Still from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then – Deekshabhoomi, a significant Buddhist pilgrimage site in Nagpur, India, where Dr. B. R. Ambedkar and over 500,000 followers embraced Buddhism on October 14, 1956. The event is commemorated annually on Dhamma Chakra Pravartan Din (Ashok Vijaya Dashmi)

Dr. Swati Kamble is an anti-caste, intersectional feminist activist and researcher studying women’s mobilisation, activism, and social movements. Her work focuses on understanding what drives marginalised, oppressed caste women to organise and advocate for their rights despite facing systemic caste and patriarchal backlash.

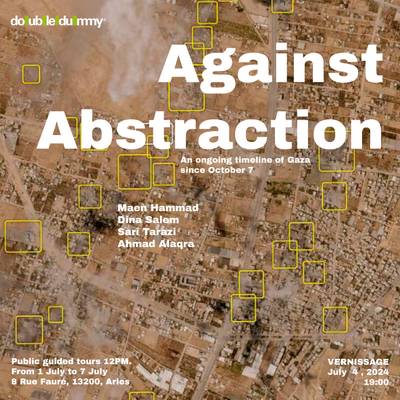

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then | Directed by Jyoti Nisha | Duration: 111 minutes | Language: Hindi, English | 2023

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then (BRANT) opens with an arresting admission, “The film is not working for me.” This refusal is generative. It signals a commitment to delve deeper into the correlation between caste and popular culture, engaging in a critical exploration of the popular media landscape that routinely ignores, misrepresents, and silences Bahujan narratives. From that point on, we see a dialectic that Jyoti Nisha, the film’s director, holds with herself and with the experts she interviews, as well as the stories and significant events in the anti-caste movement and political history she showcases in her film. The director’s choice to feature in the documentary as one of its protagonists demonstrates her refusal to remain the invisible ‘spectator,’ the so-called ‘objective’ authority who enters the ‘untouched’ lives of the Bahujan to ‘discover their truth.’ Instead, she takes ownership of the narrative; she is part of it, she is her people. This standpoint is profoundly emancipatory.

As an academic, researcher and anti-caste feminist activist myself, I recognise and relate to the need for this project. While a growing body of scholarship by Bahujan researchers has been challenging the status quo, the structural and representational limitations in popular media and cinema, which Jyoti Nisha highlights in her documentary, remain entrenched in academic spaces. In the academic world, much like in popular media representations, the lives and narratives of Dalit-Bahujans have long been absent. When acknowledged, these references to works by Bahujan intellectuals are typically cited in a performative manner by savarna academics. Researching caste becomes synonymous with researching the lives of the Bahujan, as though the savarna are casteless and their role in caste maintenance is not necessary to study caste. Gopal Guru (2002)1 captures this asymmetry through the metaphor of the “theoretical Brahmin” and the “empirical Shudra,” where the savarna scholars retain the authority to theorize while relegating Bahujan marginalised scholars to producing data about their communities. As Guru writes, “It is not that the Dalit-Bahujan lacks the ability to theorize, but the social sciences have not granted legitimacy to theory emerging from subaltern subjectivity.” (Guru, 2002). This entrenched epistemic hierarchy denies Bahujan scholars the space and authority to shape knowledge on their terms.

Research produced about caste and the lives of Dalit-Bahujan in India and Western institutions continues to be dominated by savarna and White scholars who position themselves as authorities on Bahujan lives, often exercising control over which stories are told and which forms of knowledge are deemed legitimate, leading to appropriation and epistemic violence.

In my article “How the Savarna Makers of Made in Heaven2 Failed to Build Ethical Collaboration” (The Wire, 2023), I critique how upper-caste, upper-class filmmakers appropriate stories of caste-oppressed communities without engaging in ethical collaborative practices with the communities whose lives and struggles they try to portray on screen. This lack of accountability not only results in extractive storytelling but also reinforces existing caste hierarchies within the realm of cultural production.

