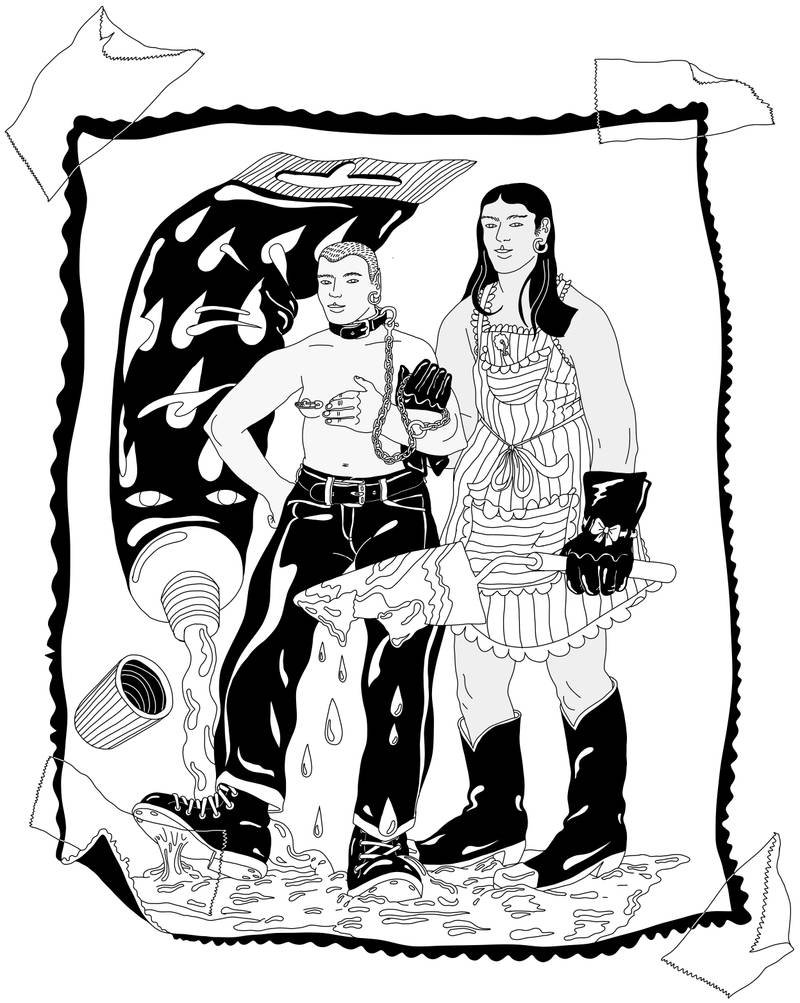

Illustration: Edith Hammar, 2021

Gladys Camilo is a Chicana/Mexican-American painter, dj and textile artist working in Helsinki. She is interested in the intersections of identity and trauma; to dream and explore alternative realities of opacity and agency over her (our) trauma; collective feeling; healing; and the fostering of safer spaces to explore vulnerability and co-care.

What constitutes being a woman or feminine? Why do we have to exist within categories and labels? Maybe we don’t have to. Perhaps gender is just some bullshit we made up.

Loving Women is an exhibition curated by Juha-Heikki Tihinen (in-house curator at Gallery Elverket), featuring works by five artists: Marie Høeg, Ester Helenius, Tove Jansson, Emma Helle, and Edith Hammar. The exhibition explores the theme of love between women, celebrates the decriminalization of homosexuality in Finland in 1971, and tackles the gender gap between lesbian and gay representations in publications and art exhibitions. According to Tihinen, art exploring lesbian love is often overlooked compared to art exploring gay love within art institutions. In addition, the exhibition attempts to bridge historical and current representations of womanhood, femininity, and their spectrums. As Juha-Heikki mentions in his extract of the exhibition, "The images and works presented here demonstrate how broad the scope of femininity is, and how its various representations escape definition while also creating new realities.” 1

Tihinen says that the exhibition attempts to diverge from classifications and definitions of gender identities, as art exists beyond such structures. However, gender binary norms often dictate how we present ourselves: feminine and masculine; gender and sex are considered stable and never fluid. Gender is a social construct that we perform daily, reinforcing labels and categories which invisibilizes other genders and sexualities.

So if you are already categorising and comparing based on gender, aren’t you already putting them in a box?

