Egle Oddo, Performative Habitats

Raine Aiava is a Ph.D candidate in the Doctoral Programme in Political, Societal and Regional Changes within the Department of Geosciences and Geography at the University of Helsinki. Working in the field of human geography, he is part of the cross-disciplinary research group, Geographies and Affective Politics of Education, where his research explores the politics of difference in eventual encounters and emphasizes non-representational and more-than-human perspectives.

Mänttä Art Festival 2021 review

June 13 – August 31

Once upon a time – a previous life, really – I spent a good deal of time in Japan. I lived in a small village nestled in the mountains and traveled throughout the Kansai region, visiting temples, gardens, and cemeteries, studying Japanese Buddhism and its history. I found adjusting to life in Japan to be surprisingly easy. Whether this was because I grew up on an island in the pacific where Japanese culture had long constituted a significant thread in the tapestry of everyday life, or simply because I was content to be lonely, it’s hard to say. Still, I spoke very little Japanese and read even less, which, coupled with my distinctly American veneer, succeeded in keeping me adrift among the endless sea of signs that, paying little heed to my inability to decipher them, continued signifying all the same. Despite my solitude within this vast semiotic landscape, where communication was stripped down to predominately functional gestures – read: a lot of head nods, and apologetic bows – I was grateful for the excommunication. The exile felt appropriate to my contemplations on Buddhist teachings, and I felt sure that my loneliness would attend a somber attunement to the world.

Though I were to visit, during this moody winter pilgrimage, a great many famous and less famous shrines, temples, and gardens, there would, in the end, be precisely two moments that arrested my attention in what one might approximate as a transcendent experience – that acute esthetic surrender so akin to what religionists term ecstatic communion1. The first occasioning of this enchanting encounter was during a pilgrimage to Mt. Koya in the dead of winter, where, surrounded by Okunoin Cemetery and ensconced in a deep blanket of snow, I was arrested by a world suddenly expanded. Oversaturated, it enveloped and moved through me. As if I were seeing everything for the first time, and with profound clarity. Intimate but boundless; immutable but transient. Aching with significance yet divested of meaning. It was an experience that would come to dominate my research2. And yet it was the second event that would prove somehow more surprising, in both its source and its effect.

My return to Kyoto marked a shift also in my isolation: from a somber, silent world to a dense tableau of undulating fonts which for all its shouting nevertheless remained reticent for me, never quite coalescing into meaningful signification – from a quiet place among things to one apart. On this occasion, with the probable aim of continuing my cultural education, I decided to visit the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto – a large, functional, concrete and glass monstrosity (as these institutions so often are), where the entrance was only discernible by virtue of an out-of-place awning. Despite the unimaginative façade, what would confront me beyond the large glass doors remains somewhat difficult to describe. Not because there was anything unusual to encounter there – indeed, the vast and empty lobby which loomed white and bare above me and the mount of stairs that promised ascension into aesthetic enlightenment proved every bit conventional and mundane – no, rather what is difficult to get at is just how overwhelming the sense of familiarity was: it was nothing short of a homecoming. I had to sit down. Had to catch my breath, which seemed suddenly to come easier. I had been adrift – I had recognized that much – but it was only here that I was able to recognize it. Only here, in the church that Art built, with its lexicon so familiar and its doctrines so concrete, did I finally feel grounded enough to recognize how unsettled I had been, and how much I missed home. Not America. Not specifically. But home nonetheless: a centeredness, an orientation. Here, in the vast gallery spaces, where each painting was centered at 146 centimeters and surrounded by vacated stretches of white wall. Here, where history was spatially demarcated: from abstract expressionism, to action painting and Gutai performances, to happenings. Where a whole cosmos was aesthetically unfolded and affectually insistent.

