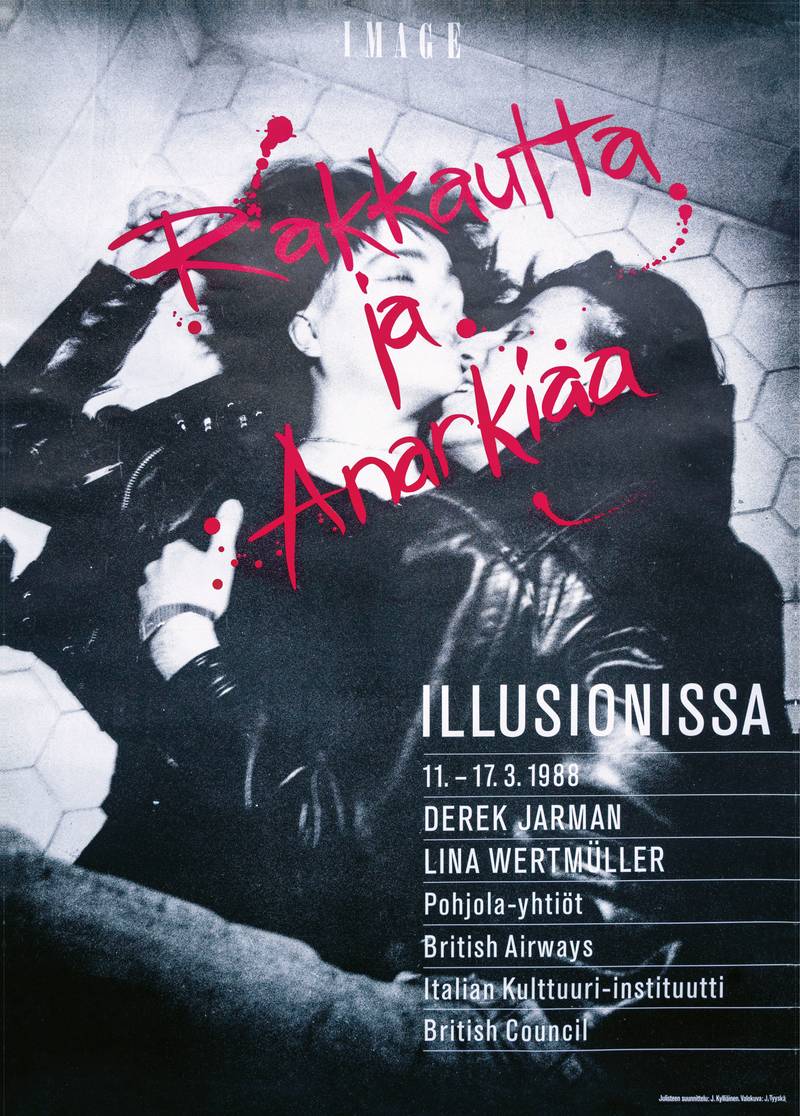

1988 L&A poster designed by Jussi Kylliäinen

Kazu Ahmed is a resident of East Helsinki. He is researching for his doctoral degree at the University of Helsinki and is a practitioner of participatory visual methods (PVM) for research and social change. He has worked with a wide range of communities helping them create their own visual narratives about their worlds. He studies the application of such a methodology for dialogue, peacebuilding and reconciliation in ethnic conflicts.

I am a consumer of films, and film festivals are great fodder for this cultural hunger. But an attempt to write a review of the annual Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy (L&A) made me realise how limited my experience was regarding the cultural and political lives of such an institution.

This piece, consequently, is my exploration of film festivals as someone interested in the arts, who follows political and cultural processes, is curious about the worlds portrayed in films, and one who likes film festivals and what they offer but does not understand how they work. It is an ontological conversation with myself about cultural processes, the creative industry, and how and when these intersect with the lives of a city resident like me.

