Opening performance of Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture at Nordic Pavilion Biennale di Venezia 2025. L to R: Kid Kokko, Caroline Suinner, Romeo Roxman Gatt, Teo Ala-Ruona

Camille Auer is a media/performance artist, writer and cultural critic from Turku, living in Helsinki for now. She loves the murkiness of hard facts and thinking about queer birds. Currently she wants to premeditate on what would it look like to let things unfold in an unpremeditated way. Camille has had eight solo exhibitions, participated in museum exhibitions and shown work internationally. She has an upcoming exhibition at Sinne gallery and is touring her performance Ruff Knowledge internationally.

niko wearden is a British performance artist who lives in Helsinki now. niko tends to their body in water, lying on the floor, ecological grief and waiting with his kin. he doesn’t want to wait alone anymore. niko is graduating soon from the MA program in Live Art and Performance Studies at the Theatre Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki.

Note: This is a trans critique of trans art. We are a T4T heterosexual couple (camp, right?) living in Helsinki. We are artists and cultural critics. In this text, we use the pronoun ‘we’ while also criticising the use of it. The ‘we’ we write from only includes the two of us, and we agree on the contents of this text. We do not represent ‘the trans community’ nor do we subscribe to the idea that there is such a unified whole consisting of all trans people.

In Spring 2025, it is announced that Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture, a work by Finnish transmasculine artist Teo Ala-Ruona and a working group of 11 people, will be shown at the Nordic Countries’ Pavilion for this year’s edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale. It is to be a huge production, possibly the biggest and most visible instance of Finnish trans art ever. We did not see the work, and thus this text will not claim to be a critique of the work itself. Based on our knowledge of Ala-Ruona’s previous work and what we have seen online, this production most likely contained the most virtuosic of dramaturgies, choreographic language, and august aesthetics. But this we cannot know. What we can address is the online spectacle and political conditions surrounding this work.

We write from absence, the absence of our bodies in Venice and the absence of this work in spaces that would be accessible to us. We are precariously and underemployed trans artists, so a trip to Venice during the biennale is out of reach for us right now, but for most of the world’s trans people, it’s not even comprehensible. It could be easy to dismiss any criticism of work that one has not personally seen1. However, when a work claims to represent a marginalised group, generally a group without any access to seeing it, deeming it not possible to criticise the work from a mediated distance has the effect of granting the right of criticism only to people who are already in those spaces – those implicated in the financial, social and political assets at stake in such a huge production. This is surely mostly wealthy, white, non-disabled, cisgender people.

Ala-Ruona is our friend, and critiquing a friend can be scary. The Finnish art scene is so small that no one dares to criticise anyone because everyone is friends with each other. We end up patting each other on the back, enabling lazy thinking instead of pushing for art that is considered, critical and situated. Trans people must critique trans art because if they don’t, the only critique pushing trans art forward will be borne through the lens of cisness. We fiercely maintain that thoughtful, feminist artistic critique, which we hope this one is, is love, is generous, and is a commitment to a better, more just artistic field.

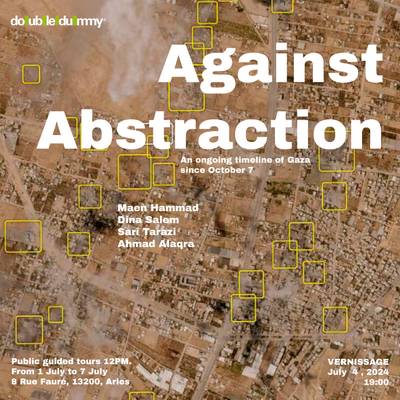

Promotional poster from the Architecture and Design Museum, Helsinki, released in April 2025

