Taina Rajanti is a (retired) researcher, university teacher and intellectual activist whose academic background is in social sciences, but who has throughout her career engaged in trans-disciplinary projects and extra-academic activities. She is especially interested in issues of space and place.

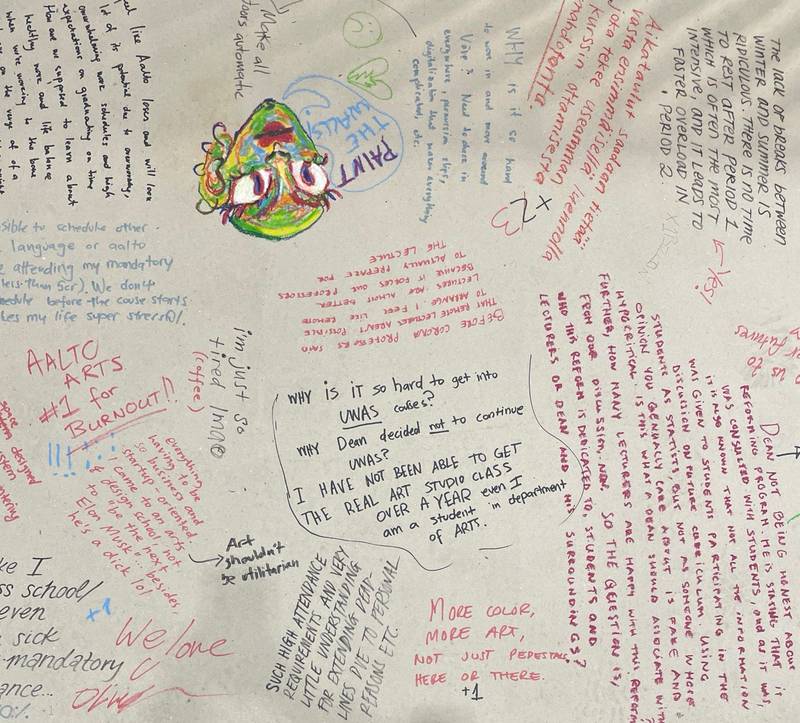

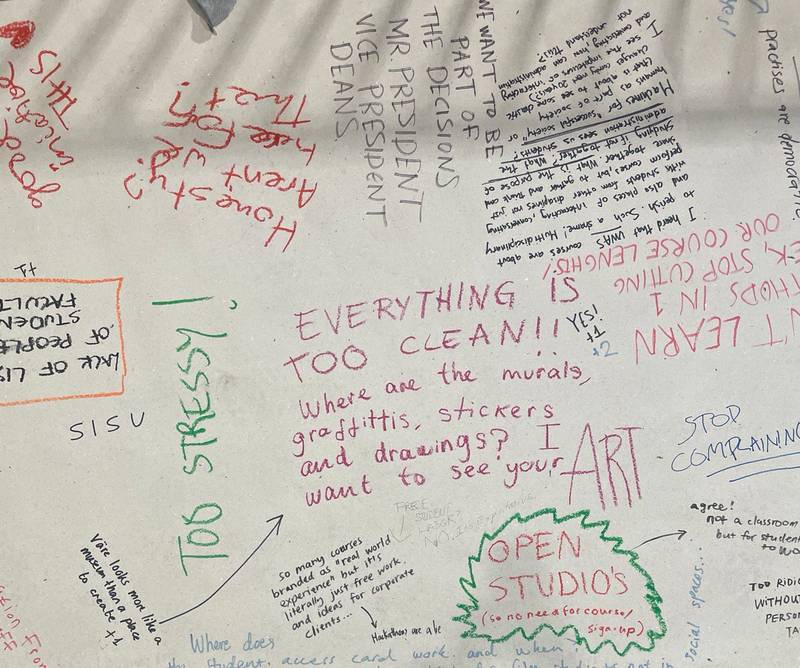

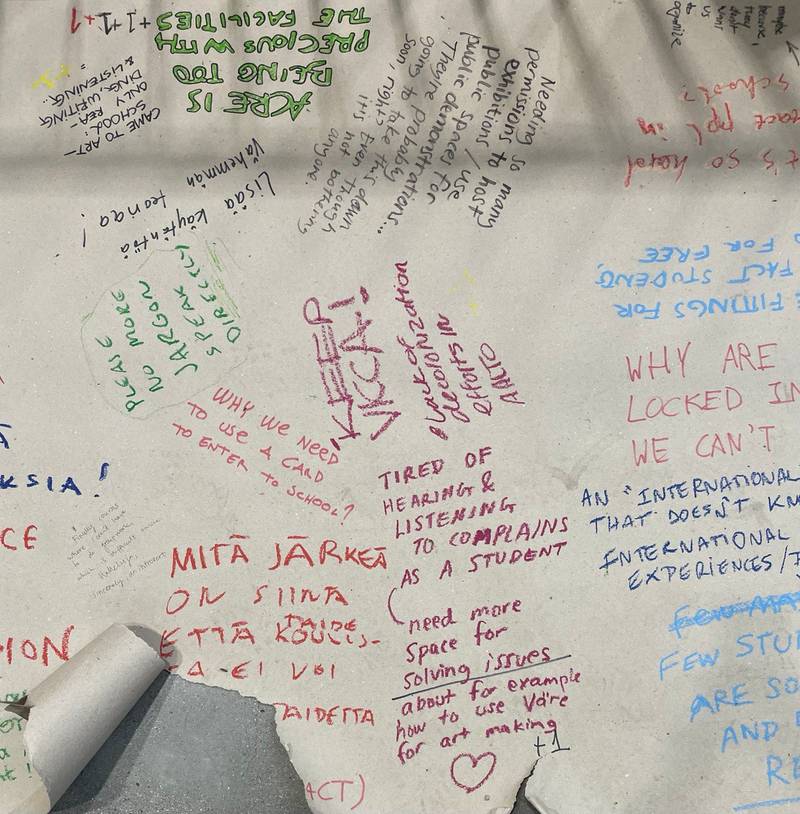

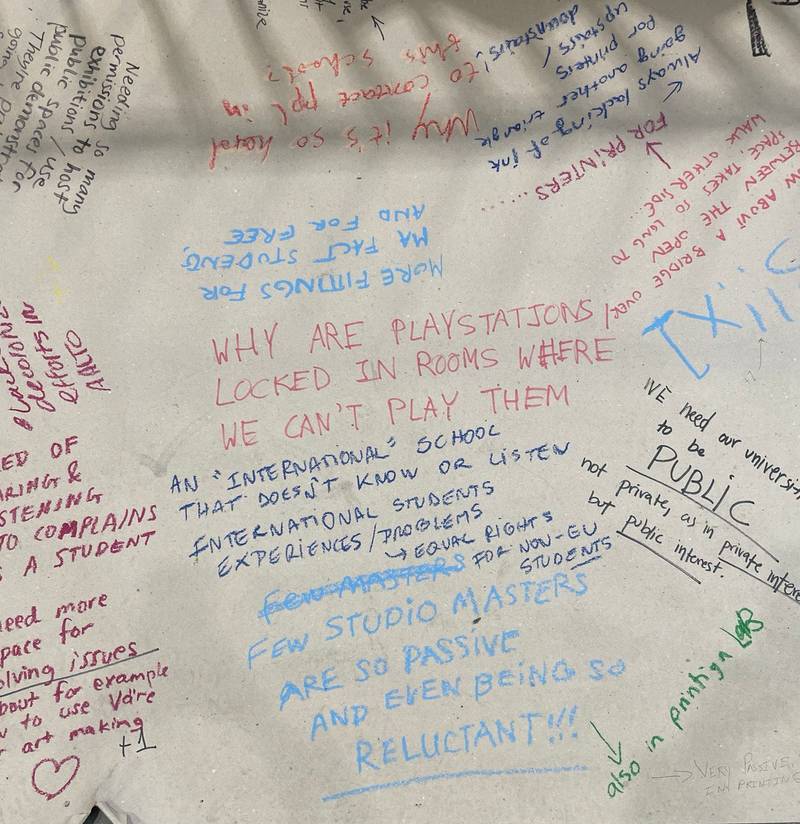

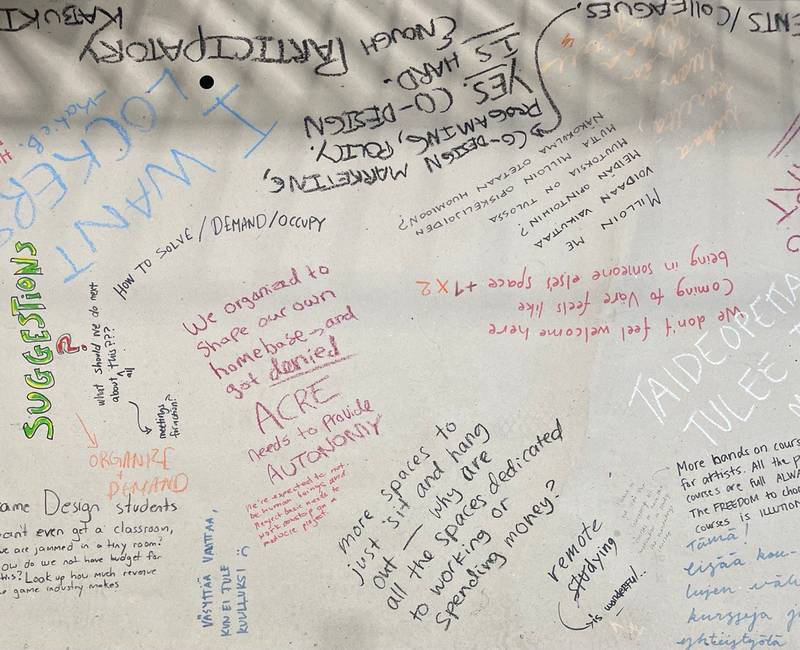

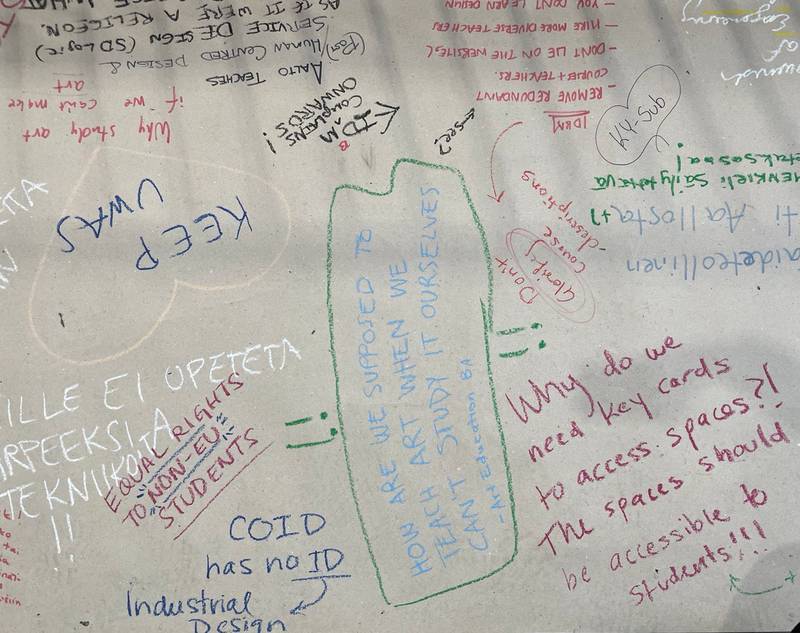

One is reminded of the famous ghost of the Communist Manifesto: students in the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture have taken to occupy the ARTS building Väre, organising demonstrations and negotiations with the university representatives. Not bad!