When I started writing, complete details about the 2022 edition of the festival were not available online, and I could only browse through information about the previous years. I eventually saw the 2022 catalogue and the impressive selection for this year. While most films would be shown past the deadline for this piece, I was fortunate enough to make it to a special screening as part of the festival. Much of my exploration is through looking at available information on L&A and discussions with a range of people about identity, politics, representation, power and dialogue in film festivals, including the festival organisers and some members of the audience I have met. This review is also a presentation of their opinion.

Exploring the world of film festivals

Pekka Lanerva is the Artistic Director and one of the earliest organising members at L&A. Fondly remembering the festival’s beginnings; he said it was almost an accident. “The first event in 1988 was created by people involved with the Image art magazine and event organiser, which they wanted to expand to films /cinema,” he says. The idea was to give prominence to the marginal, which at that point was an adequate and appropriate cultural representation of gay and female filmmakers, as well as to take a position against censorship.

Anna Möttölä, Executive Director of the festival, joined in. “The festival emerged from a need of what Finland was in the 80s. It was culturally a much more closed-off society and country than it is now. One could not bring stuff (cultural products) from outside. From that perspective, the festival is about bringing world cinema to Finland,” she said. In the spirit with which the festival was founded, it took its name from Film d’amore e d’anarchia, a brutal and compelling saga of love, politics and the margins set in Mussolini’s fascist regime.

Lina Wertmüller directed the film, the first female filmmaker to be nominated for Academy Awards; five of her films were screened during the first edition of the Love & Anarchy Film Festival in 1988. The 2022 edition pays homage to Wertmüller by screening her 1975 classic Pasqualino Settebelleze (Seven Beauties).

Film festivals are unique in that they perform multiple roles and are visibly different from the cinema in scale, form, and character. Marijke de Valck, a researcher of film festivals, calls them sites of passage – a space “so important to the production, distribution, and consumption of many films that, without them, an entire network of practices, places, people, etc. would fall apart.”

With a mandate to promote film culture in Finland, L&A has acquired a unique reputation and, consequently, a respected position over the years. A look into the partnerships of the festival bears testimony to its significance in the cultural milieu of Finland. Many people I spoke with eagerly await their annual pilgrimage to this event. This position, say Anna and Pekka, allows them to offer the event as a launchpad for those beginning their careers in the creative industry.

“Love,” says Pekka, “is something that unites.” It is an emotional bond, he opines. And anarchy is something that breaks the predominant order. “The festival is not just about art; it is also political,” adds Anna. A quick look at L&A reveals the cultural and political identity the festival has created for itself. This year, for instance, has a selection on Ukraine, evidently in solidarity with the country in the context of the Russian invasion. The festival’s webpage also very vocally demands the release of Iranian filmmakers Mohammad Rasoulof, Mostafa Al-Ahmad, and Jafar Panahi. According to Anna, the curation reflects subjects of critical immediacy to the world; this year, it is the climate crisis.

I could see a lot of love. But I was still trying to find the anarchy that breaks through and what it breaks through. I wondered if I should write about the positionality of the festival in what can be termed as its cultural intervention into events and processes that affect us today.

As a venue that nurtures and celebrates films and cinema, a film festival also acts as a collective political space where different political positions interact—those of the filmmakers, the audience, and the festival organisers. It is a process of togetherness reflected in all aspects of a festival geared towards an audience viewing a specific presentation, engaging in what academic Julian Hanich calls ‘a collective cinema experience’. This experience may be prevalent at a regular film screening in cinemas. What makes it different in a festival is the overarching identity that a festival creates for itself and the expectations that it generates.

Long-time attendees of L&A, whom I spoke with during a special screening at the festival, said they came to the festival because of the political content in its films, which was not available in cinema normally available to film enthusiasts. The political content also features categories such as ‘African Express’, a selection of films in L&A that started in 2019. Since 2021, this selection has been curated in collaboration with Think Africa, a social and cultural organisation working with the African diaspora in Finland; and the Ubuntu Film Club, a community-driven cultural initiative.

