Uwa Iduozee, 2020

Ndéla Faye is a journalist and writer. When she’s not wallowing in an existential crisis and getting wound up by capitalism and daily microaggressions, she spends her spare time knitting scarves, cocooning with her family, reading fluffy and spicy romance novels, and leaning into her ‘wellness era’.

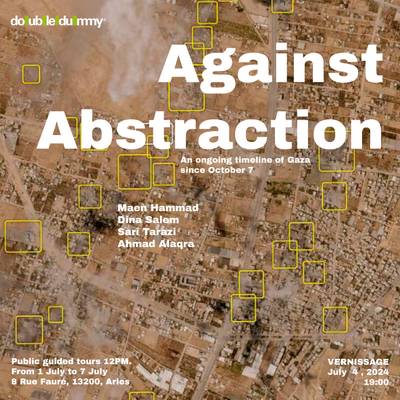

Blind Spot(s) is an exhibition at The Finnish Museum of Photography, by Uwa Iduozee (b. 1987), a Finnish-Nigerian documentary filmmaker, cinematographer and photographer, based in New York and Helsinki. In his words, he strives to tell stories that are often neglected by the mainstream media. Blind Spot(s) features photographs taken by Iduozee in the United States in 2020.

I enter the bare room with white-painted walls, lined with colourful pictures of Americans during 2020; a year that will forever be etched in our minds as the Year of the Pandemic, a year of lockdowns, Black Lives Matter protests, turmoil, heartache and heartbreak, uncertainty and anxiety.

From the moment one steps into a gallery, the “vibe” is a critical aspect of the experience. I try to get a ‘feel’ of the space and attempt to gauge the space itself; the people, the lighting and the atmosphere, and the placement of each photograph. There are images of wire fences, a sandy beach at Coney Island, a red Mustang, fire escapes and steam pouring from New York City streets. There are pictures of white and black Americans living ordinary lives amidst a pandemic that swept through the world, the US presidential elections of 2020 and an anti-racist movement that sent ripples around the Western world.

Iduozee took the photographs as part of work assignments for various media outlets, and the pictures have been taken all over the United States. The photographs are almost like a game of ‘Spot the most American stereotypes’-bingo. How can a place feel so familiar when I’ve never even visited the United States? Is America really so stereotypical?

One of the pictures immediately calls out to me. A photograph of two young boys looking into the camera with serious, pensive looks on their faces. Who are they? What is their story? I look over to find some information about the picture; a title card or a note to give me an indication of what stories they might have to tell, but there is no additional information about them.

I leave the exhibition still wondering about the people in the portraits, and decide to go straight to the source and ask Iduozee if there is information that I missed. He answers the phone call on a sunny August morning at his home in New York City.

“Not including any information alongside the pictures was a conscious decision. All the pictures in the exhibition were photographed in a photojournalistic context, where the people and their stories have had very specific frames to fill,” Iduozee explains.

“I decided that I would contextualise everything, or not contextualise anything at all. In the end, I decided to let the picture tell the story. It’s also impossible to summarise a human into just a few lines. What information would I have included about each picture? What information would I have left out? How would that have influenced the audiences looking at the photographs? Each picture is a reflection of what kind of world of values you have and what kind of life experience you have and what kind of society you have lived in,” he adds.

Uwa Iduozee, 2020

Challenging the neutrality of images

An integral part of the exhibition is an interview with Iduozee, conducted by Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger, Chief Curator at The Finnish Museum of Photography. The written text complements the exhibition and discusses how only the privileged can afford to remain apolitical without it affecting their everyday life. Iduozee believes that remaining apolitical is a political act in itself and that only those who have a privileged viewpoint could interpret photographs as being neutral.

“The idea was that the exhibition’s visitors would first read the interview and then look at the images. It was a gentle nudge; a poke, to make people question their own position while they were viewing the images,” Iduozee says.

“I decided that I would contextualise everything, or not contextualise anything at all. In the end, I decided to let the picture tell the story. It’s also impossible to summarise a human into just a few lines. What information would I have included about each picture? What information would I have left out? How would that have influenced the audiences looking at the photographs? Each picture is a reflection of what kind of world of values you have and what kind of life experience you have and what kind of society you have lived in.”

