Ali Akbar Mehta (b. 1983, IN/FI) is a Transmedia artist, curator, researcher and writer. Through a research-based practice, he creates immersive cyber archives that map narratives of history, memory, and identity through a multifocal lens of violence, conflict, and trauma.

Close Watch exhibited at the National Finnish Pavilion at Venice Biennale, 2022, is a multimedia installation that, at its core, utilises the artist themself as an embodied intervention within a focused area of artistic research and apparent critique. In the context of this work presented as an exhibition at the national pavilion and its implications of somehow representing Finnish Art, this text seeks to question whether issues pertaining to embodiment and social intervention – and by extension, research conducted and artistic practice developed through it – can ever be free of the power relations implicit in the political, identity-driven understanding of society today.

Embodiments of privilege and extensions of precarity

Can the ability of the artist (as a white, middle / upper class body) to secure themselves a job and receive training within a security company, in order to carry out their process of artistic research be perceived as anything other than a striking signalling and affliction of privilege? Even if we ignore the fact that Takala occupied a position that likely could have allowed another candidate (in greater need) to potentially earn a living wage (and obtain funds to secure a year’s worth of living permission from MIGRI), it is impossible to deny that there exists some kind of perversion at the core of this situation: on one hand, an artist is structurally enabled by a system to enact a choice, to legitimately utilise a work opportunity as a means to conduct artistic research.

In contrast, hundreds if not thousands of art and cultural workers, competent beings who otherwise excel at what they do, are forced to devalue, let go of, or set aside their expertise, nevermind their desires and goals, to perform labour and work outside of their primary vocation and field of work. While it is difficult to find jobs to supplement an art and cultural practice, the field is saturated with “unpaid internships”1 that expect a bursting roster of ‘useful’ skills, low wages in their field of interest, language barriers, and wage disparities between Finnish and non-Finnish workers. Although “foreign-born unemployment is almost four times higher than the overall unemployment rate [and] immigrants earn, on average, 25% less2 than native-born Finns”3, a majority of non-Finnish art students who face these structural inequalities, permanently return to their home countries4 after being unable to secure basic living conditions for themselves. Those who believe that staying in precarious conditions is a better option than returning5, or those who are tenacious enough to stick with the task of creating a diverse art field in Finland, are almost always working multiple jobs, performing administrative tasks for their practice, and navigating a system6 that is designed to be more closed to outsiders than open.

It is especially in the context of a work exhibited at a platform such as the Venice Biennale, especially of it holding space in the ‘National Pavilion’ where national identities are being played out in the domain of art and culture, that questions of representation on national and transnational scales become a critical line of enquiry: At which stage do we define ‘we the people?’ “Who really are ‘the people? And what operation of discursive power circumscribes ‘the people’ at any given moment, and for what purpose?”7

Like any grouping, a ‘people’ are a contingent group. This means that any taxonomies that form the parameters of defining such a group are equally derived from an understanding of those ‘outside’ of it. For example, by saying that there exists a group of people who are X, a group is automatically created: those who are not X. Any attempt to define a group, a community, or a people, by default creates a process of othering; every contingent group creates another, comprising of those not included, of the other. When people attempt to answer the most basic question humans can face, ‘who are we?’, they are answering this question in the traditional way human beings have always answered it, by reference to what means most to them: in terms of ancestry, gender, religion, language, history, values, customs, and institutions; identifying with cultural groups, whether tribes, ethnic groups, religious communities, nations, and at the broadest level, civilizations. Things that provide the most stability are also perversely those concepts that resist change, and a systemic condition is generated where we know who we are only when we know who we are not, and often only when we know whom we are against. We are in a world that has created new levels of precarity, where the most important distinctions among peoples are not only ideological, social, political, or economic, but a potent mix containing all of these ingredients – they are cultural. One’s choice, if it were possible to make such a choice, would ideally be dependent on one’s own comfort with the level of contingency – at which stage do we choose to exclude? If membership is an inevitable act of exclusion, then any kind of a delineation of a ‘people’, is a “status symbol.”8

This line of critique is aimed at Close Watch as a project and at Pilvi Takala as they are implicated as an artist present(ed) in the pavilion, and now representing Finland. However, through this text, I take the opportunity to say that the structural inequalities that give birth to projects such as Close Watch are generated through infrastructural apathy, and as such, this critique is also placed squarely on the proverbial shoulders of this infrastructure: of institutional bodies tasked with the ‘governance’ of art and culture; their choice to take seemingly ‘apolitical’ positions; whose stable income positions have been dominated by white Finnish workers, without even isolated solitary examples of people of colour (POC) occupying leadership positions; that forces upon the Finnish scene, a dissonance where institutional policy regulations are made and enacted by those who do not fall under the purview of such policies, on behalf of, and affecting those who are not in positions to contest such regulation9.

