Image by Danilo Correale

Elena Mazzi (1984) is a visual artist, working with specific geographical and socio-political contexts. She studied History of Art (Siena), Visual Arts (IUAV, Venice) and Fine Arts (Royal Institute of Art, Stockholm). She is currently a PhD candidate at Villa Arson and Université Côte d’Azur, Nice. Her works have been displayed in many solo and collective exhibitions all over the world.

Annalisa Pellino has a PhD in Visual and Media Studies and currently collaborates as assistant professor and research fellow with the Department of Communication, Arts and Media at the IULM University in Milan (Italy). Her research interests lie in the field of sound and voice studies, audiovisual culture and contemporary art practice, film circulation and exhibition, media archeology and videographic criticism.

Art Workers Italia (henceforth in the text AWI) is an autonomous and non-partisan association founded in 2020 in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic from the political imagination of a group of art workers, with the aim of giving voice to the many Italian professionals who live and work in beyond-precarious conditions. Moving from the assumption that the entire contemporary art system of the country needs to be reformed and made more inclusive and sustainable by contrasting all forms of exploitation, AWI has always aimed to be a landmark not only for art workers but also for non-profit organisations, for public and private institutions, and even for policymakers. That’s the reason why, since its foundation, it has collaborated with art and cultural institutions, research institutes and universities, lawyers and experts on public administration and fiscal policy to provide art workers with practical and theoretical tools that are useful in their daily routine and for criticising the exploitation of their labor.

AWI, Il lavoro dei sogni / Il sogno del lavoro, Piccolo Teatro Aperto, Milan, April 30, 2021| Photo courtesy of Gilda Panizza

Not an Artwork but Art Work

Despite its young age, the association has had to constantly re-modulate its approach in line with several changes, both internal and external, that have occurred over the last three years. A short historical digression could help to elucidate this.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, namely, the first and second lockdowns, which were particularly strict in Italy and brought into even sharper relief the many contradictions and disparities the art world thrives on, many people enthusiastically joined AWI, thousands of them signed our Manifesto, and hundreds took part in the assemblies and the weekly meetings. So many people joined that we decided to articulate our activities around different topics, round-table discussions and working groups: one devoted to the investigation of the history of cultural workers in Italy, one on the same aspect abroad, one to legal and fiscal issues, and so on, along with an editorial and communication team, just to name a few.

At that time, the interest in what many consider to be the first art union in Italy (even though formally we are not) was high, also due to the fact that many art workers were excluded from the distribution of emergency funds, inasmuch as they were not considered recipients of the social shock absorbers that the government allocated to other types of workers (especially when employed in the public sector or easily identifiable by the tax authorities).

