’s chaotic nature.

The context of the venue also appears in Evita Vasiljeva’s installation Illogical conclusions from accurate assumptions, where absurd models of utopian architecture interact in a visually expressive way with fruits and berries that come from other countries out of season and become “exotic” guests in Latvia.

In their curatorial statement, curators use the metaphor of the market to explore the possibility of friendships outside the conditions of the market: ‘What new kinds of transactions might be supported, based on exchange and gifting or fragmentation and impossibility?’. These seem to be relevant questions in all times and circumstances, but perhaps there is more “distance” in contemporary friendships than ever before, and perhaps the exhibition’s concept will evolve from an exaggerated approach to a normative definition of friendship.