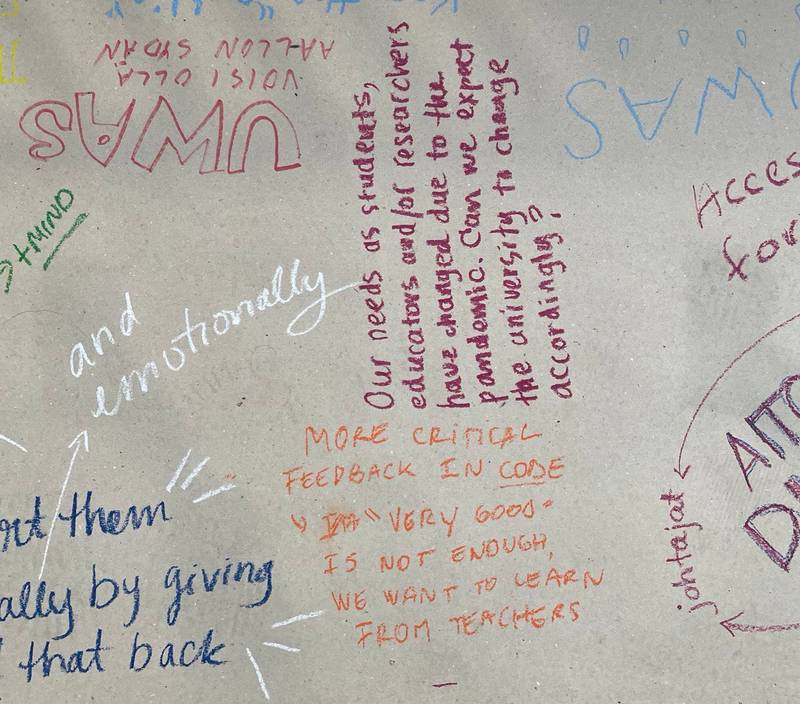

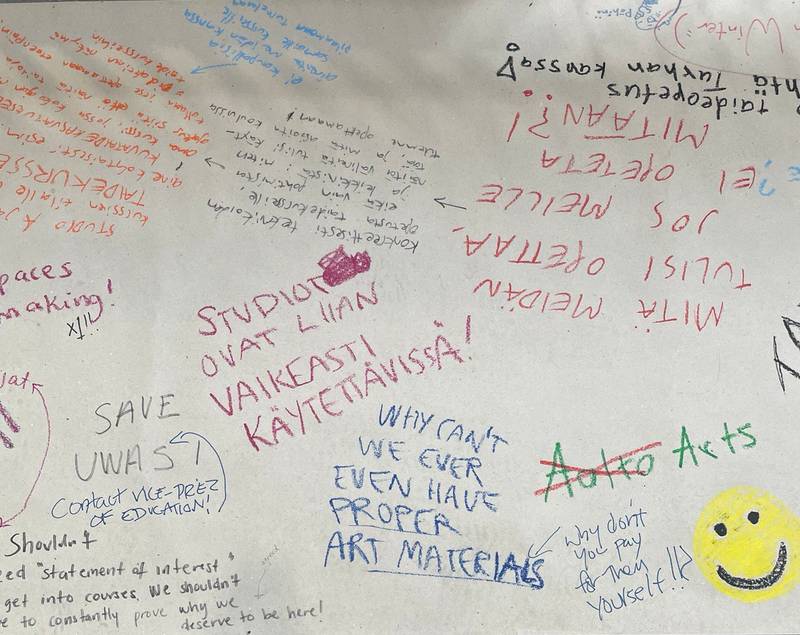

What has angered students are the recent cuts and reorganisations of the departments and programs (getting rid of some famed and popular ones like UWAS) and the inaccessibility of the Väre premises for student use. The university argues that the teaching of art is not “efficient” – too many alternative courses with too few students. And that since budgets have been cut – and are going to be cut – there have to be ‘less’ courses with ‘more’ students.

Weighing everything – education, art, well-being, enjoyment – against resources invested and goods produced makes sense within the logic of neoliberalism. But neoliberalism is an ideology. The university’s argument of a scarcity of funds and the necessity of cuts is just the hand pointing to a comfortable spot. Look at the hand, not where it points!

In arts higher education, alternative courses have been abundant – some also invite specialists to give lectures, workshops, or whole courses. Most of the abundance has been provided by teachers already employed by the university. I’ve, e.g. taught a few UWAS courses myself, and most people I know who have done those have been part of the ARTS faculty. Thus not an extra expense for the university at all. Therefore I find the university argument to be a bit off-key. I don’t think the issue is the scarcity of funding and the need to reduce courses, visiting teachers, programs, and resources. This is just the form of an excuse since it makes the policies and decisions undeniable, objective, lamentable, but necessary – not a choice of the university, nothing to do with arts.

Weighing everything – education, art, well-being, enjoyment – against resources invested and goods produced makes sense within the logic of neoliberalism. But neoliberalism is an ideology. The university’s argument of a scarcity of funds and the necessity of cuts is just the hand pointing to a comfortable spot. Look at the hand, not where it points! The hard gripping system has been termed “cognitive capitalism” (see Yann Moulier Boutang) or knowledge capitalism, “which is founded on the accumulation of immaterial capital, the dissemination of knowledge, and the driving role of the knowledge economy”. This means it is not just about turning education, art, well-being etc., into commodities and weighing their value accordingly, but the economy relies on these immaterial goods; and, thus, on controlling the forces of production that create the intellectual, creative labour. The burning issue that cognitive capitalism as a system and its institutions likewise are confronted with is, as Foucault said: “how to control the many as many”, “how to control a force that needs to be free to be productive?” This is where the budget cuts and reorganisations, and just as importantly, precarisation and hierarchisation, come in.