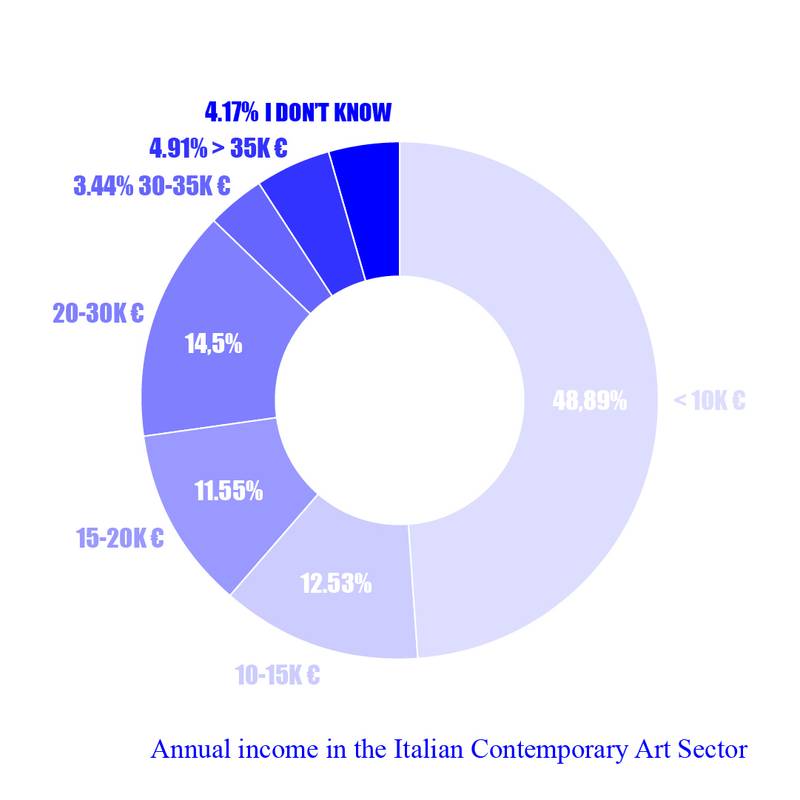

Why? The reason is as simple as it is disarming. According to a survey on the conditions of art workers in Italy, we carried out in 2021,1 36.6% of them resort to undeclared work, the so-called “black work”, as a secondary mode because they have an income of less than 10,000 euros per year, which is, according to ISTAT (the National Statistical Office), below the poverty line. There are too many people (mostly women) underpaid and with no welfare State protection, and the flipside of this is that 85.9% of them had obtained either a master’s or a higher education degree or achieved a very high professional level. We are not speaking of persons in their early twenties but those in their thirties and forties. Worryingly, our survey also revealed that 79% of art workers do several jobs in contemporary art and other fields of work because their supposed principal income is not enough to support themselves. Yet, 58.5% of them work more than 40 hours per week, and in some cases, over 60 hours, even if the Italian law states that the standard working time should not exceed 40 hours per week. Finally, and most notably, there are no regular contracts for 55% of these jobs.

AWI, in collaboration with ACTA (association of freelancers in Italy), Italian Art Workers - a survey. May 2021

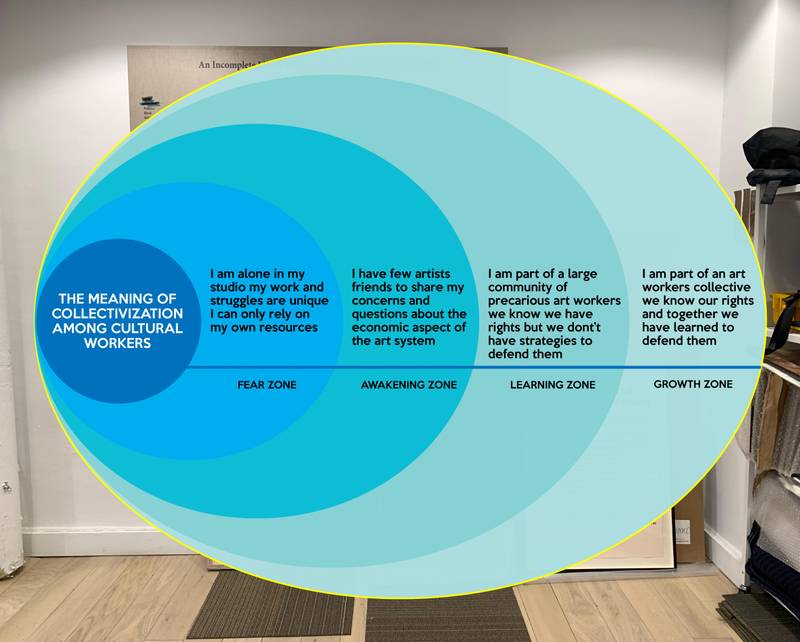

But there’s also a deeper sociological reason behind such an alarming scenario; generally speaking, cultural work in Italian society is not deemed as a real job but something that is done for passion or to gain special social status, that is, to enter a world where identification, approval and social recognition are regulated by elitist logic and standards. Even if this situation has not changed significantly since the end of the pandemic, many who were actively involved in AWI returned to their own projects in search of grants or funds, often continuing to accept underpaid jobs, precarious positions and unfair employment conditions. This gives a more exhaustive picture of the Italian context; indeed, if, on the one hand, there is a total lack of rules and government measures to protect cultural work, on the other, many art workers themselves do not have the critical thinking attitude to analyze their own conditions and to claim their rights. The rise of neoliberal logic does not help this lack of political awareness, inasmuch as it fosters competition rather than solidarity and makes people more isolated and vulnerable.

Nowadays, AWI can count on the active participation of about ten people and a few hundred members. Our main efforts are devoted to spreading awareness on these issues via lectures and workshops in universities and academies, often invited by curators, artists or scholars who teach there and who point out the lack of courses aimed at educating students not only on how to become an artist, a curator, an archivist, an art writer and so on but also on how to do it professionally, that is, how to be recognised by the world as a professional.

In 2021, for instance, we were invited by Fondazione Mondinsieme, within the European project PALKonnect, to develop a toolkit for art workers with the aim of fostering “Empowerment of Social Inclusion Groups through Creativity and Cultural Works”. On that occasion, we organized four lessons on models and useful practices for fair remuneration and legal protection and provided a checklist for art workers and institutions by gathering together all the information and research we previously did. To obtain and know how to use legal protection tools has always been one of our main goals. That’s the reason why we developed contract templates that are useful in different situations: from selling artwork and protecting one’s own authorship to agreeing on fair work conditions with the commissioners.