Bahujan narratives in media and popular culture are invariably mitigated through a savarna gaze that disregards Bahujans as people with agency, complexity, and vibrant histories of resistance. In such a milieu, Jyoti Nisha undertakes the immense and multifaceted task of unpacking the historical denial of Bahujan stories in media and popular culture, interrogating how history and mythology collude with contemporary violence. She insists on telling her story and choosing her representations, pushing back against appropriation and distortion. Exemplifying Bahujan-centred authorship, which is both politically grounded and ethically conscious, this documentary resists the savarna gaze not only in content but also through its mode of production, offering a model of narrative sovereignty that challenges savarna appropriation in Indian cinema. It critiques popular culture’s “victim gaze.”

Still from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then – Jyoti Nisha introduces herself and shares her intentions for making the film

Dalit-Bahujan women, who are at the forefront of the movement and resistance, often face the most brutal forms of violence. The documentary explores how the intersection of caste and gender shapes the lived experiences of Dalit-Bahujan women. Through a story of her mother, the director gives us a glimpse of why this intersection is personal to her. As a young girl, Jyoti Nisha’s mother was harassed at school by upper-caste boys; she hurled a stone at them in retaliation – an act of resistance that resulted in her father discontinuing her schooling for fear of real, imminent danger of caste atrocity. This personal history leads Jyoti Nisha to ask, through her documentary, who is a “good” or a “bad” woman? And whose stories matter? These questions are raised to shatter savarna judgments on Bahujan women. The documentary interweaves these inquiries with the director’s journey of self-discovery and awakening to her social and political identity.

In one of the early scenes, we see Jyoti Nisha pacing restlessly, amidst words such as “eyewitness,” “memory,” “popular culture,” “feminism,” and “ways of seeing.” In the next scene, we see her meditate, through the chants Buddham Sharanam Gachhami, Dhammam Sharanam Gachhami, Sangham Sharanam Gachhami (I take refuge in Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha), while her spirit is portrayed as a running body as though grappling for answers. The scenes tie personal introspection to Ambedkarite Buddhist principles, which connect spirituality with resistance and the self with the community. It’s a journey toward self-respect and building a community that fosters the ethos of Bahujan hitay, Bahujan sukhay (for the welfare of the many, for the happiness of the many). Jyoti Nisha then travels to Chaityabhoomi in Mumbai, the final resting place of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, lovingly known as Babasaheb, as if to seek clarity on why she has embarked on this journey. From this emancipatory location, the documentary takes us on an intellectually vibrant journey to understand why Bahujan stories remain absent from mainstream media.

Stills from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then

Jyoti Nisha introduces the concept of “Bahujan spectatorship”3 (Nisha, 2020), a term she coined in her 2020 research article, to describe an oppositional and political way of watching media and cinema – one that actively rejects Brahminical representations and seeks to tell stories from the perspective of assertion from a non-Brahmanical gaze, imagination and lived experiences. Her research exposes the representational violence inherent in dominant media narratives and also illustrates how Bahujans are increasingly reclaiming agency over their stories and cultural production. This is evident in her intervention through the making of the documentary and in her contributions to other significant projects, such as assisting filmmaker Neeraj Ghaywan (2021) on the short film Geeli Pucchi, which compellingly explores the intersections of caste and gender through a narrative of inter-caste queer love.

In the striking animated retelling of the Ekalavya-Dronacharya story, Jyoti Nisha subverts Ekalavya’s response to Gurudakshina, who raises his middle finger to Dronacharya instead of acceding. This radical gesture presented in the documentary serves as a visual metaphor for Bahujan resistance, reclaiming agency in narrative-making.

The documentary effectively uses autoethnography as its narrative mode, presenting the director’s reflections and introspections as a monologue that guides the viewer through her sense-making process. From this reflexive standpoint, the documentary embarks on an intellectually rich and thought-provoking exploration of the structural erasure of Bahujan voices from mainstream media. It compellingly traces a continuum between the symbolic and cultural violence embedded in ancient Hindu mythology and the ongoing realities of caste-based oppression. Hindu mythologies, such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, glorify acts of violence by Brahmin and Kshatriya figures as necessary for maintaining a hierarchical social order. One example is the oft-retold story of Ekalavya and Dronacharya in the Mahabharata, attributed to Ved Vyasa. In Vyasa’s version, Ekalvya, an Indigenous Nishad prince and gifted archer, is deceitfully coerced by Dronacharya, a Brahmin guru to the Kshatriya Pandavas, into severing his thumb as Gurudakshina, which he calls Eklavya’s great act of devotion to the guru. This act ensures that Ekalavya, situated outside the upper-caste varna order, does not surpass the martial prowess of the Kshatriya elite.

