Illustration by Lotta Hagelin

Lotta Hagelin is currently studying Visual Communication Design in Aalto University and has a Bachelor’s degree in Arts. She focuses her work on issues related to the Sámi people, for example, by being active at street level, but also by participating in Sámi organizations and providing an indigenous point of view to a youth-led NGO called Operaatio Arktis.

In the colonial history of Finland, Sámis have been subjected to subordination by the authorities of the state of Finland and have suffered from asymmetrical power relations1. The continuity of colonialism can also be seen in contemporary Finland. The colonial mindset of owning, subordinating and exploiting a people is reflected in relation to the appropriation of Sámi culture. It manifests in the idea of taking - the dominant taking from the subordinate. Lehtola2 points out that in the Finnish context, colonial processes were not always based on purposefully negative intentions; however, there was quite a logical underlying way of thinking leading the actions that originated from the values of the dominant culture. Finnish cultural values reflect the prevailing mindset in Finland and how it views Sámi culture, design and cultural pieces. Sáminess is seen as a subcategory of Finnishness and, therefore, is controlled by it3.

Cultural appropriation refers to “taking from a culture that is not one’s own - of intellectual property, cultural expressions or artifacts, history and ways of knowledge”4. Cultural appropriation is not a new phenomenon in the Sámi context. Sámi handicrafts, duodji, have been and are still the subject of cultural appropriation. One of the central issues of cultural appropriation is that it gives the power to determine and decide on cultural objects to an actor outside the community, which weakens the self-determination of the community to manage the design themselves.

Finnish superstars using fake Sámi design

Sámi people have encountered many ridiculous, shocking and mind-blowing news articles in recent years about different cases of cultural appropriation and commodification when individuals, companies and associations have committed cultural exploitation. In 2005, Miss Universe Finland was wearing a fake Sámi dress in the Miss Universe competition,5 which received criticism mainly from the Sámi community. Every gákti, the traditional Sámi dress, is unique, contains details and information about the owner, and is traditionally made from degradable materials straight to its user. Sámis see gákti as their second skin, which reflects the significance of the garment. However, the same happened in 2007, when Miss Universe Finland once again wore a fake gákti to the competition6. The Sámi understandably criticized this, as it is not appropriate for either of the competitors to wear gákti or degrade the Sámi dress by wearing a copy. Customary law,7 based on the collective agreement of the Sámi community, defines the way of the use of Sámi products such as gákti, and one of the main guidelines is that only people with Sámi heritage can wear it8. Still, once again, in the 2015 Miss Universe competition, yet another non-Sámi Miss Universe Finland wore a fake Sámi dress to represent Finland.9

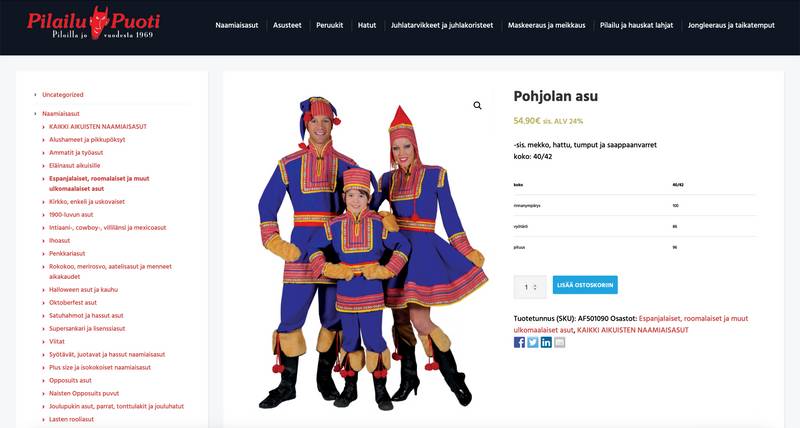

The Finnish Miss Universe representatives are not the only ones who have worn fake gáktis. A Finnish alpine ski racer, Tanja Poutiainen, wore a fake Sámi dress to their last alpine ski race in 2014 to symbolize the end of their career10. The fake gákti was a cheap version bought from a Finnish costume shop (Pilailu Puoti), which can still be purchased, despite all the criticism, on their website with the name Pohjolan asu, ‘Nordic costume’. Other pieces of Sámi culture have been appropriated too, for example, the šávka, or star hat, used by Lordi when they won Eurovision in 200611 12 and by Lumi Accessories in their marketing imagery in 2017.13

