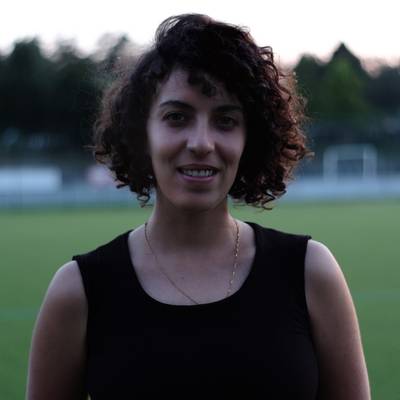

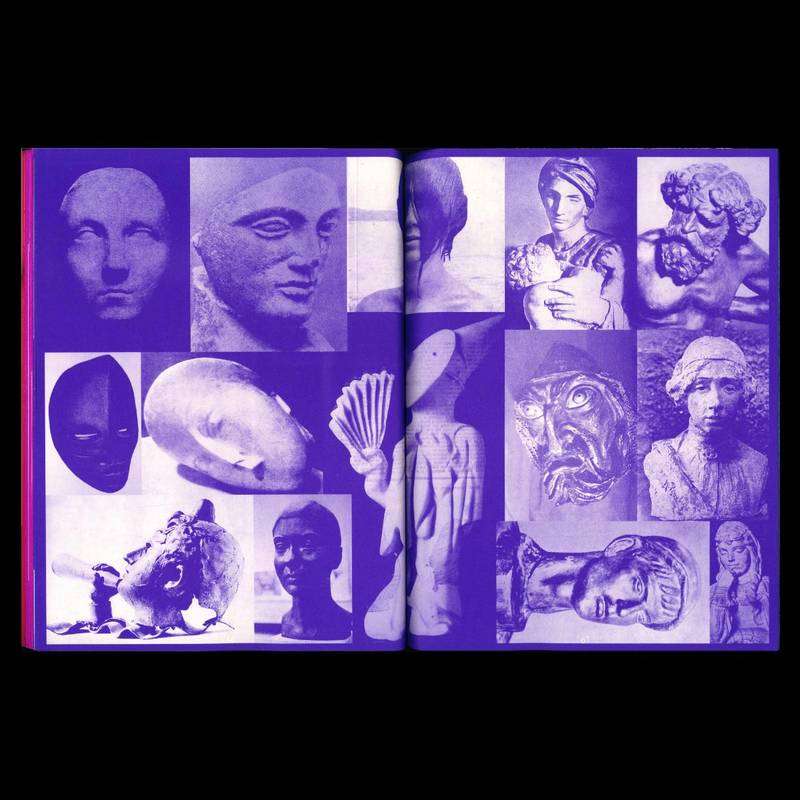

Spread from Kajet 05. Work by Sayam Ghosh

Martina Šerešová is a curator, producer and writer based in Helsinki. Her research revolves around ecologies and posthuman feminist thought, through which she approaches questions of time, speculative futuring and social transformation.

