From a protest at Tengnoupal district in Manipur, India.

Greeshma Kuthar is an independent lawyer and journalist from Tamil Nadu. Her primary focus is investigating the evolving methods of the far-right, their use of cultural nationalism regionally and their attempts to assimilate caste identities into the RSS fold.

A video first surfaced within Manipur in July of 2023, where two women were being paraded naked by a mob of men. The video was of an incident that had occurred on May 4. The fact that it took two and a half months for the incident to be reported by any mainstream news organisation isn’t the only shocking aspect. An FIR registered by the affected families in May mentioned the presence of the state police during the incident. Yet, the brutal act was left to fester as if it never occurred. “In 2006, 21 Hmar women were sexually assaulted by Meitei insurgents. Tribal women have borne the brunt of several such cases, yet in those cases, we could attempt to at least arrest the culprits as we were considered part of the state. It is different now. The state government is fighting us. The question of dignity or justice for us is absent,” said Jessica Mawi, a writer from the community.

“Although the violence had been precipitated by the Manipur High Court directing the state government to expedite the longstanding Meitei demand for Scheduled Tribe status, the order came amid an escalation in the Biren Singh government’s concerted campaign to stir up majoritarian sentiments against Kukis, using the same tactics it had employed against the Pangals (Meitei Muslims).”

– from Greeshma Kuthar’s cover story in August 2023 for The Caravan titled Fire and Blood: How the BJP is enabling ethnic cleansing in Manipur | Read the full excerpt here

It had been more than two months since the ethnic violence started, and by then, such images of violence, gunfire and killings had become commonplace in the state. This video, though, was shocking even to look at; it was visual evidence of what was being said by Kuki-Zo women for weeks. Sexual violence has been an intrinsic part of the ethnic violence they had been subject to since May, although no one, especially the Union government, had been willing to listen. The next day, the video was shared on X [formerly Twitter], where it garnered international attention overnight. Manipur was finally in the news, albeit for a really short period.

Delayed attention, denial of justice

In the weeks following the video going viral, national and international media organisations were suddenly flooding Manipur – demanding that they be allowed to meet and talk to victims of sexual abuse, forcing them to recount their abuse on camera. During one such pursuit by an international agency, I witnessed a few Kuki-Zo women leaders fighting back by refusing to agree to such representation and insisting that the victim’s lawyer be interviewed instead. But their opinion wasn’t taken into consideration. Male leaders of the community who had permitted such interactions before, oblivious of the problematic nature of such interviews, said, “The women have already given interviews; how does a few more matter?” The men took the journalists to the victim, and she was made to recount elaborately how she was sexually assaulted in Imphal all over again.

Protests were organized demanding justice across Kuki-Zo districts in the wake of the viral video.

Prayer during the protest. Protests were organized demanding justice across Kuki-Zo districts in the wake of the viral video.

Whether this was a women’s issue, a tribal issue, a human rights issue, a Manipur issue, or a national issue didn’t necessitate the enquiry of ‘why the dignity of these women, being subject to such treatment and representation, didn’t figure in bringing the conflict to an end’.

As I attended different protests organised by other communities in the following weeks, a few Meitei women I spoke to were quick to condemn the incident in no uncertain terms. Unfortunately, these were just a handful. A majority of women I spoke to shockingly justified the incident, indulging in slut-shaming Kuki-Zo women and alleging that tribal women are used to being ‘loose’1.

There were also insensitive appeals by Meitei men urging their women to come forward with accounts of sexual assault by Kuki men to ‘protect the dignity of the community’. One Meitei woman from Bishnupur eventually filed a police complaint, claiming that she was sexually assaulted, prompting an investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The CBI is currently probing all cases of sexual assault.

Protests by Naga women groups condemned the incident but were reluctant to question its structural nature. While decrying it as a failure of the police apparatus, they declined to get involved with the question of how huge mobs were emboldened by the Manipur state to carry out such a depraved act.