It was a sensation that returned to me again this summer, when I found myself approaching the Mänttä Fine Arts exhibition space, Pekilo: A feeling of warmth, comfort, familiarity. A feeling of homecoming. I mark that this too came on the heels of enduring isolation. (Though we’re calling it “self-isolation,” and hoping that emphasizing the volunteerism of the word will help. It does. A little.) And, I should say, that I don’t think it a coincidence that a degree of loneliness should prefigure the sudden rise in me of a yearning to connect and to be connected to, nor the sense of comfort I should find in the promise of familiar channels which would deliver me from that solitude. Indeed, it’s been a long year. And I haven’t left the house. Haven’t been with people or met friends. No Christmas. No birthdays. Just faces on screens, as if we’ve all become news-anchors, correspondents abroad. But now the sun is out, and I’m outside, and Mänttä is a lovely little Finnish village. And weirdly enough, standing there, at the entrance of the venue, it felt like being back in New York City, pushing into Chelsea. Or maybe, less outrageously, like visiting the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio. I felt a connection to something extra-ordinary, something metaphysical, that spanned continents and countries. A shared world. A language I understood, a hymn I knew. I had already felt the stirrings of recognition from the road, where I could see glimpses of bright paint climbing the factory walls and black plastic shapes terraforming its roof – an unmistakable vocabulary. I paused for a moment, taking in the warm day. I wanted to extend the sensation that was growing in me, of a world expanding yet intimately linked.

Bees and insects that I couldn’t name danced about the verdant oasis, as captivated by its perfume as I was. Thoughts of art, and rubrics, and tactics flew. Involuntary memories flooded me, and I dreamed of wind off the Pacific, and a childhood on the mountainside. I stood motionless a long while, overwhelmed by the phenomenality of the encounter – by a sense of the pure givenness of things, outside intentionality – where the scaffolds of intelligibility momentarily fell away and being seemed to outstrip being-towards.

But perhaps my hesitation was something else. A trepidation. A desire to hold tightly to the eagerness that had flooded me just moments before but which now took flight in the face of well-worn syntax and the too-familiar discursive signatures. For even at the entrance, peeking into the cool interior, there was little doubt of what I would find inside. When it comes to contemporary art, the list is pervasive: Paintings and sculptures, extended video works, records of performances, digital interactive works, site-specific installations, documentary photography, appropriated objects, perhaps an intervention or two. Obviously, an inventory of mediums is hardly meaningful on its own. We should probably endeavor to brace it up with a nod to the many critical perspectives that will no doubt be invoked: feminist, Marxist, post-humanist as well as humanist, environmentalism, post-capitalism, relationality, vital materialism, individualism and collectivism, and so on. Maybe more specific still, we can follow Jacques Rancière’s perceptive outline of critical art to anticipate the tactics that would be employed: the playful, which aims through appropriation, high-jacking, or deflection to sharpen our attention to the interplay of signs, procedures, and framings of everyday life, often through shock and juxtaposition; the inventorying of heterogeneous elements in an arrangement of materials which operates on them in such a way as to represent them as manifestly present, demanding a witness; the encounter, whereby relationality is invoked through an appropriation and transfiguration of the exhibition space in order to invite the viewer not just to parse signs and witness presencings, but to register the relational bond between the artist, the environment, one another, and world; and mystery, which like the relationality of the encounter, calls on heterogeneous elements to illuminate the fabric of a world held in common.3

Strictly speaking, the fact that the means of contemporary art may be conceptualized and prefigured in no way implies that the affectual geometries of these works can be. This was something I was immediately reminded of as, having decided that I needed to recalibrate myself before entering the main exhibition hall, I headed out behind the pavilion instead, where I spied a plot of wild terrain cornered by a purposeful fence (and thus bearing all the earmarks of a contemporary artwork). I had moved only a few paces towards this garden before being arrested by a shift in the breeze which carried upon it a sharp but delicate scent: the smell of Wildflowers, late to bloom? Or perhaps the freshly dampened earth had mingled with bruised leaves or fresh cut grass? Surprisingly, arriving at Egle Oddo’s Performative Habitats precluded any discernible answers, as the fenced-in garden was chaotic and overfilled – though clearly intentionally cultivated – with innumerable types of flora and fauna, swaying merrily in the wind. Bees and insects that I couldn’t name danced about the verdant oasis, as captivated by its perfume as I was. Thoughts of art, and rubrics, and tactics flew. Involuntary memories flooded me, and I dreamed of wind off the Pacific, and a childhood on the mountainside. I stood motionless a long while, overwhelmed by the phenomenality of the encounter – by a sense of the pure givenness of things, outside intentionality – where the scaffolds of intelligibility momentarily fell away and being seemed to outstrip being-towards. I found my attention drifting to a strange little bug working its way through the maze of vegetation and thought again of the title of the work, of the endless relation of embodied practices, co-emergent with and informing of the habitat they simultaneously perform. As the material summons of the garden fell away and I returned to the conceptual playground of art, the performative moved to a different register, from praxis to citation, from performance to performativity: from the more-than-human negotiations which brought the space into being to the way that art itself intervenes upon and transforms a space and seems to exercise its own agency and effect. And I could not help but wonder whether it isn’t to this register that we’d have to transcend were we to search out the “error” that the festival made its theme. It was a trip I wasn’t keen to take. From eventual encounter to reifying contemplation. From Koyasan to Kyoto.