As we talked about politics in film festivals while sitting by the pavement in Kallio, Wisam Elfadl, a cultural producer leading the Queering Islam project, indicated that even within a festival and all that it comprises, including the audience, the politics vary widely and are intersectional. It is also performative, particularly when it comes to a category such as African Express.

“It is political when you enter a film festival as a non-white person. It is like, ‘there must be something when she is here! We chose the right film! There is something, perhaps a layer, that we should understand if she is here!’ When entering such spaces, it is always a set of performances (of identity) because the whole setup is created with a class to it. Even if you just want to go and watch something, it is already performative,” she says. In that context, “I, as an African, am on stage, and the spotlight is on us,” adds Wisam, and it is not necessarily the desired position.

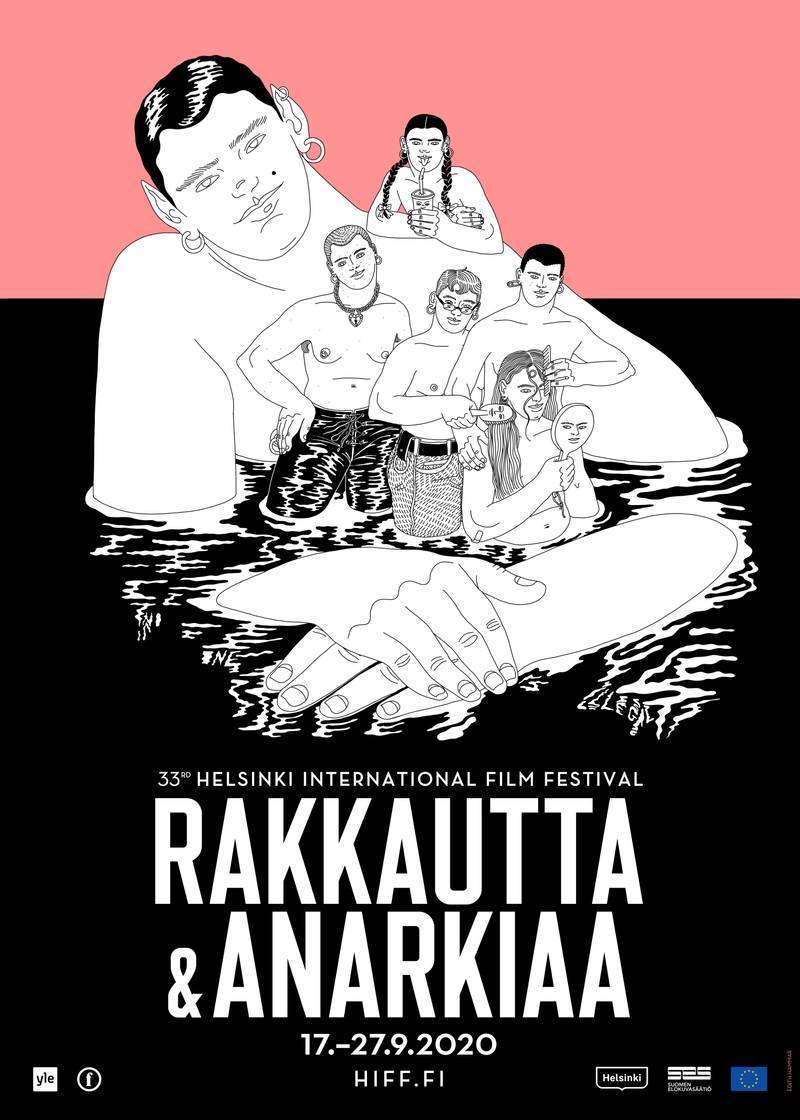

2020 L&A poster designed by Edith Hammar

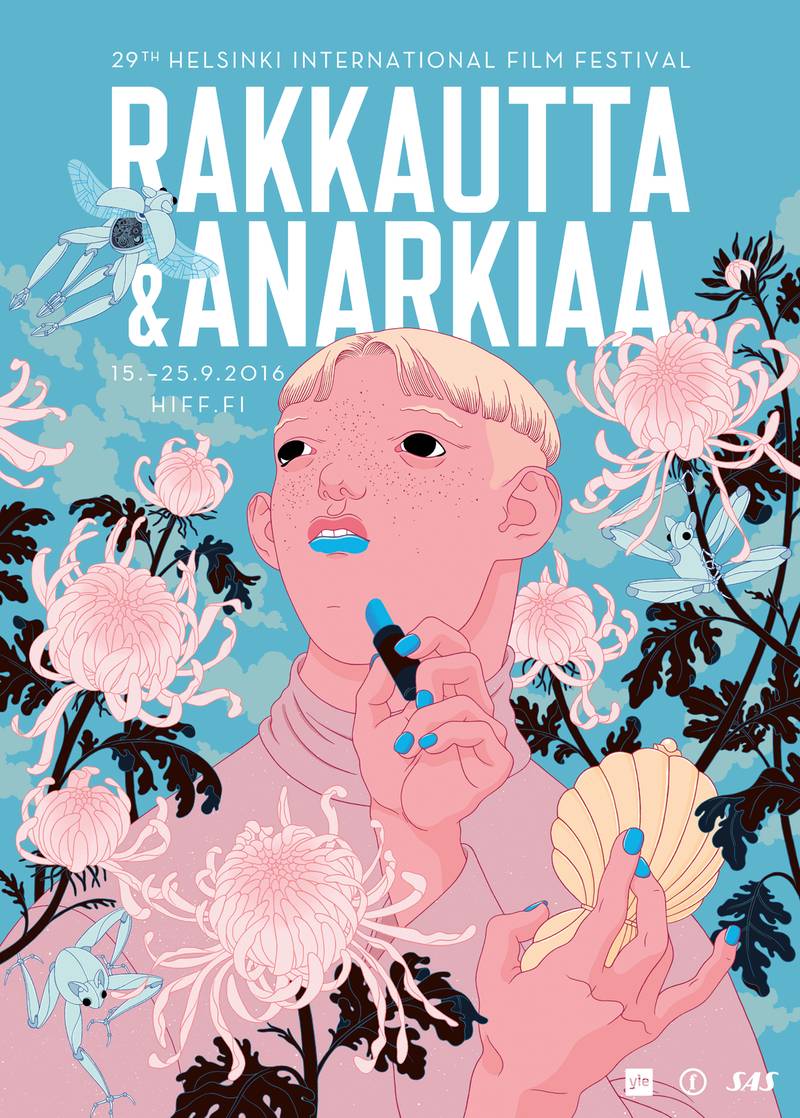

2016 L&A poster designed by Eero Lampinen

Navigating categories

My unease with identities framed in categories was sparked when I noticed the eminence of the African Express selection in 2021. According to an article featured on the website, these films explored freedom from the perspectives of migrants, refugees, and prisoners. In relation to the political geography of Africa, the films and filmmakers were associated with Tunisia, Mali, Egypt, Ivory Coast, Algeria, Kenya, South Africa, and Morocco. Five of the eleven films collaborated with European countries, and one with Canada. One would immediately notice that a considerable chunk of geographical Africa and its creative industries were missing.

In terms of content, four out of 11 films dealt with the idea of an African migrant and/or refugee experience. As a film enthusiast and prospective film-goer browsing the catalogue, the repetition of the subject makes me wonder about thematic saturation. To a viewer unversed with African societies, cultures, and creative industries, I wonder if it gives a rather monochromatic view of the continent. Or a largely, if not totally, monolithic understanding of peoples, societies, and cultures related to the continent.

I do believe that narratives of trauma and coping, particularly from visual storytellers associated with those processes, make for powerful statements and can be part of what E Ann Kaplan calls “witnessing”—an empathic understanding of suffering across cultural differences with a possible healing result. At the same time, however, it also brings to my mind the word “gaze” in cinema (in this case, a European gaze), a subject that Kaplan extensively discussed.