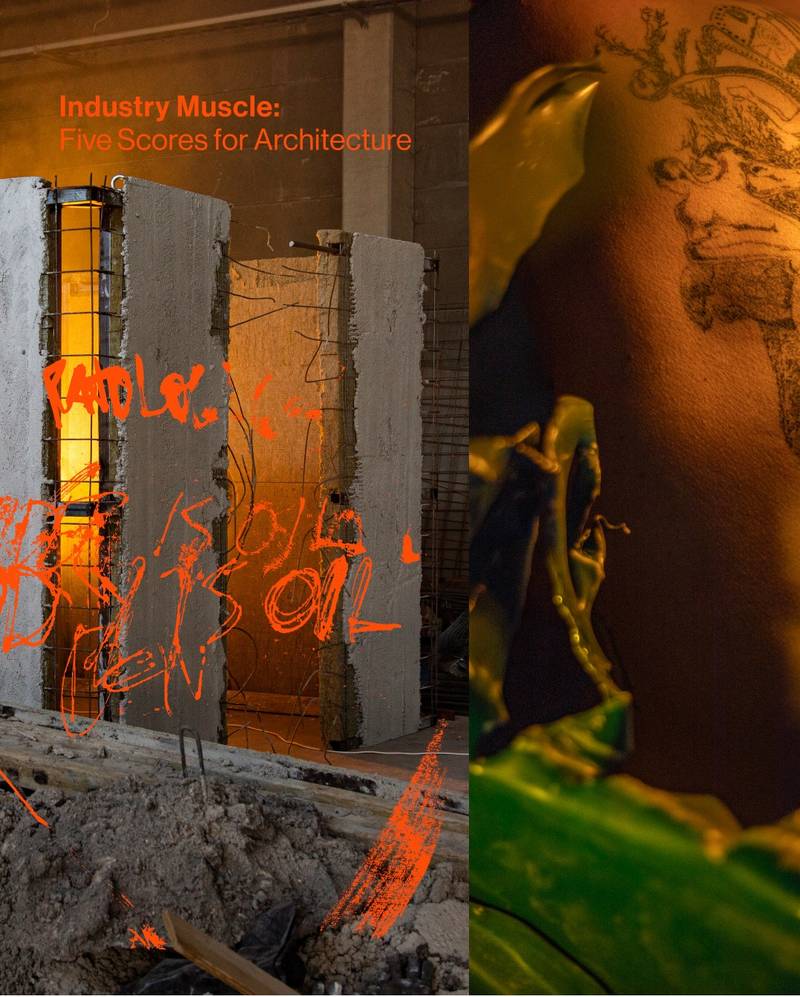

In early spring, when we first encounter Ala-Ruona’s latest work on social media, we see a multitude of posts with a professionally designed look. We see a carefully considered aesthetic of decay and disorder, with rugged concrete and broken glass juxtaposed against tattooed white skin and orange scrawling graffiti-style fragments of slogans, such as ‘body is oil’. In a sleek font, the title of the work is displayed. Captions are concise and informative – professional marketing language. We read how “Industry Muscle examines architecture using the trans body as a lens, establishing a dialogue with Sverre Fehn’s Nordic Countries’ Pavilion, a celebrated example of architectural modernism.” And, we are told, “the audience is invited to observe the Pavilion, as well as architecture more broadly, as a stage for sociopolitical norms that are embedded in fossil-based culture.” (Emphasis ours.)

Using the article ‘the’ does a similar thing as using a universal feminist or trans ‘we’, constructing an imagined unified group of people who share common experiences, struggles or goals.

We reject the tagline of Ala-Ruona’s project. There is no universal ‘the’ trans body. Where does this article ‘the’ come from and what does it do? To us it seems that to look at something through the lens of ‘the trans body’ is claiming to know something that is situated in some imagined universal trans body – ultimately projecting one’s own body as that universal human in the trans context; the same universal human that the work claims to critically dismantle. White, non-disabled, thin, masculine and middle-class.

