Illustration: Psycollagist

Fast-evolving Internet culture is shaping and influencing the ideas of contemporary India. Memes and other Internet art have come forward as crucial tactics in combating the psychological warfare between the online and offline worlds. They act as neural network attractor states in the brain, infiltrating our thinking system (and populating our screenshot folder) and seducing us into tips, tricks, and problem-solving. In this context, I will discuss meme culture, misinformation, trolling, and data-muddying in times of pandemic and war using the visual language of digital artworks created and circulated by meme-makers, meme-collectors, anarchists, radical thinkers, writers, poets, friends, lovers, cats and dogs [just kidding].

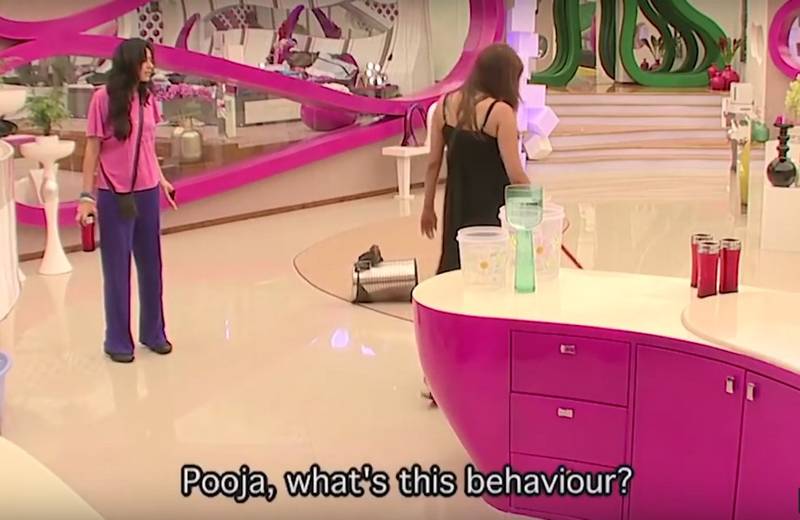

Right before the pandemic hit, the television landscape was a curious mix of exaggerated relatability of low-income breadwinners, Indian Premier League extravagance, screaming news anchors and the rut of soap operas. While citizens were surfing the waves of punitive zeal in response to the rise of Hindutva politics, new connections are forming between the pits of human psychology – prodded by close-circuit and movement-restricted program concepts on Indian television and OTT platforms. In line with regressive values prioritized in BJP-led India for some time now, the rising popularity of shows like Comedy Nights with Kapil Sharma, or reality TV programmes like Big Boss, where voyeurism, abuse, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, and body shaming have been a theme of a ‘joke’, is dinner-time “family” entertainment. The idea of reality TV stars and the small town Bollywood achiever narrative had simultaneously made exposure across class barriers easy, along with referencing some of those ideas of how we behave due to those markers, even before the current political climate and Covid took hold. This factor is crucial because it has given the “entertainment consumers” a vent through the carnivalesque. Meme culture in India has grown as a popular way to consume and critique Bollywood, TV and politics, the intersections of which can be used to understand what life is like for citizens living in a new normal state of fear of repercussions in a communally charged country. A scene from the Indian reality TV programme Bigg Boss now popularly known as ‘Pooja, what is this behaviour?’ became a viral meme within India and the Indian diaspora. Pooja here is all of us, provoking and prodding at our “behaviour”, referring to how we consume media and how mediatized environment shapes our politics.

We live in an era driven by information and technology, constantly refracting or replicating other information to provide fodder for conversations surrounding cultural phenomena. In this sense, Internet memes are furiously driven by the minute to comment upon anything from how we see the colours of a dress to how we understand political currents.

What do you meme?

Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme”, which has been widely adopted (and disputed) in many disciplines, including psychology, philosophy, anthropology, folklore, and linguistics. But for most of the twenty-first century, it was utterly ignored in the field of communication. Only recently, mass communication researchers have rapidly grown comfortable with imagining the radical scope of the meme as a fragment and fortune of human socio-political consciousness. But this is no longer the case in an era of blurred boundaries between interpersonal and mass, professional and amateur, and bottom-up and top-down communications. In a time marked by a convergence of media platforms, when content flows swiftly from one medium to another, memes have become more relevant than ever to communication scholarship.