As some of us know, established spaces like Gallery Elverket often struggle to move past categorising artists and art: queer art; gay and lesbian art; queer Black art; art by queer women; and art by queer women of colour. These performative identities reinforce social constructs, which violate such identities and genders. As Isabel Hufschmidt bluntly lays it out in her essay, “The Queer Institutional, Or How to Inspire Queer Curating,”

“The art scene is insistent that it’s completely free and open—because we, who work with art, cannot by definition be reactionary. But for those of us who work in museums, or the institutional side of the art scene in general, there is a nasty surprise: the selection process in the arts constitutes one of the most hyper-Darwinistic competitions in any cultural reality. Infrastructure, values and contexts, display, critique, and discourse are carefully layered, checked, and categorised.” 2

For the structure of this review, I wish to walk you through each room of the exhibition (a total of five rooms) as a way to share my first-hand experience; allow space for observation and reflection about each artist and their artworks, and analyse the exhibition’s presented “progression” of gender identities from the 19th century to today. While I talk about female bodies and forms, women, and womanhood, I recognise that not all bodies that look like this belong to women, and I honour the idea that they could be non-binary or other identities.

Room I

Emma Helle, Kvinnor och kärlek (Women and Love), photo: Ahmed Alalousi

I immediately notice the juxtaposition of the old and the new co-existing in one space, in dialogue with one another: works by Tove Jansson, Ester Helenius, and Emma Helle. Ester’s androgynous red-winged angel, Playing Angel, and her floral still life, Esters in a Vase, tie in traditional notions of femininity: passive, soft, calm, and pretty. When observing Tove’s painting, Before the Masquerade, similar ideas come to mind. Emma’s fluid and textured sculptures, Baba Jaga and Marie Antoinette at Night, explore the female body and identity through materiality, disrupting the passive and the soft. All of the works explore the meaning of womanhood within their context.

As I look around the room, I visualise the various forms in which the white female body has been historically expressed within western art: graceful bodies barely covering their bits with flowy garments, ravishing floral arrangements resembling a woman’s genitalia, curves, sex appeal, and submissiveness with a touch of violence—the exploitation of womanhood through contouring the female body in the arms of another being or landscape.

How does the exhibition shift away from the recurring violent categorization of gender representations, identities, and sexualities?