Using the article ‘the’ does a similar thing as using a universal feminist or trans ‘we’, constructing an imagined unified group of people who share common experiences, struggles or goals. Any idea of a unified ‘we’ as it relates to women has long been critiqued by feminist scholars such as Judith Butler. From here, trans thinkers, including Butler themselves, have long concluded that there is no universal trans person in the same way that there is no universal woman. Trans philosopher Amy Marvin writes in her article Short-circuited trans Care, t4t, and Trans Scenes about her experience of working in a trans-owned community bar, how the supposition of working for ‘the community’ enabled the owners to conduct their business in dubious ways, while rejecting any criticism as ‘divisive’. She references Butler’s critique of a feminist ‘we’, to point out how doing similarly with a trans ‘we’ can be so dangerous. Marvin jibes about referencing Judith Butler in a trans essay in the 2020s – it could be seen as out of date or naive. But it reminds us of violinist and professor of artistic research Mieko Kanno’s work on an ethics of care for the recent past; what and who gets dismissed and rendered as ‘dated’ is often gendered. Marvin writes about how a cohesive ‘we’ can be a way to exclude, how it creates an illusion of tranquil refuge from challenge and bad feeling. In their article, T4T Love-Politics, V. Jo Hsu also writes how an imposed ‘we’ can be used to gloss over harm and to enable disposing of trans people who are seen as divisive. It determines who gets to express themselves as trans and who is omitted. Instead of universality, let’s embrace fragmentation.

As Finland-based trans artists, we have come to know Ala-Ruona’s work well over the years. He is best known for his prolific performance practice; most of his well-known work was produced impressively across a time span of just over five years. His work takes place in a murky and dark underworld beneath contemporary theatre, dance and performance art. What started as a practice of solo performances in tiny galleries has expanded to big international stages including the Performa Biennial in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and numerous other festivals, biennials and venues across Europe and the US in a matter of a few years. The number of performers on stage has grown from one to several. Ala-Ruona continues to make solo works, such as Anabolic Spectacle (2024), and works in collaborations not under only his name, like Babymmalian (2022) with Anni Puolakka and Slit (2023) with Artor Jesus Inkerö.

The aesthetics of Ala-Ruona’s work are very recognisable. His early solo performances, like toxinosexofuturecummings (2019) and My flesh is in tension, and I eat it (2020), had a delightfully home-made feel, despite the virtuosity of the performance’s gestures. They were bursting with a dark, guttural, sexual, painful energy that was spat on the audience in screams and sometimes fake blood, with the performer’s body suspended between ultimate control and something utterly uncontrollable. Since then, starting around Lacuna (2021), whilst the darkness remains, his works have taken on a decidedly more produced and polished appearance. The works with more performers, e.g., Parachorale (2024), include silly and goofy affects and a layer of humour. The work at hand at the Venice Architecture Biennale ups the ante on production values with its designer clothes, massive concrete structures and promo videos that look like slick, shiny Balenciaga ads.

Screenshots from the trailer of Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture

Screenshots from the trailer of Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture

The promo video is directed by Taito Kawata, known for the first Finnish Netflix production Dance Brothers and his commercial work for brands like Stockmann and Lumene. It has a separate working group of 17 people, most of whom seem to be cisgender. The video is set in an industrial hall that seems to have been carefully made to look messy. Two masculine bodies are crawling in a pile of dirt, perhaps trying to claw their way through it. The soundtrack is ultracool techno that creates a detached feeling of a hyper-urban non-space. It has muddled up slogans, repeating while we also see the words on the screen. It asks “who is architecture made for?” and cuts to a sleek tracking shot of two athletic, skinny, white, masculine bodies caressing each other and drawing on each other’s skin on the backseat of a derelict sports car. The camera approaches through a hole in the roof of the car. It is hard not to be cynical about asking such a question as “who is architecture made for?”, and then ostensibly answering it with an image of people with white, masculine, thin, athletic bodies. Okay, they are trans, but do these bodies otherwise actually deviate that much from the norm with which modernist buildings were built with in mind?

A critical understanding of access understands that barriers to access do not emerge only from that which is conventionally understood as disability, but rather processes of disablement, which include, but are not limited to ableism, racism, xenophobia, classism, ageism, misogyny and, of course, transphobia.

