Claudia Pagès Rabal, Aljubs i Grups, 2024, Photo: Aron Skoog.

Alba Folgado is a curator based in Sweden. She received her MA in Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art, London. Currently, she works as curator at Köttinspektionen, Uppsala. In addition, she is founder and director of ‘A Movement to Hold’, a nomadic archive of artistic representations that focuses on re-visiting critical and non-hegemonic experiences.

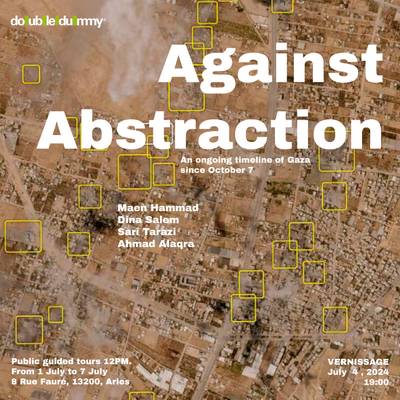

In spring 2025, Index – The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation in Stockholm informally announced that, together with Manifesta, they would produce a new body of work by artist Claudia Pagès Rabal, whose practice addresses themes such as the protean history of the Iberian Peninsula, global migration movements, territorial appropriation, and the cultural diversity and mix in the Mediterranean region. In recent years, Pagès’s work has been exhibited at several international venues and biennials, yet, despite its relevant themes and gaining significant attention, it hasn’t been presented in the Nordic countries with the same veracity, perhaps because, at least in the case of Sweden, looking towards the south of Europe or including narratives that are not North American, Nordic, or anglophone is still rare. The co-production between Index and Manifesta culminated in the presentation of Aljubs i Grups, a video installation revolving around questions of water flows, power structures, paper, and language production, at Index as a solo exhibition titled ALJUB. The work was first shown during Manifesta 15 Barcelona Metropolitana, the European Nomadic Biennial 2024. Although the exhibition was presented at Index for only five weeks, its content – foregrounding critical histories from Southern Europe – and the institutional choice to host it marked an important gesture towards expanding the cultural and political scope of art discourse in Sweden.

ALJUB opens with references to publishing or editorial work; it can be read as a book. The longest wall at Index serves as the spine of the book, guiding the viewer through the content in almost chronological order. Part of Index’s curatorial identity is to explore editorial work as an extensive artistic practice. They have an interest in the editorial as a performative attitude, evident in their programming through the selection of topics and artists, and, in this case, the exhibition’s architecture.