We live in an era driven by information and technology, constantly refracting or replicating other information to provide fodder for conversations surrounding cultural phenomena. In this sense, Internet memes are furiously driven by the minute to comment upon anything from how we see the colours of a dress to how we understand political currents. Researchers like Jean Burgess have used memes to understand certain aspects of contemporary culture without embracing the whole set of implications and meanings ascribed to it over the years. Highly stylized and often shrewdly shrouded in what is ostensibly ascribed to the opposite of high art, memes are artefacts of pop culture that merit a deeper look at how they engage, dictate, and draw resolutions from public opinion.

The relationship between public opinion, media freedom and digitisation drives (e.g. UIDAI, Right to Privacy Laws) are critical in understanding the innovation drive and the path of resistance in the last ten years in India. Rapid adaptation of technology by the state as an ostensible way to aid welfare has not been without criticism regarding privacy mishaps, problems with maintaining and linking data on welfare schemes, and an overall sense of doom regarding it all. The Pegasus debacle was recently added to the lay understanding about dystopian information technology apps by parties who can make such investments into unethical strategies. Planting evidence to justify incarceration, curtailment of the rights of citizens, depreciation of the country’s morale, and upturning constitutional guarantees have been their POA, as seen in political events of the country in the last six months. Human Rights Watch has reported on the increasing criminalization of peaceful expression in India and said that the government uses draconian laws such as the sedition provisions of the penal code, the criminal defamation law, and laws dealing with hate speech to silence dissent. More recently, the “bulldozer” is replacing the lotus as BJP’s election symbol.

The heavy machine has come to symbolize the current regime’s hate, power, and ideology. The image of the bulldozer quickly became a meme for the political discourse on Twitter whenever there would be an issue related to the marginalization or vilification of the minority community in India. Nevertheless, text messaging apps and social networking websites have also allowed quicker communication to resist the fraught and foggy world of privacy, even in the face of the quick-spreading fake news and propaganda.

Clubhouse and new adda for public discourse, engagement and citizen-led cooperation

In the toxic and unfeeling relationship that the Indian government has with its citizens, the year 2021 marks ongoing mass-gaslighting exercises, a systematic breakdown of public vigour and health, and wanton incarcerations of activists, civil society leaders, journalists and students. Add to it the expansion of a corporate police state rising over the constitutionally-protected rights of the people and the revision of history – learnt and acknowledged by children and adults alike. Smothered in this choke, I found myself on Clubhouse during the second wave of Covid 19 that bookended 2021.

As citizens, we had been unwilling witnesses to the complete desecration by the ruling party’s false narratives and violent ideology for quite some time. In such an environment, Clubhouse quickly became popular among those eager to gather and engage. The rooms and topics were entertaining and poetic. Participants in “Rooms” sang lullabies, recited poetry, shayaris, cracked jokes, read excerpts from novels, and even did a catching-up gupp-shupp on current affairs; many shared links to crowdfunding and citizen initiatives for organizing resources amidst the pandemic. It emulated the feeling of being at an adda.

Clubhouse is an audio app where members create “Rooms” and topics to talk with anyone from across the globe. There are no time limits. The app quickly logs you in, and you add a profile picture and a bio section for linking to other social media handles. Because of its simplicity and potential for high-level engagement, the application quickly gained popularity among new users, granting common people the autonomy of their voice. As citizens, we had been unwilling witnesses to the complete desecration by the ruling party’s false narratives and violent ideology for quite some time. In such an environment, Clubhouse quickly became popular among those eager to gather and engage. The rooms and topics were entertaining and poetic. Participants in “Rooms” sang lullabies, recited poetry, shayaris, cracked jokes, read excerpts from novels, and even did a catching-up gupp-shupp on current affairs; many shared links to crowdfunding and citizen initiatives for organizing resources amidst the pandemic. It emulated the feeling of being at an adda.

