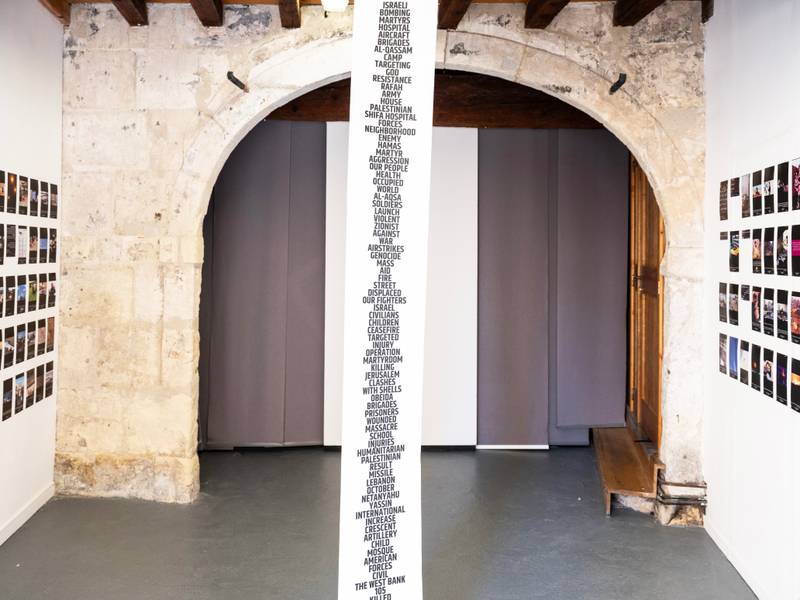

Installation view from the activation ‘Against Abstraction’ by Maen Hammad, Dina Salem, Sari Tarazi, and Ahmad Alaqra | Photo: Mathieu Asselin

Sheung Yiu (HK/FI) is a Hong Kong-born, image-centered artist and researcher based in Helsinki. His practice explores the act of sensing through algorithmic image systems he calls Hyperimage. He looks at photography through the lens of new media, scales, and systems to contemplate how cyborg vision transforms ways of seeing and knowledge-making. When he is not making photographs, he writes about photography.

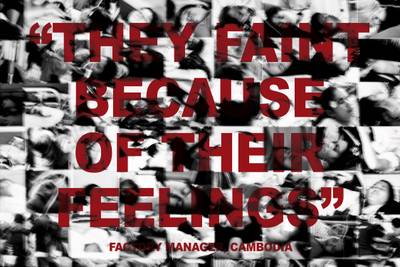

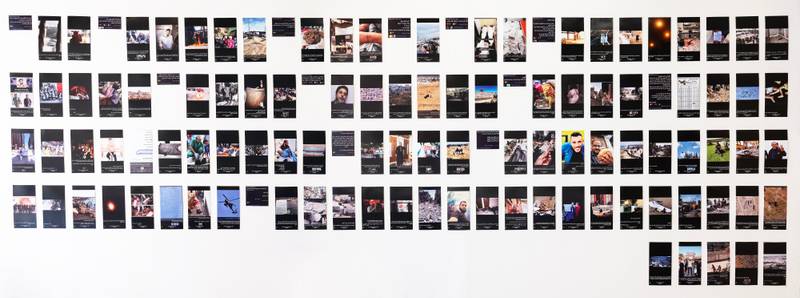

In a quiet alley of Arles slightly hidden away from the hustling and bustling of the city-wide photo festival Les Rencontres d’Arles, a crowd listened intently to Maen Hammad. The narrow alley could not contain the number of attendees at the opening of Against Abstraction. Several times, his speech was interrupted as the attendees had to close into Hammad and give way to passing cars. Sitting next to him, curatorial advisor Tanvi Mishra was also listening. Behind them was the humble exhibition space, where more than 200 screenshots printed on fine art paper were fixed onto walls. The images are neatly arranged into four rows in chronological order. Visitors are handed a document translating the Arabic captions into English and French. At the heart of the exhibit, a piece of fabric hangs from the ceiling, serving as a centrepiece. On one side, bold black words in Arabic; on the other, their English translation. Words like “Shifa hospital,” “health,” “civilian,” “martyrdom,” and “child” anchor the viewer in the somber reality of the scenes depicted.