While there had been an instance of Naga women students being molested and more Naga women were subject to violence in the Valley in the months to follow, civil society organisations orchestrated out-of-courts settlements, and the issues quickly closed. The victims told me that they were opposed to this, questioning why their self-respect and dignity weren’t considered important to address.

For Kuki-Zo women, even organising a protest where they could express their struggle was difficult. In Kangpokpi, as women leaders unaffiliated with political groups organised a rally demanding justice for the victims, male members of various Civil Society Organisations engaged in a scuffle, demanding centre stage at the event. In the months to come, I saw many women question their own role in the community and refused to acknowledge their leadership in rebuilding a society riddled with war. As the violence continued, many women were disheartened. But they prioritised the needs of the community when necessitated.

Kuki-Zo women did not have the time or the space to grieve the lack of justice and dignity. Yet instead of being reduced as victims, many of them were actively working to support their community—especially by ensuring access to education—as they confronted widespread denial of state services and constitutional rights.

In Kangpokpi, as women leaders unaffiliated with political groups organised a rally demanding justice for the victims, male members of various Civil Society Organisations engaged in a scuffle, demanding centre stage at the event. In the months to come, I saw many women question their own role in the community and refused to acknowledge their leadership in rebuilding a society riddled with war.

A mother and child take a break from prayer service at a church in Saikul, organised on Christmas eve. There were no Christmas celebrations in the Kuki-Zo districts.

Uncertain futures amidst state apathy

Hemkholen Touthang recognised me as soon as he spotted me from a distance. Waving at me, he posed his customary “How are you Miss?” to greet me, while grinning, followed by “Had your food?”

These are two questions he would always ask me whenever I would call him for updates about the situation of the people along the Manipur river. Hemkholen has been a boatsman for over three decades.

“Very difficult, Miss, still very difficult,” he said as he climbed into his boat, preparing to cross the river. He would do almost 12-hour shifts, as there was no other way for people to quickly go over to the other side but by his boat. “I am a social worker, Miss, we make no money,” he said. Yet, he said his work was very important, as even for accessing basic essentials or the closest market to sell produce, crossing the river was the only option. This was at the peak of winter in December.

When I met Hemkholen in June 2023, he seemed troubled. Along the river lie Sugnu and Serou, the two towns that saw widespread violence in May. The only bridge that would help people flee from the Kuki-Zo localities was burnt down, and many had to turn to the river as they fled.

As Hemkholen helped some of them across the river, he was reminded of the other wars he had lived through, one between the Nagas and Kuki-Zo, the other within tribes of the Kuki-Zo. During both these wars, he helped rescue people, rowing them from the Lamka side to the Chandel side, and vice versa. He had been a mere observer, he told me, but he was and remains very scared for young people. Every time I met him, he hoped that the war would end soon. “No schools, no medicine, no food here, Miss.”

As Hemkholen helped some of them across the river, he was reminded of the other wars he had lived through, one between the Nagas and Kuki-Zo, the other within tribes of the Kuki-Zo. During both these wars, he helped rescue people, rowing them from the Lamka side to the Chandel side, and vice versa.

Hemkholen Touthang lets a passenger take the ropes as they cross the Manipur River

“It took us more than a month to understand the scale of violence. Not only were we being attacked, but we also had nobody to turn to,” recounted Veijakim, an educator from Kangpokpi who runs a school founded by her husband, Dennis Misao. Within weeks, they both realised that as society saw polarisation, so did state institutions.

Headquartered and controlled from Imphal, these institutions were dangerously being used against the Kuki-Zo community under the direction of Manipur’s Chief Minister N Biren Singh. The first such visible partisan behaviour was that of the police, who have been photographed and video-graphed supporting armed Meiteis, as they would orchestrate violence in Kuki-Zo villages. For over a year this has become common practice across government departments, such as in electricity distribution and education. Kuki-Zo districts would see power cuts spanning for weeks, yet there would be no immediate intervention from the state. All Kuki-Zo students studying in schools and colleges in Imphal, including state and central universities, had to flee the city, but most of them have yet to receive support from the government to continue their education or even obtain a transfer certificate.