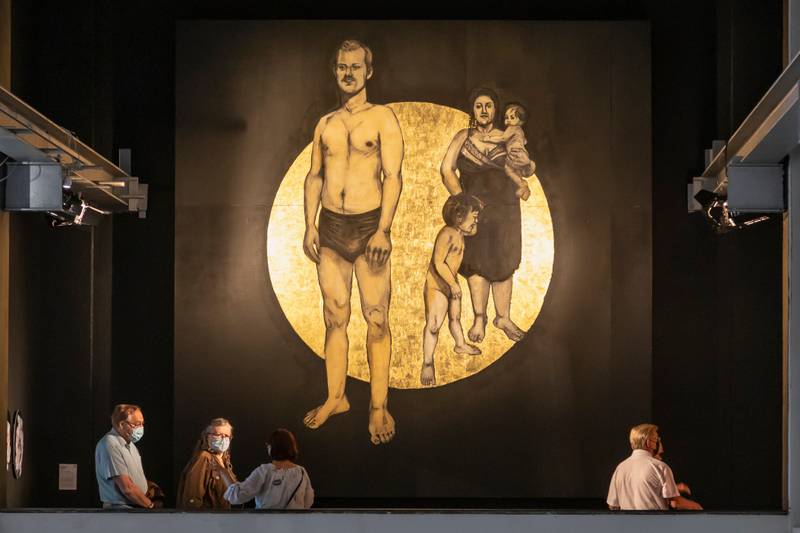

Timo Koko, greenhouse installation of Momentary Appearance: Forest

In contrast to the open space given to those handful of artworks fortunate enough to be dispersed across the exterior grounds, where, for instance, the slow death of Timo Kokko’s transient biome or Suva’s ligneous meditations on human identity were allowed some measure of autonomous affect, the Pekilo building was crammed with nothing short of 41 discrete works of art – an enormous undertaking, for both exhibition coordinators and viewers alike. And, while it must be acknowledged that the layout of the exhibition and its general choreography did manage to insure that it was possible to face any given work more or less on its own – and rather importantly, that no work really seemed favored or highlighted in an especially coveted place of exposure but rather large works were arranged to consider the approach and intimate works were contentedly gathered in hallways or constructed rooms – while this care to the exhibition map must be acknowledged, it is also true that there was simply no getting away from a topography of loosely linked, but distinctly excursive, investigations. For despite the best efforts to segregate works appropriately – walls raised, rooms painted – the fact remained that though I found myself standing before an emotional family portrait – where a woman and her two children, haloed in brilliant gold, were tucked an alarming distance behind their stoic looking Finnish husband/father – I had arrived there by way of a wall of meme paintings. Not that Tiitus Petäjäniemi’s paintings didn’t themselves possess a charm and humor in both their presentation and content. But their irreverence and whimsy butted against Mariam Haji’s moody ruminations on love, life, and home, which fought for consideration just next door. In the same way, Ali Akbar Mehta’s powerfully confrontational book archiving the history of war found itself sandwiched between Ari Pelkonen’s very traditional abstraction of pine trees to the one side, and a constellation of small process-based abstractions to the other.