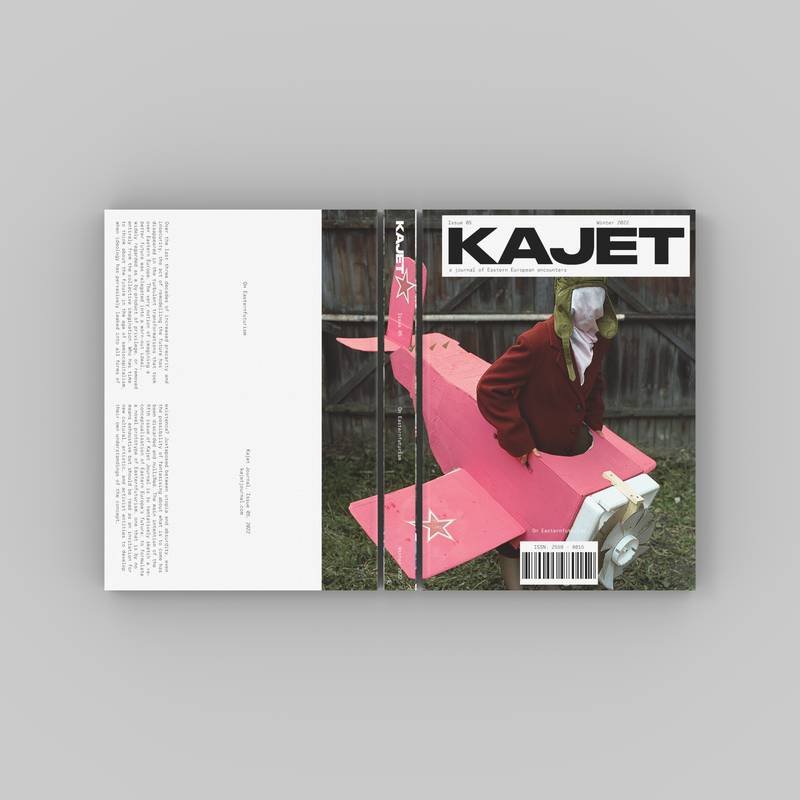

When I first heard about Kajet and the work of its editors, Laura and Petrică, I was excited. It felt like, finally, someone was addressing the complicated questions around contemporary ‘Eastern Europeanness’ and what often felt like a misrepresentation, misunderstanding or complete omission of the region and its identity in the ‘Western’ discourse. Through Kajet – a Journal of Eastern European encounters – Laura and Petrică offer a space for speculative reformulation of Eastern European identities, narratives and imaginaries, as an attempt towards what they call ‘a representation without purity’.

One day, we sat down with Laura and Petrică over Zoom to try to navigate this region’s slippery and ambiguous in-betweenness and complicate the binary narratives of periphery and centre, East and West, or present and past to seek a more complex and generative understanding of its diverse (and sometimes conflicting) perspectives.

MARTINA: In your work, you grapple with the complicated task of trying to represent the ambiguous region of Eastern Europe through providing a platform for Eastern European narratives, perspectives and imaginaries. Apart from Kajet Journal, you also publish The Future Of—a magazine that explores the futures of contemporary ideas. Can you talk a little bit about your thinking behind this future-oriented approach?

PETRICĂ: I would say that since we started Kajet, we identified certain ideas and concepts that we felt necessitated some kind of recuperation; they needed to be revived and brought back to life.

That’s why we also like to call The Future Of “the magazine of extinct ideas”—ideas that have seemingly lost their potential, that have been cancelled by history or this linear understanding of history, notions that have exhausted their appeal, that have been co-opted by conservative or regressive forces, or maybe have been completely forsaken from the collective imagination.

For instance, the first issue was about nostalgia. Can something be more futile, reactionary even, than longing for the past in a purely nostalgic fashion?

Of course, dealing with Eastern Europe in our work, I think being called nostalgic is almost an insult here. But we thought nostalgia can actually be quite productive, that there is potential in being nostalgic if you can transform it into a political tool, let’s say—not just thinking about the past, but about ways you can make use of these knowledges from the past, make use of these ideas for a better future. How can we reclaim a better future? How do we formulate new futures?

LAURA: We wanted to ask ourselves if there was some kind of emancipatory story potential behind the apparently retrograde gestures of being nostalgic. Can we reclaim this idea and repurpose it with some kind of social-political change in mind?

M: So it is nostalgia for times when we still believed better futures were possible? Rather than the nostalgia of bringing back the former regime, it is about reconnecting with a different kind of time filled with more agency and possibility.

L: Exactly.

P: Despite all these associations that nostalgia has, we argue that nostalgia is more than just a sentimental thing. Thinking about nostalgia, or simply being nostalgic, does not make us, I think we wrote in our editorial letter, “prisoners of history’’. With the right tools or with the right application, we might be able to become self-reflective beings, aware of the complexities of the past and the possibilities of the future. So, we seek to locate in nostalgia some kind of progressive potential and reclaim it from the forces that may have confiscated it in the first place.

M: I like the way you place nostalgia in relation to complexity—a tool for helping us not only see the complexities of histories but, by the same token, complexities of possible futures. As you say, nostalgia is so often accused of doing the exact opposite—being too simplistic or simplistically optimistic, even. It’s interesting to rethink nostalgia as a way of recognising complexity and the possibilities embedded in our pasts.

P: This idea of optimism and hope can also be added to this list of concepts that need to be reclaimed.

M: Absolutely. I also think there is a difference between hope and optimism, or between hope and naivety, at least. Václav Havel has this quote: ‘‘Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out’’ - so talking about hope as the conviction that there is meaning in doing good things, despite not knowing whether they will work out in the end. I think this is really something we forget when we think about hope.

L: It’s also an interesting approach today, in these times of pure self-help optimism, in which you’re bombarded with this ‘’You need to be positive!’’ attitude from everywhere. I think that it’s a good quote to keep in mind.