Duodji, which these products such as šávka and gákti are part of, is a crucial part of Sámi culture and, together with reindeer herding, hunting and fishing, is one of the traditional livelihoods of the Indigenous Sámi People. The practice of traditional duodji is still well known in the Sámi communities, but duodji has taken on new, contemporary forms, too. Guttorm describes duodji in a way that emphasizes the broadness and meaningfulness of the concept: “Duodji is all forms of creative expression that require human thought and production”. Sámi duodji has indescribable meanings for Sámis, which makes it insulting to see fake Sámi clothing sold at costume shops.

These triumphant Finnish heroes who put on inauthentic Sámi dresses and bathe in the limelight often say that they bring glory and visibility for Sámis by wearing fake pieces of Sámi design. We also often hear that we should be grateful that our culture is on display at all. In turn, when Sámis get dressed in gáktis, we are automatically exposed to an increased amount of racist comments. The exploiters of culture take only the visual, beautiful pieces about the Sámi culture without having to face, for example, hate speech, ethnostress or racism.

Screenshot from Pilailu Puoti website

Duodji is based on making the products functional in Sápmi, and it is rooted in a circular economy. The circular economy reflects the traditional Sámi way of thinking too - everything that we take, use or consume has to be used completely. For example, when a salmon is caught, we don’t only eat the fillet, but also make soup out of the bones, and on top of that, the skin can be used to make duodji. The same goes with reindeer - the reindeer is not only taken for the meat but also using, for example, reindeer leather to make duodji. Far from being products that have meaning and are made directly for the wearer, inauthentic Sámi dresses are cheap copies made in factories.

These triumphant Finnish heroes who put on inauthentic Sámi dresses and bathe in the limelight often say that they bring glory and visibility for Sámis by wearing fake pieces of Sámi design. We also often hear that we should be grateful that our culture is on display at all. In turn, when Sámis get dressed in gáktis, we are automatically exposed to an increased amount of racist comments. The exploiters of culture take only the visual, beautiful pieces about the Sámi culture without having to face, for example, hate speech, ethnostress or racism.

On huge platforms, such as the Eurovision contest, the Miss Universe contest, or the World Cup, the individuals are eventually representing their home country too. By wearing an object of Sámi culture as an individual, Sámi culture is straightaway tied to Finnish culture too, which falsely once again makes Sámi culture a subcategory of Finnish culture. Sámi culture is not Finnish culture.

Creating a distorted image of the Sámi people in the tourism sector

A similar misleading image is created in the tourism market, where Sámi culture is portrayed as part of Finnish culture. In the Finnish tourism field, the exploitation of Sámi objects and culture for commercial purposes and advertising is existent,15 for example by selling cheap, low-cost production souvenirs. In the discourse of marketing Indigenous Peoples to the tourism market, it is common to emphasize and use stereotypical images of Indigenous Peoples.16 This applies too to the tourism market, where Sámi culture is exploited, and the imagery, of course, creates a fallacious perception of Sámis for non-Sámis.

Fake Sámi design also has a negative impact on Sámi identity and self-image as Sámis are often portrayed alongside inauthentic duodji in a derogatory and antiquated way.17 Sámi people are influenced by distorting imagery, and the misleading images gradually affect the Sámi people’s perception of who we are. Cultural appropriation also offends the Sámi people’s right to self-determination in how the culture and people are displayed.

