Gaziantep-Aleppo border landscape, 2014. Courtesy Kemal Vural Tarlan and Kitchen Workshop, Gaziantep. Photo: Kemal Vural Tarlan

Merve Bedir is an architect and founding member of the Kitchen Workshop and Center for Spatial Justice in Turkey. Her work revolves around infrastructures of hospitality and mobility. She has a PhD from Delft University of Technology and a BArch from Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

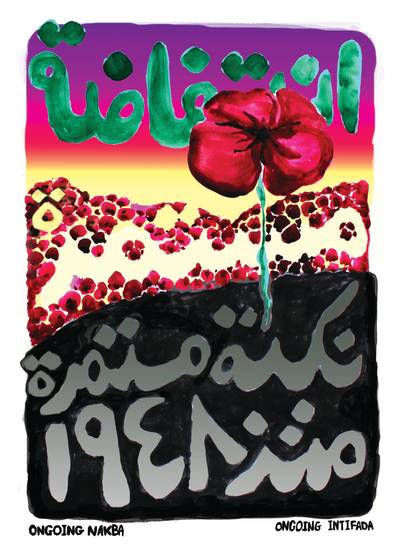

In the border region between Turkey and Syria, disaster after disaster, people who are already vulnerable are asked to be more resilient and to endure the pain. While state and international agency responses to each disaster—post-revolution migration (2011), the Covid-19 pandemic (2019), and the February 6th earthquakes (2023)—have shown their ineffectiveness and obsolescence, people and communities on the margins have self-organized networks of mutual aid for survival. In this essay, I take ‘disasters’ as thresholds to explain that nothing is natural about them but the underlying infrastructures and injustices that push people and beings to the brink of extinction. I further emphasise that the self-organized mutual aid networks demonstrate the necessity and potential for building alternative futures outside the deepening systems of oppression, racism, and discrimination that these disasters exacerbate.

I’m an architect, raised in Turkey and living in the Netherlands, and have been volunteering for an NGO, Kırkayak Kültür, in Gaziantep since the revolution in Syria. I started working with the migration between Amman and Istanbul in 2013, co-taught a summer research seminar together with Nora Akawi and Nina Kolowratnik at Columbia GSAPP, and then I curated an exhibition, Vocabulary of Hospitality, in Studio X Istanbul. The people I met during this time and tracing their migration led me to Gaziantep, a city on the Turkish side of the border with Syria, across from Aleppo. There, I started volunteering at Kırkayak Kültür and, in 2015, supported a collective of women to initiate the Kitchen Workshop.

I acknowledge the people of the region who, despite perpetual displacement and dispossession, uphold human rights and the rights of other living beings to coexist. While I write on my own behalf, my voice inevitably connects to the different collectivities and communities I am part of. I cannot claim to speak for them, but their stories compel me to write.

(Auto) colonising Infrastructures and the New Elite

In her text, A death that reminds suicide I and II (2023), Ayşe Çavdar explains the consequential destruction of the February 6, 2023 earthquakes across Turkey and Syria and about the new urban class and financial/religious identity that builds and entangles with the rapid urbanisation and its economy in Turkey, since the Law for Transformation of Areas Under Disaster Risk (commonly known as Disaster Law) came into effect in 2012. I want to highlight this analysis and address the related agents of urbanization: politicians, technocrats, disciplinary practitioners, workers, and inhabitants. For instance, Pazarcık, the epicentre of the main earthquakes of February 6, is the base location upon which seismic and structural calculations are made, and this earthquake has been ‘the model’ of these calculations for the region for decades.

Additionally, concrete is the primary material and system of contemporary construction that no one questions, while the knowledge of so many other methods of construction is unseen. Or the entrepreneurs who have worked in construction as a business in the previous twelve years because it’s lucrative, or the building inspection mechanisms that have unseen the cheap and dangerous building processes, or the citizens who have undergone heavy mortgage schemes to live in new houses, more ‘modern’ buildings, unseeing the ancestral knowledge about their geographies about where and how to live. So, I dare to say that this is a collective suicide, in which there are many casualties but also many that are complicit.

Such spectral dimensions of the colonial infrastructures resurfaced with the earthquake. The threshold of pain and vulnerability was the “status-less” people’s endurance to disaster after disaster, in the ruins of the empire, under nation-state regimes. The result is a further extinction of the indigenous peoples, cultures, and histories under (auto) colonialism and its complexities in the region.