He explains that his goal was also to challenge the fact that images are ambiguous or neutral. “They never are. Images will always be interpreted depending on who is looking at them,” he explains. He wanted to use Blind Spot(s) as a starting point for a conversation that would hopefully enable people to reflect on their own background, experiences and worldview – and how they affect and shape how they perceive things; whether that means a photograph at an exhibition, or how they see the world around them in general.

The exhibition requires a level of previous knowledge from the visitors. But perhaps that could also be part of what the Blind Spot(s) refers to: what does someone who has no previous knowledge on the pictures or Iduozee’s work, interpret and take from the exhibition? And is the onus on the photographer to educate the viewer – or is the viewer responsible for their own education? I suspect the answer is the latter. In a world where instant gratification rules supreme, we are perhaps too used to being handed things on a platter, which seems ironic, seeing as we carry all the information in the world around, with us, in our pockets, every day.

In a way, the people looking at a photograph are also at the mercy of the photographer: they can only see what the photographer has chosen to show. But what is happening behind the photographer’s back? What things – whether consciously or subconsciously – have they not shown us?

Iduozee believes that especially in the United States, the political climate has been operating by pitting mostly poor white people against minorities. However, Iduozee finds this narrative narrow, as it overlooks the middle-class and upper-middle-class people who benefit from racist and unequal structures. Racism is not just perpetuated by poor white people. The narrative that suggests this, is classicist and allows the middle-classes to feel superior and to distance themselves from far-right rhetoric and ideology.

“During the summer of 2020, many of the imagery we saw from the Black Lives Matter protests were dominated by photographs of conflicts, in which anti-racism protesters clashed with both the police and the far-right. However, these images only offer us a glimpse of what the movement is really about. I did not want to buy into the narrative of showing what everyone expected to see, as I think it only emphasises a narrative of division,” Iduozee explains.

Whose blind spots?

Iduozee wanted to portray a different kind of reality. He made the conscious decision to leave certain things out of his images and therefore influenced the narrative which he was creating of the scenes he was showing. And, just like all of us – his experiences and position as a black Finnish man – most likely shaped the way in which he portrayed his subjects. “In my personal work, I try to expand the ways in which we understand blackness by challenging the traditional framework of its visual representation and by telling the stories of people that are often ignored. I think it’s crucial for us to understand the ways in which narratives shape our understanding of reality. We also have the power to re-create those narratives and create a platform for the people whose lives have been affected by reductive and simplistic portrayals,” he states.

This is all fairly self-evident to me, a black woman who has lived her whole life in majority-white countries. I am aware of my many privileges and try to tread as mindfully and carefully in this world as I can, so as not to step on the toes of those who are less privileged than me. But how differently from someone else am I interpreting an image of a black man who is standing in a basketball court in the rain with a naked torso and a nipple ring, for example? How do my thoughts about black masculinity differ from someone else?

How do my lived experiences, skin colour, socio-economic background affect how I perceive and interpret things? How do they affect how I relate to other people?

Blind Spot(s) is an exhibition about structural racism. Before seeing it, I wondered: how does one capture something like structural racism in images? How do you even begin to portray the hidden, but oh so tangible power structures, and the pillars upon which our society has ultimately been built upon? How do you encapsulate in a photograph something that affects us, black and brown people, all over the Western world to this day? But I now realise that a big part of the exhibition is the viewer themself. The photographs are a central part of the exhibition, yes – but I feel like Iduozee has turned the spotlight on the viewers. Those who feel the impact of structural racism live with it every day. We cannot hide from it, and it is a shadow that follows us no matter where we go. Only those who benefit from it are able to close their eyes and go about their day pretending like it is not even a thing.

It feels tiring that, even in 2021, there are artists and academics who are still having the same conversations over and over again. It is frustrating that we are still spending so much time on the very basic concepts of privilege and the power each of us holds over others who are less privileged. And because we are having to do it in very clearly defined ways (so as not to be perceived as being aggressive or angry), it feels like this journey of education will take some people a lifetime.

The many privileges we hold

Finland prides itself as one of the most equal countries in the world, and we are quick to remind people how we were the first country in the world to give women the right to vote, for example. But there are plenty of unsavoury things we are also top of the world at, like domestic violence and racism towards people of African heritage, for example.