When Aalto University was founded by fusing the University of Technology, the School of Economics, and the University of Art and Design, art was pronounced as a fundamental and valuable element of Aalto University. In Aalto’s strategy, art was proclaimed as basic research, something without which no practical applications can be achieved. But the demands to reorganise and cut down departments and programs and practices in ARTS started immediately, definitely with a focus on programs of art. Let’s look at ViCCA, the MA in Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art.

The program was international from the beginning, and our students came from diverse backgrounds, also professionally. Initially, there was no tuition fee for non-EU students, and we felt that the decision to install such a fee was unjust and harmful. The decision was made by and during a right-wing government.

We had an MA in Visual Culture in the Pori department/unit. We foresaw and were all the time very aware of this demand, especially programs of art to continually justify their existence and cut out elements considered extraneous by executive decision makers, and tried our best to forestall harmful cuts or reorganisations. Thus, in 2012 we sat down with people from the Fine Arts and Environmental Arts programs and the minor in curating (CuMMA) and created ViCCA (Visual Culture and Contemporary Art), which started in 2014. ViCCA was explicitly planned to fully exploit the potential of a new university where “art meets science and technology”, as the Aalto website banner states. We wanted a program that looked at connections and uses of art for various other disciplines, which opened new possibilities for people coming from within arts. The first version had two “majors”, ViCCA and CuMMA, which we later merged to sc. ViCCA 2.0 or Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art, as we wanted the curating to be better integrated and accessible to anyone interested.

The program was international from the beginning, and our students came from diverse backgrounds, also professionally. Initially, there was no tuition fee for non-EU students, and we felt that the decision to install such a fee was unjust and harmful. The decision was made by and during a right-wing government. It felt to be just the first stage, extended to all university studies, and made higher education accessible to only students from wealthy families. As we went on with the program, our courses began to attract students also from other programs. Our students were enthusiastic, motivated, active people, and I’ve learned as much as I’ve taught. Our students would participate in experimental exhibitions and events and organise such events – as part of their studies and beyond. Our students have formed the basis of many artists and cultural collectives like the Museum of Impossible Forms, Third Space, Pixelache, Globe Art Point, Feminist Culture House, Porin kulttuurisäätö and have curated collectives and initiatives - like the Academy of Moving People and Images, and have founded indeed this very publication NO NIIN, to mention but a few. Our students/alumni have received awards like the Sarjakuva (comic) Finlandia (at least twice now). They’ve done outstanding projects and MA theses, some of which have been published as books.

Oh yes, “we” and “our”. Already during the Pori years, my colleagues Pia Euro, Max Ryynänen and I wrote the article “Teaching as a Work of Art”, where we analysed what we termed the “Pori school of Pedagogy” based on the predecessor of ViCCA, MA in Visual Culture.

ViCCA was built on precisely these same pedagogical principles:

- Motivated and committed teaching community,

- Intellectual democracy and openness of communication,

- The staff concentrating on their fundamental task: art, study, teaching and research.

- And very importantly: “Intellectual democracy, outsiderish daring, and concentration on the fundamental task cannot flourish if one focuses on gathering points and credits and fighting with colleagues for diminishing resources and posts.”

As I have seen and see it, Aalto (ARTS) has plodded on through its existence to outdo precisely all prerequisites these principles are grounded on, thus getting rid of those teaching communities – starting with pushing the attention of teaching faculty to gather points and credits and competing with colleagues for diminishing resources and posts. Precarisation of academic positions has been a constant practice in Aalto – instituting the fixed term as the norm for most positions and shortening those terms, making recruitment even more rigid and evolved (and expensive), taking recruitment decisions out of reach of those communities they regarded, requiring faculty to keep proving they’re competing for the position they hold not by doing the job but by “gathering points and credits” so that many discover that they become incompetent in their jobs while doing it. And, so that precarisation and constant change of teaching staff would cause the least trouble, the university sustains standardised curriculums and content that anybody can teach anybody with reasonable basic competence. Precarisation demands that the content is fixed and that the people are interchangeable. And that people don’t form too committed communities.