It is very contradictory that, while the Sámi language, culture and people have been and are subordinated, Finland keeps promoting Sámi people in the tourism sector. At the same time, behind the scenes, Finland itself is failing to promote indigenous rights of the Sámi.18 Moreover, for instance, our cultural artifacts have been destroyed because they have been considered pagan. Now these fake “pagan” products are sold in tourist shops at a cheap price. Colonial structures are still alive - the culture is being exploited once people have found yet another way to benefit from the culture.

If morality does not prevent cultural exploitation, laws should

In today’s world, it seems that the ethics of the process and the product are less and less valuable when it comes to making money. One could imagine that if morality does not prevent cultural exploitation, laws would safeguard the existence and maintenance of Sámi people’s cultural products.

Article 17.3 of the Constitution of Finland implies “Sámis as an Indigenous People’’ which broadens the juridical dimension of international law regarding Indigenous Peoples.19 For instance, it is mentioned in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that “Indigenous Peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their - - traditional cultural expressions, - - designs, - - traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.20 Moreover, “states shall take effective measures to recognise and protect the exercise of these rights”.21 However, Finland’s reluctance to commit to international law relating to the rights of Sámi people is still evident in Finnish society. This is reflected, too, in the fact that Finland has still not ratified the ILO169 Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, which, among other things, would guarantee Indigenous People the same rights and opportunities as the majority population. The failure to improve the rights of the Sámi is also evident when it comes to implementing national law since the Sámi Parliament Act has still not been implemented.

To sum up, not only is it ethically right, but Sámis also has the juridical right to be protected from cultural appropriation. In practice, however, this is poorly achieved. Still, the Sámi people’s rights are not respected in Finland22 23, which is also reflected in the fact that cultural exploitation is present in Finland. After all, Sámi people have already created other ways of identifying and thus safeguarding authentic duodji since the 80s.24 Different Sámi Trademarks such as “Sámi Duodji” and “Sámi Made” guarantee that the product has either been made by a Sámi or is genuine duodji.

Pretendians and cultural appropriation

As the race-shifter phenomenon has taken hold globally, not only individuals and companies but also wider communities have exploited Sámi design as a countermovement has emerged in Finland to seek to construct, define and challenge Sáminess.25 A pretendian is “a person who falsely claims to have indigenous ancestry, who fakes an indigenous identity, or who digs up an old ancestor from hundreds of years ago to proclaim themselves as indigenous”.26 Basically, identifying as a Sámi is not only a question of self-identifying as one but also a question of group identification.27 The indigenousness cannot be justified by ancestry from hundreds of years ago without present connections.28 Duodji is being exploited in Finnish Lapland by pretendians who copy, for example, different gákti models, colors and materials and have introduced new variations of gákti.29 The authentic gákti models vary by area; for example, on the Finnish side of Sápmi, Eanodat-gákti and Ohcejohka-gákti are different.

According to the non-status Sámis, as one group of the countermovement calls itself, their gákti models follow certain models that belong to their Sámi lineages.30 However, these lineages are unknown for Sámis, and these claims and the quality of the evidence have been disproved.31 32

Copying gáktis is harmful to Sámi culture in Finland since for non-Sámis these fake-gáktis look authentic. For the Sámi, however, these fake Sámi dresses are classified as inauthentic because the common rules within the Sámi community form guidelines for gáktis and its different models. Since the pretendians maintain the discourse of being an oppressed people within the Sámi community,33 the fake gákti reinforces their representation and imagery as a “Sámi people” to outsiders who are not familiar with the countermovement phenomenon. The pretendians get more credibility to challenge Sámi people’s status and so-called rights in Finland. By appropriating Sámi duodji, the pretendians fake their way to look authentic and thus gain more power to be taken into account in decision-making.