In 2018, the Being Black in the EU study found that black people are disproportionately affected by racism in Finland and that Finland is one of the most racist countries in the European Union. The study and subsequent report by Finland’s Non-Discrimination Ombudsman detailed how people of African descent in Finland face discrimination throughout their entire life cycle: from daycare to school to higher education, to the housing- and job markets.

The Black Lives Matter movement of 2020 sparked conversations around race also in Finland. A public petition, organised by mainly BIPOC people working in the arts sector in Finland, was sent to arts institutions across the country to “encourage art institutions to actively work against racist and discriminating structures”. Many institutions – including The Museum of Photography of Finland – pledged to do better, and released statements on the “anti-discrimination and anti-racist measures” they were suddenly committed to undertake. One does wonder why it took a call-for-action for the institutions to react, and what concrete changes have been made to tackle problematic approaches and structures within their spaces, as well as the overwhelming whiteness of the art scene in Finland – or whether it remains just lip service. It remains to be seen whether promises full of PR fodder turn into something tangible, or whether it is simply performative.

A lot of the time, it feels like the conversation is still barely scraping the surface in Finland, and it is often black and brown people who bear the brunt of the emotional work that goes with understanding racism and inequality. On top of our lived experiences, we are often the ones who have to coddle white people’s feelings and ease them into realising that whiteness is a problem.

As author Reni Eddo-Lodge wrote in Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race, a lot of white people still grapple with the fact that not everyone experiences the world in the way that they do. Similarly to Eddo-Lodge, perhaps Iduozee is also refusing, as an act of self-preservation, to engage further with the audiences of this exhibition. “I’ve done my part. Now it’s time to do yours,” I can almost hear him whispering.

I feel like I now understand exactly what Iduozee is referring to with Blind Spot(s). I am painfully aware that not everyone is as informed on their privileges and how that affects them. It is quite apparent that Iduozee’s exhibition is not really meant for me. It is not meant for people like us. It is aimed at the white people who still choose to live in a bubble, and refuse to accept the fact that things like structural racism, anti-blackness and white privilege are real-life things, and that they are complicit in upholding these structures.

People are only just beginning to be okay with saying they can see how the power structures in our society affect marginalised people – but no one is admitting to participating in the marginalisation. In the Finnish language, we now have a fairly established term ‘rodullistetut’ (racialised), but no one is wanting to accept responsibility in the act of racialisation. ‘Racialised’ is not an identity; it is something that is done to us. It is not something passive that is happening in the world; it is something that is done actively, whether through tangible acts, or the more hidden implicit bias.

Anti-racism work is not something you can dip in and out of. I see it as an active way of being, of existing. It’s something you either are or are not. The summer of 2020 ignited a fire in a lot of people. But many of us had been conscious of the smouldering embers our whole lives. Overnight, it seemed as if the rest of the world had woken up to the fact that the whole house was on fire. It was exhausting and exhilarating. But it is apparent that we still have a long way to go before we are able to put the fire out. It feels tiring that, even in 2021, there are artists and academics who are still having the same conversations over and over again. It is frustrating that we are still spending so much time on the very basic concepts of privilege and the power each of us holds over others who are less privileged. And because we are having to do it in very clearly defined ways (so as not to be perceived as being aggressive or angry), it feels like this journey of education will take some people a lifetime.

Racism is a problem created by white people, and it feels unfair that black and brown people are even having to put in energy into talking about it when it should be white people who are having conversations about it. But, nevertheless, I for one am very thankful that some people, like Uwa Iduozee, still have the strength to gently shake people into action.

In order to truly drive change, we have to own up to the power we hold over others. The media has a responsibility in shaping the world around us. What kind of stories get told if all the people who are doing the telling look the same? The narrative that is carved about black and brown people in Finland still today is very narrow. In many ways, it feels like it is easier for us to distance ourselves from the issues that are happening here by focusing on issues elsewhere.

Despite Iduozee’s exhibition focusing on the United States, I hope people will not make the mistake of thinking that the dangers of far-right rhetoric, tragicomic presidential elections, gun-toting white people and anti-Blackness and racism are just things that happen across the Atlantic ocean. Often it is easier for people to understand how structural racism affects black and brown people in the United States while failing to see that it is also how the society works in Europe and that Finland does not operate as a separate entity from the rest of the world. We all have blind spots; things we are unable to see because maybe we are too close to the issue itself.

Uwa Iduozee, 2020

Uwa Iduozee, 2020