It is perhaps the peril of taking a chance with geographical categorisation that, in addition to problems of inclusion and representation, it opens up more avenues for scrutiny as geographies are deeply associated with identities. While, on the one hand, a category may put the spotlight on and highlight creative processes associated with a region, any apparent failure raises questions about the nature of curation and inclusiveness.

Pekka and Anna agree that geographical categorisation becomes somewhat artificial, reflecting a particular framing and gaze in the festival. However, they say that the present mechanics of film festivals, in how they are organised and conducted, make it easier to work with collaborating organisations. “So we need to cut some corners,” says Pekka. Societal beliefs and structures are instrumental in creating margins which, according to Anna, L&A addresses through its films. “We are also dictated by society,” she adds.

It is perhaps my naivety and my own understanding of anarchy. But I felt rather disappointed, if not surprised, at how the dynamics of categorisations and power relations in festivals feed each other, undermining the idea of breaking through in festivals like L&A. Perhaps the answer lies in more frequent reflection, vocal and audible discussion, and emphatic efforts to level inequalities in power, now that many festivals have the capacity to intervene, having taken on the role of distributors.

While I am inclined to understand society here signifies the audience of the festival as well, I am also aware that it comprises other actors in the festival world. Does this society, with all that it encompasses, influence how categories are created? It became apparent to me that distributorship plays a decisive role in sourcing and curating films. “While there is a White gaze in the choice or curation of films, there is an element of elitism in the distribution of movies, which is also related to what is produced and distributed. Those films with co-producers from Europe have a higher chance of rising to the top,” says Vishnu Vardhani, artist and volunteer with L&A, as she problematises the power exercised by this system.

Categories can lead to confusion and create power relations that dictate accessibility in festivals. “Films and filmmakers associated with, say, North Africa or South Africa and co-produced with Europe, for instance, can be put in many festivals as they can navigate categories. From a diversity perspective, they can be in North Africa, South Africa, or Europe. But suppose you are in the Black film industry, which is totally African. In that case, they (film festivals) don’t know how to include it,” says Wisam.

She goes on to give the example of Finnish-Somali filmmaker Khadar Ahmed. She said when Khadar’s critically acclaimed The Gravedigger’s Wife was released, “in some newspapers, he was called a Finn, some called him Somali, some an Arab, some a Muslim. He could navigate through all of it. But it is difficult if you are an entirely Black production unless someone picks you up or you collaborate.”

It is perhaps my naivety and my own understanding of anarchy. But I felt rather disappointed, if not surprised, at how the dynamics of categorisations and power relations in festivals feed each other, undermining the idea of breaking through in festivals like L&A. Perhaps the answer lies in more frequent reflection, vocal and audible discussion, and emphatic efforts to level inequalities in power, now that many festivals have the capacity to intervene, having taken on the role of distributors.

That said, there are no easy answers to all these questions of funding, production, curation, and distribution in film festivals and the power relations implicit in these processes. take the example of Indonesia, where researchers R Ihwanny and M Budiman say funding and unequal collaborations with Europe are a double-edged sword. In this context, while such unequal collaboration may perpetuate a perception of Indonesia as a developing country, it also facilitates the growth of the creative industry in the country. I would be interested in seeing how much this capacity that is built is able to unshackle what the researchers call hegemonic practices of providers and receivers.

Enabling visibility

Do categories serve a specific gaze, have a performative role, provide an imaginary of geopolitical identity, or fulfill a process of political gratification? Noora Geagea is a visual artist familiar with the art world in Helsinki. “Gatekeepers in the world of art have in their minds these themes and ideas of what is relevant today, and the artist or the film needs to pass or fit these ideas. They are predetermined. It puts a subject out there but does not stir the pot too much,” says Noora. As I started chatting with more people, it was apparent that the phenomenon of “playing it safe” was reasonably well known in the Finnish art world. I believe it is also a question of comfort.

The other question is whether categorisation, while providing prominence to certain narratives, obscures other players in specific creative industries? For instance, a part of the larger African creative industry that we do not see very often is Wakaliwood. I am fascinated with Wakaliwood for many reasons, primarily for how it changes the definition of cinema from a very ground-up perspective. It is making cinema accessible to communities in the peripheries of what one may call mainstream cultural institutions and creating an entirely new cinema experience.