Also, as a symbolic gesture, copying gáktis is offensive to the Sámi community. Due to assimilation politics, depreciating and being taught to be ashamed of Sámi culture, some families within the Sámi community have stopped wearing gákti. However, younger generations who belong to families that have lost the tradition, including me, have started to revive the tradition. The process is possibly done together with older relatives. Revitalizing the tradition is, of course, linked to the wider process of having to face the outcome of assimilation and colonization - transgenerational trauma. As Guttorm34 summarises: “Today’s koftes [gáktis], and Sami clothes in general, carry with them a history of the Samis’ life and communication with each other and the outside world“. It is definitely insulting that the pretendians take the privilege of falsely reviving gákti without having to wear it while dealing with these possibly painful dialogues with the outside world, both in the past and in the future, and having to face the scars of assimilation and colonialism.

How to exploit Sámi design and make it trendy

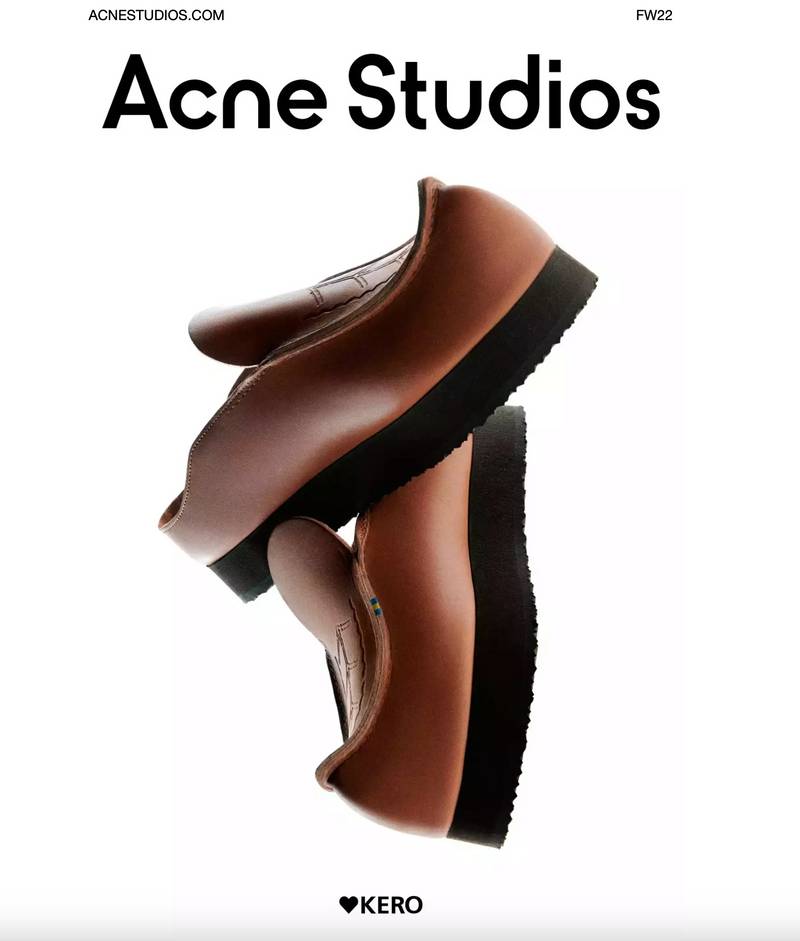

As the list of cultural appropriation of Sámi design goes on, one occasion that pops out is when Acne Studios made a collaboration with a Swedish brand, Kero, that makes traditional Sámi inspired boots from reindeer leather. On October 2022, Acne Studios presented the collaboration on their website: “Acne Studios is presenting their own take on the Sami beak”.35 Acne Studios used the traditional Sámi boots, čázehat, as a source of inspiration for a new collection. In other words, Sámi culture was exploited and exoticized by making Acne Studios’ pair of boots attractive by calling it a product with a touch of Sámi culture.