Vernissage of ‘Against Abstraction’ at Double Dummy Studio, (L to R) Tanvi Mishra and Maen Hammad

Installation view from the activation ‘Against Abstraction’ by Maen Hammad, Dina Salem, Sari Tarazi, and Ahmad Alaqra | Photo: Mathieu Asselin

The minimalistic installation of tiny images, fixed to the wall by steel pins, starkly contrasts with the immaculate framing and expensively printed photographic artwork in the surrounding exhibitions of Les Rencontres d’Arles. Photographers featured in the prestigious photo festival are either big names in the industry or up-and-coming global talents. Now in its 54th edition, the photo festival has grown into one of the biggest and richest in the world, with institutional support from the Ministry of Culture in France, BMW Group, and the Provence municipality. In comparison, the visible lack of production budget in the installation of Against Abstraction, whether due to realistic constraints or a conscious design decision, presents a clear counter-aesthetic to the main events.

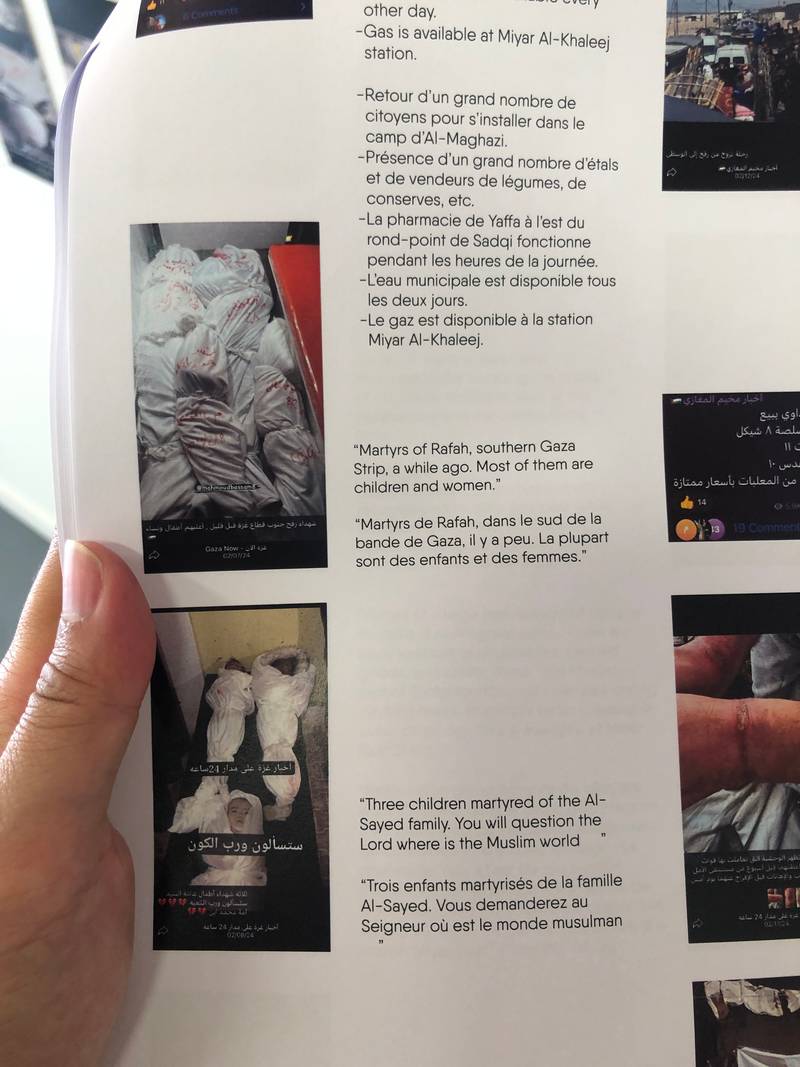

I stepped inside and looked closely at each screenshot: a wounded child, body bags, bullets, and the lifeless face of a victim buried under a rumble. It can’t be clearer. The images are scenes from the ongoing Gazan Genocide, except they are not captured by professional award-winning photojournalists but taken by Gazans for Gazans. Palestinian artists and photographers, Maen Hammad, Dina Salem, Sari Tarazi, and Ahmad Alaqra have been collecting screenshots from seven active Telegram channels daily since October 7, 2023. They analyzed and selected the most frequently used words in these communication channels, then chose one audio, one photograph, and one video source to represent each word. These images are the most unfiltered, raw depictions of the ongoing genocide you will ever see—uncensored by social media and unedited by any photo editor in any news agency. These are the images taken with no pretension but the pure intention to communicate, warn, and document. These are the photos taken by people in the warzone without the press vest. This is as real as it gets.