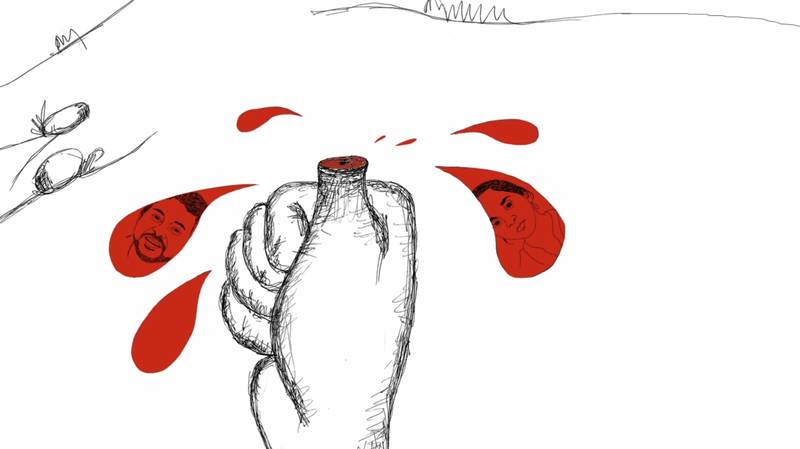

Still from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then – visually links the historical injustice against Eklavya to the contemporary tragedies of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi, whose faces appear in the blood drops from a severed thumb

In the striking animated retelling of the Ekalavya-Dronacharya story, Jyoti Nisha subverts Ekalavya’s response to Gurudakshina, who raises his middle finger to Dronacharya instead of acceding. This radical gesture presented in the documentary serves as a visual metaphor for Bahujan resistance, reclaiming agency in narrative-making. Foregrounding such narratives reveals how these mythologies not only reflect but also reinforce contemporary institutionalised caste violence, thus offering a potent critique of how cultural texts have long been mobilised to legitimise exclusion and uphold dominant caste hierarchies. In the animated scene where Eklavya’s thumb is cut, the blooddrops show the faces of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi.4 This is a significant scene in the context of historical power dynamics, where oppressed caste communities were subjected to brutal punishments for transgressing caste norms. Hindu scriptures and law books like the Manusmriti prescribed pouring molten lead into the ears of oppressed caste individuals who dared to listen to sacred texts. The cutting of Ekalavya’s thumb functions as a symbolic punishment to preserve power in the hands of the savarna. Therefore, this subversive reinterpretation provides a vivid analogy to the resistance led by oppressed caste students in university spaces, as they fight for their right to education, as well as other regional self-respect movements that the documentary captures. The animated sequence is not merely a reimagination but a recasting of history, an assertion of defiance against oppressive structures. This moment demonstrates how dominant narratives can be subverted and transformed into tools of emancipation.

The documentary transitions from this reimagining of the Ekalavya-Dronacharya story to the lived realities of contemporary institutional violence, particularly the searing moment of Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder in 2016, which sparked a historic wave of Ambedkarite student activism. Born in 1989, Rohith Vemula was a PhD scholar at the University of Hyderabad and an active member of the Ambedkar Students Association (ASA). The underlying tension at Hyderabad University had been escalating since the previous year, marked by persistent clashes between the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) – the student wing of the BJP and the ASA over various contentious issues. While such campus agitations are a common feature of Indian student politics, the situation took a significant turn in August 2015 when Susheel Kumar, an ABVP leader, publicly labelled ASA students, including Rohith Vemula, as ‘goons’ in a Facebook post, specifically in response to their protest against Yakub Memon’s hanging. After Cabinet Minister Bandaru Dattathreya requested action against Rohith and his friends, Human Resource Development (HRD) Minister Smriti Irani sent letters to the University of Hyderabad demanding their suspension. As a result, Rohith’s suspension, which had previously been revoked, was reinstated. This episode occurred despite the police dropping charges against Rohith and the discovery that accusations against him were forged. As a direct consequence of this disciplinary action, Rohith and his friends faced “social boycott” from campus accommodation, and the university further compounded their hardship by halting the payment of his monthly fellowship of Rs. 25,000.

