Installation view of the exhibition The Terrain Between at Maa-tila Gallery, photo by Uzair Amjad

Saher Sohail is an art history teacher and researcher.

Colonial legacies have for centuries shaped and defined a large part of the modern world. The indelible impacts of our colonial history have led to consequent shifts in identity, if not the erasure of it completely. This, and transcontinental migrations over the past five or six decades, have created diasporas across the world that recall their collective pasts and, in accordance, set the stage for the collective present.

Uzair Amjad’s solo exhibit, titled The Terrain Between at Maa-Tila Project Space, opens up this field of inquiry that recalls the past and reimagines the present through a series of paintings, with the context of colonial history playing a marked role in these definitions. Amjad’s work dialogically engages with the fraught and dualistic nature of history.

This review unpacks closely the images in the exhibit while exploring the subliminal spaces evoked by the works and the voices within history itself. The notion of the subliminal is conjured in Amjad’s quiet works by threading together personal histories and colonial history in a larger context, calling our attention to hidden, often bypassed, realities.

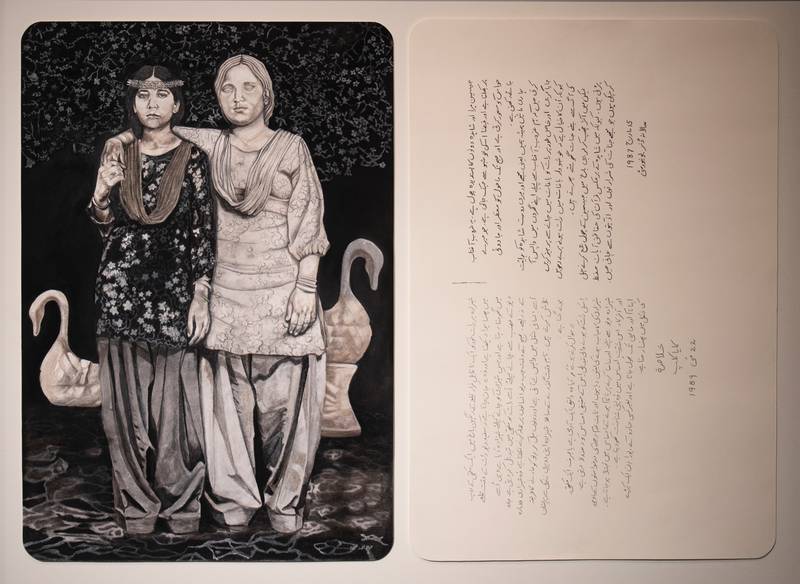

My Mother’s Garden After Sunset, Pastel on paper, 70 x 100 cm, 2024

The exhibit opens with a monochromatic image, an enlarged photograph in appearance, titled My Mother’s Garden After Sunset. Upon closer inspection, the photograph reveals itself to be a painting, but a painting that represents the front and back sides of a photograph. The painting’s formal aspects suggest an element of duality upon a linear reading of this image: Amjad depicts his mother, in black, standing next to her friend, Shahida, dressed in white, flanked by two statuettes of swans in a makeshift photo studio. The backside of the photo painted alongside this image echoes this duplexity, where Amjad shows us his mother’s practice of recording narratives on the back of photographs. The first of two recordings on the back of this particular photograph describes how the artist’s mother would frequent gardens after dark to collect jasmine flowers, and the second summarises a story by Urdu writer Intezar Hussain, titled Metamorphosis1. Following are the two parallel narratives that inform our interpretation of this image, as translated by the artist2:

First note:

Jasmine is both Shahida’s and my favourite flower; it fully blooms at sunset, and its fragrance fills the air and captivates my senses, enchanting my surroundings until dawn. Our mothers always instruct Shahida and me to return home before sunset, emphasising that we should avoid gardens on our way back because Jinn made of smokeless fire wander through fragrant gardens when night falls. However, I often sneak through the garden to collect jasmine flowers for us, as I, unlike Shahida, have memorized the protective verses from the Quran that shield me from the mischief of all demons.