I also need to add the colonial infrastructures in entanglement to this context. First is the colonial imperial context: one of the districts of Gaziantep that completely flattened to the ground in the earthquake had been relocated to its current place as part of the Berlin Baghdad railway construction of the German and Ottoman Empires at the turn of the 20th century. The soil quality in the new location was good for agriculture and 1-2-storey houses, not high-rise apartments. This relocation destroyed agricultural land/soil back then and made way for its future, i.e., the current destruction caused by the earthquake.

Second is the colonial modern context: The structural racism against Arabs, Doms, and others in the aftermath of the earthquake. For instance, while everybody else was transferred to containers, Dom people around Gaziantep remained sheltered in tents organised by Turkey’s disaster mitigation and relief agency. Fearing that they would not be rescued or worrying about what would happen to them after being rescued, Syrians have hesitated to voice (in Arabic or Arabic accent) for help from under the rubble in the destroyed buildings.

Such spectral dimensions of the colonial infrastructures resurfaced with the earthquake. The threshold of pain and vulnerability was the “status-less”1 people’s endurance to disaster after disaster, in the ruins of the empire, under nation-state regimes. The result is a further extinction of the indigenous peoples, cultures, and histories under (auto) colonialism and its complexities in the region.

Surviving Unjust Lands

Gaziantep is one of the largest cities in Southeast Turkey, where one-fifth of the population is from Syria, and the city is in the earthquake zone. My engagement in Gaziantep is specific to Kırkayak Kültür, an NGO in the city. They have stated their mission as an organisation for culture, migration, and ecology in their founding in 2011. I have been volunteering for them since 2014-15, after the mass migration and displacement of people from Syria to Gaziantep after the Revolution in Syria. We (the women in Kırkayak Kültür, friends of Kırkayak Kültür) initiated the Kitchen Workshop as a result of a years-long practice of solidarity and conversations on how to engage with the migration from Syria meaningfully. The Kitchen Workshop is where women from Turkey and Syria have been actively working/living with the question of how to live together beyond an understanding of emergency and humanitarian support.

Kırkayak Kültür, Stone House, 2014. Courtesy Kemal Vural Tarlan, Gaziantep. Photo: Kemal Vural Tarlan

Kırkayak Kültür is in the Bey neighbourhood, a former Armenian neighbourhood in Gaziantep. Many buildings in this neighbourhood had been empty for decades after the Armenian genocide (1915-) and, over time, have been inhabited temporarily by people who were forcefully displaced after the state’s village evacuations in the Kurdish regions of Turkey in the 1990s, as well those who arrived from Idlib, Aleppo, and other cities after the Revolution in Syria (2011). As I see it, the work of Kırkayak Kültür, since its beginnings, is an act of repair, despite the lack of reparations, because their work acknowledges and is actively engaged in the Bey neighbourhood and its people that have been inhabiting and living with the erasures, displacements, and destructions. Kitchen Workshop tries to think and make space with migrants, looking for sustenance for justice in unjust lands and unconditional hospitality in hostile infrastructures, questioning our position and responsibility within all this. This is, for me, where our friendship stems from.

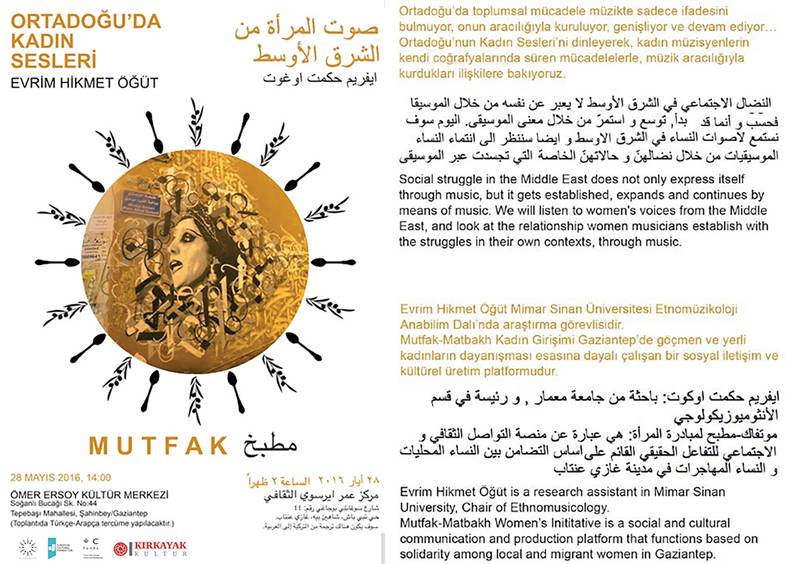

Women’s Voices from the Middle East, poster for a music event by the Kitchen Workshop, 2016. Poster design: Merve Bedir. Courtesy Kitchen Workshop, Gaziantep