Clubhouse served as a coping mechanism and a therapeutic outlet. I’d open the app daily at noon, talk to strangers, eat meals, sing, argue, speak, cry, and fall asleep. This new feeling of listening and conversing with strangers felt oddly comforting. It made me happy and less anxious and gave me the relief I needed. It provided unexpected new work connections, friendships, and even times for love. In my club, Bhang Ki Dukaan, I raised over 11 lakh Rupees through the two-week Covid Relief campaign, which was a highly intense, dangerous, and uncertain time in India. We were waking up to calls, texts, emails, WhatsApp messages, Tweets, and Instagram DM’s, with desperate requests for oxygen tanks, hospital beds, and medicines. It was heartening to see strangers trying to help each other without ever meeting IRL. Rising from a collectively fatigued political consciousness, strangers helping each other without meeting IRL was heartening to see. It was a new feeling of having the urgency of meaningful connection and collaboration – a momentary disposition and a sense of unity that we wanted to cherish.

Clubhouse’s rapid popularity in the second wave of Covid-19 was located in the sullen acceptance that the governing administration had failed its citizens and in the cindering expectations of empathy. A year later, the audio app now struggles to have enough users and influencers who can engage with other users or create meaningful audio content. After the health security restrictions and guidelines were eased, Clubhouse suffered a sharp drop.

Memes as Political Participation and the Toolkit of Digital Resistance

India’s youth who were promised jobs, higher incomes, and opportunities back in 2014 are now grappling with economic uncertainty, unemployment, inflation, and climate change. The poster child for the liberalized economy, they are now the new losers of globalization. Political campaigns like “India Shining”, “Make in India”, “Vocal for Local”, and “Acche Din” by the right-wing party BJP have become memes for political discourse and participation. The promises have long been forgotten, and a dream sold to them never materialized – yet it keeps being offered up. In her book, Dreamers, Snigdha Poonam, writes that in 2016, 9.2 million young Indians sat entrance exams for 18,252 railway positions, while 19,000 competed for 114 public sector jobs in one small town. “Thousands of college graduates, some armed with engineering and MBA degrees,” applied to be a sweeper. Poonam further argues that these young Indians who find themselves conned will now be the “leftover youths whose anger is transforming world politics.”

In India, memes are simultaneously being used to resist fascism and create a positive outcome, as well as disinformation campaigns aimed at smearing opponents. Naturally, meme strategies are also being used for propaganda to reinforce radical ideologies, nationalistic identities and discriminatory stereotypes, hyper-produced and circulated via troll ‘factories’ and bots that tout propaganda as genuine-appearing propaganda content.

If one looks at the disturbing results of the globalized economy of India, there is more unequal growth than the US and even angrier politics. This has given rise to political humour, memes, and satire. In the current oppressive regime of India, memes are flourishing. Memes symbolise cultural reproduction driven by various methods of copying and imitation. Internet users have understood that the meme concept encapsulates some of the most fundamental aspects of contemporary digital culture. Like many Web 2.0 applications, memes diffuse from person to person but shape and reflect general social mindsets. There is a sharp rise in paid bloggers, Twitter accounts, and commentators being hired to generate content and create images and opinions in the mind of the people for every issue.

In India, memes are simultaneously being used to resist fascism and create a positive outcome, as well as disinformation campaigns aimed at smearing opponents. Naturally, meme strategies are also being used for propaganda to reinforce radical ideologies, nationalistic identities and discriminatory stereotypes, hyper-produced and circulated via troll ‘factories’ and bots that tout propaganda as genuine-appearing propaganda content. In the Indian farmers’ protests of 2020-2021, we saw many examples of how Internet communities were formed on various social media platforms to debunk propaganda memes. It felt like collective action that could be engaged across class, caste and gender roles. The digital resistance facilitated decentralized methods to consume and circulate information. Not just because of this, but eventually, the government rolled back the insidious farm laws after almost one year of farmers sitting in protests at the national capitals adjoining borders.

Formal modes of engineering the well-being of the population are oppressive and exclusionary. Activists, scholars and citizens of the world have to find compassionate and strategic ways to enact their power of adaptability. Memes allow us to challenge conventional and restrictive forms of education, policy and collective action, fostering effective solutions for a broken system. Memes, as the new toolkit adopted by Internet users of India, has the potential to nurture democracy and pluralism, with the hope to preserve freedom of speech, freedom of expression, and freedom to resist. So the next time your colleague sends you a “good morning” WhatsApp propaganda message, instead of disproving them, you can just say, POOJA, WHAT IS THIS BEHAVIOUR?