Displaced Kuki-Zo medical students protest at Churachandpur Medical College, Manipur

A school in Kangpokpi district of Manipur

A school that was burnt down in the border town of Moreh

Residents of Motbung line up to pay their tributes, as a funeral procession passes by

Educators like Kim and Dennis were victims of such state apathy in the early days of the violence. The primary challenge they faced included the correction of pending board language exam papers of Kuki-Zo students.

Security agencies had to step in just to ensure that the answer sheets were checked, marked and transported safely to and from the Board offices to the districts affected by the violence. Displaced Kuki-Zo students could not physically collect certificates and mark sheets, as travelling to the Board offices in Imphal was out of the question. Many videos emerged on social media where individuals were seen burning certificates, mark sheets, laptops and written work of Kuki-Zo students, raising serious concerns about the safety and security of academic records. Equally disturbing were images of schools being burnt down.

In this backdrop of civil unrest, Dennis, along with 70 other school owners functioning under the state government, sought affiliation of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE). “ In times of great distress, the need for a stable and recognized curriculum becomes paramount, and the CBSE affiliation seemed to be the only beacon of hope for us,” explained Dennis. After an arduous application and verification process, 26 out of the 71 schools that applied were granted CBSE recognition. Almost overnight, the state government intervened, alleging that they were not informed about the process. The ‘No-Objection Certificates’ (NoC) which these schools had obtained from the Kuki-Zo zonal officers were termed ‘fraudulent’, and eventually the affiliations were withdrawn by the CBSE. The zonal officers who granted the NOC were suspended and forced to tender apology letters. The state criminalised any attempt to safeguard the future of the 30,000 students. However, this was never highlighted, neither was the struggle of these tribal educators who were subjected to state harassment.

These educators felt betrayed, not just by state institutions but also by their own leaders who remained indifferent to the plight of the students. However, Dennis and Kim refused to drown in self-pity like others. “We will have to question our own choices, be it in choosing our leaders, or whether we [have] got the government we deserve.”

Most women leaders who spoke to me about these skirmishes felt that if they were in leadership positions, they would have dealt with it differently. Taking up a leadership role was a reasonable demand they felt as they played a decisive role in working through the war and rebuilding lives. But their efforts were never acknowledged and neither were their insights taken into consideration.

Conversations on leadership, or the lack of it, have repeatedly surfaced in the public discourse since the onset of violence in the hill districts. Many were afraid to speak up because the civil society organizations chosen to represent the community were backed by insurgent groups, which used their armed influence to intimidate them into submission.

Almost all elected representatives are either directly affiliated with these groups or are supported by them. Those who defied them either faced threats or were subjected to violence. But the more concerning aspect of this was the absence of women in the decision-making. “Men guard their leadership positions as sacrosanct and are not ready to acknowledge the contribution of women to the level where they have to share a space in leadership, said Kimneijou, a scholar and activist from Haipi, referring to traditional patriarchal structures that make up Kuki-Zo society.

However, patriarchy prevails within the leadership positions. Villages within the community are governed by a single chief, who can only be a man, a rite passed on to male descendants only. Jou felt that this patriarchal position of power has translated from traditional social orderings to modern democratic spaces as well. Men prefer conforming to society and are not yet bold enough to break the mould. “I guess it is very difficult to give up these privileges hence, they choose to turn a blind eye,” observed Jou, reiterating that the community is stuck because of such a patriarchal mindset and an unwillingness to share leadership or acknowledge differences of opinions. “This also means we are denying possibilities of all kinds of reform to our community.”