Second note:

Each night, the prince wakes to find himself transformed into a fly, trapped in the vibrant garden of an inescapable fort. He soon realises that a white demon roams the fort after dark, and the princess he came to rescue casts a spell to turn him into a fly, shielding him from the demon’s wrath. At dawn, when the demon departs to wage war on humans, the princess restores him to his human form, and together they search for a way to defeat the demon. However, over time, the prince becomes increasingly troubled by his dual existence, questioning whether he is truly a man or merely a fly. His nightly transformations blur his sense of reality. Despite the princess’s assurances and her pleas to remain steadfast, he becomes consumed by his inability to escape or confront the demon. Eventually, he loses his sense of identity, forgetting his name and past, and begins to remain trapped in his insect form for entire days without any spell being cast upon him.

Both of these notes summon a sensorial experience on two planes—the first connected to the olfactory, with the perfume of jasmine being a distinct memory for most hailing from Punjab. The second pertains to something more spiritual and concealed: the presence of jinns and demons in gardens and the notion of magical transformations, once more a familiar concept to those from Muslim South Asia. The very idea that an ominous, unseen presence can at any moment make itself apparent by touch or vision is enough to unsettle the senses.

Each transcript also offers its own alternative reading of the image, but while the first note, recounting the artist’s mother’s precarious sunset slippages into the garden, supplements the linear reading of the image, I believe the second note does more to unpack the politics of history itself. As Amjad duly notes, this second note also functions as an allegory for the British colonisation of the Indian subcontinent. The image and the narrative itself present a dichotomy, serving as a micro-history within a broader macro-history. Oscillating between realities, this mythical prince, who seems a metaphor for the colonial subject, loses his sense of identity entirely and exists eternally as a creature meant to hide from the “demon”. The story speaks to the idea of subjugation and acceptance in colonial histories and concealment as a tool for adapting to or blending in with newer, perhaps even threatening, surroundings.