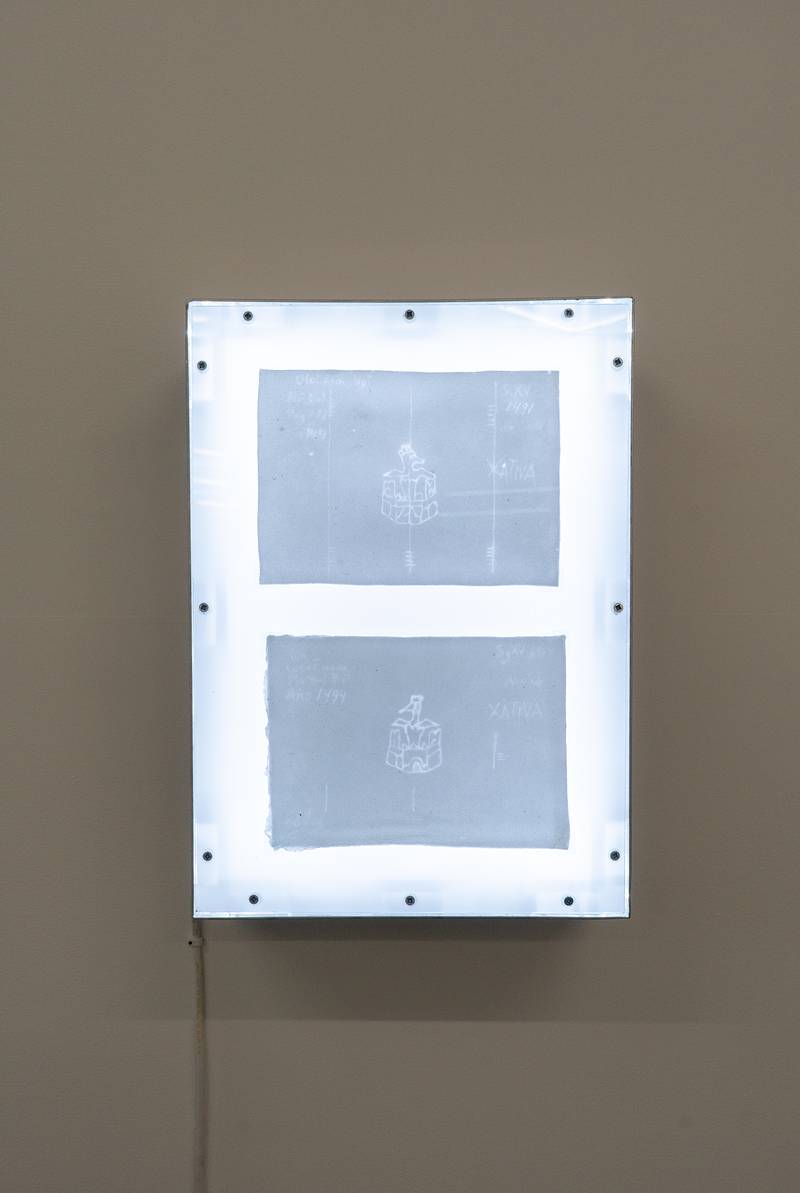

Watermarks displayed at ALJUB, 2025, Index. Photo: Aron Skoog.

The exhibition begins with two watermarks displayed on a lightbox, referencing the artist’s research on Xàtiva, Valencia. Lending itself to the exhibition’s title, ‘Aljub’ is an Arabic word meaning cistern or tank, referring to a structure built to collect and store rainwater. It is presented as a reference in Pagès’s video and as a concept she explores throughout the exhibition, both in its form and in its role in the history of Arab rule in Spain (711 to 1492). From the watermarks, the exhibition moves into a table-tank showing Pagès’s drawings and diary notes from the process, along with the film’s script in sound form. The following “page” presents a series of paintings on handmade paper depicting various water flows and watermarks, as well as utopias and discourses that unfold in the video, which is installed in the final room (or chapter) of the exhibition.

Pagès highlights the inseparable relationship between paper and water – the medium through which the material takes shape and gains its texture and strength. We recognise how “paper” validates institutional discourse and state power, such as written communication in so-called official papers.

Throughout the years, Pagès has investigated language – how we communicate, which words are used in different contexts, what jurisdictional language is, and the habits and relationships that surround it – through performance, video, and installation. In one of her previous projects, Gerundi Circular, she explores ‘gerund’, a non-gendered, non-numbered, neutral verb form that is repeatedly used and abused by power structures to punish individuals and treat them as objects or actants. For ALJUB, she turns her attention to ‘paper’ as another version of language – paper as the carrier of “the word”, paper as the representation of history, power, bureaucracy and oppression. Pagès interrogates the physical nature of paper by tracing its material origins and production process, which is deeply intertwined with water. To make paper, wood is first chipped and cooked to break down its fibers into pulp. This pulp is then suspended and floated in large vats of water, allowing the fibers to disperse evenly before being drained, pressed, and dried into sheets. Through this process, Pagès highlights the inseparable relationship between paper and water – the medium through which the material takes shape and gains its texture and strength. We recognise how “paper” validates institutional discourse and state power, such as written communication in so-called official papers. Pagès also examines how paper’s physicality has enabled the reinforcement of authority through watermarks – small designs embedded in paper that originated in Bologna in 1282 and have since been characteristic of occidental paper. Formed by a metal thread, watermarks are visible only when the paper is held against a strong light source and are used to prevent forgery and to express uniqueness and veracity.

The exhibition at Index includes research materials and other works that expand on it. Because of this, the work feels adequately contextualised, despite the vastness of the documentation and the intricate layering of elements such as performance, dance, spoken word, graffiti, and historical references. Index’s co-directors, Marti Manen and Isabella Tjäder, tell me about their collaboration with Pagès and the difference between her commission for Manifesta and what is presented here. Their dialogue with her began long ago through video calls and visits, intending to follow and support her creative process while introducing her to Index’s work ethos – one that, despite material constraints, prioritises long-term relationships and public-centred mediation in every exhibition. They prefer presenting process-based material, such as preparatory drawings, that contextualise the research, rather than rely solely on the spectacularity of a final piece.