In the documentation of Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder in the documentary, we see the recounting of how the student members of ASA at the Hyderabad Central University, including Rohith, were ostracised, barred from the university, and not allowed to enter their dorms, nor were they allowed to access the university mess (canteen). The suspended ASA students positioned themselves outside the university gate and named their protest site “velivada,” which refers to an untouchable dwelling located outside a village, symbolising the presence of casteism within the university environment. Jyoti Nisha ties this ostracisation to Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s story about how he was thrown out of the Farsi inn in Baroda when the neighbours found out about his caste identity.

The use of animation is particularly effective. Animators Harikrishnan Sasindran & Mriganka Bora skillfully bring the director’s vision to life, while Sunil Awachar’s rigorous illustrations add depth and intensity, resulting in a visually compelling experience. Various animations, such as the story of Ekalvya and Dronacharya and Jyoti Nisha’s mother’s story, feature voiceovers that are deliberate in conveying the message of how entrenched caste is, but also how resistance and resilience are innate to the Bahujan.

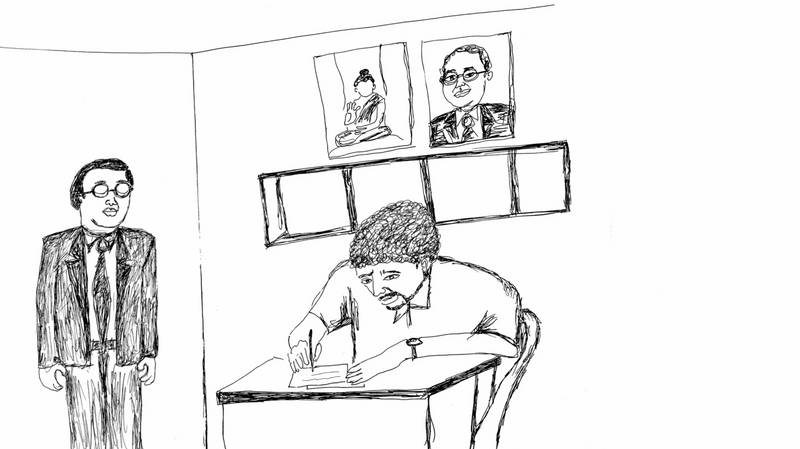

Another animation depicts Babasaheb walking towards Rohith, who appears to be writing his final letter. From a Dalit Bahujan lens, this viewing of Babasaheb and Rohith coming together invokes a catharsis. Rohith Vemula, a young researcher who dreamed of becoming a writer like Carl Sagan, had written a letter before ending his life in which he describes all the possibilities that lay before him. This letter charged the student movement across India. Babasaheb’s reach for Rohith symbolises the connection between the past and present, embodying the pain and resistance it sparked.

In an animated scene, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar (Babasaheb) approaches Rohith Vemula as he pens his last letter

What followed Rohith’s institutional murder, politically, is documented through various witnesses and experts who acknowledge how hostile the university spaces are. The documentary poignantly highlights the unique personal and political experiences of Bahujan individuals. Viewers understand how deeply ingrained and politically charged casteism is in various institutions in India. As former UGC Chairman Sukhadev Thorat points out, students are urgently calling for the Rohith Act to address student discrimination comprehensively, yet no action is being taken in this direction. This proposed bill (Prevention of Exclusion or Injustice) (Right to Education and Dignity) Bill, named in honour of Rohith Vemula, would establish vital protections: it includes provisions for providing compensation of up to Rs. 1 lakh to students who face caste-based discrimination in higher education institutions and stipulates that persons guilty of discriminating against SC, ST, OBC and minority students will face a jail term of one year and a fine of Rs. 10,000.