The Väre building, which started by materially dissolving all previous communities created around disciplines and programs, is a neat finishing touch to this control policy. To have a building that should host making, studying, researching, and exhibiting arts but lacks spaces for making, studying, researching, and exhibiting them.

Aalto ARTS has also been disbanding all bodies, communities and practices of intellectual democracy. All those councils and boards that did the planning and decision making on the varied levels – programs/units/faculties/university – were disbanded. There had been bodies like department boards, or the school-wide “teaching council” that had a representative from every program and discussed and made policy decisions, or a school-wide council for doctoral studies that decided on the intake of students. Nominally “power” to make decisions was handed to heads – program heads, department heads, deans etc. – but all decisions, all allocation of funds and resources, and all demands for restructuring and development have been handed down the chain of command from the top, step by step, and have arrived as commands and demands. Faculty and staff have gathered in meetings and palavers. Still, those have been the forums to hand down the orders, not for open discussion leading to democratic decision-making. There may be cute couches, colourful mugs, and hip coffee machines for students and faculty, but all important decisions have disappeared to the executive level.

The Väre building, which started by materially dissolving all previous communities created around disciplines and programs, is a neat finishing touch to this control policy. To have a building that should host making, studying, researching, and exhibiting arts but lacks spaces for making, studying, researching, and exhibiting them. The school finally took some measures because of significant and voiced dissatisfaction, but the building remains a hostile environment for its users. Ironically, the metro station and the supermarkets and cafes make for a much more welcoming atmosphere, where many people take their studies and meetings.

Money may be something the university establishment is even ready to discuss and negotiate – money is a quantifiable, concrete resource, and negotiating it will not necessarily touch and question power structures and practices. It would be nice if instances like units and programs were able to decide how to deal with cuts of funding, e.g. how to find economical studio spaces or take teaching out of the academy and how to juggle with inviting visitors to keep the curriculum updated. Though Aalto has been adamant that teachers and students should use only Aalto spaces, reluctant to allow programs like ViCCA to find alternative solutions outside Aalto premises. And even more adamant about keeping to its structures and practices of power – control by precarisation and hierarchisation.

I cannot but think that the constant cuts and reorganisations of the teaching of art are because what art is is not something that can be standardised and defined once and for all but keeps changing and evolving. Consequently, it does matter who is teaching and studying because the definitions will shift accordingly.

But why has art explicitly been targeted for cuts and reorganisations? Why would a program like ViCCA, which appears exemplary in the Aalto context as to content and outcomes, constantly suffer cuts and finally be ordered to be transformed into a major, not a program of its own? (This transformation does not concern ViCCA alone, but I see it as one of the many demands for constant reorganisations ViCCA has had to struggle with.) Not because it is too expensive. As I said previously, the abundance of choices and courses has been the work of people anyway employed by the university. It has not required excessive extra funding. Our courses have always had the maximum amount of students, and the funding needed per person has not been unreasonable. And as the courses attract students from other programs, our teaching has benefited more than just the ViCCA students. ViCCA teaching has involved a multiplicity of collaborations with partners from other universities and institutions, also internationally, and with societal actors and institutions, furthering the societal impact of Aalto University. All because the teachers and the students are actively interested in what they do in society and the world.

I cannot but think that the constant cuts and reorganisations of the teaching of art are because what art is is not something that can be standardised and defined once and for all but keeps changing and evolving. Consequently, it does matter who is teaching and studying because the definitions will shift accordingly. What art is and how it should be taught is too damn hard to control. Especially from the top down by people who have no idea what it is about and whose policy is not to listen to those who do.

Of course, intellectual democracy and motivated communities were never a natural characteristic of any university. They were the result of years of struggle. Universities are, after all, elite institutions and have always served the goal of producing specific kinds of labour and thus being permeated by the needs of the ruling classes. Therefore, I am glad to see that students have felt the necessity to demonstrate and make demands. Not out of ghostly nostalgia, but because that is the only way to achieve anything. Democracy, intellectual or organisational, can never be a solidly achieved and established thing—it is something you do and struggle for. It’s a mess, like the best things in life.