The photo exhibition is a public intervention staged by the Palestinian artists at the invitation of Double Dummy Studio founded by photographer Mathieu Asselin and curator Sergio Valenzuela Escobedom with the mission to highlight crucial social issues and critical discourse on photo documentaries. In 2022, in response to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Les Rencontres d’Arles put up a statement in support of the Ukrainian people and their fight for freedom on the festival’s announcement page. This year, as Hammad poignantly pointed out on the opening night, no similar official statement has been drafted in support of Palestinians. The double dummy studio space is all they’ve got.

Against the Ambiguity of Image

The US-based Maen Hammad is the only artist from the group who was able to make it to the festival. The rest of the group is in the West Bank. When Tanvi Mishra approached Hammad with an invitation to create an exhibition in Arles, he initially rejected the idea. The upscale, posh atmosphere of the festival seemed entirely offputting for showcasing the ongoing genocide of his people. He only accepted with his team when Mishra explained the goodwill of Double Dummy Studio. For the exhibition, the Palestinian artists, some documentary photographers themselves, refrained from showing their work but decided to give the spotlight to vernacular images, ‘everyday’ scenes captured by everyday people. The decision comes from a reflection on how we, living in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) countries, are bombarded with images of the genocide on social media platforms and Western news outlets. Yet, these images, captured by professional photojournalists, are more often than not abstract rather than showing the everyday reality of Palestinian people.

When protesters chant Free Palestine across the world, what is the freedom they are demanding? The concept of freedom is inherently abstract, and with each chant, its meaning dilutes until it becomes little more than a vocalized expression on the street. For Gazans, freedom is freedom from murder on a grocery trip.

The list of words occupying the center of the photo exhibition reflects the central role words play in the exhibition. Photographs often aestheticize violence, creating visual interest while maintaining a safe emotional distance through abstracting reality; words contextualize and clarify. Hammad emphasized the importance of text in this project multiple times in his sharings, directing the visitors’ attention to the captions in Arabic below the images written by the senders in the Telegram channels. In life-and-death situations, ambiguity leads to misunderstandings, and misunderstandings cost lives. For him, the accompanying text might be even more important than a screenshot of violent images. Words eliminate ambiguity. An image of a wounded child in a hospital bed, a result of an Israeli airstrike, visually conveys the cruelty of genocide. However, it is the child’s name in the caption that transforms the abstract concept of brutal violence into actionable reality. This photo exists not only as proof of senseless violence inflicted on the innocent but also to identify the child so that their family knows where to find them. A photo isn’t worth a thousand words, not when lives are at stake.

Image caption reads ‘Yeast in the market for 16 shekels’ | Photo by Sheung Yiu

Caption sheet from Against Abstraction | Photo by Sheung Yiu

Words show a lot of nuances from what’s besides sellable, violent, eye-catching images of conflict. Another screenshot on the wall shows a curious image of a stack of red and white packages. On each bag is a cartoon of a chef holding a comically-sized croissant. The caption says: yeast in the market for 16 shekels. Hammad continued explaining the importance of these deceivingly mundane photos. The image carries the message that people can make bread. They can finally eat. It says, “Come and get it.” Another image: a destroyed city with a red hand-drawn circle and an arrow. The caption reads, “The presence of occupation forces in the eastern areas of the Bureij camp in the central #Gaza Strip.” Gazans used these visuals in telegrams to warn each other of their daily military presence, as a trip to get food could have gotten you killed. Earlier this year, as many Gazans rushed to obtain food from aid trucks in the besieged Palestine facing inevitable famine, Israeli troops opened fire on civilians, leaving at least 112 Palestinians killed. Israeli officials denied the allegations, saying the people were trampled to death by trucks as they fought to get food. The event will later be coined the Flour Massacre or the Bread Massacre. Few in the Western world would have heard of the event besides the universal call to Free Palestine.