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, Kırkayak Kültür has been working on-site, providing practical assistance such as food, medicine, accessible information, etc., to the marginalised communities that have been invisible to the state. In addition, Kırkayak Kültür has been documenting the cases of racism and discrimination, especially against the migrants from Syria and Dom people, after the earthquake. I wasn’t in Turkey when the earthquake took place – asbestos cloud in the air, Dom people in tents, and construction rubble (also with asbestos, of course) being emptied/collected into Amik Valley are images still vivid in my memory from the time of seeing them through social media. Friends in Kırkayak and Kitchen Workshop advised me not to rush there immediately. Considerable support and aid were being organised by local groups and the diaspora, as well as through digital networks of solidarity, feminist and queer networks of solidarity, people leaving for the region in rotation to serve in their specific expertise. For a moment, this surprised me; I wasn’t expecting the people in the country to be so willing to run for help. Since the 2010s, Turkey has been so polarized and dissolved into (in)dividuals, everybody seeing each other as part of doctrines, camps, and enemies, where it seemed like nothing collaborative/collective could happen even amongst closely connected families, but the earthquake brought everyone together.

What Is to Be Rebuilt?

In the aftermath of such a large disaster, repair or rebuilding is very difficult to discuss simply because of the scale and spread of death and damage. Remember the maps made in its aftermath, showing the earthquake region covering one-third of France. Thinking of this reality about the 7 Richter earthquake in the Marmara region in 1999, which also caused mass death, this not-so-natural disaster across the border region between Turkey and Syria triggers nothing less than rage. An important question is why and what is to repair and rebuild in this context.

Is a “great” repair even possible? How long does it take? What is the scale of its operation? What are its thresholds? What will happen if this scale of catastrophe doesn’t make us question building in concrete with efficient recycling mechanisms or other assumptions embedded in our work?

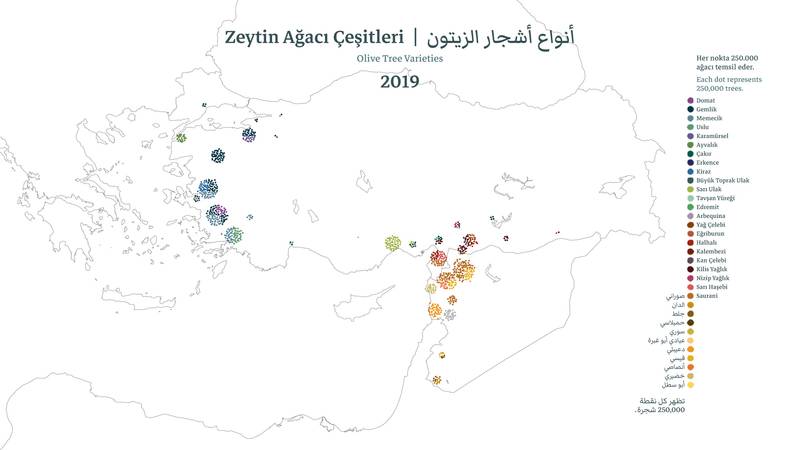

A state should be about not letting an earthquake have such destructive consequences. Amik Valley comprises the most resourceful agricultural sites, soil structures, and the region’s oldest pistachio and olive trees. If not to avoid such destruction, if not to plan for the proper removal of concrete rubble, what is the use of a state? Who is repairing what, why and for/with whom? Then, architects, actually most professional technocrats, are solution-oriented people. Their default mode of operation is to solve problems rather than asking the fundamental questions. Is a “great” repair even possible? How long does it take? What is the scale of its operation? What are its thresholds? What will happen if this scale of catastrophe doesn’t make us question building in concrete with efficient recycling mechanisms or other assumptions embedded in our work? Then, the rage is for the people invisible to the modern state, marginalised, oppressed, living dependent, living in poverty, the people who don’t profit from the rapid urbanisation and its financial economy but who are killed as part of the collective suicide I’ve been referring to, outside their will to participate, and in the aftermath of the earthquake who cannot leave the region because they don’t have the means to, who work in hazardous conditions pulling down the heavily damaged buildings, or who went back to heavily damaged buildings because there was no temporary living space created, or who couldn’t survive the freezing cold in February. Here, I’m thinking of the limits of extractivism. Where does capitalism stop, not only from extracting from the land and earth for the sake of new construction but also from extracting their lives from the humans, migrant workers, unregistered workers, and people who are deemed disposable?

