Uzair Amjad (b. 1989, Sahiwal) is a Pakistani filmmaker, multimedia artist, and writer based in Helsinki. He holds an MA in Visual Culture, Curating, and Contemporary Arts from Aalto University, Finland. Amjad’s works borrow greatly from his original training as an image-maker and from oral traditions of storytelling.

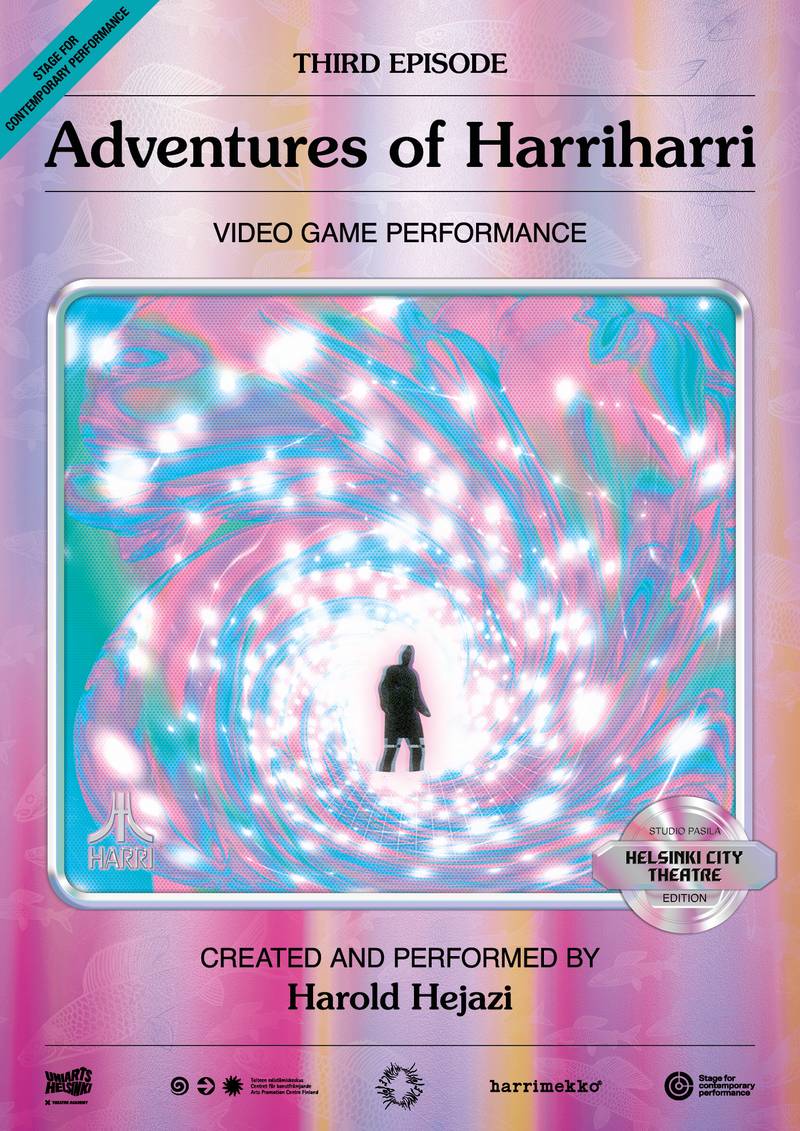

A retro-styled video game menu appears on the screen against the backdrop of a speculative kind of space that one might associate with dream-like vistas. There is a sense of a landscape here. Sparkling shrubs and trees are suspended in the air. Two rainbows mirroring each other can also be seen, and both are opaque with distinguishable outlines. A bent, out-of-shape figure with no discernable hands and smudged facial features stands in the middle of this groundless landscape. We can’t read more into the character at this point. It possesses cloud-like formlessness that escapes definition. But what we can tell about this character is that it has a name. The game’s title that hovers over the character’s head reads “Adventures of Harriharri”. An inversion of the known world is on display here, exuding the sense that this game will dream of a new world, one without pain?

Another smaller screen pops up in the top left corner of the main menu, a picture in a picture. In it sits the artist Harold Hejazi. Harold’s attire matches Harriharri’s; he also has the same moustache and a similar hairdo. The artist gasps in disbelief, surprised by the human body he finds himself in. At this point, it becomes apparent that I am encountering two congruent modes of Harriharri at once. The first one is Harriharri, the game character in the digital realm. The second Harriharri is the alternate persona of the artist who channels, expresses, and shares digital Harriharri’s experience. The character acquires more definition now; it becomes more familiar to me. Harriharri is brown like Harold, Harriharri is brown like me—representation, yo!