Still from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then – Radhika Vemula leading a protest march during Dalit Asmita Yatra

Babasaheb instilled in his masses a transformative message of constitutional morality, urging people to uphold their rights even in the face of violence. It is this very teaching that we see manifested in Radhika Vemula, mother of Rohith Vemula, addressing a crowd of thousands, telling them that the constitution has given us rights, and to follow the footsteps of Babasaheb and educate our children.

In the same year as Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder, we see Bahujan leader and now Member of the Gujarat Legislative Assembly, Jignesh Mevani, in Gujarat leading widespread protests following the dehumanising public flogging of seven Dalit men in Una. Mevani gives a rousing speech at a mass rally, rejecting dehumanizing caste-based occupations like manual scavenging and declaring to the leaders of the government, “Keep the tail of the cow to yourself, give us our land!” Mevani reflects on the challenges when it comes to discrimination and violence committed by non-Dalits against Dalits. He says that there needs to be work done to raise the consciousness of the non-Dalits. He also gives a critical commentary on the limitations of the identity politics of the Dalit Bahujan. He states that the most pressing issues of education, land reforms and gainful and dignified employment for the Dalits get sidelined due to identity politics. This viewpoint highlights the diversity of ideas on emancipation within the Bahujan leadership and their differing standpoints, reflecting the varying political and social consciousness of Bahujans in different regional contexts.

Supporters of the Jai Bhim Army gathered at a public address in Delhi.

Bearing witness to upper-caste violence, a Bahujan woman protests the desecration of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s statue in Saharanpur

Varied approaches to liberation through the annihilation of caste illustrate how individuals, driven by a quest for self-respect and dignity, often choose to fundamentally reject oppressive caste structures. Driven by this quest, families of the young men brutally beaten in Una reject the caste-based occupation of clearing dead carcasses and also convert to Buddhism. This act of conversion embodies a theory propounded by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar: ‘Revolution and Counter-Revolution.’ As Babasaheb himself asserted, “if you want to establish equality in the society and acquire erudition, then you should adopt and espouse Buddhism.” This highlights religious conversion as one profound pathway to caste emancipation, alongside political activism, economic demands for land and employment, and the broader assertion of dignity and rights.

Clocking in at nearly two hours, this feature-length documentary is ambitious and expansive, generous in its scope, as it covers many complexities and facets of the Bahujan identity. It is a necessary intervention at a time when Ambedkar’s name is invoked tokenistically for political appropriation. Important historical events are interwoven with present-day realities in a way that illuminates both the persistence of casteist narratives and the longstanding resistance.

From here, the documentary takes us to Saharanpur, where we hear a daring call of a Bahujan woman, a survivor of upper caste violence who had protested the defilement of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s statue rings loud: She roars “We will die for our Babasaheb; he should not be dishonoured.” The Bhim Army, led by Chandrashekhar Azad, becomes another focal point in this emerging history of assertion, dignity, and the personification of social consciousness that identity politics bring about. Each of these events is intricately tied to the broader ideological and historical thread of the anti-caste movement across the country.

The documentary is rigorous in its research and generous in its storytelling. Clocking in at nearly two hours, this feature-length documentary is ambitious and expansive, generous in its scope, as it covers many complexities and facets of the Bahujan identity. It is a necessary intervention at a time when Ambedkar’s name is invoked tokenistically for political appropriation. Important historical events are interwoven with present-day realities in a way that illuminates both the persistence of casteist narratives and the longstanding resistance. Jyoti Nisha delves into media data, citing that, as recently as 2006, 35 major Indian media houses had no Dalit or Adivasi journalists, and only four from OBC backgrounds. She highlights the structural exclusion that shapes representation in Indian media, a system designed to invisibilize Bahujan voices.