Room II

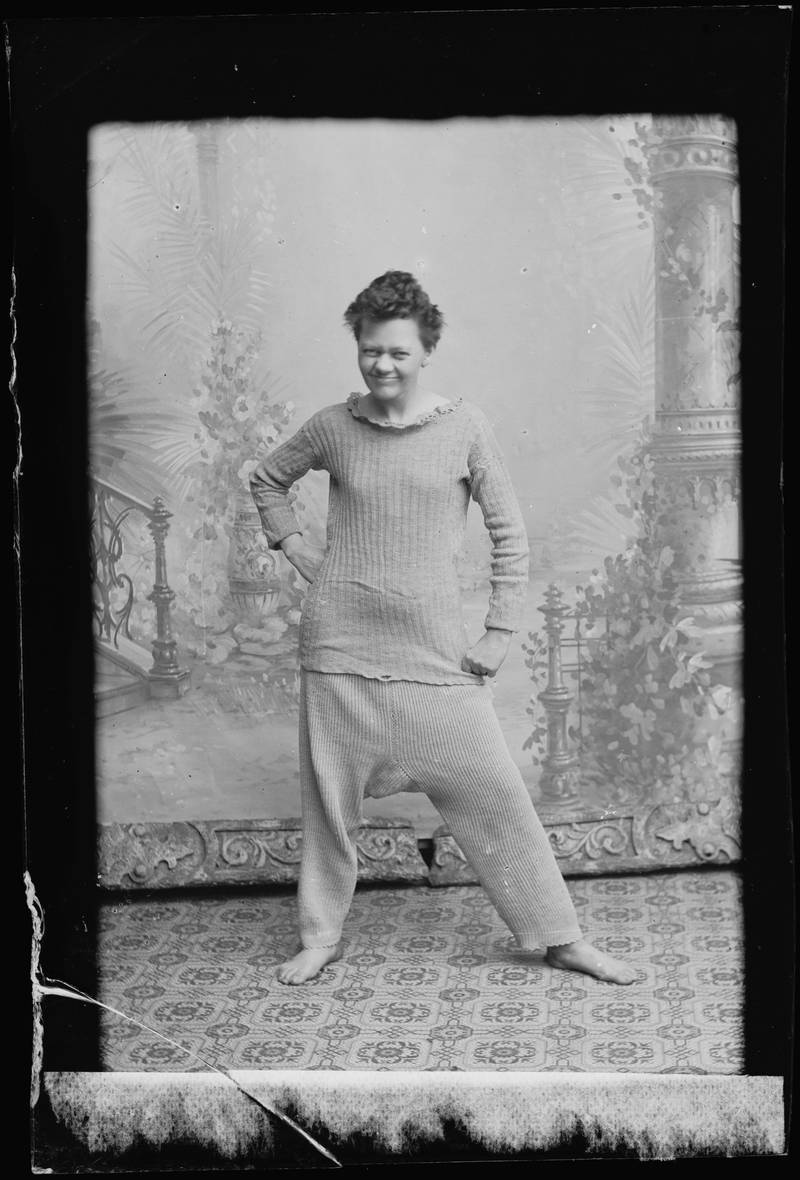

Marie Høeg, photography 1895 - 1903, Preus Museum, Norway

The walls in the second room display works by Tove, Marie, and Ester. Various sculptures by Emma are arranged on a table on the right side of the room, and the larger sculpture, Sottobosco, sits on a tall podium next to the window. I notice the contrast between the rough textures and the graceful and fluid movement of the bodies as I examine the sculptures more closely.

The bodies in Emma’s sculptures feel free, safe, and unobserved by the male gaze; the figures embody fluidity. I am reminded of Petra Van Brabandt and her research on wet aesthetics, which explores how the body experiences wetness in relation to art, and the stimulations entangled with experiencing such works. It is about fluidity: movements of the body, paint (in this case, glaze) and flesh linking us to what we are and where we come from (fluids and compost), how skin and hands react to the desire of touch and possession.3 When I encounter the works by Emma (and later on, those of Edith), I openly embrace the bodily sensations and reactions that come to me through this interaction, experiencing the ever-present wetness and fluidity of their works.

Marie’s photographs, made between 1895 and 1903, are images of playful bodies wearing what they want. I felt admiration towards them for defying such gender roles and representations in their time. The energy captured in the photographs reminds me of a brazen childhood—cartwheels; jumping; stomping and screaming; dressing up and dressing down. On the other side of the room, there are images of people emulating traditional male roles of the time—smoking cigars, drinking, and playing a game of poker.