The idea that the Finnish art and cultural space is ‘a system that is designed to be more closed to outsiders than open’ is an important analogy to keep in mind when critically unpacking a work on security and power. For this, it may be useful to think through Achille Mbembe, who has written “[w]herever we look, the drive is towards enclosure, or in any case an intensification of the dialects of territorialisation and deterritorialisation, a dialectics of opening and closure. The belief that the world would be safer, if only risks, ambiguity and uncertainty could be controlled and if only identities could be fixed once and for all, is gaining momentum. Risk management techniques are increasingly becoming a means to govern mobilities. In particular, the extent to which the biometric border is extending into multiple realms, not only of social life but also of the body, the body that is not mine.”10

I. Structural issues: power, gaze and field

Close Watch, by Pilvi Takala, curated by Christina Li, and commissioned by Frame Contemporary Art Finland, is an installation housed at the Finnish National Pavilion. The commission comprises a multi-channel video installation, website http://closewatch.site and publication (at the time unavailable to the public). The space itself is designed to mirror ‘transgressional dynamics’ with the installation of a one-way police mirror that divides the interior. The multi-channel video is the pivotal element of the project. While the project is articulated as being “based on Takala’s experience in the private security industry, where she worked covertly as a fully qualified security guard for Securitas […]”11, it is perhaps important to clarify certain concepts.

In Ethical Covert Research, Paul Spicker writes that “the identification here of covert research with deception is very common (see e.g. Bulmer, 1982; Homan, 1991; Herrera, 1999) […] Covert research is research which is not disclosed to the subject – where the researcher does not reveal that research is taking place.”12 It is covert research, for example, “if a researcher simply stands and watches what people are doing, like checking whether motorists are using mobile phones.”13 similarly, a bystander observing an accident who decides to record and upload the video, or a journalist watching a football match who writes an article may both be considered covert researchers; or even myself as a member of an audience who, having observed the exhibition, decides to write this text are all examples of ‘covert research’.

Covert or sting operations have a long and contentious history of use within police and government, where legal and constitutional mechanisms justify or direct their use. Journalism is another field where covert research is conducted, although this history is also complex where its legalities are highly debated.14 The code of ethics inscribed by the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), a nearly-universal standard employed by news organizations with an interest in maintaining well-defined ethical principles, is made up of four basic principles indispensable to any ethical journalistic practice and professional lifestyle. They are: (1) Seek Truth and Report It, (2) Minimize Harm, (3) Act Independently, and (4) Be Accountable.15 16

For Spicker, “[t]he term “limited disclosure”, favoured by the Australian NHMRC, helps to make two points about covert action. The first is that disclosure is a positive act; a researcher may not actively be concealing the research, but unless there are steps taken to disclose what is happening, the activity may still be considered covert. The second is that disclosure is not a dichotomous concept, something that is done or not done, but a spectrum of activity: researchers can reveal nothing, a little, or a lot, and still not be making a full disclosure.17 As many writers have recognised, overt research often has covert elements.

“Deception, by contrast, occurs where the nature of a researcher’s action is misrepresented to the research subject. This can be done at the same time as covert work, but deception is not necessarily, or even usually, done in the form of covert research. Researchers who engage in deception mainly say they are doing one thing when they are actually doing another.”18 In other words, while some deceptive research is covert, most is not. For me, it is in this category that Takala’s research practice for Close Watch may be said to be situated.

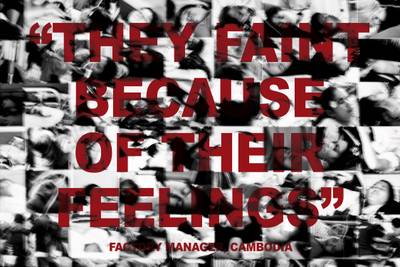

Another field performing both covert and deceptive fieldwork, with its own contentious history, has been the field of sociology19 and artistic research practises based on often dated conceptions of knowledge production that are appropriative and exploitative20. Close Watch deploys several ethnographic methodologies, familiar to those operating within the spheres of urban anthropology and human geography. Can “[g]oing undercover to infiltrate communities and disrupting social equilibrium”21 be done without an implicit awareness of the relational dynamics of power between the observer (here the artist) and the observed? What are the ethical implications of the artist’s deception towards their fellow workers? Must these workers be placed on trial in the socially voyeuristic gaze of an international audience at the Venice Biennale, or elsewhere? Perhaps the questions that really need to be asked, are ‘Who is really surveilling who? Who is observed, judged and policed? To what end?’

What are the ethical implications of the artist’s deception towards their fellow workers? Must these workers be placed on trial in the socially voyeuristic gaze of an international audience at the Venice Biennale, or elsewhere? Perhaps the questions that really need to be asked, are ‘who is really surveilling who? Who is observed, judged and policed? To what end?’

Another key distinction lies between ‘research participants’ and ‘research subjects’. It is important to note that this ‘deception’ is carefully designed: while the artist’s co-workers (research subjects) were unaware of the artist’s intentions and motivations, specific members of Securitas’s managerial team (as research participants) were aware of who ‘Johanna Takala’ (the artist’s alias) was, and her motivations during the six month period of employment. The artist has shown herself as being in regular communication with her contact Kari Holmström22, a security manager at Securitas for over 30 years, who not only facilitated Takala’s employment but also ensured the safety of the artist during this operation.