Still from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then – Dalit Asmita Yatra

Pa Ranjith, who is also the co-producer of the documentary, features in it, narrating how Bahujans are typically depicted in Indian cinema as dirty, poor, uneducated, lacking willpower, and incapable of self-respect. He adds that, as a filmmaker, he has deliberately and creatively broken those stereotypes by showing the Bahujan character to laugh, wear good clothes, enjoy, and engage intellectually. He provides references to the Tamil self-respect movement led by Pandit Iyothee and how it inspired the Dravidian movement.

Interviews with Dalit feminist thinkers like Cynthia Stephen and Urmila Pawar highlight how mainstream feminism often fails to address the caste-specific patriarchy faced by Dalit women. We hear Cynthia Stephen elaborate on how Indian feminism, dominated by savarna feminists, ignores the caste, gender and class intersectionality that affects Dalit women. She gives an example of the Devadasi system, which she defines as the religiously sanctified sexual slavery imposed specifically on Dalit women. She talks about how manual scavenging is exclusively done by the Dalit communities, and women within them live in the most precarious circumstances. Through these examples, the systemic sexual violence inflicted on Dalit women is laid bare. The documentary argues that the Indian society, deeply shaped by caste divisions, is fundamentally designed to be unequal for women, and any feminism that doesn’t grapple with caste is incomplete.

Dalit activist, Raya Sarkar, also known for creating the List of Sexual Harassers in Academia (#LoSHA) sheds light on the double standards of feminist politics in India, particularly how Dalit women often struggle to find allies within the mainstream feminist movement, even as Indian feminists show solidarity with the #MeToo movement globally.

The documentary draws attention to the digital space as yet another space of discrimination, hate and online violence. It references the 2018 closed-door conversation between Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and a group of women working in journalism, activism, and academia to discuss issues of online abuse and safety. Dalit rights activist and founder of Project Mukti, Sanghpali Aruna Lohitakshi attended this meeting and as a part of their ongoing campaign to raise awareness on caste and gender intersection in Indian patriarchy, she handed the poster of “Smash Brahmanical Patriarchy” created by Dalit activist and founder of Equality Labs, Thenmozhi Soundararajan. The picture of Jack Dorsey holding the poster was posted by a Twitter employee on Twitter, which led to online hate towards Jack Dorsey but more so, towards Sanghapali Aruna, who got casteist slurs and rape threats from upper caste Hindu online users and allegedly right-wing bots.

Thenmozhi Saundararajan, who appears in the documentary, says, “for a day Jack Dorsey experienced what it is like to be a Dalit woman.” This moment in the “Smash Patriarchy Campaign” eventually led to Twitter including caste in its hateful conduct policy. We hear Soundararajan highlight how important it is for Dalit-Bahujan “to keep telling their stories, build strong advocacy pipelines and to not back down in the face of the pressure of Hindu Nationalists.”

The documentary calls for digging deeper, sitting with discomfort, and truly committing to the annihilation of caste, a goal the filmmaker is not shy about declaring. Its structure flows like a thinking mind, going back and forth, connecting different events from various timelines to convey the common message they share.

The documentary juxtaposes the caste-based gender and sexual violence experienced by Dalit-Bahujan women with the Hindu Code bill that Dr. B. R. Ambedkar proposed in the parliament in the 1950s, which was vehemently opposed by Hindu parliamentarians, many of whom were women. The Hindu Code Bill was the most progressive bill that ensured property rights and other equal rights to women. We hear Dalit feminist Riya Singh referencing the works of feminist theorist Gerda Lerner, who has written about the origins of patriarchy. Lerner says that the roots of patriarchy in any society could be traced back to its oldest codified text. In this context, Riya Singh asks why the Indian feminists haven’t looked at the Manusmriti, the oldest Hindu scripture codifying caste and gender roles. She states that the Hindu Code Bill, created and proposed by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, guaranteed women equal rights, yet he never received the recognition he deserved for it. The documentary encapsulates the contributions of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar and the anti-caste movement that continues to carry his legacy forward, despite facing all the backlash, trials, and tribulations that it goes through.

Cynthia Stephen, activist, writer, and policy researcher, discusses how patriarchy shapes the lives of Dalit women in ways that are distinct from the experiences of privileged-class women.

Dalit feminist writer Urmila Pawar shares memories of her early experiences learning about the Ambedkarite movement alongside other women.