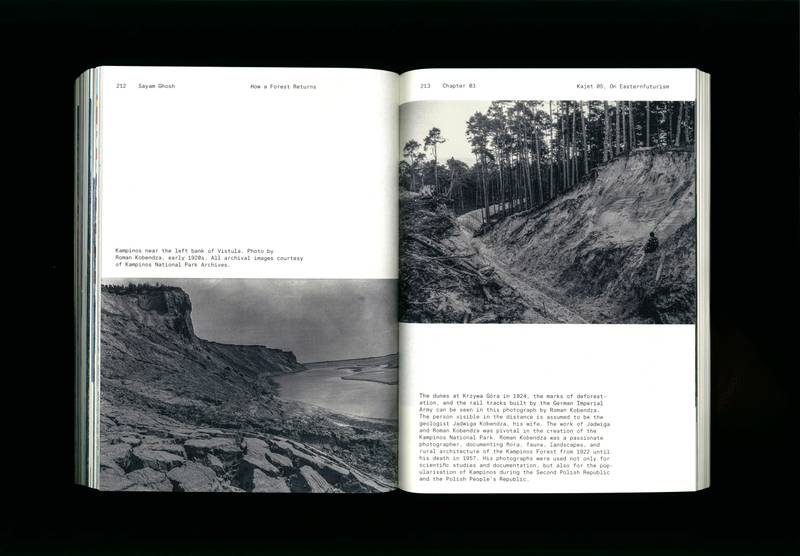

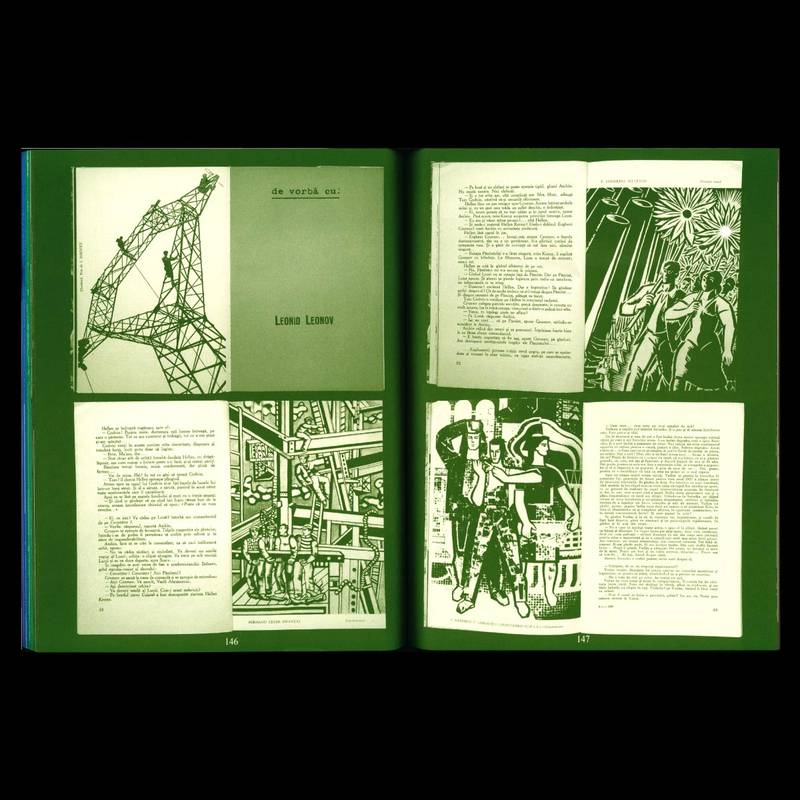

Spread from Kajet 05. Work by Andrei Becheru

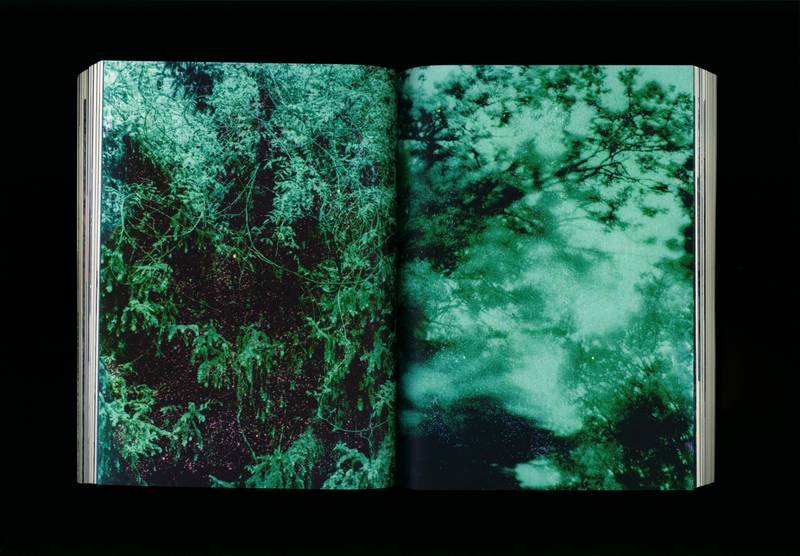

Spread from Kajet 05. Essay by Elena Staicu, photos by Sabin Staicu

M: Let’s backtrack to the concept of Eastern Europe, whose re-articulation is so central to your work. Could you share your thoughts on what makes this region special? What specific conditions make it fruitful for testing out these ideas on rethinking time and futures?

P: I think it is, again, complexity.

We’re dealing with a very complex region that almost seems to refuse a conceptual demarcation in terms of geography or in terms of identity. It lacks homogeneity - it’s not this homogeneous region that people imagine. It is ambiguous; it is disputed … So what is Eastern Europe after all?

I think this is a question that we’re still dealing with. What does Eastern Europeanness mean? What does this ‘Eastern’ stand for under this terminological umbrella that we have come to call Eastern Europe, maybe problematically, I would say.

L: I think it’s perhaps a problematic and overused term. For some, there is this thing called Mitteleuropa or Central Europe, and they refuse to be put in the same bracket as what lies further east. And we always wonder how come Prague is regarded as more Eastern European than Vienna, despite it being situated geographically further westwards.

P: But you could also say, What if Eastern Europe is only a figment of the Cold War imagination? Should we fall into these traps developed by this division? What if this space that was demarcated after the Second World War is nothing less than the result of Western social, cultural and political production of knowledge?

I’m also thinking of this interesting paradox that we call Eastern Europe post-socialist, but in the case of Western Europe, we don’t call it post-feudal. We never apply the same processes of categorization equally.

So, these conceptual, spatial and temporal categories need to be contested. It would be productive to reconsider our own Eastern Europeanness, to move beyond this paradigm of the world carved in binaries—East vs. West—as remnants of the Cold War. But also, maybe we need to move beyond other notions, such as Global North or Global South, in a revised way of talking about global economic differences.