This also gives an idea of what a collective effort can do; the preparation of one of these contracts requires months of work and can cost thousands of euros, but our members can use it for free, thanks to the expertise and collaboration of the art lawyer and professor of Comparative and Art law, Alessandra Donati, who has always supported AWI. This tool has been designed to be used together with a Guide to recommended minimum fees, which includes: a checklist of good practices with some tips on how to ask for a fair fee and set up a healthy relationship with the client/commissioner, and a list of different job typologies with the corresponding minimum fee – which took inspiration from similar tariff-based systems already used in other countries, for instance in the Netherlands (Kunstenaar Honorarium), Belgium (Juist is Juist), Switzerland (Guidelines of Visarte), in the UK (a-n/AIR Paying Artists Guide), USA (W.A.G.E.) and in South America, between Argentina and Chile (Trabajadores de Arte Contemporáneo).

AWI, 2020

Well, we know where we’re goin’

We would like to extend this discourse to the whole sector by producing a proper Code of Ethics for Cultural Institutions, both public and private. However, our main goal is to be included in a series of measures that the Italian parliament is currently discussing to support cultural work. The reorganization of the legislation on work in the artistic and creative field is actually underway, and they are focusing on the possibility of extending the worker categories that can join the social security and pension fund, along with a new law that guarantees the continuation of pay in cases of intermittent income, which is typical of art professions.

To understand how this achievement is as important as it is difficult, it is worth mentioning that “the issue of social guarantees of artists is not fully solved in Italy, although it has been attempted to solve this problem since 1930”.2 Furthermore, only recently, in 2021, Italy considered adopting the European Parliament resolution on the social status of artist (2007),3 with almost 15 years of delay, but so far, it has not undertaken concrete actions of social guarantees, such as sickness insurance, unemployment insurance and pensions. The situation is so serious that, still in 2021, ICOM Italy expressed its:

strong concern about the spread of underpaid or unpaid work in museums and called on public administrations and all employers to recognise the specific professional skills and to pay compensation appropriate to the functions required, in line with our Constitution, to protect the human dignity of workers (our translation).4

It goes without saying that social justice and fair working conditions are not a priority in the current political agenda. Just think that, to make matters worse, as we are writing these lines, the far-right government led by Giorgia Meloni opposed the minimum wage for all types of workers, just to give an account of the long road we still have ahead.

Art Workers Italia Beyond Italy

Given this, one could consider the activist commitment of AWI as a site-oriented practice, which, according to Miwon Kwon, is enhanced by the increasing nomadism of artists, an idea that we can extend to art-workers in general. In particular, Kwon affirms that within a global framework, subjects are both located and oriented,5 able to fulfil multiple agencies within interstitial areas of intercultural contact. If our sense of identity is intimately linked to our relationship with places (Kwon quotes Lucy Lippard), the displacement caused by forced, as well as voluntary, (artistic) migrations risks weakening our ability to locate ourselves. Making the necessary distinctions, in line with Kwon, this dynamic gives rise to a feeling of belonging-in-transience:

[d]ispersed across much broader cultural, social and discursive fields and organised intertextually through the nomadic movement of the artist – operating more like an itinerary than a map – the site can now be seen as a billboard, an artistic genre, a disenfranchised community, an institutional framework, a magazine page, a social cause or a political debate.6

Hence, to better clarify this point, we can say that AWI has managed this local-global relationship by identifying instances, goals and interlocutors within its national context – basically, in close relationship with other organizations advocating for workers’ rights – and, simultaneously, by analyzing the harmful effects of unfair working conditions typical of late-capitalism by looking at and in dialogue with the international art community. Not by chance, we look with great interest at different initiatives, inside and outside the contemporary art world. The name Art Workers Italia underlines the convergence between these two dimensions in particular, although it is not directly inspired by the well-known experience of the Art Workers Coalition in 1969, it is certainly part of the cultural references shared by the group.

Generally speaking, given that “contemporary art production and its critical reception around the world can be readily identified with notions of ‘the global’ and ‘globalization’”,7 we are very much interested in working on the transnational aspects of our commitment by focusing on common points among different struggles. Indeed, to establish networks, foster the debate on art worker rights, and eventually support international solidarity initiatives, we are mapping AWI-like groups worldwide, a project we called, not surprisingly, HyperUnionisation.

Apart from this, there have been many occasions of exchange with those that we call “sister organizations”. To be more specific, for instance, the How To-roundtables are a case in point; in 2021, thanks to the support of the European Cultural Foundation and SMART - Société mutuelle pour Artistes, AWI invited different cultural practitioners from all over Europe to bring their experiences in three online meetings. They were conceived to provide conceptual tools to learn how to be better organized and politically recognized, namely How to Institute, How to Get Paid and How to Strike. Each roundtable aimed to pragmatically reflect on a specific theme or measure and to generate positive case studies to be potentially implemented in different countries and contexts.8

AWI, HYPERUNIONISATION, online platform, December 2020

What follows is a short selection of shared moments with “sister organizations” abroad that occurred over the years:

Aliens Networks (November 2023); an open conversation with the six grassroots organizations in the Nordic region, at OCA, Norway.