This conversation became all the more relevant as many instances of infighting within the Kuki-Zo tribes emerged over the past few months. Most women leaders who spoke to me about these skirmishes felt that if they were in leadership positions, they would have dealt with it differently. Taking up a leadership role was a reasonable demand they felt as they played a decisive role in working through the war and rebuilding lives. But their efforts were never acknowledged and neither were their insights taken into consideration. “You’ll hardly find any women in the Kuki Inpi Manipur (KIM), an apex body of Kuki tribes. The only spaces for us, with very limited roles and responsibilities, are groups such as KWU, KWOHR, ZWC,” said Ngaipilhing Alice, a civil rights activist from Lamka. Alice reiterated that handing over power to women would have minimised the infighting. “Internal conflicts would definitely have been much less,” she pointed out.

Under the condition of anonymity, a senior woman leader told me that the critical decisions on how to aid the displaced during the war were being made by incompetent leaders.

An independent researcher, Breeze lived in relief camps to understand the needs of those internally displaced by the ethnic violence. Wherever possible, she tried to provide whatever resources she could including tutoring the students. “At times, it is better to just lend an ear. We do not even understand their ordeals enough, as everybody from the community has a lot to cope with at the moment,” Breeze shared while also highlighting the limitations of providing mental health care to the displaced. Volunteers like Breeze were witness to the acute lack of resources in the relief camps spread across hill districts.

Among the displaced, at least 70% from Imphal – who were more affluent – have been able to pick themselves up and fend for themselves, observed Dr Mary Grace Zou, Convenor of the Kuki-Zo Women’s Forum, Delhi. But the displaced working class people were forced to live in relief camps.

“The disparity within the displaced is something we have to recognise to be able to work for those that need most help,” explained Dr Grace, pointing to the nuances that outsiders cannot grasp.

In Kuki-Zo society, each unit consists of individuals who are allocated land by the village chief for living and cultivation.

This unit is self-sustained, deciding on most matters concerning their land by themselves through a governing council. When the land is taken from the unit, their landlessness fuels a loss of identity and resources. Many of the villages which have been burnt down, now face this loss of identity “To remedy this situation, we will need other village chiefs to step in and share their land,” said Dr Grace. This has already happened in a few villages.

The Kuki-Zo community has supported its internally displaced almost entirely by itself, receiving close to no support from the Manipur state government. “People from our community are contributing every month, but we are about to finish a year of being at war. How long will we fend for ourselves?” asked Dr Grace. Many of the displaced, she explained, stay in these camps mainly because there are basic supplies, such as food, available at the camp. “Most of them are not even forthcoming to request even medical care; they are all feeling a sense of being a burden on society.”

Organisations such as the Kuki Students Organisation (KSO), despite exhausting its resources set up close to six temporary schools catering to more than 1000 students ensuring that these students did not lose out on formal education. The Highlanders Dream Project is a venture that seeks to serve as a bridge for educators in providing support to augment learning losses caused due to displacement. More than 1071 children are being catered to by 47 fellows spread across 47 relief camps. Jessica, who is a part of this initiative, shared that many of the children she interacts with worry about having to discontinue education, as their parents are not in a position to earn income. To hear that they have no resources for schooling is heartbreaking, but it is also a reality for these families, said Jessica. Jessica, on her part, has been identifying such children and negotiating with some schools to enrol them. “Though we are amidst chaos and are facing so many challenges, I am coming across people who are also pushing their limits to help each other. The children in these relief camps are full of dreams, and we need to do everything in our capacity to be their voice and get them closer to their aspirations.”

Organisations aside, there are also individuals who are going out of their way to ensure they provide for society in ways that would seem impossible.

To anyone who knows her, Tracy Kipgen would seem like someone who is always on the move. A teacher from the hill district of Kangpokpi, she runs a school with her husband. As the war resulted in widespread displacement, she felt that her calling was to facilitate access to education for internally displaced children. Since then, she has organised support for most internally displaced children in surrounding relief camps and for those who are in no position to pay for their children’s education.