To come back to your question, the East has an interesting ambivalent hybrid position: allegedly too well off to be considered as part of this main idea of the Global South, but at the same time, too weak and too poor to be part of the North. The East is too central and not ‘spectacular’ enough to be truly considered part of the mainstream discourse of otherness.

Only recently do you see this post-colonial or decolonial approach being associated with this region and studies of otherness. Yet, once again, it allegedly lacks the necessary substance to produce so-called absolute value, so-called authentic modifications of culture.

So a key aspect pertaining to Eastern Europe, I would say, is its ambivalence, its hybridity and especially its in-betweenness. It’s this liminal space you can’t really put in a certain category, and because of this, it’s a region in which—and this is true also for our work with the magazine—we will never run out of topics, angles or perspectives. It’s a region that will continue to unfold, and you’ll have to continue unpacking it.

M: It’s also important to say that even within the region, there are different levels of privilege and economic prosperity.

L: Yes, of course.

P: Even the periphery has its own periphery.

M: This reminds me of one of your other texts, ‘Pieces of land in pieces of paper’1, in which you ask, ‘‘How can emptiness be generative, dynamic and rich in a utopian kind of creativity?’’ This word emptiness is interesting here, as it is also how Eastern Europe is often viewed. But it is also misleading because no place is ever really empty. Reapplied to the region, is this seeming emptiness just another shade of its ambiguity?

P: ‘’m thinking of ‘emptiness’ now also as an excuse, in some way.

For instance, Eastern Europe is a region that we try to represent somehow in our work with Kajet, which comes with a certain degree of responsibility. But as we’re living here at the moment, we know that it is lacking certain processes of historicization. And by that, I also mean effective means of writing its own history. So there is a void in how documentation is done, which, of course, doesn’t mean that things are not happening here or that our predecessors lived in this kind of vacuum.

Of course, the official apparatus is outdated; it does not seem to care about citizens, let alone its cultural actors. But we think that it is up to us, those who deal with such matters and live here, to engage in some process of writing the history that happens around us, of documenting it through self-historization. There are other cultural initiatives or artists in the region that adopt similar approaches to archiving precisely because of this apparent emptiness.