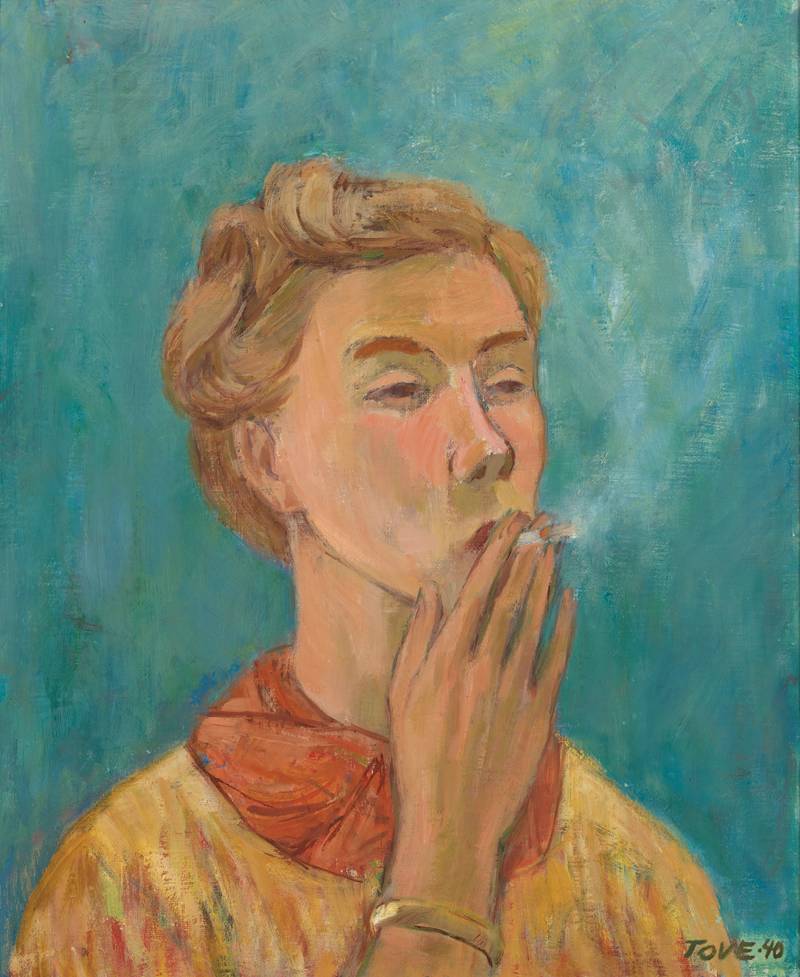

Paintings by Ester put forward softer representations of feminity: L’initiation’s spiritual overtones depict androgynous beings amid an initiation, while Flowers in a Vase is a colourful still life. In dialogue with these are more Tove paintings—two self-portraits and a portrait of a woman, Girl in fur—that bring forth the unapologetically candid energy of being oneself. One, which caught my attention, is a self-portrait of Tove titled, Smoking girl. Tove stands with a contemplative posture and a hazy look as she takes a large drag on her cigarette, not giving a damn. I saw something familiar there that made me chuckle.

I saw my friends

I notice the left side of the room feels cramped. It is challenging to take a step back to look at the works on the walls. As I enter the third room, I reflect on how imbalanced the second room felt—the noticeable juxtaposition in the first room is lost. Traditional representations of gender and classic notions of femininity and womanhood are taking over once more.

Where is the acceptance of a true queer revolution? Where is the disruption? Where is what I’ve yet to see in these institutions and spaces?

Were these artists/artworks presented in the exhibition because gender identities and representations were/are central themes in their visual works? Or because they were/are queer artists, we must therefore interpret their works only through a queer lens? Is that what these artists desire? Is that the case in these works? There’s no deep exploration of queerness within contemporary Nordic art and art history. This exhibition seems to stick to outdated ways of looking at gender, for queerness can exist beyond just sexuality. It can function as an aesthetic and a tool to rethink society and heteronormativity and other ways. “Queer is well beyond mere biology.” 4

Room III

The video installation presented in this room shows, Travelling with Tove (dir. by Kanerva Cederstöm), comprising documentary footage of the artist’s travels through Japan, Mexico, Hawaii, and the United States with her partner Tuulikki Puetilä—a humorous and insightful film about Tove Jansson.

To the left side of the room is a large mural by Edith Hammar. Edith’s graphic works are painted onto the wall, filling the space from floor to ceiling. I admire the beautiful non-conforming bodies that defy everything else present in the exhibition. Their mural adds something refreshing to the exhibition, something that’s been missing. Across the video installation is a row of photographs by Marie Høeg, a continuation of gender expression and identity, understood as cross-dressing at that time. I catch myself smiling every time I make eye contact with these photographs. There is a genuine expression of joy captured in those images that continue to pull at me repeatedly. To the right, Coriolis, a large sculpture by Emma, sits on a pedestal—a mound of fleshy lumps and balls. In contrast, a female figure seated at the top with her legs split wide open, reclaiming her body, sexuality, and pleasure. Emma’s works live in the realm between empowerment and whimsy.

Tove and Ester’s visual works feel static and out of place compared to the previous works. Tove’s charcoal drawing, Self-portrait, slips my mind—and attention—along with Tove’s The Girl and the Cabinet and Ester’s Naked Woman in Front of the Mirror. These works feel like unnecessary additions to the room as it reverberates what has been stated before.

Just because it’s Tove, is it necessary to have her in every room?

More traditional representations of femininity and gender continue to fill the walls, with no progression or growth in sight. The further I go, the further I question the context of the exhibition, as I have yet to encounter more works which break away from binary categorisations of gender and sexuality. The content and the context of the exhibition feel disconnected.

At this point, I am slightly over it.

Room IV

Tove Jansson, Smoking Girl, 1940, ©Tove Jansson

There is an audio work here, a recording of Tove Jansson reading one of her short stories, The Great Journey, from the collection “Dockskåpet.” I moved closer and placed the headphones on my head. However, I soon realised that I couldn’t understand the Swedish audio. There wasn’t a translation of the reading in English or Finnish, only a brief description in the room sheet. I put down the headphones, disappointed that I have missed out on the aural component of the exhibition. This begs the question, who is the exhibition for and who had access to it?

Finnish-Swedish community? Not for me, that’s for sure…They made that very clear.