To the surprise of many visitors, “Free Palestine” does not rank among the most frequently used words on the Telegram channels. On the day when the image of yeast was shared, the word that dominated was “aid.” When protesters chant Free Palestine across the world, what is the freedom they are demanding? The concept of freedom is inherently abstract, and with each chant, its meaning dilutes until it becomes little more than a vocalized expression on the street. For Gazans, freedom is freedom from murder on a grocery trip. On the telegram channels, Palestinians are not killed; they are “martyred.” The exhibition offered a glimpse into the media shared on Telegram, portraying it as a vital open-source citizen intelligence tool for surviving the ongoing genocide. It represents a deliberate choice to present the reality of genocide without abstraction, providing a direct and unfiltered perspective on the harsh realities faced by Palestinians.

Against Aestheticization

The critique of photojournalism and war photography is obvious here. Against Abstraction problematized parachute journalism, the practice of placing journalists into an area to report on a story in which they have little cultural context, often leaving the area as quickly as they arrive when the ‘action’ is over. The screenshots on the wall are the strongest rebuttal to parachute journalism, challenging the long-held justification for their presence in the front line that proximity gives authenticity to their photographs. These images shared by Gazans are as close to the experience of genocide as you can get because they are not chasing the ‘action’. The bullets are coming at them. Smartphones and social media gave the oppressed the tools to document their demise and speak for themselves. Citizen journalism frees these images, bypassing the content moderation of mainstream social media platforms and the aesthetic abstraction of photojournalism.

In an artist talk two days before the opening, Hammad recounted his experience as a Palestinian photographer documenting Palestinians’ fight for freedom on the ground. He recalled a moment when foreign photojournalists arrived. Hoards of photojournalists immediately spread around the city, combing through the rubble. Like vultures, they search for blood and dead bodies, rushing to take photographs. For a while, he felt that the noise of the shutter speed was so loud that it seemed to drown out the cries of injured children inside an ambulance. He reflected on how photojournalists, focusing their lenses on lifeless bodies, seemed to inflict another layer of violence on Gazans: first shot by the Israeli army, then shot by photographers. At that moment, his dissatisfaction with photojournalism and his disdain for the industry crystallized. It was as though the darkest aspects of the photo world had materialized right before his eyes.

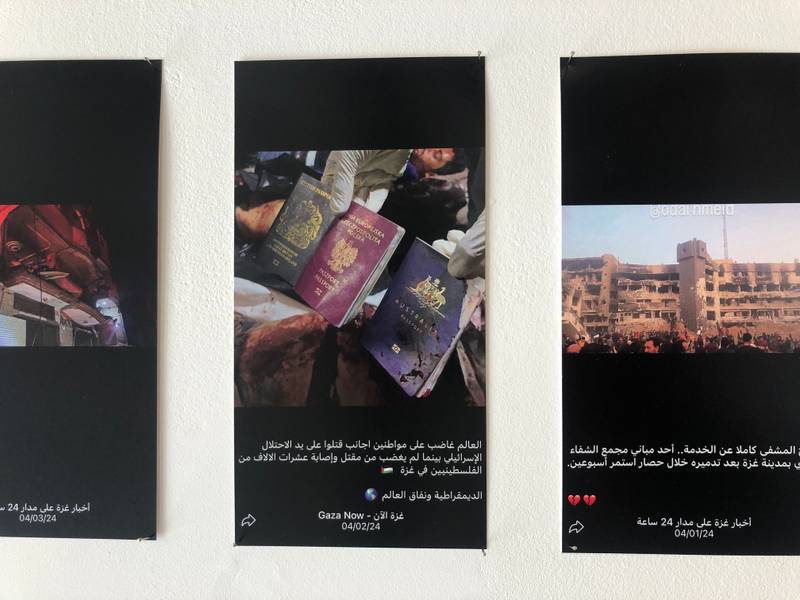

Image on the left: The hospital is completely out of Service. One of the buildings of the Al-Shifa medical complex in Gaza City after its destruction during a two-week siege.

