Video still from Diaspora Mixtapes

Milka Njoroge is a researcher and writer whose work focuses on how black people in Finland make space through various forms of cultural production.

(or an analysis of what it means to politicize the visual)

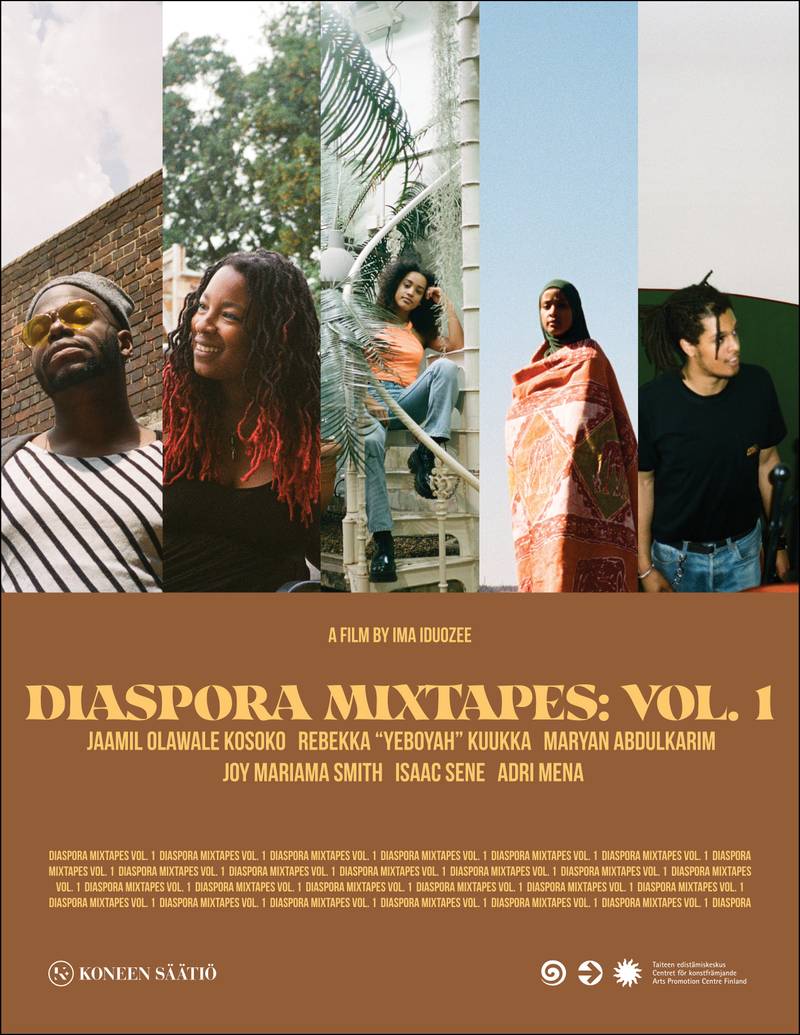

Diaspora Mixtapes is an art-house documentary that portraits artists, activists, entrepreneurs and intellectuals around the Diaspora. The first part of the series, Vol.1, was filmed in Johannesburg, Bergen Stolzenhagen, Negril and Helsinki during 2019.

The portraits consist of autobiographies and statements that highlight the diversity of black cultural identity in the contemporary African Diaspora. The first part of the series features Jaamil Olawale Kosoko, Rebekka “Yeboyah” Kuukka, Maryan Abdulkarim, Joy Mariama Smith, Isaac Sene and Adri Mena.

Directed by: Ima Iduozee | Duration: 14 min. | Language: Finnish and English | Subtitles in English

Ima Iduozee’s Diaspora Mixtapes is unmistakably part of the black expressive culture. It is a geographic film, moving audiences across different spatial scenes to tell the story of the black diaspora. However, Diaspora Mixtapes tells the story of encounters with music and film that are not rooted in a single location but instead marks the geographic entanglements that produce black subjectivities. While geographic locations remain unnamed, it is crucial to situate Diaspora Mixtapes through a spatial lens that thinks through the textual and social aesthetics which yield specific kinds of self-fashioning enacted by black people. Importantly, Diaspora Mixtapes joins other black filmmakers to produce counternarratives that consolidate black expressive cultures through intricate and interrelated histories. Space, and specifically the outdoors, becomes a site of improvisation, unexpected alliances, and contradictory sensibilities. Diaspora Mixtapes joins other Finland-produced films such as Kelet (2020) to explore a localized story of black presence in Finland entangled with the story of the global black diaspora.