In recent years, the picture-in-picture (PIP) feature has been quite a hit with live video game streamers. Live game performers utilize it to entertain audiences with comedic and satirical commentary over the course of playing through a game. The audience of live game streams also participates in these performances, expressing their approval or disapproval of the gameplayer/commentator’s performance through visual emoticons, memes, and gifs. But here, as Harriharri begins a new game and addresses an audience from the PIP, he is received by a roaring crowd. This feels like a concert is about to commence in front of an audience closer to the spectacle. The mixing of digital and spatial technologies is at play here. In this live game performance, individual inputs from spectators separated by physical distance are displaced by a collective participatory phenomenon, eliciting the theatrical.

Part of Harriharri’s agency lies in his words; his rap formulations open up a multitude of analogies. Through unfolding a language of gestures and names, supplemented by electronic music, the audience is lured into repeating after Harriharri.

The game performance trilogy begins by introducing Harriharri’s agency in this new digital world. The character explores the boundaries of this world and his own limits. He hesitantly walks towards the game assets and looks around to see if he has any company. We only see the back of the digital character’s head as he moves around in the third-person view. The audience and Harriharri experience this new world together at the same time through the same perspective, as if they are one. To accentuate our oneness with Harriharri, we are made privy to his emotional status through a rap performance by Harriharri’s human incarnate from the commentator’s booth. Part of Harriharri’s agency lies in his words; his rap formulations open up a multitude of analogies. Through unfolding a language of gestures and names, supplemented by electronic music, the audience is lured into repeating after Harriharri. Rap here serves a pedagogical purpose, and it begins to share space with the voice inside our heads, triggering a conversation about the Harriharri experience and teaching us about his world and circumstances.

Still unfamiliar with his surroundings, Harriharri tones down his frisky movements and crouches as he heads toward the next room. Harriharri raps.

Crouched! Crouched is my position.

Wouldn’t wanna go too far too fast

Goin slow is just the right speed

Gonna make it somewhere, yes indeed!

Yes, Crouched! (Harriharri smiles ironically)

This rap sequence draws instant laughter from different sections of the audience. I chuckled as well. The audience’s laughter varied in type and extent and lasted longer in some segments than others. I wonder if we all laughed for the same reasons. I laughed because I know ‘crouched’ is precisely how a brown person feels inside when entering new environments.

By combining wordplay with electronic beats and game mechanics, Hejazi activates fantasy’s critical function to give the audience an insight into alternate realities.

Harriharri is looking for new words to start conversations and new ways to fit into Finnish society. From out in the open somewhere in Finland, he gets a ride from a spirit reindeer. And in a blink of an eye reaches a mall in Itakeskus in Helsinki. This dream-like switching between times and spaces here disintegrates the linearity of experience, but it does so informed by a universal collective impulse of wanting to be included, integrated, and represented.

We are in the outdoors now, on a snowy day. A white man, twice the size of Harriharri, catwalks towards him, strikes a pose, and welcomes him to Finland, “Hello Harold”, he says in a tipsy fashion, and then leaves before Harriharri gets to say anything in return. A queue of relatively sober people waits ahead, some dressed questionably in summer wear. Harriharri enthusiastically, like an immigrant trying to make a good first impression, tries to strike up a conversation with the locals. But his efforts are only met by Nähdään, Heippa, Moikka, Moi Moi, and the best he earns is a no niin, followed by a Moi Moi!

Harriharri is looking for new words to start conversations and new ways to fit into Finnish society. From out in the open somewhere in Finland, he gets a ride from a spirit reindeer. And in a blink of an eye reaches a mall in Itakeskus in Helsinki. This dream-like switching between times and spaces here disintegrates the linearity of experience, but it does so informed by a universal collective impulse of wanting to be included, integrated, and represented. Itakeskus, known as Itakuskus on the streets, is a neighbourhood in Helsinki that takes its nickname after the immigrant communities that live here. It’s not clear if the immigrants or the white folks coined the nickname. Nevertheless, the diverse inhabitants of Itakuskus have lovingly taken this nickname in their stride. Jokes and satire are a rampant form of expression and inclusiveness in this neighbourhood. The play on words in this part of the city does not sit outside history or contemporary socio-political circumstances. In fact, the propensity and astuteness of this wordplay are motivated and shaped by these same conditions. It’s this particular style of play that Hejazi, who used to live in Itakeskus himself, has rendered his game with to make it operate against the status quo.