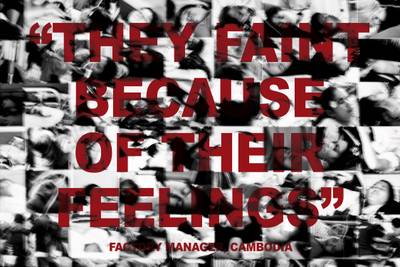

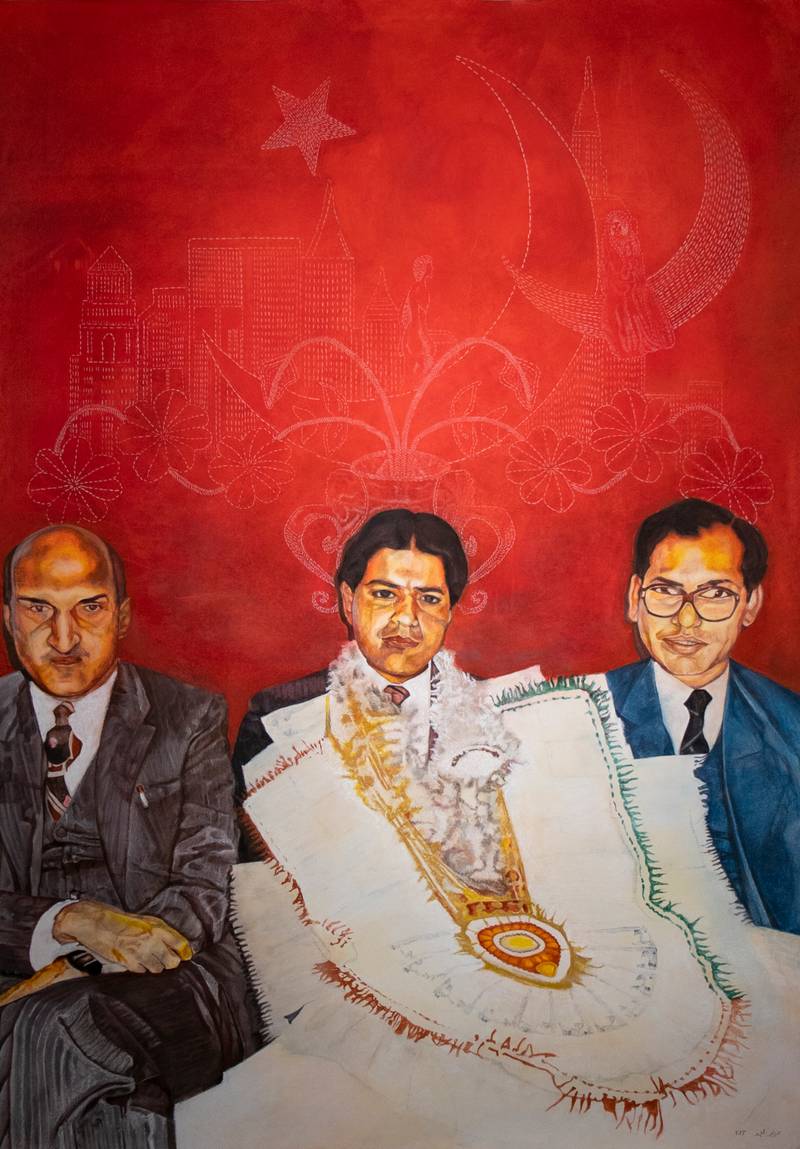

If I Had a Penny for Every Time I Dreamt, Pastel on paper, 70 x 100 cm, 2024

Avtar Brah’s essay Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities3 brings up the political import of proclaiming identity and how the pressing import of recognising and manifesting that identity comes at an early age. Amjad, in his works, seems to proclaim identity as a confounding notion in itself and attempts to grapple with a cohesive realisation of self that does not discount the geographies of his past, or the nuances of history.

One of the works that seems to probe the roots of one’s own sense of self is the work titled, If I Had a Penny for Every Time I Dreamt. Drawn from a photograph of his father on his wedding day sitting between two friends, Amjad shows us the traditional backdrop that the groom was often seated in front of during a typical 80s Pakistani wedding. Ironically, according to the artist’s own research, this backdrop draws inspiration from posters of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) from the 80s, the chosen airline for most Pakistanis of that time to make their resettlements abroad. The image is a comment on the artist’s father’s own looming migration from Sahiwal to Los Angeles after the wedding. The rich crimson background—an auspicious colour at any Pakistani wedding— not only celebrates the match between the bride and groom but also offers a faint glimpse of the promised land. Towering buildings very much factor into the fantasy of the American dream, and are made further desirable to Muslim desi sensibilities with a fecund foreground of blooming flowers, a cascading fountain and the crescent moon – imageries directly associated with paradisiacal bliss.

The groom is wreathed in garlands of five-rupee notes, but the artist has adapted from the idiosyncrasies of the photograph itself and chosen to show only the faded, almost erased, whites of the currency bills. The capitalist promise of plenty that comes out of the background of the image, juxtaposed with the dystopic, near-blank garlands of cash, shows the systemic inequality that underlies most migrations and asks the subliminal question: What were the conditions that propelled these transnational communities to make their migrations? And were hopes of a better life, in fact, fulfilled? Most migrations in earlier decades, driven by these gleaming aspirations, may have been fulfilled to some extent. Rising from middle-class life in Pakistan to middle-class life in the West might have seemed a brighter promise to some, considering the economic difficulties alongside political turmoil in the 1970’s.

Between Palm Trees and All the Kings Coins, Pastel on paper, 56 x 90 cm, 2024

A fragment of the artist’s own childhood spent in Pakistan appears in a painting titled Between Palm Trees and All the King’s Coins. Children costumed as characters from symbols within an Urdu poem are posed in front of a backdrop that reads “خوش آمدید” (translation: welcome). Emblazoned upon the header of the stage are the words “گڈے اورگڑیا کا تماشہ” (translation: the play/theatre of a male and female doll), crowned with an arch of coins from the East India Company. The cast of child actors is sandwiched between statues of Queen Victoria and a beheaded Prince Albert. The painting is laden with marks of imperialist conquest and the colonial mission to define and monetise the Indian sub-continent. The text that appears upon the header of the stage further labels the people of the land itself as mere dolls, perhaps marionettes, to be controlled and steered by colonial powers.