L to R: Mass grave in Rafah for about 80 martyrs after the occupation released the bodies it had kidnapped from the Gaza Strip during the war; Martyrs of the Al-Bureij and Al-Maghazi massacres in central Gaza; Urgent… Update: The number of martyrs in the Al-Maghazi massacre has risen to 80 so far.

Photojournalists employ a humanist pictorial language rooted in Renaissance traditions to beautify and abstract horrific scenes. The grid system and the golden ratio are among the first compositional rules a photographer learns. A mother hugging a child is formulaically composed to evoke the imagery of Michelangelo’s La Pietà.

The public tends to over-romanticize the role of war photographers. And war photographers tend to aestheticize violence. The Zimbabwean-American writer Zoé Samudzi, who was Maen’s conversation partner at the talk, observed that the perceived artistry of photo documentaries often excuses their questionable presence and exploitative practices. Photojournalists employ a humanist pictorial language rooted in Renaissance traditions to beautify and abstract horrific scenes. The grid system and the golden ratio are among the first compositional rules a photographer learns. A mother hugging a child is formulaically composed to evoke the imagery of Michelangelo’s La Pietà. Many award-winning entries of the World Press Photo are sprinkled with classical painting iconography and religious motifs if one observes closely. These beautifying techniques and deliberate composition make ugliness palatable. At the same time, it elevates the work of photojournalists into that of an artist. Looking back at the history of photography, the appropriation of romantic visual language is not an exception but a convention. During the early 20th century, in the infancy of the medium, pictorialist photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz employed similar tactics to elevate the status of photography from the mere mechanical reproduction of reality. As writer Allan Sekula puts it, “The invention of photography as high art is founded fundamentally in the rhetoric of romanticism and symbolism.”1 Aestheticization thus becomes a justification for their presence and influence over their subjects. With an air of prestige and visual expertise, photojournalists assert their right to photograph, publish, and freely sell their work.

However, this abstraction through artistic language not only beautifies the scene but also glorifies the roles of war photographers, thereby justifying the additional violence and exploitation inflicted on Gazans’ bodies. Mastery over aestheticization had allowed these photographers privileged access to conflict zones with relative immunity (which is not true anymore as the war in Gaza is one of the deadliest for journalists in recent history). Yet, the photos they deliver often lack compassion and substance. The abstraction they employ presents a sanitized and skewed reality. These photographers leave Gaza with images stripped of context, later winning World Press Photo Awards, opening exhibitions, and selling their works to news outlets. Against Abstraction is an attempt to upset the visual order, to challenge the authority of war photographers, and to empower the powerless.

Against Content Moderation

Aesthetics concerns beauty and pleasure.Aesthetics encompasses subjective social conventions, which are historically contingent and culturally specific. Aesthetics are decisions made based on taste. Composition is aesthetics. Style is aesthetics. Editing is aesthetics. Framing is aesthetics. Equally socially constructed is the ethics of censorship. Traditional news media establishes best practices and guidelines for depicting violence. Reuters’ code of conduct, for example, states that journalists have “a duty to be aware that such material can cause distress, damage the dignity of the individuals concerned or even in some cases so overpower the viewer or reader that a rational understanding of the facts is impaired.” In practice, these guideline translates into censoring graphic images. Social media content moderation inherits the practice from traditional media, where bloody, nudity and violent images are censored indiscriminately, often taken out of context. The content moderation logic is an abused tactic for platforms to enact systematic political censorship. There have been multiple cases of Instagram and X censoring pro-Palestinian messages. Images on Western media are on one hand sanitized, and on the other, skewed based on the political affiliation of the platform. As an outsider navigating the deluge of images and disinformation, it is increasingly harder to discern what is truly happening in Gaza.

If we live in a world where soldiers are murdering children and raiding hospitals, should we censor the images to minimize emotional distress, or do we, as a member of humanity, have an obligation to see a young lifeless body and acknowledge our collective responsibility?