Thenmozhi Soundararajan, anti-caste activist and Executive Director of Equality Labs USA, recounts the Twitter storm after Jack Dorsey held the “Smash Brahmanical Patriarchy” poster.

US-based lawyer and activist Raya Sarkar discusses how upper-caste women’s conflicts of interest, due to male colleagues’ sexual harassment accusations, isolated Dalit-Bahujan women during the #MeToo movement.

At its heart, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then weaves a rich tapestry where diasporic Dalit voices, Ambedkarite scholarship, and crucial historical moments, such as the Mahad Satyagraha, the Poona Pact, and the Hindu Code Bill, along with the contributions of figures like Pandit Iyothee Thass, Jyotirao and Savitri Phule, are intricately interlaced to remember, repeat, and remind us of an Ambedkarite cultural resistance and a call to discover, understand, and commit.

At the onset of the documentary, Jyoti Nisha makes her political standpoint very clear. She prefers using the term “Bahujan,” which means “masses.” This radical political identity, envisioned by Kanshi Ram5, aimed to mobilise the formerly untouchable castes, constitutionally termed as Scheduled Castes, the Tribal and Indigenous communities, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backwards Castes. Together, they comprise approximately 85% of the country’s population. This political choice stems from the reflections and research the filmmaker undertook before embarking on this documentary.

The documentary calls for digging deeper, sitting with discomfort, and truly committing to the annihilation of caste, a goal the filmmaker is not shy about declaring. Its structure flows like a thinking mind, going back and forth, connecting different events from various timelines to convey the common message they share. It is a tall order to delve into all these complex events. The audience is offered a perspective on several important moments in anti-caste history, from then, led by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, and how the impact of his radical actions continues to shape the minds of anti-caste individuals now.

The narrative structure, which interweaves multiple complex stories without distinct chapters, may pose a challenge for novice audiences seeking a linear understanding. Yet, this format also signals a deliberate political choice. Does this unconventional approach, then, serve to immerse the viewer in a more authentic, perhaps less didactic, experience of the Bahujan perspective, one that demands active engagement rather than passive reception? To embark on a journey with a Bahujan mind and lens necessitates hard work from the audience in a society still enchained by caste, which is deeply unsettled by those who challenge its hierarchies.

Jai Bhim supporters celebrate Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary.

Birth anniversary of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar is celebrated at Deekshabhoomi in Nagpur, Maharashtra, with a live performance by Marathi singer Chandan Kamble, known for his devotional and folk songs about Dr. Ambedkar.

The visual and sound elements reflect Bahujan aesthetics. Vibrant hues of blue, echoing the Ambedkarite movement’s flag, fill the frame, while the OST – Jai Bhim by Shankuraj Konwar and background score by Rakshit Malhotra, Abhishek Bonthu & Hopun Saikia draws from the Bahujan cultural landscape, incorporating music by Arivu of The Casteless Collective. As one of Arivu and Chinmayi Sriprada’s songs plays, the screen shows young girls in blue scarves enthusiastically performing Maharashtrian folk music with the lezim. The lyrics proclaim, *“*Kanagi6 is not our role model, let us celebrate Madhavi7 … come, let us become Phoolan Devi8 …” These lines by lyricist, Uma Devi & Arivu highlight how Bahujan women are challenging patriarchal norms, rejecting imposed ideals of the “good” and “bad” woman, and embracing figures who symbolize autonomy and resistance.

In the end credits, Jyoti Nisha reflects on why she undertook the enormous and challenging task of making this documentary. Not wanting to engage in the tiring task of explaining caste over and over again, a burden often placed on caste-oppressed individuals, she envisioned this documentary as an educational tool and a cinematic offering and invitation that could reach across caste lines, shake assumptions, and expose the violence inherent in the savarna gaze.

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then, does not offer easy answers. Instead, it invites its viewers to witness, learn, and unlearn – to commit not just to speaking about annihilating caste, but to doing the work, persistently, painfully, lovingly. For those who are willing to accept this invitation, this homage serves as a guiding companion on this journey.