M: I would also like to touch upon another aspect of representing Eastern Europe. We spoke about ambiguity, but I also heard you use the phrase ‘post-soviet capitalism’, which is different from ‘capitalism’ in some ways, particularly when it comes to this sense of disappointment and disillusion we feel here.

There were all these dreams of better life that were promised as the curtain fell, and for many, these weren’t delivered. I wonder if you have thoughts on this condition of post-soviet capitalism as a ground for dreaming and hope?

P: We’re definitely dealing with a local, regional variant of neoliberalism or capitalism, which has adapted to the conditions of the region. I’m also thinking of certain assumptions such as cultural delays, this idea that Eastern Europe is always lagging behind, and now, with the defeat of communism, we are back on track with the linearity of history and trying to make up for the lost time of half a century. These are all ideas that come in and dictate how this local version of capitalism is manifesting itself. And I think because of that, we always seem to have this relational dynamic with the West, which I think, at times, can be quite problematic.

Going back to this idea of documenting alternative narratives around us – I think what matters to us the most is doing this with an overt attempt not to succumb to these Western expectations, categories and taxonomies. Maybe because of that, we think that these projects we are doing are necessary. We talked about history earlier, but also art history, and the contemporary art world and the contemporary publishing world, are selective. And archiving itself is inherently selective and tendentious because, ultimately, our history remains, by and large, Western art history.

So, to come up with some kind of response to this attempt to include the East – again, this can be read in two ways - do you want to isolate the East away from the rest, or do you want the East to be part of the same groupings? Not being misled by this recent Western musealization of the East, this process means that the victors, let’s put this in very, again, binary terms - winners and losers – have successfully appropriated the art of the losers. It also means that the so-called Eastern European art is being classified according to Western ideals, estranged from its original context. So I think finding some kind of midway path is possible or needed.

L: Yes, an alternative to these East/West binaries.

M: This made me wonder how it could relate to futures-thinking – could we also build sideways futures then? Futures outside of this linearity?

P: The way I’m trying to come up with an answer to this is that we should struggle against homogenization of knowledge and art production by producing these alternative local knowledges in the plural. So I think besides being sideways, this should also be, always be, in the plural.

L: To include parallel and alternative thoughts and discourses, and practises. Even contradictory narratives that together resemble this reality that we find ourselves in. So, we are able to propose a response to this linear understanding of time and history, present and future.

M: You also work with an archive of Romanian communist printed matter - the Camera Arhiva project. Is this also a way of collecting various alternative histories or experiences for you, or more about archiving the official state-sanctioned printed matter?

P: I think it’s a little bit of both.

L: With this project, once we started doing the research and going through our archives and just finding books in the dumpster and saving them from being thrown out. It’s interesting to see how the printed matter was produced then and that it’s not different from what’s happening now.

For example, they had this take on ecological matters and were already talking about these issues in the 50s and 60s [already].

P: And to go back to your question about futures, the idea with the archive is to give back space to these cancelled ideas or cancelled futures or futures that never came into being. Laura already talked about devalorisation on a very material economic level - that these books are considered worthless now. Of course, some of them do contain propaganda, so there is this kind of tainted layer around them, but it doesn’t mean that everything, every piece of knowledge that was ever produced between 1947 and 1989, is to be ignored.

What we tried to do was reconstruct these alternative worlds, in our case in the publishing world, that have been brushed aside from dominant narratives and discarded from collective memory. The act of archiving does not just mean commemorating the past.

Again, going back to nostalgia, and especially to a form of imagining the future or understanding how people in the past anticipated pre-figured the future. Maybe we can have something to learn from that.

M: There is also something to be said about this discarding of the past. I also see this in my home country very often – this rejection of visuals, material, knowledge or even language from before 1989 - from fashion to furniture or even architecture being torn down or covered by new visual layers.

But, of course, you can’t really erase the past like that. I wish there was more commitment to facing this complexity you talk about—recognising both the propaganda, and simultaneously the value and creativity that could also be part of the cultural production.

L: I also think it’s human nature to discard. I mean, humans have been doing this for a long time. But maybe now we have the possibility of preserving more of the past.

M: Yes, this is true, although I think more so for ‘Western humans’ - coming back to how we conceptualise time, again, this Western conviction that there is nothing to learn from history in a progress-oriented linear timeline, always focused on innovations as if the world was present in a vacuum.

P: Yes, but I would also say the current situation forces us to look for alternatives or maybe to engage in this kind of ‘nostalgic thinking’.