In this piece, I explore the interrelatedness of visuality, black displacement and black diaspora. Diaspora Mixtapes makes apparent the efficacy of visual representations as an artistic genre that implicitly addresses questions of border regimes, queer belonging, and self-representation. Furthermore, Diaspora Mixtapes exemplifies the contemporary inclination to make visible black cultural exchanges.

As a queer black man, Jaamil Olawale Kosoko gives commentary on his encounters with “black culture in a deep way,” the deliberately grainy camera follows his movements, exposing the audience to the landscape, including storefronts, rundown buildings, and black figures walking the streets. The geographic location is unknown to the audience, but a clever eye can glimpse some stores’ names and establish that we are in a city on the African continent. Correspondingly, Jaamil’s story reveals details of the death of his brother and the psychic trauma precipitated by this incident coupled with his encounters with anti-blackness. His story articulates the kinds of violences that black people experience under the intimacy of colonial regimes of racial and gender hierarchies, or what Jaamil refers to as “state-sanctioned murder and brutality” that is a characteristic of the paradigmatic project of European modernity. The omnipresence of death does not foreclose black futures; it also engenders liberatory practices that engage in the critical labor of freedom. Nevertheless, these incidents coexist with Jaamil’s coming-into-blackness story, accelerated by his time at the Museum of African American History in Detroit at fourteen years old. These incidents-the time spent in Detroit and the encounters with modernity’s death-dealing practices-reflect the inherent contradictions of what Katherine McKittrick calls “black livingness”. In this regard, Iduoezee’s cinematic work must be read as not capturing the neoliberal trope of resilience but the brutal contradictions that black living is forced to reckon with. As Jaamil aptly puts it, encounters with antiblack violence do not force him to foreclose possibilities, they expand his vision, they allow him to reach for what Ashon Crawley calls “elsewhere” to invest in the possibility that new modes of being are on the horizon.

An unmissable dusty road lingers on the screen, marking the transition to a different geographic location. In this scene, the Finnish artist Rebekka “Yeboyah” Kuukka metaphorizes her story as a flower. “In the middle of the city that pushes its way through the concrete,” she continues, “invisible bandages on her body match the tone of her skin like they were custom made just for her”. Here, metaphors tell the story of black life in Finland. A story that finds its way into the contradictions between hypervisibility and invisibility experienced by black people in Finland. In this iteration, black Finnishness is quiet and unremarkable, yet the trauma of this oscillation is what marks Rebekka’s words. Rebekka’s desire to reclaim space on her terms, “allowing transparency. Growing and braking. Reaching for sunlight…forgets, wakes up, not remembering a thing” gestures suspension in limbo that black people have to endure. But how does one misremember the pain? Certainly, Rebekka’s narration echoes the contradictions of living in the face of the antiblack violence experienced by many black people in Finland and quite possibly the modes of neoliberal disciplining that demand that black people continuously engage in acts of gratitude for the benevolence of the Finnish state. Gratitude is folded in resilience narratives, folded in the mythologized strong willingness of black people, and hence captured on film as the specific relation to a brand of Finnish exceptionalism that sustains itself on this threshold.

The mundanity of black life is not a state in constant opposition to an essential, white Finnish subject. It is the place where black livingness is enacted through practices that humanize and enact other modes of being human. Modes that are open-ended and without guarantees.

The texture of Diaspora Mixtapes and its sensibilities are in conversation with independent filmmakers of the 1990s, produced by independent filmmakers from the U.S. not only is the audience inundated with the diversity of black diasporic narratives, space and place become the hallmark representations of the fraught relationship to blackness. While the discourse of representation continues to be a point of deliberation in Finland, I shy away from assigning Diaspora Mixtapes a positive or negative analysis of representation. Here, the work of Kara Keeling is instructive in the way it impresses black audiences with a politicized look. One that does not merely seek an authentic black experience but, more importantly, reckons with the contradictions of the lives of black people in Finland – the reserve army of labour that is relied upon for the continued longevity of the Finnish welfare state, the brutal arithmetic of anti blackness that manifest themselves in the treatment of Finland’s black population, the psychic wounds deposited by encounters with anti blackness, the unwillingness to contend with antiblack violence, et, cetera, et. cetera, et cetera. Additionally, I also want to note that filmic representations cannot ameliorate the dispossession experienced by black populations. Neither have the benevolent seductions of the welfare state greatly impacted the material conditions of black people in Finland more generally. In the past three years, the Finnish public has been made aware of certain spectacular brutalities presently experienced by black people owing largely to the interviews conducted with Black-Africans for 2018 Being Black in the EU report. A report that generated mostly shock and surprise but is still a far cry from addressing antiblack violence.