Tracy along with internally displaced students studying at the makeshift school

Admissions underway at the newly built school

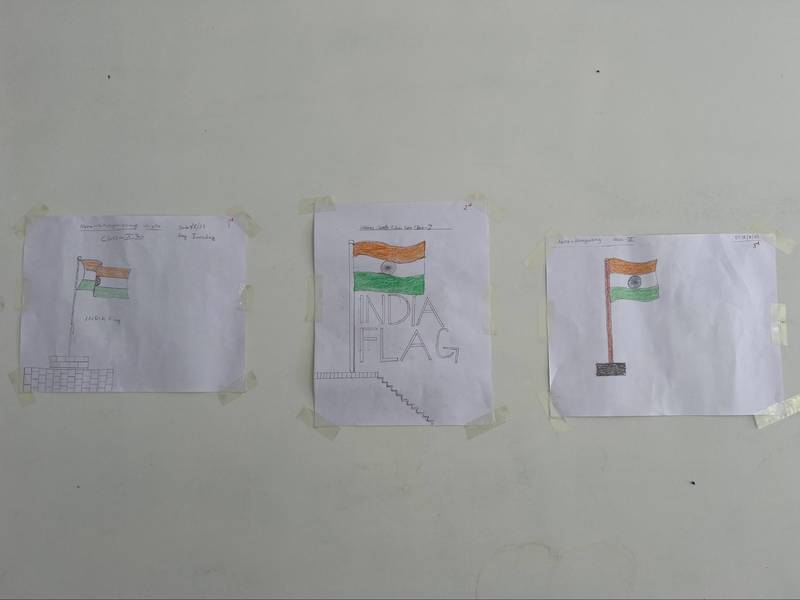

Student artwork: National flags drawn out by Kuki-Zo students on Independence Day

(L-R)Achong, along with her colleagues Siamkim, Julie and Jonathan at the school they’ve built themselves

I had first heard of Tracy from the Kuki-Zo journalist Kaybie Chongloi, who had informed me about an event she had organised to mark the 75th Independence Day of India. Tracy had accumulated resources to pay eight teachers, many of whom were themselves displaced, who were taking classes for children in their relief camps at a makeshift facility close by. On August 15, Tracy organised a drawing competition at this facility, where students had to depict the tricolour in the best way possible. When I visited the makeshift school, I saw drawings of the national flag along with the names of children and their villages written on them. All these villages were burnt down and now lie deserted in buffer zones. Yet, miles away, in a relief camp, the children of these villages were participating in an exercise to showcase their patriotism, even though the state to which they belonged had reduced them to ‘illegal immigrants’ or ‘narco-terrorists’. The weight of these images, drawn by students whose future has been rendered uncertain by the country’s political dispensation, seemed to bear down on everybody present there.

This make-shift facility was fully functional with regular classes till it had to be handed over to paramilitary forces in January. Undeterred, Tracy planned with the teachers to build a small facility alongside the relief camp. As she started raising money, she sourced materials that the teachers eventually used to build up the camp by themselves. By the time I visited the camp in February, the school had been fully built. The school’s principal, Neilemchong Suantak, showed me around the classrooms, all of which were built by her and her colleagues using their bare hands. Very young herself, Achong was displaced when her village came under heavy fire burning down her house. She told me that her older siblings are still at the periphery of her village, keeping guard. I felt compelled to ask her how she stays level-headed, steering a whole school by herself and managing children who are also affected by the same trauma that she was living with. The response was:

“Education is the greatest weapon we have. All of us have the responsibility of removing war from our society. Even during this violence, I want to help children in the best way possible, where I can teach them what is right and wrong. When they have the power to make these judgments and have good thoughts, our problems will see their logical end. We teachers have an important role. We need to show younger people the right way. They are our future.”

Reporters note:

I’ve been reporting from Manipur since June 2023. From the very beginning, I could understand that though women were contributing as much as men in facing the brunt of the war, their roles never received enough acknowledgement nor were their views taken into account while making important decisions. As an outsider, I could see that women leaders had a much more pragmatic method and manner of dealing with most situations, yet they found no place on the leadership table. This, I was made to understand, stems from a society that is founded on a patriarchal structure, yet a visible reluctance of present-day male-dominated organizations to relinquish space to women during a crucial time as this continues.