A painting of a reclining nude by Tove, titled The Model, sits across the room from the audio work. The figure is curled up on a messy bed. I think about the body language that we are used to seeing in these paintings: the classic white reclining nude in western art history—exposed and open bodies, aroused and in ecstasy, objectified and violated. But in this case, it feels like an intimate moment was captured in Tove’s context, a genuine representation of a body at rest. To the right, works by Emma and Ester are placed in dialogue with Tove’s nude. Emma’s reclining nude, Ondine, is fluid—bodily and material movements, drips of glaze flowing down the body and dripping off genitalia: raw and empowering. In contrast, Ester’s reclining nudes, A night and a Dream, are softer, almost like a whisper. They rest along a riverbank as they wash themselves. All three artists study the same subject—the representation of the bodily form—yet, their contexts are different as they explore traditional and contemporary representations of femininity.

Room V

The final room is a hallway with a ramp that leads back to the main hall of the gallery space.

Edith’s largest work is displayed here, a second mural. A queer utopia: a community embrace, a safe space for self, kink, and sexual exploration. It’s the kind of work that I want to see take over. As I walk back to make a deeper observation, I notice something new: a doormat with a text that reads “welcome” and a couple embracing each other to the left of the doormat. There’s a sudden tug in my chest, a flashing moment when the body reacts before the brain can register the meaning—and then it clicks—I’m filled with self-acceptance and teary eyes. Being in dialogue with this mural made me feel as if I am also being welcomed into this paradise and community of love, acceptance, and freedom. I feel fuzzy inside as I look forward to such realities manifesting today.

That’s it?? Where is the progression of various identities? From what I can see, it’s just the exploration of femininity, the female body, and, once in a while, the exploration of masculinity. Is Edith Hammar carrying the weight of representing everything queer and contemporary?

“Alas, exhibitions that seek to explore queerness collapse too readily into merely explorations of sexual differences, leaving the whole apparatus of queer—its defining refusal to accept dominant culture’s denomination of a single majority and minority sexuality—unspoken.” 5

</3 </3 </3 </3

As I complete the full circle, I try to re-organise my thoughts and emotions. I come to terms with the fact that I’m unsatisfied, leaving with the desire for more contemporary takes on womanhood and other gender representations. I’m irritated by the prevailing imbalance of each room within the gallery space. In the end, I read the exhibition as a historical exhibition and not something “from the 19th century to today,” as stated in the curatorial text. The exhibition skirts around gender representation and love between women (or people) but never fully arrives or acknowledges its progression. I even feel anger, perhaps because the exhibition merely conforms to norms. It makes queer art and its topics palatable, unchallenging, and easier to digest for the typical crowd of such institutions – perpetually cycling Tove Jansson through art institutions as a “crowd-pleaser” and instrumentalising Edith Hammar’s works under the guise of gender diversity. It’s an institution checking boxes with minimal attempts to include other contexts, not daring to transcend anything beyond white, thin, and canonically beautiful women loving women. Using Edith’s work in the poster further misleads the audience about the actual content of the exhibition.

The title, Loving Women, thus, is reminiscent of clickbait.

I am in no way dismissing the efforts of the artists and the beauty and intrigue of their artworks. The artists and their works are fantastic. However, the context in which the works were displayed was problematic for me, such as the labelling of gender, the unbalanced and narrow focus on genders and sexualities, and the curatorial language used to exclude the non-binary bodies in the exhibition. The exhibition could have benefitted from the curator broadening the scope to include more works exploring diverse bodies in love beyond the labels and confines of gender and femininity. Do such exhibitions choose not to include other genders, as it would be too complex and difficult to explain these lived experiences and identities to their crowds? And, what about power structures and safety within the curatorial practices when working with underrepresented* artists? Who was prioritised? Who gets to speak, and on whose behalf? Whose needs were taken into consideration, and whose desires? Who felt safe, and who didn’t? Who felt understood and seen, and who didn’t? What happens to the artist’s autonomy over their own identity and artistic practice when taken under curatorial work within established institutions? The knowledge concerning diversity, language, representation, and inclusivity is severely lacking in this institution.

Battling to make sense of it all, I think about the future of queerness within art institutions, queer art, and queer curating. Queerness is radical, inclusive, intersectional, and progressive, which felt missing in the exhibition. We need more of this, but how do we get there? How can queer curating exist and change what art institutions look like?