Each work was, by its very inclusion, mobilized on the grounds of this flattened rubric. And it was this collective function that, more than anything, overwhelmed my most sincere efforts to engage these individual pieces in the light of their genuine complexity. What was effected then, to absolutely no one’s surprise, was a kind of cabinet of curiosities, where artworks that might otherwise enunciate, challenge, or disrupt were instead gathered together to be presented as evidence of culture.

Mariam Haji, Taking a Chance on Love

This organizational structure produced in me a kind of schizophrenic disposition, where active perception was foreclosed upon by the restless operation of mere recognition. My attention jumped, consumed, and digested quickly only to run ahead again. For if perception involves a surrender, an undergoing which is thoroughly receptive, recognition is satisfied with attribution and signification, eager to fall back on previously formed schemes and criticalities4. Thus, despite the generosity with which these artworks were furnished, I passed by, merely marking tropes: of interventions, of surrealist provocations, of activism and politics with a capital P, along with petitions for a politics of everyday life; I marked the syntax of the artists, yet I struggled to discern their voice. And I began to wonder, while passing from a too-sleek facsimile of a restaurant by way of a canopy of trees built from scaffolding and tarp, whether art itself wasn’t in the way. For if in the mountains of Japan I had realized something of an aesthetic surrender, it was because I had been overtaken by the sensuous reverberations that rose within me, without my “being able to be anything other than the place of its manifestation and the echo of its power.”5 Deracinated and derealized, I had been lost “– literally, ‘alien-ated’ – in the aesthetic object”6 which constituted itself through me. I was given, as a pure receptive subject – my factical history momentarily severed and my capacity to intend the phenomenon that moved through me suspended.7 But here, I found no such sublimation. Though I might recognize all the signs of communication, actual communion seemed impossible, interrupted by readily digestible avenues of interpretation – like living with a loved one so long that you know what they will say without needing to ask, and by thus prefiguring them foreclose any possibility of difference stemming from or arising within them. The sense of familiarity that had warmed and excited me on my approach had in no way disappeared. Rather, it was precisely because it continued its work that the artworks themselves remained estranged. Which is to say, I was not moved by the art in the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, I was comforted by Art. And I am not entirely convinced that the two are compatible.

What then to make of this impasse? Is it a deficiency within me? My cynicism? Ego and arrogance? Certainly. By all accounts I possess these defects in spades. But just as assuredly, it was also a direct result of the institutional framework that guided this exhibition. Because the XXV Mänttä Art Festival was, above all, a survey show. Its function was performative. Its aim was not only to highlight contemporary art as such, but to mobilize a three-fold operation which: 1) staked a claim on what contemporary art in Finland is (inclusive, diverse, sophisticated, progressive); 2) announced Finland as contemporaneous (and in-line) with a broader, international “artworld”; and 3) institutionalized these enunciations for the general public in order to create a normative self-portrait of a Finnish contemporary art “scene” (via a theory of performativity in which saying is itself a kind of doing) which operates on as well as reflects broader societal values. These directives were visible not only in the explicit communications of the festival – its website noted that almost half of this year’s artists came from multicultural backgrounds8 – but also in the organizing principles, curation, and lack of substantial contradictory discourses present within the show itself. Each work was, by its very inclusion, mobilized on the grounds of this flattened rubric. And it was this collective function that, more than anything, overwhelmed my most sincere efforts to engage these individual pieces in the light of their genuine complexity. What was effected then, to absolutely no one’s surprise, was a kind of cabinet of curiosities, where artworks that might otherwise enunciate, challenge, or disrupt were instead gathered together to be presented as evidence of culture.

Small wonder, then, that the theme of this exhibition – “To err is human” – should feel so hollow: its function was redundant. Rather than augmenting interpretive routes, it formed an all too familiar epoxy with which disparate works were to be bound, or indeed conceptually backloaded. Of course, the theme itself wasn’t necessarily the problem. It’s certainly sufficiently open, and available to a myriad of critical approaches – though it did strike me as rather passé (The centering of humanity displayed a disregard of posthuman and non-representational critiques of humanism, subjecthood, and the Anthropocene that seemed altogether too sincere to overlook). No, it’s simply that a thematic as such was superfluous. Remove it, and the exhibition functioned just the same. The survey itself performs.