Harriharri comes across Marimekko next. A Finnish clothing company credited with making “authentically Finnish” designs, whatever “authentically anything” means these days… But he’s put off by the prices. When you are an artist and an immigrant artist at that, you only dare to Marimekko if you somehow win the lottery or then land a multi-year artist grant, odds of the latter being less, of course. Harriharri decides to try his luck nevertheless and apply for some artist grants. Now we all know how this grant game works. Although the rules of this game are still unknown, its results are not that unpredictable. Every year, less than 7% of the total funding for the arts awarded by public and private funding bodies is given to artists with immigrant backgrounds. If I were to quote exact numbers from the recent statistical reports on grant awards, even more, discouraging figures and problematic categorization of artists would come up. I implore anyone who disagrees with my approximation to check out CUPORE’s latest report in length and bum yourself out.

Some voices from within the art scene have often objected to complaints about the lack of funding for artists with an immigrant background by stating that the percentage is directly proportional to the number of applications sent in by artists with an immigrant background. Well, when did the playing field become equal for everyone in the Finnish art scene for us to start considering ratio formulas out of a 9-year-old mathematics exercise book to give out grants? Finnish society does not facilitate equal work and participation opportunities for all. It vociferously discriminates against residents based on their ethnic backgrounds, leading to highly unfavourable living conditions and resulting in inaccessibility to opportunities in society.

Here’s a brief insight into what it means to be an immigrant artist in Finland. Most immigrant artists have no chance of landing a job in arts and cultural institutions in Finland, as advanced Finnish and Swedish language requirements gatekeep these positions. Many struggle to establish an entrepreneurial practice due to widespread xenophobia. Those who manage to make it work for a few months are made to regret it once they hit a rough economic patch and an even rougher abyss in TE services (unemployment office). Furthermore, non-EU immigrant artists in Finland do not have equal access to social welfare. They are often pushed into seeking zero-hour work contracts without accident insurance in high-pressure restaurants, food-processing units, construction sites, and cleaning companies. Although these industries involve teamwork and constant communication, language is not an obstacle here as these jobs are not sought after by the locals. Struggling to find regular working shifts to earn 1300 euros a month, immigrant artists have to put the maintenance of their artistic practices and their mental and physical health on hold, or else the immigration office orders their deportation. Such living conditions make it impossible for these artists to learn the Finnish language, effectively authorizing their perpetual state of struggle.

When arguments about proportional shares are brought up in conversations about immigrants, a part of me supports that “logic”. We should consider direct proportionality in a historical context. Start by applying it to calculate reparations from colonial settlers and their imperialist collaborators – they, together, are responsible for most if not all global inequalities, of which exploitation of immigrants is also a consequence.

For how many more years will the funding bodies hide behind their less than 7% tokenism funding for immigrant artists? Entire electoral campaigns in Finland are planned around the question of immigration. Shouldn’t more visibility for artists with immigrant backgrounds be facilitated? Shouldn’t the public encounter their work, and understand the plethora of their concerns, ambitions, and aspirations in and for the Finnish society? Tragically the public gets to hear about immigrants from Nazi party leaders instead. There’s a systemic enclosure of immigrant perspectives in the Finnish society that has led to an increase in racism, sexism, and other forms of intolerance here. Competition-based funding models are just damaging for community formation at all levels. These models contradict the purposes stated by the funding bodies every year, defeating their goals of increasing inclusiveness, equality, and equity.

It’s incumbent upon the administrations of arts funding bodies—those with monthly salaries, indefinite contracts, and no looming deportation—to consider the complexities of an individual’s identity in their decision-making processes. They need to create more sophisticated grant models with a central focus on sustainable support for marginalized sections of the Finnish art community. It’s about time they consolidated their slogans about diversity into their working ethos. To create a new framework for awarding grants, funding bodies must engage with working groups comprising diverse art workers who advocate for the representation of marginalized artists and equality and equity for all. They must make their working processes transparent and continue iteration of their policies through long-term collaborations with art workers from the art scene.

And so, like many others, Harriharri fails to succeed at the game of grants, and in despair, he jumps off the edge of this game’s world. But Itakuskus comes to his rescue, providing him with the ground to land on and affordable clothes by “HARRIMEKKO”. Hejazi uses the character’s self-referentiality to add to the jokes’ potency while also opening up his fundamental artistic/political procedure to the audience. Itakeskus and its all-inclusive fertile humour and satire are utilized again in locating and ridiculing centres of power.

Would they protest only when their funding is endangered? Would they ever come together and protest the discrimination immigrant artists face from the labour market? Would they demand diversity and inclusiveness in their workspaces? Or protest the deportation of non-EU art workers, their allies, and friends who have contributed to Finnish art and culture for years?

