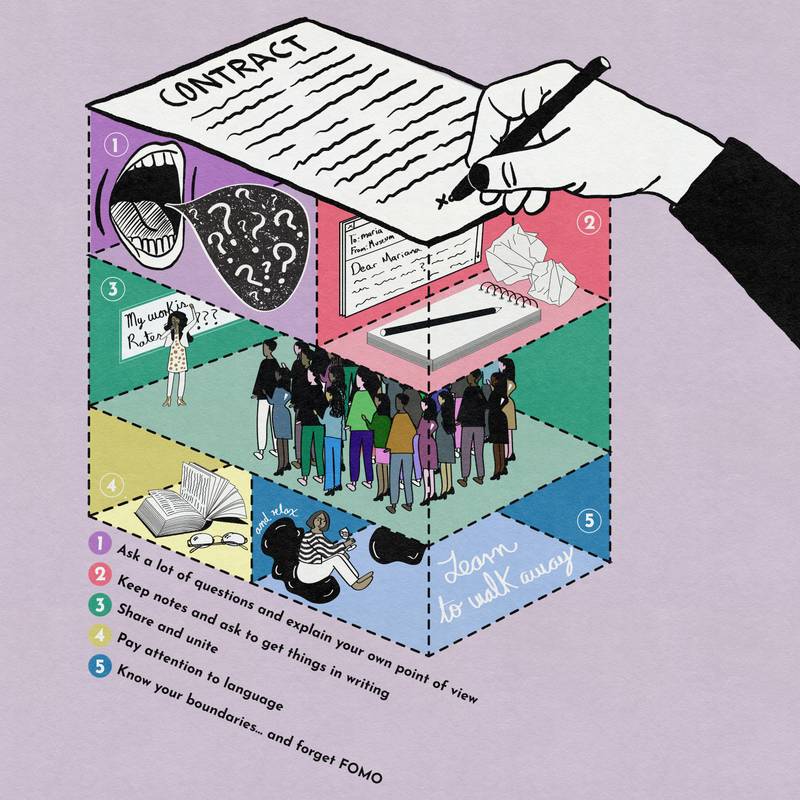

Illustration: Mariana Núñez Sánchez

Riikka Kuoppala is a maker and enabler, artist and legal practitioner, crazy cat and plant lady. Riikka’s one-person law firm Vegan & Legal started as a bike café in 2020 and has since developed into a radical legal practice where sustainability, non-discrimination, and kindness are the driving forces. Her alter ego, the Tax Potato, gives tax advice to artists on Vegan & Legal’s social media channels. One of Riikka’s objectives is to develop alternative strategies for working with legal issues, such as creating feminist agreement and contract writing practices, queer approaches to family and inheritance law, and taxation emancipation for the precariat.

Hey art worker, take care of yourself! <3

As an artist and lawyer-to-be, I often get asked how an artist would ever end up studying law. I would love to say that it was a decision I took after a long and thoughtful process, for some glamorous reason, but like all my major life decisions, it was made on a whim. In my early thirties, I had already burned out big time from working as an artist and was building an exhibition in Kluuvi Gallery (the one near Senate Square, the one that doesn’t exist anymore). Eero Yli-Vakkuri, a friend and fellow artist, was helping me. In fact, it was mostly Eero who built the show while I did some video rendering on my computer. He helped me with that too. I said to myself that it would be nice to have a skill that I could offer in exchange for others’ help. The only thing I could think of was babysitting his children, but how many hours of that would equal the three days of Eero’s professional-level carpentry and construction work? So, I paid Eero some money instead and gave him wine at the opening and we were both happy, but a few months later, when another colleague, Liisa Hilasvuori, mentioned her idea of going to law school (as a joke as it turned out), I said: Brilliant idea! and went on to apply. I only began my studies six years later, however, after several years abroad, when my life seemed to lack direction again. Law school was my rehab. It took many long nights of tedious studies about juridical details, but here I am with a brand new shiny Bachelor of Law degree in my back pocket, pursuing my Master’s, and ready to defend your rights!

There are never enough resources, and unfair agreements can always be defended with a lack of funding since we all know that even the biggest institutions are struggling to exist. I’ve signed a lot of exploitative contracts, ending up working my ass off virtually for free, having texts I wrote published under someone else’s name, and so on. Hardly anything new about all this, but that doesn’t mean it’s right.

It’s hard to talk about art workers and their position in society without thinking of the art world and its particular way of functioning. The artworld is super addictive. Seems like many have a codependent relationship with it. It’s a small bubble that at its best can be incredibly rewarding: you get the freedom of making your own schedules, inspiring discussions with exciting people from all over the world, a space for free thinking and new perspectives, and sometimes it can even be a safe haven for someone who doesn’t fit in elsewhere. Sometimes you really feel the love. But, like all toxic relationships, there’s a downside to being part of it: it is precarious, fundamentally competitive and full of unacknowledged power structures that you are not supposed to care about. How could you not, though? There are never enough resources, and unfair agreements can always be defended with a lack of funding since we all know that even the biggest institutions are struggling to exist. I’ve signed a lot of exploitative contracts, ending up working my ass off virtually for free, having texts I wrote published under someone else’s name, and so on. Hardly anything new about all this, but that doesn’t mean it’s right. Weirdly, the scope of an individual agreement can sometimes go even further than deciding on terms of a particular project and affect the life choices of the people involved—freelancers are often coerced into becoming entrepreneurs because the commissioner of the project refuses to take the responsibilities of an employer, which of course in itself can be a big risk to a small organization in case something goes wrong. And for the freelancer, this obviously means a potential loss of rights for social security, an increase in administrative work, and so on.