I position Diaspora Mixtapes against the backdrop of the summer 2020 global uprisings of the summer that were protesting the gratuitous violence enacted upon black people. Keenly aware that the specificities of black dispossession are historically contingent and variously manifested, the push for a more sustained engagement with the manifestations of anti-black violence and efforts for a more expansive understanding of antiblack violence are seen as threats to the naturalized homogeneity of the Finnish state. This, of course, robs Finland of a politicized language that could speak to the interlocking dynamics of class, race, citizenship, and gender, leaving in its place an emboldened white citizenry that demands we pay allegiance to the benefits of the social welfare state. In addition, leaning too heavily on the analytic of representation risks slipping into what Stuart Hall calls “liberal-pluralism”, or a colorblind politics that restricts and impedes the ability to think complexly, relationally, and interconnectedly. Ima Idouzee’s Diaspora Mixtapes exposes not just black dispossession but more interestingly, the mundanity of black life, precisely where black political configurations reside. The mundanity of black life is not a state in constant opposition to an essential, white Finnish subject. It is the place where black livingness is enacted through practices that humanize and enact other modes of being human. Modes that are open-ended and without guarantees.

To theorize a black Finnish identity, therefore, is to reckon with the ways in which black Finnishness does not merely exist suspended in history as if unmoored from the history of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. Far from it. As with other modern states, the formation of the Finnish nation-state was facilitated by participation in the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism.

Elsewhere in the film, music offers a foundational way of thinking about black diasporic populations. Music is both a feature of black expressive culture and an activity that allows us to listen to utterances that express themselves in other ways. Music allows the audience to listen to the discontinuity in the narrative. The musical breaks inserted throughout those 13 minutes and 55 seconds of Diaspora Mixtapes allow us to listen more intently to conversations, to parse out belonging, memorializing, death, state-sanctioned violence, and racial and gender hierarchies. This listening is not passive. It forms the active imperative that sits with the brutalities and the radical imaginings of a radical elsewhere. This soundscape gestures both to another possibility and attunes our sensibilities to the space of transgression that is collectively founded, thus inviting audiences to consider the sonic as an embodied and collective freedom-making process. Isaac’s strum of the guitar is the conduit for this journey. The lyrics move between Finnish and English. A sorrowful sound that gestures to a longing to go back to his roots: “I’m going to see my roots, my father. No sad goodbyes. I can only learn about myself. Pack my bags and leave. This is not a place for me now, I believe”. This longing for an originary point has been theorized by Stuart Hall as “the traumatic character of the “colonial experience”” that figures black people through narratives of “being eternally fixed in some essentialized past”. To theorize a black Finnish identity, therefore, is to reckon with the ways in which black Finnishness does not merely exist suspended in history as if unmoored from the history of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. Far from it. As with other modern states, the formation of the Finnish nation-state was facilitated by participation in the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism. Finland cannot claim the position of an innocent bystander nor continue to press forward with the humanitarianism inaugurated in the early 1900s that involved the colonial mission of civilizing Africans by building schools and churches in present-day Namibia. Conscriptions to the nation-state demanded that hierarchization of human beings be made. Thus, practices of racial and gender differentiation in Finland are rooted in this ineffable history.