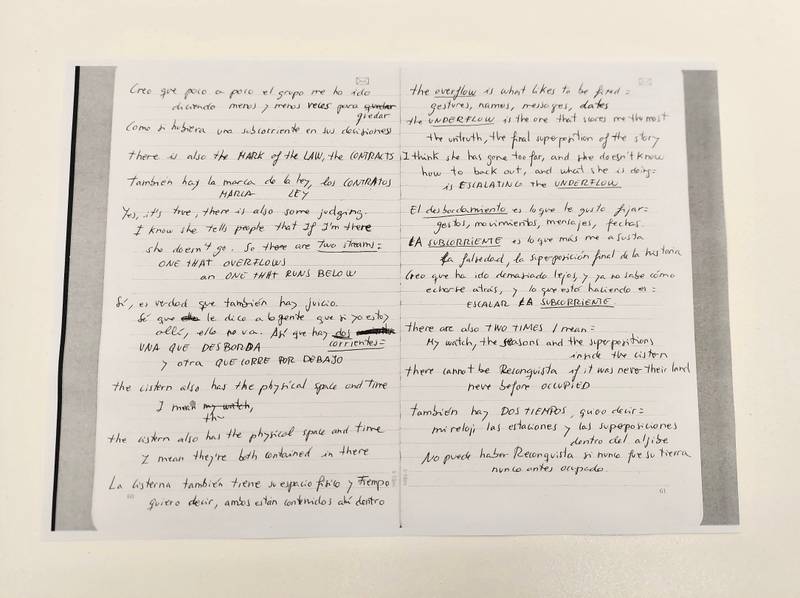

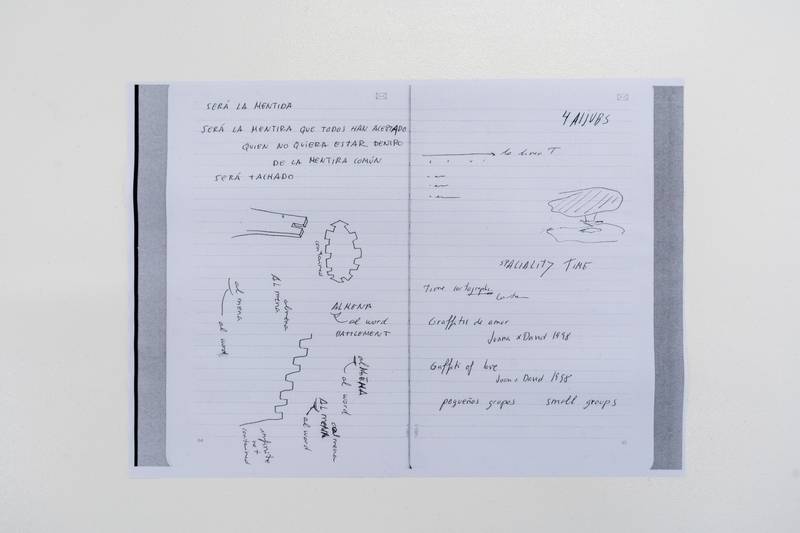

From Claudia Pagès’ notebook, notes and copies displayed at Index, 2025. Photo: Alba Folgado.

The centrefold of the exhibition is a video that delves into the discoveries the artist made at a water cistern (or aljub) in Xàtiva, Valencia. This cistern, built during the Caliphate (1244-1304) to supply water to an Islamic palace and repurposed over time – including its integration into a Christian convent in the XVI century and a hotel in the XX century – can represent a point of cultural divergence. In the video, we encounter the aljub as a place shaped by various physical forces (evoked through dance), verbal expressions (discourse and spoken word), and written contracts (such as graffiti from different historical periods covering its walls), revealing how power operates across various eras and systems. In the video, we see a group of friends in which power is inflicted by gossip that keeps one person away; or, inside the tank, power is expressed through the writing of names on the walls, asserting presence and possession of the space. Through these scenes, the work suggests how power manifests at different levels and through multiple structures: through written language and symbolic elements that legitimise authority, and through spoken language as a means to influence and enforce dynamics of exclusion and social control within both intimate and larger groups.

Pagès leads us to a broader discussion in which institutional mechanisms are revealed and questioned. She foregrounds how language, water and paper have functioned as tools for legitimising exclusion and validating partial truths, like with the spoken word part of the video, a dialogue between two friends, a partial view on a conflict that is narrated as truth, but which can also be a biased story convincingly told.