And it is not limited to Uganda. One can see this reconfiguration of visual culture in many parts of the Global South, where cinema as we know it is inaccessible for political or economic reasons. However, small-budget VFX-laden films from the villages of Uganda are not what we get to see at European film festivals.

To the credit of L&A, this year’s selection has Once Upon a Time in Uganda, an acclaimed documentary made by Catheryne Czubek, which will make us aware of the existence of Wakaliwood. But again, it is a high-value production by established professionals with high-end gear. Not the ragtag social production that is done in Wakaliga with a budget of a few hundred euros. Through a documentary, we are only voyeuristically engaging with the phenomenon, not experiencing the same cinema as the people of Kampala. We are bold enough to peep into their lives but not anarchic enough to experience them on our screens.

According to Paris-based filmmaker Hassane Mezine, it is like an aesthetic of radicality without a radical conscience. And I don’t want to get into this as it becomes repetitive. I deeply respect the people involved in the filmmaking process and the Wakaliwood folks, including Alan Hofmanis, who left his life in New York to make films with Isaac Nabwana. But one cannot help but notice the prominence of the involvement of Global North actors. The description of the documentary implies that it was only after Hofmanis that Wakaliwood broke through into the international cultural consciousness.

Who are you talkin’ to?

Greg Dickinson, a producer of the ACT Human Rights Film Festival, believes that conversation is key to the power of a film festival. The various facets of a festival, such as L&A — imagining the entire event, conjuring a theme, finding a political position, presenting a selection, and experiencing the stylistic treatment of a subject—bring me to the same issue. And that of dialogue.

To my privileged immigrant eye, Finland is a progressive country. There is a will to talk about rights, equality, and justice without fear of persecution. Anna and Pekka agree that L&A has been fortunate to be relatively free from any constraints posed by ideological opponents, collaborators, or sponsors. The festival’s popularity has garnered good ticket sales that enable the festival a reasonable degree of independence in its operations and content. With such fortune that enables a strong political position, I tried to seek out conversations a festival such as L&A might have created.

I can put up a BLM solidarity picture on my Facebook profile or go to a BLM event without having to be racially profiled or heckled by members of white supremacist organisations at the Puhos shopping centre in Itäkeskus. I operate in comfort. Within my comfort zone. But how far does this engagement of mine speak to the daily life and realities of a Black Muslim person in, say, East Helsinki?

Gender and sexuality have been prominent themes in the festival’s films and discussions with the filmmaker. Organisers say they have had similar conversations to address critical issues of race as well as movements such as Black Lives Matter and Me Too. The next thing I naturally seek is the participants in an exchange of views and ideas. L&A defines a conversation as multifaceted and multidimensional. It can be a dialogue of an audience member within oneself or with others about a film or an issue represented in a film. It can be among people in the creative industry about the festival, cinema, films in the festival or approaches to the stylised treatment of a subject.

While I agree with this broad definition of a conversation, I also yearn for something more. Something more discernible. I thought about the idea of a conversation in relation to the African Express in the Finnish context and from the perspective of East Helsinki, which I call home. I thought of the diaspora from various countries in Africa.

Take, for instance, the Somali community. At nearly 24,000, the Somalis are the fifth largest immigrant community in Finland and are very visible. It is also a community that wears multiple identities – being Black, immigrant, or Muslim, as well as the area where they live – which contribute to their racial, political, and cultural experiences in this country.

I can put up a BLM solidarity picture on my Facebook profile or go to a BLM event without having to be racially profiled or heckled by members of white supremacist organisations at the Puhos shopping centre in Itäkeskus. I operate in comfort. Within my comfort zone. But how far does this engagement of mine speak to the daily life and realities of a Black Muslim person in, say, East Helsinki? According to Vishnu, even in a scenario where, for instance, an African is represented in the film and a non-white attendee is physically present in that collective consumption of culture, there is a palpable absence of dialogue. Hence, what emerges is a political engagement that is passive and inconsequential to the lived realities and experiences of the subject. I am reminded of Travis Bickle.