Censorship and aestheticization are two sides of the same coin. Both are forms of abstraction. Censorship redacts reality for the sake of social decency; Aestheticization reframes reality to present a more desirable version. In photojournalism, these two forms often coexist. Aestheticization can bypass media censorship on violence by abstracting scenes through framing, presenting close-up shots of destruction, or cropping out faces and viscera. This abstraction distances viewers from the messy and dirty reality.

Telegram presents a compelling case study in contrast to dominant social media platforms like Instagram. Images shared among small groups for communicative purposes on Telegram possess a sense of urgency and honesty that Instagram lacks. The unmoderated portrayal of brutality on Telegram, sometimes predictably violent and other times unbelievably mundane, raises significant ethical questions: If we live in a world where soldiers are murdering children and raiding hospitals, should we censor the images to minimize emotional distress, or do we, as a member of humanity, have an obligation to see a young lifeless body and acknowledge our collective responsibility?

L to R: The killed officers and soldiers are the same among the officers and soldiers who boasted a few weeks ago of taking a photo in the Legislative Council in Gaza City. The eight were killed in the Shuja’iyya neighborhood, east of Gaza City; the occupation army shows a new picture of its arrest of dozens of civilians in Gaza.

Against AI-Generated Image and Social Media Activism

Back at the exhibition, another image caught my eye: a photograph depicting the sickening sight of the aftermath of a bombing raid—dozens of victims wrapped in white body bags surrounded by people captured from above, presumably captured professionally using an aerial drone. This is also the infamous image circulated on Instagram days after the AI-generated image of “All Eyes on Rafah” went viral. Users used the ‘real’ photograph to call out the fake image and underlying slactivism.

The AI-generated image is the most widely circulated post in Meta’s history. The image surfaced online on 27 May 2024 and was shared over 46M times within 48 hours. In the newsprints titled “Unbranding Liberation” launched on the opening night, Dina Salem and Maen Hammad wrote: “With an aerial view of an artificial container city, the image signifies the viewers’ passive participation rather than Israel’s brutal assault on the million Palestinians seeking refuge in Rafah. Devoid of any political fangs, it is being studied by corporate players and tech analysts as a model for successful “activist marketing”. It has served as a perfect example where the suffering, as well as the resistance of the colonized, is removed from its reality, stripped for consumption and freely laundered in digital space. It goes to show that the commodification of death and grief is no exceptional outcome of the system, but a feature of its design.”

Last year, war photographer Michael Christopher Brown ignited a debate in the photo community with his project 90 Miles, depicting Cuban history since the Missile Crisis. He used AI to generate subjects he wanted to document but couldn’t due to access. The generated images, based on real stories, resulted in generic and visually pleasing documentary images of Cuban life from the 1960s onwards. He minted the images as NFTs on Airlab, stating that 10% of the proceeds go to charities working with Cuban refugees. On the project website, he described the project as an “AI reporting illustration experiment exploring the decades-long story of Cubans crossing the 90 miles of ocean separating Havana from Florida.” The first thing you see on the project page, however, is a link to the NFT minting site. It is yet another illustration of photojournalism’s exploitative tendency to commodify other’s trauma.

However, the ‘real’ photograph circulating on Instagram in the name of Rafah is not of the Rafah refugee camp. The caption on the screenshot reads: “Martyrs of the Al-Bureij and Al-Maghazi massacres in central Gaza.”

What’s next for photojournalism?

I attended a workshop by Magnum photographer Bieke Depoorter with all this in my mind. Depoorter captured the industry’s attention in the late 2000s for her intimate portraits of strangers’ homes during her journey across Russian Siberia. As part of the famed Magnum Agency, the Belgian photographer was invited to document the Egypt uprising of 2011. The assignment instruction was simple: exercise your creative freedom. As a new-generation documentary photographer, she was well aware of exploitation in her field of work and the mistrust between the Egyptians and foreigners. For this assignment, she entered the living spaces of the laypeople during the revolution with their consent. She emphasized the importance of consent. She continued her earlier visual trope of taking portraits in intimate spaces, establishing an interpersonal relationship with her subjects. She was working on a photobook. Feeling that she failed her distant approach and failed to capture the reality of the country, she canceled the book deal. Instead, she went back to Egypt with her dummy book. This time, she went around asking Egyptians to write comments on the images. This would later become the photobook “As It May Be,” where she shows the images along with the unedited handwritten comments plastering all over her photographs. One comment suggested she should “redo the dummy book and capture more about the Egyptian civilization”.