If one were to encounter the video on its own, apart from the other elements of the exhibition, one might conclude that nothing further is required to understand the message the artist is trying to convey. Through its choreographic elements, symbols, sound, shifts in setting, turns of the camera, spoken word, the use of several languages, and what appear to be handwritten subtitles, the work is precisely composed and scripted, with navigation that feels intuitive. It is formally complex and direct in its message, visible in the video’s narrative, where the aforementioned elements appear together brought to us through situations that we can intuitively understand: a group of people gather around the cistern; they dive into the water and comment on what they find inscribed on the walls: names, dates, drawings of penises, and marks indicating domination or possession of the space regardless of the period in which they were made. Later on, the same group dances among the ruins of the former palace. Two members discuss their feelings about another person within the group, and suddenly, the institutional and individual uses of language that once felt distant become recognisable. They are the same gestures of power, the exact linguistic mechanisms used to collectively accept a lie, a contract enacted against another person.

This way of showing how domination operates, whether in small groups or large structures, is clever and compelling. By grounding the work in a familiar situation – such as a group of friends with its manipulative lies and social dynamics – Pagès leads us to a broader discussion in which institutional mechanisms are revealed and questioned. She foregrounds how language, water and paper have functioned as tools for legitimising exclusion and validating partial truths, like with the spoken word part of the video, a dialogue between two friends, a partial view on a conflict that is narrated as truth, but which can also be a biased story convincingly told. Even though she explores these connections through video, they could just as well be understood as a carefully choreographed performance or theatre work.

The video communicates with clarity, permeating the viewer’s understanding with ease. The works in the exhibition that serve as documentation expand the project and encourage reflection. This becomes particularly evident with the two watermarks that Pagès encountered and reproduced during her research in Xàtiva. Here, she found a symbol resembling a hen emerging from a castle. In the first watermark, dated 1491 (before Columbus), the hen faces right – one might say towards Europe. In the second, dated 1494 (after Columbus), it turns to the left, which could be interpreted as towards America. This curious watermark and the possible historical shifts contained in its two versions seem to encapsulate the essence of the exhibition: a concise yet grand gesture – as with the assumably difficult installation of the huge curved screen for the video and all of its connections – in which layers of meaning (documentation) unfold for those curious enough to explore it further.

Collection of exhibition texts and posters at Index, 2025. Photo: Alba Folgado.

Claudia Pagès Rabal, Research material, 2025. Photo: Aron Skoog.

The table-tank placed at the centre of the exhibition space contains documentation such as preparatory drawings for the construction of the large curved screen on which the video is projected, as well as texts, scripts, and audio clips – recordings of Pagès playing the guitar, which she later uses as a score for the video’s dialogues and music. These elements allow the viewer to delve deeper into the artistic process, connect with the fragments and thoughts behind this operatic/performative composition, which eventually unfolds into a complete work in the video. By presenting this material in the exhibition, the artist, along with Index, embraces experimentation and hybridity in the display methodology, making the process of the work visible to the public.

Leading up to the video is a series of drawings on a transparent wall that separates the space and invites us to look at it from both sides. On the more illuminated side, we see utopian and dystopian depictions of water and soil flows, stone walls, and a mountain with two faces – the visible superstructure and the less visible infrastructure. All of these appear on handmade papers embedded with colourless filigrees, connecting to the physicality of the caves in Xàtiva and possibly similar spaces, where structures separate as sharply as social codes do. On the other side of the wall, a dim light reveals the watermarks on the paper. These are long, reversed texts, almost impossible to read, evoking the idea of inaccessibility – the text, the word, and the paper as tools not only of communication but also of division.

Presenting at Index is a collective endeavour rather than a one-person project. Here, complex and layered artistic practices are made accessible to a general audience, a methodology derived and evolved over years of research and practice into the intricacies of relationships, social contracts, and self-perception within the team and participating artists.