After a short musical interval, the camera switches to black-Finnish activist Maryan Abdulkarim. The words “no one’s self-worth should be dependent on being a model citizen” flash across the screen. Here I want to briefly explore the trap of the singular experience that has come to define the resistance against state-sponsored violence, particularly as in the case of Finland owing to the unwillingness of the general white Finnish public to acknowledge black presence, which is often coupled with shock, unfamiliarity, erasure and unspeakability. The benevolences of the Finnish welfare state obscure the grammars of antiblack violence by fictionalizing state safety as accessible to all within Finland’s borders. Individualized narratives approximate neoliberal tendencies of agency and personhood as exemplifiers of subjectivity while leaving intact the structural problematics of racism. These grounds are insufficient in challenging state-sponsored antiblack violence as they instrumentalize overcoming as a legitimate framework for (predatory) inclusion. Singular stories inadvertently produce moralizing discourses of worthy subjects and non-worthy/blameworthy subjects. Singular stories reinforce the binary of deservingness by dictating those who belong and those who are outside the so-called human register—those who deserve full access to rights and those whose access is a constant negotiation. So the stakes that I am gesturing to here are immense, not just for the hypervisible black activists, but overwhelmingly for the rest of the black population. The phenomenon of narrating a singular story must be linked forcefully to a critical analysis of racial domination, the history of colonialism, and the racist policies of border migration that constitute an integral part of the discourse on race and racism in Finland. The category of the Other is essential to the formation and legitimization of the nation-state. It is a category that transcends a singular story yet is often used to individuate immigrants by reproducing ideologies of who is a model citizen, deserving of rights and who is not. We must release our stranglehold on the exceptional single story to allow for the depth and breadth of the collective resistance to come forth. We must refuse to be hailed through narratives of the good subject and instead recognize that our struggles are transnationally interconnected and that the work of border regimes is to produce desirable subjects through racial and gender hierarchization. But this “we” that I refer to is also fraught and grapples with specificities of different affiliations. It is not a flattening of differences nor a unifying condition. Nor is it an individualizing “we” that seeks recognition in liberal humanism or one that is bound to the nation-state. We forget that “we” by attending to how the colonial logic interpellates us in various ways and to recognize the fragility and precariousness of the “we” while also glmpising the radical possibilities that can be enabled by this “we”.

The category of the Other is essential to the formation and legitimization of the nation-state. It is a category that transcends a singular story yet is often used to individuate immigrants by reproducing ideologies of who is a model citizen, deserving of rights and who is not. We must release our stranglehold on the exceptional single story to allow for the depth and breadth of the collective resistance to come forth.

The politics of deservingness is a vicious utility that fails to interrogate what Harsha Walia (2021, p. 14) calls “the expectations of gratitude, or assimilation, gestures of charitable humanitarianism […], the commodification of labour to benefit capital accumulation,” et. cetera. Therefore, we must interrogate gestures that are enmeshed with the logic of Finnish exceptionalism and white European heteropatriarchy desires.

Finland’s noticeable move towards neoliberal policies demands that we continually uphold our subjectivities in their singularity. Whereas care-cleaning work is racialized and feminized to facilitate the entry of white and upper-middle-class people to the labour market and the production of the wealth of the nation-state. We must reject the position of the exceptional immigrant who overcame unfathomable odds as this feeds the Finnish Exceptionalism and benevolence machine. For those of us who were never meant to survive, we can no longer afford to whisper from the ruins of the margins. This Lordeian call focuses our attention on the multiplicity of the collective to plot new ways to grapple with the emerging hierarchization that enclose, appropriate, and dispose of the Other. Figuring immigrants and nonwhite peoples as essential to the formation of the nation-state unmoors Finland from its exceptionalist narrative and exposes the ways in which dispossession, structures of dominance and racial capitalism are central ideologies to its construction. This Lordeian call enlivens acts of resistances by recognizing the boundedness of our struggles. Adri Mena’s work rejects an exceptionalist lense by reckoning with the history of the transatlantic slave trade and the transportation of slaves to the plantations of the New World: Her work “deals with the process of identification of the black woman in contemporary Cuban literature”. As it becomes clear, Adri’s work traces this figure through the black diaspora to identify those elements that "signify being a human ‘’ that influence these women’s appearances in Cuban literature. For Adri, the affective dimension must be explored to mine those elements that speak to the consciousness of the black women characters in Cuban literature. Adri’s relation to this archive recognizes the contradictions in their stories, their transportation as slaves from Africa to the New World. Yet, it is necessary to re-narrate their stories and explore their interiority. It becomes clear from this brief interaction that Adri’s preoccupation is not with recovery but with wanting to keep these black women alive in our memories. Adri’s work is undergirded by a subaltern undertaking, a practice for capturing the vastness of black subjectivities. A practice that anticipates complex relationalities enlivened by risk and protest to create lines of connections, contestations and struggle across black diasporic identifications.

Video still from Diaspora Mixtapes

Video still from Diaspora Mixtapes

Poster for Diaspora Mixtapes Vol. 1