Vers une internationale des travailleurs*euses de l’art et au-delà (April 2023): international meeting of art workers organized by La Buse collective in Marseille.

Voices of Culture (April - June 2021); a platform for dialogue and discussion among 47 associations of the European cultural sector. The topics discussed focus on three macro areas: income and legal status of artists and cultural workers; mobility of artists and cultural workers; artistic freedom and freedom of expression.9

United we bargain, divided we beg (July 2021); organised by the Artists’ Association of Croatia in Zagreb.

Be Smart, Be equal. Challenges, paradoxes and exchange; gender equality in the visual arts (June 2021); organised by the Norwegian, Danish and Swedish Embassies in Rome.

In all these meetings and exchanges, and net of clear differences between the national circumstances, we received many expressions of solidarity. This leads us to think that, even if the problems are not the same – from a bureaucratic and technical point of view – a debate on the relationship between art and labor is definitely a shared desire at different latitudes – from the periphery to the centre and vice versa.

As artist Sepideh Rahaa states in an interesting conversation with curator Ceyda Berk-Söderblom on equity, inclusion, and social justice in arts and culture in Finland: “Not to remain silent is the best of my achievements. […] It is the ability to respond while echoing the already existing voices repeatedly.”.10

A significant amount of our energy was spent, in the beginning, in conducting an extensive and comparative study on the cultural governance already experimented with in other EU and non-EU countries to focus on the best practices and evaluate their applicability in Italy. The purpose, indeed, was to know more about the art workers’ status abroad but also to look at some useful tools to adapt to the Italian system. A case in point is an act to counterbalance the negative effects of the disconnection of income typical of our fields and, more broadly, of many self-employed jobs; inspired by the French legislation, the Italian parliament is currently analyzing its feasibility.

Activism as Care

Such an international flair stems from a systemic and intersectional approach to civil rights, which aims, according to what we claimed in our Manifesto, to an “egalitarian future”. As well as a safe place for contemporary art workers, AWI aspires to be a tool, quoting Judith Butler, “to imagine a world in which violence might be minimized, in which an inevitable interdependency becomes acknowledged as the basis for global political community. […] both our political and ethical responsibilities are rooted in the recognition that radical forms of self-sufficiency […], are, by definition, disrupted by the larger global processes of which they are a part”.11

Hence, we stand for civil rights when they are violated, such as in the current unfolding genocide of Palestinians by the apartheid and settler-colonial state of Israel.12 Some of our members have not shared the decision to support the Palestinian people and to stand against the violation of international law by Israel, not because of the demonstration of solidarity per se, but because they think it is a different struggle that doesn’t need our efforts. Instead, since its foundation, AWI has always declared solidarity towards marginalized subjectivities, which is not only just a good resolution but a concrete effort to create the conditions for a real inclusion far beyond symbolic gestures, performative activism and tokenism, namely beyond social class, gender, sexual orientation, disability, age, ethnicity or religion, nationality, the so-called “color line” and other physical features.

We cannot help but consider that we are living in a dark age where geopolitical relationships are ruled by a few whose models are not more sustainable from an economic, ecological, and ethical point of view. This is ominously fertile ground for violence and xenophobia everywhere and in all their declinations. Everything is connected; we are all part of the same public sphere, of the same “water”, paraphrasing David Foster Wallace13 and, as such, responsible, exposed and vulnerable; no one is safe unless we’re all safe.

The idea is that the precariat-based neoliberal system as a whole should be hacked, and we do it starting from our sector, from the dynamics we know and on which we can really/tangibly act, without forgetting that this sector is not a bubble and that, within it, any form of marginalization mirrors much wider logics. All the initiatives we take for the art workers, namely for those who are members and not (yet) members, are meant by the group as acts of care. Caring for someone also means caring for ourselves, namely, spreading values within a community we desire to live in so that everyone can benefit from it. It entails both

a cultivation of the self through the act of care [and] as a collective endeavor and way of being […], as a collective responsibility and collective act, performed and embodied by a community. […] The politics and ethics of care are less about the burden of responsibility, or the idealistic and “charitable” act of care that makes one a better person, and more about collective joy and fulfillment.14

It should be practiced critically and radically by keeping in mind the necessity to recognise not only one’s own privilege but also the risk of a one-way neoliberal charitable approach, whose only justification is the social inequality in which it is rooted. This is especially true for artistic institutions, so much so that one wonders, “how is it that contemporary art institutions are keen – and comfortable – to talk about care when they have been so care-less?”. This consciousness has brought us to go, paraphrasing iLiana Fokianaki, beyond “institutional critique” and towards a safer and healthier “institutional transformation”, which means beyond art for art’s sake and, sometimes, beyond art itself.

For further details regarding AWI’s actions, tools, research and more, visit our website and follow us on Instagram.

AWI, 2020