Take it to the community

I met Liibaan Sheekhdoon, a resident of Helsinki and a youth and family support worker for the city, at a bustling Somali restaurant in East Helsinki. They apparently have the best samosas in town. When I told him about this review, Liibaan said he had never heard of the festival. Would he have gone for the films if he had known of it? “I don’t know,” he said. He would have to look at the tickets. “If you take the whole family, it becomes quite expensive,” he adds. Clearly, Liibaan resides in a culture where going to a film usually means a family or community activity.

While prices for L&A are lower than regular cineplexes in the city, they can still be high for someone like Liibaan. Wisam, who further weighs in on the aspect of family, community, diaspora and dialogue, feels there is no authentic conversation. “The films (from Africa) that I go to at a festival may not be of interest to my family or their taste,” she says. “If you take it to the community, they would choose differently.” And in that difference of choice lies the fundamentals of starting a dialogue. Or a missed opportunity in doing so.

The idea of taking it to the community also made more sense to me after I came across Paula, who calls herself an art hustler, at the screening of the Moreno film. She has been attending the festival for as long as she can remember. A story of her experience from another event in 2017 hit home with the idea of generating conversations. “It was in the middle of the war in Syria, and there was a steady stream of refugees to Europe. There was an Omar Souleyman (Syrian musician) concert in 2017, and I heard the organiser handed tickets to Syrians, maybe through refugee centres. There were many independent networks, besides the official ones, giving help to refugees, and the information spread quite organically through those. I was on the front row with a big group of what I believed to be Syrians, thoroughly enjoying the gig. Many of them Facetimed people back home, filming the stage and the crowd, and I think I featured on at least one of those calls with my friend,” she recalls.

This, to Paula, was a remarkable experience. She had seen world music events featuring Souleyman earlier, all organised by a promoter or a festival. However, in none of these she experienced what she did in 2017 – that people from the same community as the artist were thronging the event in an adopted country and connecting two worlds.

“I suppose the main reason is the type of venues and where the concerts are advertised,” she says. L&A does have initiatives to take cinema to a wider audience. For instance, since 2011, the festival has had free Pulpettikino screenings for kindergartens and schools. The annual footfall, according to Anna, is about 5000 children. I wonder if one could take this further and have a series of screenings of films from Africa at the inner courtyards of the Puhos or the Kontula shopping malls. Could we? Please?

I suppose a consultative, participatory, dialogical, and conversational approach for a film festival would require a similar strategy. The question is, can it be done? L&A has the potential and also seems to have the will to make a change.

Hannu Oskala is a musician and former member of the Helsinki City Council. He is also a movie buff. He says, “The question is, what can we offer (for more participation of communities in cultural processes)?” He believes that the festival crowd is still very middle class and that cultural institutions, including festivals, are still in a bubble. There needs to be a push towards getting out of the bubble.

Surveys conducted by the city in 2008 on participation in cultural events in various locations show that places with large immigrant populations scored very low compared with, say, more middle-class White Finnish areas. Hannu feels the percentage is still similar and sees a need to address it. “However,” he cautions, “cultural processes must be tailored. They cannot be imposed.”

I suppose a consultative, participatory, dialogical, and conversational approach for a film festival would require a similar strategy. The question is, can it be done? L&A has the potential and also seems to have the will to make a change. As discussed by scholars of the creative industry, one of the roles of a film festival is to catalyse social change. According to Anna, L&A has been part of the changes Helsinki has witnessed over the past three and a half decades.

Residents like me look forward to a time when the organisation can dismantle power and operational structures within the world of film festivals to make it speak to us. To a point where it can facilitate change in festival culture and make it more meaningful to the city’s various layers of inhabitants and their lives—culturally and politically.

After all, as Bakunin said, isn’t the urge to destroy also creative?