Being from the same country does not exempt the photographer from the power dynamic between someone who has the privilege of studying abroad and earning a living through photography and someone who has lost everything. Within ethnic groups, there are power struggles among socioeconomic classes. Even within the same family, as many photographers who delve into family histories show, photographers still extract the story of others for their own interests. Whether for artistic expression or financial gain, photography is a selfish act.

Words carry weight. Despite the thoughtful introspection she demonstrated in her practices, certain phrases she used during her presentation stung me, especially after hearing Hammad’s heartfelt lamentation: “The composition of Alex Webb,” “Invited,” “Book Project,” “Do whatever you want,” and “Treat my subjects as actors in a movie.” Given the context, when Depoorter said “Truth is not important,” she was rejecting the notion of objectivity in traditional documentary photography and her authority as a so-called Truth-teller (she has been questioning photo documentaries since the beginning of her career and has since moved on to a more artistic approach to visual storytelling.) The current scrutiny of photojournalism stays at the age-old discourse of objectivity and the importance of consent and seems to lack the vocabulary to capture Hammnad’s frustration with the medium. If anything, these words she uttered suggest that institutional change will be slow, and a paradigm shift is still far away. “I am hesitant to think the documentary photography world can digest us. But that is not our problem.” Hammad told me, a Magnum Foundation grantee himself.

The profound interrogation of war photography posed by Against Abstraction is not the first and won’t be the last. There will always be an underlying power imbalance between the photographer and the photographed subject. The colonial exploitation is the most apparent, but this power imbalance is nuanced and intersectional. When photographing victims in the West Bank, Hammad would stay and grieve with the families, paying respect to the deceased. However, being from the same country does not exempt the photographer from the power dynamic between someone who has the privilege of studying abroad and earning a living through photography and someone who has lost everything. Within ethnic groups, there are power struggles among socioeconomic classes. Even within the same family, as many photographers who delve into family histories show, photographers still extract the story of others for their own interests. Whether for artistic expression or financial gain, photography is a selfish act.

The critical discussions during the week did not offer any satisfactory resolutions, just like decades of critical writings in photography preceding this. This self-interrogation is endless. I asked Tanvi Mishra: what is the validity of photographing others after 75 years of occupation and the ongoing genocide? Mishra acknowledges the structural inequalities within the photography documentary tradition. The inherent power difference between the photographer and the photographed in any narrative device is inescapable unless we restrict ourselves to autobiographical storytelling. But it is also that difference within narratives that connect us with others in a way that builds empathy and solidarity. “I don’t think we can negate the inherent power differential between those making the image, and those they are photographing, just like we cannot negate the structural inequalities or differences that exist in our world. However, I would like to imagine the possibility of image-making as a kind of solidarity building, a form of relay—to carry the story forward on behalf of those who are suffering so as not to burden them with the responsibility of having to do so.” Mishra thinks the possibility of image-making can exist, potentially beyond “extraction” or “gain”. “I do believe that images have the power to shape public opinion–we have seen it in the case of Gaza and the mobilization of civil society and citizens across the world. However, I don’t have any romantic notions about it having an immediate impact on governing regimes, which perhaps is another broader discussion.”

During the opening week, the small medieval town in southern France transforms into the epicenter of the European photo industry. The who’s who of the photo world gathers in Arles. The town is filled to the brim with tourists and cultural professionals. Established photographers meet old friends. Professionals discuss future plans over lunch meetings. Young photographers attend portfolio reviews; others pitch photo book ideas to publishers at book fairs. The photo world keeps spinning without missing a beat.

Installation view from the activation ‘Against Abstraction’ by Maen Hammad, Dina Salem, Sari Tarazi, and Ahmad Alaqra | Photo: Mathieu Asselin

Vernissage of ‘Against Abstraction’ at Double Dummy Studio, (L to R) Maen Hammad and Tanvi Mishra