And though colonialism ultimately withdrew its vice-like grip upon the Indian sub-continent, the reigns of the newly formed Pakistan were handed over and over again to powers that saw fit to shape it how they pleased. The presence of palm trees in both the painting and its title, are a nod to the Islamization of Pakistan in the 1980’s under military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq. In tandem with the landscape of the penultimate Muslim state, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Zia’s Pakistan was made to liken itself not only by appearance but also by its legal system, which operates under Shariah law. Saadia Toor in her essay Moral Regulation in a Post-Colonial State: Gender and the Politics of Islamization in Pakistan4, states:

“Overwhelmingly, military regimes in post-colonial Muslim countries have tended to be agents of secularism and modernization: the earlier regime of Ayub Khan in Pakistan, and those of Gamal Abdul Nasser in Egypt and Kemal Ataturk in Turkey are some illustrative examples. Relatively speaking, they have also had the most progressive agenda vis-a`-vis women. Yet, General Zia’s regime was characterized by an explicitly non-secular and violently gendered agenda. The Nizam-i-Mustafa (literally, ‘social order of the Prophet’) promised by General Zia was to be ushered in through a programme of ‘Islamization’, which specifically targeted women’s already limited rights.”

The aforementioned project of Islamisation brought to realisation the Hudood ordinances, a majority of which remain ingrained in the legal system of Pakistan. As Toor states, some of these ordinances famously reduced the rights and agency of women expressly. Perhaps it is only fitting then that the archetypal roles assigned to the children in Amjad’s painting are befitting their gender, according to Zia’s Pakistan. The girls are dressed as blooming flowers, with an underlying message that they are mere vessels of fertility, constrained to a decorative and reproductive role. The boys embody much more dynamic roles in military uniforms, subtly conveying the boasting pride of the پاک فوج (translation: Pak(istani) Army). The double entendre on “pak” is concealed in its other meaning, which is “pure”. This objective of purity is visually and conceptually reinforced with the boy on the far right dressed in the Pakistan flag’s green and white, while the one on the far left wears a crescent moon upon his headband, complete with pure white trousers and shirt. The male gender carries with it the noble mission of progress, paired with purity and the traditional symbols of Islam. Not all is lost, however, in the image. A lone cockerel is perched atop the stage, perhaps as a harbinger of a new dawn and the enlightenment that may come with it. Amjad seems to acknowledge the darkness of a bygone era, as part of collecting fragments of one’s individual history, but also seeks to keep the concept of identity open and unrestricted.

Who Paid the Brass Band of Tobah Tek Singh, Pastel on paper, 48 x 63.5 cm, 2024

Personal histories and collective pasts coalesce once more in this phantasmagoric image titled, Who Paid the Brass Band of Toba Tek Singh? A work that stemmed from aesthetic curiosities, according to Amjad himself, it stands distinctly apart from the others in the exhibit due to its surrealistic setting. Amjad, in our conversation, recounted how his maternal grandfather had to leave behind all of his livestock when migrating from his village in India to Pakistan. His connection to these animals was apparent in his affectionately naming each of them – so the separation was not an easy one, by all counts. Perhaps to honour this relationship between the grandfather and his animals, the artist assigns the central position on the canvas to the humble water buffalo.