Screenshots from Acne Studios website

Not only Acne Studios, but Kero too, is responsible for cultural appropriation by accepting the collaboration with Acne Studios. By cooperating with a massive company, they are accepting business and selling a traditional Sámi product for the modern season-based fashion industry. The modern fashion industry is based on seasonal manufacturing, making huge stocks of products mainly sold on the basis of their appearance. Once the product is made compatible with contemporary fashion, in the next seasonal collection, it is already out of style. This too is very contradictory when considering the Sámi way of thinking. Čázehat never go out of fashion.

One concern about cultural appropriation is that it wrongly allows some to benefit financially from the material detriment of others.36 In the Acne x Kero case, Sámi design is seen as a financial instrument to accumulate wealth for the companies and leaves the Sámi community out of benefiting from the products. However, in Sámi culture, čázehat has many other values, meanings, and purposes beyond being a capitalist good, which is why it is offensive to make money out of this pair of boots.

However, months later, when these two brands had published their collaboration, the advertising campaign was changed to “boots feature a traditional Swedish beak shoe construction (28.7.2023).37 It is true that others than Sámis have used beak shoes and this has happened on the Finnish side too. The peculiar thing is that the source of inspiration in the collaboration changed from Sámi culture to Swedish culture during the advertising campaign. As two Swedish companies, they cannot be accused of cultural appropriation anymore since the Swedes have used beak shoes too. The companies have still crossed the line between taking inspiration and committing cultural appropriation. It is the company’s responsibility to take ethical considerations into account in product design.

One concern about cultural appropriation is that it wrongly allows some to benefit financially from the material detriment of others. In the Acne x Kero case, Sámi design is seen as a financial instrument to accumulate wealth for the companies and leaves the Sámi community out of benefiting from the products. However, in Sámi culture, čázehat has many other values, meanings, and purposes beyond being a capitalist good, which is why it is offensive to make money out of this pair of boots.

A year later, the collaboration has still not been called out. As a Sámi, in fact, I am not surprised by this since the continuity of our culture has been in the hands of individuals since the colonization of Sápmi. In general, the knowledge and understanding of Sámis and Sámi culture is almost nonexistent,38 and identifying cases that are damaging to Sámi culture is difficult for those who are not familiar with the challenges that the Sámis confront in society. The lack of knowledge prevents issues related to indigenous rights themes from being properly addressed in Finnish society and by Finnish politicians.39

I see the Acne x Kero collaboration as a turning point in the way Sámi design is framed and perceived in advertising. In the Acne Studios advertising campaign, the boots were photographed on a ‘Sadboys’ artist Bladee, which automatically made the shoes up-to-date and cool. Acne Studios as a brand can be considered hot and trendy too. In turn, Sámis have been mocked for the way we dress and what kind of clothing we use. It is contradictory that, having gone through a Western capitalist design and marketing process, suddenly the Sámi inspired product becomes desirable. If similar kinds of clothing and shoe collections are repeated, they will eventually be done at the expense of the Sámi community, just as before. Are we heading towards a period when indigenous and other non-majority cultures will be seen as desirable and trendy?

Deconstructing colonial power relations

The appropriation of Sámi design and culture is linked to colonial structures and the misuse of power, whether intentional or not. Often, when Sámi people criticize incidents of cultural appropriation, hate speech and misinformation increase, both in online discussions but also in the mainstream media. This was proven again in December 2023, when Sámi people criticized a work of art that is due to come to Lux Helsinki in early 2024. The work stereotypes and exploits Sámi culture. The colonial structures are therefore still very much in place today.

However, it must be taken into account that more and more often, representatives of the majority population also defend the Sámi when cultural appropriation occurs. In reality, in addition to the exploitation of Sámi design, Sámi lands, waters and culture are also being exploited. Calling out fake Sámi dresses and shoes are just cases in addition to preventing green colonialism in Sápmi, stopping wind power projects that break our human rights, reviving Deatnu salmon and strengthening the self-determination of the Sámi. We still need stronger recognition of colonial structures and asymmetrical power relations in our society.