Olive Tree Varieties in Anatolia and Fertile Crescent, 2019. Courtesy Deniz Cem Önduygu and Kitchen Workshop, Gaziantep. Map by Deniz Cem Önduygu and the Kitchen Workshop.

Olive Gardens of the Border Landscape, 2019. Courtesy Kemal Vural Tarlan and Kitchen Workshop, Gaziantep. Photo: Kemal Vural Tarlan

When I arrived in Gaziantep a month after the earthquake, I worked in the Nurdağı and Islahiye, two districts almost flattened. Kırkayak Kültür and Kitchen Workshop had been distributing help in these districts. Some members of the Kitchen Workshop, mainly women from Aleppo, started cooking in a restaurant’s kitchen and distributing the food in these districts. This is a paradigm shift, where roles change in practice: the migrant helps the citizen, the guest becomes the host, and new life with its values in practice amongst the rubble.

Negative Commons and the Need for Possible Futures

It is important to note that the Kitchen Workshop didn’t start as a kitchen. It was a space of solidarity, a safe space, but more importantly, a space for cooking ideas of living together. Kitchen Workshop worked with different ways of continuing with these ideals through displacement, racism and discrimination, undocumented work, the COVID pandemic and further invisibility. Then came this earthquake. Among all this is a shared struggle around the rights and collectivity of women, as well as the kind of solidarity practice and mutual aid. Following the work on-site in Nurdağı and Islahiye, we decided to start an industrial kitchen in Gaziantep, one that can cook in mass, so the women who want to stay in Gaziantep can wait, and also a mobile kitchen so it can move and bring food to different places. The work is for working towards a new life, new practices, and new instituting where you can have specific non-extractivist and no-dig values, so it is a desire and an obligation—the aftermath of a disaster but the immediate networks of solidarity and mutual aid that create temporary commons.

The knowledge of picking olives Syrians, which looks primitive and ancient to the modern state, comes in as knowledge of survival in this case and is precious but outside the scientific understanding of merit. I keep thinking about how to collectively think about the ways of living together, the political agency of communities, and what and who it is to relearn with/from. Here, I think of another part of the question of merit and knowledge as a specific act of digging.

It is crystal clear that these structures are the ones to depend on for survival and the infrastructure of a collective future. But how do we sustain them? How do we transform them from survival structures to infrastructures of collective futures? I would like to think of these infrastructures for people’s survival and people’s collective futures, for the region but also beyond, thinking of sisters and friends in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and further, also referring to an agency of diasporas in the world we live in.

Who has the right to repair, but also who has the right to construct? Who has the knowledge and merit? I’m thinking of this one instance where women from Idlib in the Kitchen Workshop taught women from Gaziantep how to pick olives. Because Turkey has modernised agriculture, people don’t use the old techniques anymore, so they are out of practice and forgotten. The knowledge of picking olives Syrians, which looks primitive and ancient to the modern state, comes in as knowledge of survival in this case and is precious but outside the scientific understanding of merit. I keep thinking about how to collectively think about the ways of living together, the political agency of communities, and what and who it is to relearn with/from. Here, I think of another part of the question of merit and knowledge as a specific act of digging.

The invisible infrastructure of autonomy hasn’t been utilised, which I call “cityzenship”, articulated in the constitutions between 1921 and 19382. We use this principle in the Kitchen Workshop as a basis of agency and belonging, as shown in the examples I offered, such as learning to pick olives and setting mutual aid networks. These principles and practices can be beneficial in operating towards and increasing the political agency of science and community in the aftermath of the earthquake.

4000-year-old olive seeds found at the Oylum Höyük archaeological site in 2015. Courtesy Atilla Engin, Gaziantep