Despite the homogenizing affect inherent in the subjugating strategies of such institutional surveys, there was a lot to admire here. There was a generosity that ran through the exhibition, from the earnest vulnerability and sincerity of the artists to the careful exhibition design to the sheer magnitude of curating 67 artists in a single space over the span of two years and through a pandemic.

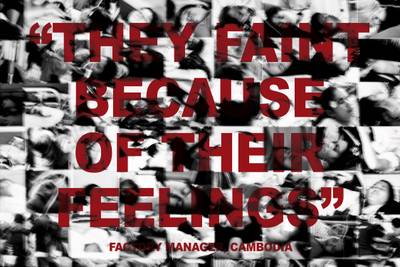

Rosamaría Bolom, Edwina Goldstone, Sepideh Raaha, Arlene Tucker — Mechanics of Conformity

It is critical to highlight that important discourses were lost to this flattening effect. Impoverished by the shows’ weighty imperatives and plethora of voices, the works instead competed for engagement. Issues of immigrant experiences, for instance, were inevitably relegated to the same level of importance as art-as-technical play or art for arts sake. In the best situations, installations managed to separate themselves from the exhibition enough to carve out their own worlds – though this proved a rare possibility in the packed space. Mirror, by Mechanics of Conformity-MOC, for instance, was able to successfully curate an intimate space through a four-channel installation that situated the viewer right in the middle of an open dialog between four women of color. This enabled the significance of their discourses – on norms and representation, vulnerabilities, and their inmate relationship to culturally specific embodied materialities such as hair – as well as their methodology, to momentarily overtake the stratifying thematic by physically surrounding and implicating the spectator. Contrast the affectual potential of this presentation with what should have been an equally powerful video by Anna Knappe & Amir Jan, and we observe how, despite its forceful subject-matter – on the impact of violent images – and compelling composition, Girl in Green found itself a casualty of the hegemonic aspirations of the show.

Despite the homogenizing affect inherent in the subjugating strategies of such institutional surveys, there was a lot to admire here. There was a generosity that ran through the exhibition, from the earnest vulnerability and sincerity of the artists to the careful exhibition design to the sheer magnitude of curating 67 artists in a single space over the span of two years and through a pandemic. This generosity was nowhere more evident than in the monumental commitment to a sustained engagement with the artists through both traditional and new media platforms, including: a sleek exhibition catalogue which brought much needed discourse to the stage, or provided a proximal space for artistic interventions, as each artists saw fit; a genial video series that invited contributors to consider the question “Why do I make art?”; and a series of “Presentations in 14 Languages’’ which solicited artists’ reflections on the work of their peers as well as further cemented this exhibition’s commitment to diversity and inclusive representation. In this way, there was ambition here too. A drive to perform the very community one wants to realize. To infiltrate existing systems, as the exhibition curator Anna Ruth puts it, and bring about change silently9 – through reiterative and citational practices.10

That is, through recognition.

And suddenly, I began to wonder whether I hadn’t had it backwards: whether art wasn’t in the way of Art.

Still. If Art is to accomplish this, it’s important to turn attention away from essentializations, of which the roll call of subjectivities as an ever-present critical condition remains a nuanced part,11 and “towards more open processes of subject construction, counter-subjection, refusals and disidentification”.12 Otherwise we risk hypostasizing social difference under the familiar intersections of race, class, gender, sexuality, citizen, ability, and age – treating subjectivity as derivatives of these categories.13 Are the artworks in this exhibition capable of carrying forward the nuanced investigations and provocations necessary? Or are their affectual potentialities foreclosed upon and instrumentalized through hegemonic means? What I mean here, and what accompanied me off the exhibition grounds and back to my dreary isolation, was an all too familiar despondency: If we are to procure an art that works for us, I wonder whether we ought to be courting anything proximate to a so-called artworld.