Of course, the archive is not exhaustive, it’s not complete. We like to call it the ‘Archive of Affinities’ – because it’s made out of our affinities, our own personal interests, that are present there. So, it’s a very subjective archive. But I remember finding very interesting titles published on aspects of future-thinking, and I think that the future back then used to have a different usage, at least on the level of discourse.

I would say that now, in post-socialism, late capitalism has reduced the meaning of time into this kind of continuous now, and the objective of capitalism with regards to the prospect of time seems to be that of abolishing it in all its forms.

As citizens of this capitalist world, we stopped thinking about Utopia, about eternity, about the future, we stopped anticipating or making plans for the future because we are living in a dire present. The existence, and also senses of time, have been segmented into mere hours into corporate timetables, Excel spreadsheets, PowerPoint presentations, even self-tracking devices that tend to quantify everything we do. So maybe the conclusion to this is that in the modern time, or the modern age, nobody has time for the future any longer.

L: So how do we revive or create the premises for people around us and for ourselves to start thinking more about our own futures on a collective basis?

Camera Arhiva 26

Camera Arhiva 20

M: It also seems to me that this word ‘utopia’ is quite important and very interesting in the Eastern European context. You talked about how we, in this region, already tried that - supposedly, we have already experienced utopias or have been promised them once, at least. So the word here sounds a bit like a joke – or at least it has a certain ring of an empty promise from the past. Can we reinvigorate it and make it generative again?

P: I think you’re right in the sense that people can get confused with utopia - it’s easy to get distracted talking about utopias in a space that has allegedly experienced one.

So how do we change it from being seen as a relic of the past, a symbol of failure, something that needs to be forgotten? And how do we transform utopia into something that is achievable – which I think by definition is not achievable, but at the same time, I think that was the beauty of utopian thinking before 1989 - this kind of open-endedness, or openness to a possibility. Of course, socialist Romania was not a paradise in any form, that’s not the point I’m trying to make here…

But if we focus on this kind of discursive dimension of state institutions, or how some part of the official culture communicated this idea of progress with the people, which I think today has been mostly connected to innovation and technology.

L: It’s more individualistic today.

P: Yes, and oriented toward profit; how can you profit from progress, rather than how can progress make you a better life?

But progress means open-endedness, right? A kind of mechanism that starts over when the objective is exhausted, when it is achieved. Which I think is precisely fitting to this kind of dialectical understanding of progress – that human progress can only follow in these spirals and not in straight lines, and achieving that utopia may not be the point! It may be – how can we reconnect to share the common goal? Maybe this is the point - to aspire together towards something, to have a societal objective or a common condition, where we change towards the destination, and we may never get there; transformation is not the pathway, transformation is the end in itself that we are looking for.

M: You mention the phrase ‘reconnect with utopia’ – I think this could be unpacked further: this reconnection with utopian possibility, but reconnecting through reclaiming it, bringing a sense of agency and ownership back to utopia. It seems that this Utopia 2.0 needs to be more bottom-up, local, and engaged.

This is perhaps where both utopias and collectivity could be approached critically – they cannot be inscribed from above or imposed institutionally, but there needs to be this belief that living better is possible. And there needs to be both individual and collective commitment to that vision.

P: I totally agree with the bottom-up perspective.

L: And this also applies to what is happening now in the world, and also with the university protests. You could feel that with this individualism approach, people would not come together and stand up for their rights… but I am pretty glad to see that this is happening now and that people have a voice together, even though in some places, it seems it’s very difficult to do.

P: I’m also thinking about this idea of imagination.

There is this premise that neoliberal capitalism is eroding imagination. We talked about time and how it limits our own perspectives and our horizons of possibility. So I’m thinking about how we think of these projects [such as Kajet] as ways of opening up the discussion, but also maybe of collecting various resources that can be used in order to revive this radical imagination.

We talked about this mutant version of post-soviet neoliberal capitalism that keeps on morphing and changing and adapting to the local circumstances. And I think it has succeeded because neoliberalism has this understanding of how to occupy spaces. I think that neoliberalism is very good and very efficient in co-opting dissent. Making dissent, selling dissent. It’s a fine line between – yes, we are dissenting against something, but when does our dissent become commodified? I’m not saying let’s stop revolting against power, but how do we…

L: How do we successfully do that? (laugh)

Image by Pavlo Borshchenko, part of the “Sumy: Sorrow of my days” photo series (2018-2021), the cover of Kajet 05: On Easternfuturism.