‘Who is architecture made for?’ is a question of access and accessibility. Access discourse emerged from the lived, daily, situated realities of disabled people, and has been extensively explored within the fields of critical disability studies and crip theory. A critical review of access understands that barriers to access do not emerge only from that which is conventionally understood as disability, but rather processes of disablement, which include, but are not limited to ableism, racism, xenophobia, classism, ageism, misogyny and, of course, transphobia. A social situation where a trans person gets misgendered or a space that doesn’t have a gender neutral bathroom might not be accessible to a trans person. But that absolutely can not be used to ask the question ‘who is architecture made for?’ in regards to transness in isolation, especially without ethically citing the place from which discourses of accessibility have emerged.

All the shots in the promo video are tracking shots and the camera angles are high; it feels like the point of view is someone looking at the scene from above – a seemingly neutral god’s eye view. It has animated shots of the car being crumpled and of Ala-Ruona’s face falling apart like sheet metal under heavy impact from behind. The other slogans heard and seen on the video are “Have we been misled by the illusion of limitless fossil resources?”, “How do buildings influence our bodies?” and interestingly, with the last one, the audio says “Can the trans body guide us as we rebuild our thinking?” while the text on the screen has the word “body” replaced with the word “experience”. If this is an attempt to divert from the problematics of talking about “the trans body”, it does not help and waters down what power was in the snappy, material feel of “the trans body”. The problem is not talking about the body, it’s in claiming there to be a universal body. “The trans experience”, rather than “body”, moves the implied universality from the corporeality of bodies to the abstraction of gender as an “experience”. We are concerned that this leaves space for the transphobic notion that trans people only exist on some non-material mental plane, attacking the reality that trans people even exist.

Installation view of the Nordic Pavilion Biennale di Venezia 2025. Photo: © Ugo Carmeni

The work itself includes set design by Teo Paaer that is open to audiences as an exhibition throughout the biennale, a performance on the opening weekend, a video and an essay. The exhibition consists of the derelict sports car we saw in the video, which appears to be the same car that was used in Ala-Ruona’s Enter Exude (2023), penetrated by two concrete beams, holding up another slab of concrete. There is a massive, rectangular, shelter-like structure which appears to be made of steel-reinforced rugged concrete, contrasted with shiny, even steel plates on the inside walls. The exhibition also features a two-channel video installation made by Venla Helenius, of which there is no material online that we are aware of. On the glass facade of the pavilion graphic designer Kiia Beilinson has spray-painted with a thick, drippy orange line the word Bodytopia.

On the opening weekend there is the performance, with Ala-Ruona taking the stage with Kid Kokko, Caroline Suinner and Romeo Roxman Gatt. They are dressed in costumes by designer Ervin Latimer – loose trousers and shirts in orange and grey, with hints of stripes that make them resemble prison uniforms. In videos on Instagram, we see the masculine performers holding each others’ head, locked in tension, or taking on a wrestling match surrounded by rich people sipping their complimentary drinks in outfits that cost enough to sustain several trans women for a year. Watching all of this on our screens, it feels difficult to comprehend that this really could be a work for trans people. It feels so disconnected from the daily, material realities of the vast majority of trans life. The gestures do have a powerful, homoerotic affect but their relationship to architecture remains unclear. Ala-Ruona’s work often has this trans-homoerotic aesthetic, which we are excited by, but it is never spoken about in information about the work.

Opening performance of Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture at Nordic Pavilion Biennale di Venezia 2025. L to R: Caroline Suinner, Romeo Roxman Gatt, Teo Ala-Ruona, Kid Kokko. Photo: Venla Helenius

Ala-Ruona’s essay Bodytopian Architecture, written in dialogue with architect A.L. Hu, describes in detail the five performance scores of the work. In Ala-Ruona’s words, scores are “a central tool in the field of performance art […] guidelines for experimentation, the performer’s own interpretation, improvisation and exploration.” He describes in his essay how “sometimes a score contains step-by-step actions, rules or prompts for the performers, and sometimes it can be very open-ended or poetic.”. In the introduction of this same essay, Ala-Ruona writes that he will metaphorically destroy the pavilion and “deconstruct the mental framework and status of the pavilion in modern architecture”. Sounds like quite an undertaking.