In the processual parts of the exhibition, the Index team’s attentive commentary and guidance are pertinent, helping audience members understand the nuances of Pagès’s work. For instance, showing a guitar recording is important – the first step in the creation process that leads to the final musical composition of the video. Viewers don’t need extensive prior knowledge of the subject to engage with Pagès’s video work, as it addresses themes commonly encountered in our daily lives: bureaucracy, power dynamics, discrimination, appropriation, language, and structures. Although familiarity with the history of the Iberian Peninsula, Al-Andalus, and how Arab, Christian, and capitalist forces have intertwined over the centuries to shape the region might deepen understanding of the work, such background is not essential. At least when viewing the work at Index, its team is available to guide visitors – their commitment to mediation and dialogue has organically grown as part of their working method, evident not only in their approach but also in the placement of the office within the exhibition space. At Index, their office or working area is always located within the exhibition space. This means that each exhibition has to incorporate an area for the team’s workspace – an arrangement known to regular visitors. This unusual and intentional condition reduces the sense of intimidation often associated with art institutions. Here, visitors are offered introductions to the ongoing exhibitions or, at least, made aware that the team is available during their visit. It is a simple and effective mediation strategy.

It is also through exhibitions like ALJUB, focused on raising ideas and addressing political and social issues beyond dominant discourses, that one can see what Index is striving to achieve. As Tjäder and Manen put it, they work only with public funding, not private sponsors, which, so far, has allowed them to host the first solo exhibitions of many critical artists, whom they hope to help gain greater attention and secure exhibitions in larger institutions in Sweden. Reflecting on Index’s wider philosophy, Martí Manen explains, “Index has a clear DNA with several goals. We work with and for the artists, we offer international connections in terms of content and structures, and we understand contemporary art as a platform to think together about our society in complex ways. Politics, language, sociology, identity and performativity are approached through the lens of art. In fact, we see art (and the art institution) as among the last times/places opened to dialogical constructions of the world. We see our institution as a “warm institution”, something that wants to talk with you, discuss with you and help you as much as we can.”

By calling attention to various acts of writing and erasure, Pagès situates her work within a lineup of artistic practices that challenge inherited frameworks of seeing and acquiring knowledge and extends its resonance to questions of memory and resistance in contemporary art.

Index regularly presents artists and projects with a stronger engagement with social and political issues than other institutions in the city, its programming extending beyond exhibitions to include film screenings, book presentations, and student collaborations. Irrespective of how they are received, such programming offers alternative ways to engage with the exhibition, bringing value to critical thought and discussion about commodification. For this reason, one can expect to encounter at Index thought-provoking and genuinely reflective art. This does not mean that Index is entirely outside the established art circuit – their collaborations with institutions such as Moderna Museet in Stockholm, as well as biennials and exhibitions abroad, clearly show otherwise – but their experimental character allows them to maintain an analytical programme. Index works in a horizontal, experimental manner and transmits this vision to everyone they collaborate with, from the public to the artists. They facilitate an accessible, curious, and comfortable experience of contemporary art. The artists reciprocate by accepting the challenges of negotiating access to available equipment, resources, and other specialised needs, and still choose to embed their work in the space rather than take it over. Presenting at Index is a collective endeavour rather than a one-person project. Here, complex and layered artistic practices are made accessible to a general audience, a methodology derived and evolved over years of research and practice into the intricacies of relationships, social contracts, and self-perception within the team and participating artists. I connected with the work not only as a visual experience but also as the monumental proposition that it means: a work that exposes how lies are inscribed into History. This connection might have been difficult, or would not have formed in the same way, without the possibility of engaging directly with the documentation, experiencing the desacralisation of the object, listening to scores and touching papers, and receiving the quiet sense of contemplation offered in the exhibition.

In the context of Index, Pagès’s work appeared to me as an unlearning of history written through lies, appropriation, power, and distortion, one that defines my identity and, at the same time, feels distant.

The graffiti within the cistern and the more contemporary ones outside the water tank weave together subcultures across time. The shifting uses of the building that Pagès recorded in Xàtiva, its inscribed symbols, and even the production of paper confront many accepted falsehoods we encounter (and accept) daily. ALJUB is a thoughtful and enjoyable provocation, bringing together sensorial pleasure and a space for the expansion of critical thought. In doing so, it also projects onto broader conversations about the politics of language, its evolution and uses, and how colonial power shapes it in its own favour – how narratives are structured to legitimise specific histories while erasing others. By calling attention to various acts of writing and erasure, Pagès situates her work within a lineup of artistic practices that challenge inherited frameworks of seeing and acquiring knowledge and extends its resonance to questions of memory and resistance in contemporary art.