The work also borrows from Saadat Hassan Manto’s short story Toba Tek Singh5, which tells the tale of a Sikh man who refuses to leave no man’s land during Partition, as his homeland, Toba Tek Singh, is left behind in Pakistan during the handover. The wound of Partition, and a consequent loss of identity, in South Asian history are inextricably linked with post-colonial trauma, and the brass band that features in the painting is a metaphor for the remains of colonialism. The English introduced the brass band to the colonies as part of their military parades. Post-Partition, the function of the brass band was adapted to performances at weddings, especially in rural areas. In the painting, members of a local brass band ensemble are dispersed in a haveli-like building, with a water buffalo as their only passive audience. The building and its inhabitants levitate into a cerulean sky, symbolic of a no man’s land itself. It also reveals how nations in their post-colonial state, collected remains from the topsoil of colonialism and imbued these with customs from the underlying terrain to form unique traditions.

The Other Side of Love, Pastel on paper, 37 x 63.7 cm, 2025

Back to the Future, Pastel on paper, 38 x 44.5 cm, 2024

The two final images in the display, the former titled, Back to the Future, and the latter, The Other Side of Love, are bound together conceptually in terms of navigating change and coming to terms with all the layers of an individual’s trajectory. In the former painting, Amjad recalls his mother’s habit of creating shrine-like altars of photographs, in their home away from the homeland. Flags of lands that have undergone oppressive regimes and imperialist domination take a central place in the image. The Pakistani flag is hung up playfully by a child toting a toy gun, while the Palestinian flag foreshadows the image on a sticker pasted onto the backside of the phone used to photograph this frame. Children from migrant families are forever at work trying to maintain a balance between their hybrid identities, impacted by domestic and foreign marks of imperialism, and to resolve what it is to be an adult in this subliminal space between two parallel sides of themselves.

The Other Side of Love brings us to the present moment in the artist’s life. It shows a bar-like setting, in which text boxes reveal a conversation between friends. The discussion revolves around love, change, hopes, and dreams. While this discussion unfolds on the inside of the bar, the bartender’s gaze drifts towards a huddled group of three youngsters on the outside, looking in; one of them is wearing a keffiyeh. Once more, the artist draws the viewer’s attention to the plight of Palestinians through an emblem of their state. By invoking such emblems, the artist steers the viewer’s attention towards the modern-day colonial project playing out in Palestine. Such systems of power continue to practice their oppressive regimes under the guise of a supposedly, evenly matched “war”, but the dark history of imperialism foreshadows this entire conflict. Another entire nation and its citizens (those who survive) will once more be scarred by the trauma of a coloniser’s attempts to annihilate and extort yet another land.

The bar’s atmosphere is distinctly inspired by the films of Aki Kaurismäki, the renowned Finnish filmmaker. Known for exploring themes of identity, hope, and a quiet sense of longing, Kaurismäki’s cinematic world deeply influenced Amjad’s work, shaping the bar into a space that reflects his signature dreamlike ambiance. Love, hope and revolution are tied together for Amjad when unpacking Kaurismäki’s films. Indeed, the Urdu word for revolution, انقلاب (“inqilab”), can be etymologically traced back to the word, قلب (“qalb”) which translates as heart. Revolution is an enactment of love, the emotional undertaking of the heart. In that vein, bell hooks[^6] has described love not simply as a noun, but as an action – to do love with intention, so that it may be restorative for individuals, as well as a collective nation.

Contemporary artists from Pakistan have been enmeshed with themes of identity, history, and politics. Be it through the neo-miniature movement and its champion practitioner, Shazia Sikander, whose use of the miniature painting technique is so inextricably linked with South Asian identity, or through composite works like those of Risham Hosain Syed, who often draws on the impact of our colonial history. Uzair Amjad explores these very themes and expounds on them in his quiet, evocative paintings. History, in the work of Amjad, is incomplete without memory and the collection of subliminal voices within the annals of time. Memory is not restricted to the singular phenomenon of evoking nostalgia, but is a significant conduit in Amjad’s work used to help construct and situate oneself in the present moment. This body of work summons a collective past while gathering pieces from the artist’s own identity, revealing the complexity of diaspora. The Terrain Between is a vital exploration of attitudes, behaviours, and voices in the substrata of history that have shaped our collective present. The curation of Amjad’s paintings in the gallery space calls the viewer to journey with the artist as he navigates his way through fond and beautiful memories, shadowed with difficult realities of a colonial past.