There isn’t a lot of mandatory legislation concerning contracts. This means that there aren’t many rules saying what can be agreed and with what conditions, since everyone has a right to make the kind of contracts they want to. Certain types of agreements are regulated by Finnish law1 to protect the weaker party, but an agreement between an artist and an institution, for example, may only be governed by the very general Contracts Act, regardless of how powerful the institution is in comparison to the independent art worker. The main article that regulates the limits in terms of contracts made between so-called equal parties is Section 36 of the Contracts Act, which begins: “If a contract term is unfair or its application would lead to an unfair result, the term may be adjusted or set aside.” This being said, the section is usually applied only to the most extreme cases, because of the freedom of contract. If you think you have been treated unfairly because of the terms of your contract, however, it can sometimes be a good idea to talk to a lawyer. Unions often have free legal services for their members, and the conversations will remain confidential. The lack of mandatory legislation can be a really good thing too, though, since it allows project-specific agreements and experimentation in agreement making. You and your collaborator can decide what you agree on and what your specific needs are in this particular collaboration.

Don’t get me wrong though, I’ve also felt the love. In my case, burning out led to a long process of defining sustainable practices, learning to say no and, from time to time, relapsing. Now that I have made the decision to say that I don’t make art2, I would love to share a few insights about how to make agreements and tackle different collaborations within the arts. Mind you, most of these are not necessarily art-specific, and the list is not exhaustive, but it is very subjective. You can make your own list if you feel like giving the topic some more thought.

- Ask a lot of questions and explain your own point of view

It may seem a little redundant to say that good communication is key in making all agreements, but often we don’t take enough time to consider all aspects of the contract. Make sure you understand every single thing you agree to, and don’t be afraid to open your mouth if there’s something you don’t. Take your time and go through the document as many times as you need to, every chapter, paragraph and subparagraph. The answers to your whys, whats and hows can tell you a lot about how the other party views your collaboration and can reveal points that should perhaps be negotiated further. On the other hand, the other party may not understand your position or needs, if you don’t tell them. Learn nonviolent communication. Sometimes you may be negotiating with someone who is not aware of (or decides to ignore) the power they are exercising over you, and it can be a good thing to voice any perceived inequalities. This goes the other way around too, by the way. Try to be aware of your own position, since privilege is not easy to spot if you’re the one that has it. A good contract process pays equal attention to everyone’s needs. Staying open to communication regarding the details can even clarify what each of you want from the collaboration.

- Keep notes and ask to get things in writing

An oral agreement is legally binding. Yes, true, but if the oral agreement was made between two people with no witnesses, and the other one denies it afterwards, it’s going to be one word against the other and very difficult to prove. It’s always a good idea to have things written down. Save all correspondence (emails, texts, instant messages) of your negotiations, and if you propose something, make your request in writing and ask the other party for confirmation in written form as well. Try to make a signed contract about your plans, so that everything is clear. If for some reason that’s not possible, at least take notes after each conversation in order to have a log. It will be tricky to remember who said what and when, if you need to go back. Asking for a written agreement is not about a lack of trust, it’s about taking your collaboration seriously and wanting to commit.

- Share and unite

One of the main problems in the art world contract-making is the lack of transparency. This has a divide and conquer effect, which often benefits the bigger institutions and has a negative effect on the most vulnerable—the freelancers and the self-employed.

You don’t have to be alone with your contracts. Join a labour union or an artists’ association, talk to colleagues you trust, and share your experiences. Be generous about what you have learned. One of the main problems in the art world contract-making is the lack of transparency. This has a divide and conquer effect, which often benefits the bigger institutions and has a negative effect on the most vulnerable—the freelancers and the self-employed. In particular, emerging art workers often end up accepting unreasonable or even exploitative terms as they have no way of comparing the contracts proposed to them to other agreements for similar projects. The only way to change unfair practices is to refuse to accept them, but you can’t do much on your own. In more demanding situations, it can be helpful to get professional help, even though it’s expensive, especially if the contract is long-term and/or requires you to give up exclusive intellectual property rights, like copyright, and/or a lot of money is involved. Remember that talking to others about a negotiation that is still in process can be harmful, but you can always consult a legal expert and ask for confidentiality.

- Pay attention to language

You know those intimidating contracts where you feel like all your rights are taken away and the other party waives all responsibility, and it’s a bit scary to sign your name? Legal language can seem a bit brutal and complicated even when the intentions are good. Ask yourself if it’s really necessary to write the agreement that way. Besides being legal documents, contracts have a psychological effect on the signing parties. Does the way your document is written encourage your collaboration, mutual trust and a sense that you are making a commitment to a common goal? Sometimes legal terms and long sentences are necessary, but not always, and this is something you can pay attention to when drafting an agreement. You can add chapters about your common goals and aspirations and use encouraging words, for example, in addition to listing the rights and obligations of the parties.

- Know your boundaries… and forget FOMO

Finally, always be ready to walk away. While it is true that something is a common agreement practice in the arts, this does not necessarily mean that the practice is fair or good and should be maintained. Think of what are the things that you are not willing to give up are, and then be clear about those boundaries. There is a sense of urgency related to working in the art world, and it can be a wonderful thing to change the status quo, make things happen, or not to stagnate. However, the sense of urgency sometimes transforms into its evil twin, what I like to call FOMO—the anxiety-creating dread that you can’t say no, because this opportunity will be (for whatever reasons) the one that makes or breaks your career. It probably isn’t! FOMO makes us accept contract terms that we are uncomfortable with. It may feel counterintuitive to walk away from something that from the outside looks like a once in a lifetime opportunity, but it’s never ok to be exploited.