Harriharri receives a message alert! He is invited to perform his live game performance at Ateneum! One of the three premier art museums that collectively form the Finnish National Gallery. Important to note in this message is that this facilitation comes at the behest of UrbanApa, a community created by art practitioners with a diverse ethnocultural heritage who have a special focus on furthering anti-racist and feminist perspectives. There are a handful of such initiatives in the Finnish art scene, fighting racism, advocating for equality and equity, and facilitating inclusion. But they are mostly the work of artists with immigrant backgrounds.

But why do the already marginalized, the ones who get less than 7% of the funds, have to carry the burden of representation? Why is it that most of the beneficiaries of the other 93% remain unbothered about facilitating inclusiveness in the arts? We recently saw the entire arts community come together and protest the proposed cuts in funding for the arts and cultural sector. These cuts would have affected the whole art scene, irrespective of whether you are a non-EU artist, an EU artist or a Finnish artist. The protestors received all the coverage from the media; they were in the papers, on TV, and everywhere on social media. It was great to see the community displaying solidarity with each other and registering their disapproval of austerity. This got me thinking, though. Would they protest only when their funding is endangered? Would they ever come together and protest the discrimination immigrant artists face from the labour market? Would they demand diversity and inclusiveness in their workspaces? Or protest the deportation of non-EU art workers, their allies, and friends who have contributed to Finnish art and culture for years? One of the primary reasons why our institutions are not willing to change at a greater speed, it seems, is that the art scene itself is not demanding them to change in numbers.

It also needs to be pointed out here that any solidarity in action with marginalised communities is not an act of favour to them. Instead, it is an act of upholding the principles and policies that one would like for themselves. It is a push against ultra-nationalist, racist, misogynistic, and essentially fascist ideology. Fascism may instrumentalize identity politics, to begin with, making you feel like it’s on your side, but in time it will not differentiate between gender, colour, and creed. It will come after you sooner than you think. Hint*: It’s around the corner when your education and healthcare are on the verge of privatization. So let’s curb that white saviour syndrome as well, shall we? And stand side by side while acknowledging that this battle against oppression is a mutual struggle. It is urgent now, more than ever, that we, the diverse communities of the Finnish art scene, realise our prejudices and privileges. We can propel our institutions into tangible change by becoming conscious of our individual and collective capacities.

Next, up in his adventures, Harriharri encounters the supreme leader of the True Finns party, his wickedness, Jussi Halla-Aho himself, portrayed as Nosferatu from the eponymous 1922 German film. Apart from its many cinematic accomplishments, the film is also known for contributing to the list of 20th-century anti-Semitic stereotypes. Nosferatu was depicted as an emaciated figure, pale, dressed in a black coat and a scalp that’s the shape of a Yarmulke, an alien here to suck all the blood out of the white Christians. A distorted image of “the other” fashioned by “the self” that stares into the mirror, a figment of Nazi imagination. But the Nazi imagination has evolved since. “The others” have more melanin in their skin now, a beard occasionally, they devour couscous, and legend has it, “They take away Finnish people’s jobs and their women." This Nazi rally chant presents half of their arguments against immigration and summarizes the problems with their ideology in full. Since Harriharri fits this “new other” profile, he too is told by Emperor Halla Aho to pack his bags and get going.

Unnerved by this encounter, Harrharri heads to the Finnish countryside to seek some calm and peace. He has been in Finland long enough; he is familiar with its sounds, sights, and signals in ways unknown to others, even to himself. After all, the familiar has a secret magical side too. Here again, Hejazi, through a fictive gesture, a dream sequence in the game, pulls Harriharri and the audience into new modes of thinking, sensing, and drawing connections. In this dream within the dream, Harriharri meets a fish that speaks and reveals to him secrets of the city within the city, an illuminated form, Harriharri’s city.

Will this game performance trilogy eventually dream of a world without pain? That remains to be seen in its next and final rendition. But what I may add in this regard is that dreams shape history, but they are also shaped by it. Dreams are floating expressions of the real world, with their desires, anxieties, absurdities, and horrors. Their world is as much our world as it is our world’s inversion, and it is this tendency of dreams in which we can discover their use. The Adventures of Harriharri is one such ‘other-worldly’ space where we can experience each other’s dreams. The live game performance uncovers the overlapping of territories, the unsettling of institutions, and the linking of languages and sites of exploitation. It investigates what migration can teach us about contemporary forms of community and encourages us to search for that which goes beyond them.

The first episode of ‘Adventures of Harriharri’ was performed in Urban Apa x Atenuem at Atenuem’s art museum (2020), followed by the second episode in the exhibition titled Reciprocities at Vantaan Taidemuseo (2021). The final episode of this live game performance now takes place at Helsingin Kaupunginteatteri, Studio Pasila, this May on the 19th, 20th, and 21st.