During the opening weekend of the Venice Biennale, still at home in Helsinki, we attend a public conversation at Museum of Impossible Forms, between Mia Wennerstrand, a Finnish artist with an interest in the histories of EU and Nato and their political ramifications, and Nat Raha, an Edinburgh based activist-scholar, focussing on transfeminism, LGBTQ+ genders and sexualities and practices and collectives of care and social reproduction. Raha is also one of the writers of the book Trans Femme Futures, which this talk specifically attends to. Raha talks about how we can be as critical of governments and power structures as we want, but it will not change anything, and we will remain complicit in the power structures we exist in. She says that we need to situate ourselves in that complicity and negotiate little spaces of community. We all make strategic alliances with power, but what matters is how we actually shift power down or build it from the ground up. Who wouldn’t say yes to making a work for the Venice Biennale, even if there wasn’t enough time to make it really considered? Working commercially, like Kawata, to pay the bills isn’t necessarily a terrible thing to do either. When you use real-life political struggles as an aesthetic to advance your own career or sell a product, that is where the trouble begins.

What does it really do for trans people to be ‘included’ in Venice? Trans people do not need inclusion; we need liberation. Creating an illusion of inclusion serves to legitimise the institution without doing any actual work towards the liberation of marginalised people.

Institutions want to maintain themselves, grow and be financially viable. People working for institutions are vested in their institutions’ continuous existence. The critic duo The White Pube write about what they call ‘Level One Identity Art’; art that is based solely on the artist describing their marginalised identity and what it is like to live in the world with that identity. In degree shows and independent venues, that might be harmless and a necessary phase in people’s artistic practices, but when it gets staged in big institutional settings, it runs the risk of commodifying actual sociopolitical processes of subjugation to the profit of the institutions. Ala-Ruona’s work is not Level One Identity Art, and his political aspirations appear sincere. However, his work represents the Nordic Countries at the biggest architecture exhibition in the world, and does speak emphatically to a trans experience, we believe, without enough critical situatedness. It runs a high risk of feeding into a nationalist propaganda that the Nordic countries are so rehearsed at perpetuating – one of human rights paradises, havens of inclusivity and ‘happiest countries in the world’, where trans people live freely, luxuriating in well-paid artistic opportunities and being celebrated on international stages. What does it really do for trans people to be ‘included’ in Venice? Trans people do not need inclusion; we need liberation. Creating an illusion of inclusion serves to legitimise the institution without doing any actual work towards the liberation of marginalised people. Undoing this reality is, of course, not the sole responsibility of Ala-Ruona. We are making here a wider structural critique – one we think must be considered when looking at artworks shown in such nationalist contexts.

During the talk at Museum of Impossible Forms, we heard Raha talk about femme labour in contrast to masc energy. According to her, the masc way would be to just drop a fully formed vision of the world onto people, functionally saying ‘I’ll do this for you, I’ll fix it’, while the femme way would be to ask ‘how do we create an environment where we can do this together?’. For her, femme responses are curiosity, attentiveness and supporting each other’s visions and activities. Femme labour is every day acts of care; femme becomes an offer, an atmosphere. These categories should not be essentialised, as in, only femme people can and should do this feminised labour. We feel that Ala-Ruona’s grandiose words about conceptually destroying the Pavilion and dismantling modernist thinking feel like a prime example of the masculine energy Raha describes. We wonder what this work could be if it would begin with Raha’s definition of femme labour. Raha stresses that these liberatory practices come from Black and brown communities. Returning to V. Jo Hsu’s T4T Love-Politics, they write that white trans people benefit from the work of Black trans women, while the material needs of Black trans women remain unaddressed. We ask, who does this work claim to be for, who does it really serve and whose labour is it borne out of? Just saying ‘Black trans women are the most marginalised trans people’ in isolation from any action doesn’t actually do anything towards Black trans liberation.

After the public discussion, we chat with Wennerstrand, amongst other things, half-jokingly about the balance of mascs to femmes in the trans people in the audience. It is close to equal, whilst usually at Helsinki trans events the ratio is heavily skewed towards a dominance of transmasculine people and a notable absence of femmes. niko offers an explanation – “all the boys are in Venice”.

A possible counterpoint to this is to consider that large-scale representation, even if imperfect, might still offer visibility or strategic value. But trans people know all too well that visibility without protection is a trap.

Ala-Ruona writes about fossil fuel and the infrastructure surrounding it that are needed to sustain the illusion of purity and cleanliness that modernism is known for, and how deviating from the purity of cis hegemony can challenge the ideals of purity elsewhere too. Nicholas Tyler Reich writes in Truck Sluts, Petrosexual Countrysides, and Trashy Environmentalisms, that the climate crisis is a cis issue and there might be trans solutions to it. We think the climate crisis does need to be approached from different angles with different tactics, but we struggled to understand from the material online and by reading Ala-Ruona’s accompanying essay how exactly the transness he proposes does grapple with the climate emergency. Does the vision of transness he offers really deconstruct modernist petro-capitalism or merely represent or recreate it? He criticises the energy-expenditure required to upkeep the illusion of purity in modernist architecture, while creating aesthetics that are in so many ways pure and polished, even when they are made to look messy. The processes of making the work look the way it does requires heavy expenditure of energy in forms of labour and moving people and materials. The contradiction between stated political goals and the way to reach them can also be an interesting one, and asserting that one can not criticise what one takes part in is a false premise, since, as Nat Raha’s talk reminds us, we are all complicit. Perhaps Ala-Ruona’s critique of petromodernism and capitalism would be stronger if he affirmed and situated his own masculine fascination with it – fast cars and concrete architecture.

Installation view of the Nordic Pavilion Biennale di Venezia 2025. Photo: © Ugo Carmeni

Trans issues do not exist in a vacuum. They are intricately entwined with racial justice, class struggle and processes of disablement, which are all realities that intersect with the manifold urgencies of climate change. Approaching broad questions, such as “who is architecture made for?” and “have we been misled by the illusion of limitless fossil resources?” from an isolated, but still unspecified point of view of ‘transness’ is reductive at best, and harmful at worst. Ala-Ruona and the curator of the project, Kaisa Karvinen, have made statements about how the project wants to start conversations about human rights and specifically trans rights. Ala-Ruona has pointed out in numerous interviews that trans women’s rights are the most targeted globally. Again, does pointing this out really do anything for trans women? Whilst trans people across the globe face the most extreme attacks on their right to exist, are any of us really thinking ‘but at least we are represented, included, at the Venice Architecture Biennale?’? The work claims to be for us, but as niko’s British trans siblings call them and cry because they have had their estrogen prescription taken away, would it really be of any comfort to hear, ‘my trans friend is representing the Nordic Countries in Venice’? A possible counterpoint to this is to consider that large-scale representation, even if imperfect, might still offer visibility or strategic value. But trans people know all too well that visibility without protection is a trap. As awareness of trans people has grown amongst global public consciousness, so has the backlash against our protections. Trans people with large public platforms such as this one have a particular duty to use it responsibly and consider the possible negative implications, as well as the positive ones, of representing a marginalised group on such a stage.

Ala-Ruona’s work speaks to a very specific trans experience, a sexy, homoerotic, beautiful, important and urgent one, but only one. He really is one of the most privileged trans people in the world (as are we), and mobilising any kind of universality of trans marginalisation towards an abstruse critique of fossil fuel culture and modernist architecture does feel difficult to swallow when the daily urgencies of some of us are just so very different and beyond what can be known by those of us who do not share the same experiences. Trans people are being bombed in Gaza and Iran, denied access to healthcare in places it has long been securely available, denied entry at borders, forced to undergo conversion therapy, and generally facing all kinds of horrors in this world, relating and not relating to being trans. We only know what it is like to experience what we have personally experienced. This critique is first and foremost a request for a situatedness, get rid of the ‘the’ and the ‘we’, and start to talk from a place of what you really do know, rehearse and live. Only from this fragmented place that acknowledges that all trans experiences are hyperspecific and intersectional can we claim to be committed to trans liberation.