It is in this, the artist’s mutually consensual and ‘cordial’ relationship with Securitas, and of selective covertness in relation to fellow security guards, that create for me a skewed constellation of power. And this constellation is visible in the fact that while the security guards as individuals are the object of critique, the company as an institutional structure that generates and imbues these individuals with ‘authoritarian power’ are not. In the wide spectrum of a global corporation23 spanning multiple countries, a dense hierarchy of legislative power structures, and a global workforce of 355 000 employees24, the focus is on the most precarious, on-ground staff, within one. single. shopping mall.

Is this an acceptable gaze of artistic research? In Artistic Research as Institutional Practice, Esa Kirkkopelto forwards an argument that the dilemmas formerly related to ‘institutional critique’ practised by artists have now been removed within academia, and marks a change and/or shift of “the medium of making and action itself: an artist changes her artistic medium into a medium of research”.25 This shift is noted to take place within academic settings, and also within the field “primarily because of academic settings,”26 giving birth to the agency of the artistic-researcher. Specifically elaborating upon the triad of ‘innovation, invention, and institutions’ within capitalist (university) frameworks, Kirkkapelto’s claims that “artistic research not only takes place in institutions, but it should also conduct research on them”. Such a claim corresponds to Holert’s cautions against the current institutionalisation of Artistic Research, that Artistic Research can hardly be viewed in a ‘value-free’ manner. It is linked all too closely to the concept of knowledge as a utilitarian tool – aiding the production of economies within present capitalist orders – for it not to be questioned. Within ‘institutional practice’, the concept of knowledge is fortified through multiple iterations, and this way institutionalised as ‘politics of knowledge’, ‘knowledge economies’, and ‘power-knowledge relations’ as ‘a productive force’ for biopolitical expansion. In their scathing critique of Documenta 13, Manifesta 9, and the seventh Berlin Biennale, artists Alice Creischer and Andreas Siekmann proclaimed that because any “critique” of capitalism pursued by artists, curators, and theorists is usually spawned within the contemporary bourgeoisie (and therefore remains firmly grounded in the art world as we know it), such critique is not capable of bringing about structural political change “but is first and foremost a question of the political ethics of each individual protagonist.”27

Can the position of the artist as a researcher, and her team of professional actors and theatre pedagogues, create a space free of their own subjective positions of expertise? Can such positions be made equal, and were they? Can researchers become invested in sharing positions of vulnerability they seek to generate in the participants? Does the researcher’s role, and their agenda of extracting data (here stories and experiences), separate them from the positionality of the participants?

The exhibition essay on the project website closes with a statement: “Close Watch reflects on how control is enforced, and shows that it is we, and no one else, who govern each other’s behaviour” [emphasis mine]. Can this be understood as an accurate descriptor of the work? Can we say that it is ‘we who are ultimately governing each others’ behaviour’28 29, while being in the presence of such a clear power hierarchy? Who is the ‘we’ whose agency is claimed?

Can the position of the artist as a researcher, and her team of professional actors and theatre pedagogues, create a space free of their own subjective positions of expertise? Can such positions be made equal, and were they? Can researchers become invested in sharing positions of vulnerability they seek to generate in the participants? Does the researcher’s role, and their agenda of extracting data (here stories and experiences), separate them from the positionality of the participants?

What does it mean for an artist to perform such a covert operation, to perform critique in the limited form of reducing itself as an exemplifier of security through a handful of complicit bodies, to extend a claim that the only forms of aggression relevant to the project’s scope of enquiry were the direct and tangible acts of violence the artist witnessed?

It is perfectly understandable that through and due to extended timelines of the research process, the artist bypasses the ways in which security guards are encountered by the public, and instead faces them as colleagues, acquaintances, and peers. In the video, it is clear that the sympathies of the artist are with the security guards, but it is unsettling that broader questions of solidarity and support remain limited to the closed group as a closed ecosystem and echo chamber, where it is the body of the aggressor that is prioritised, coached in how to deal with such aggression, and strategies are developed to circumvent and diffuse this body’s aggression. Furthermore, in dealing with security guards as ‘compromised bodies’ who are asked to evaluate their own culpability in the on-the-job excessive use of force, racist language and toxic behaviour, is it not troubling to not find in the process a single qualified person who may actually bring the toolkit required for the safer space required for an effective assessment? The project’s text declares that the artist worked as a ‘fully qualified security guard’, but is the artist or anyone in the team also a fully qualified social service worker, psychoanalyst, therapist, or any kind of professional with experience in handling such potentially difficult dialogues?

On the other hand, the party that apparently faced the aggression is again made invisible in the work. The ‘Being Black in the EU (siirryt toiseen palveluun) report’, cites Finland as having the highest rate of racist violence, including assault by police (14%); the highest rate of racist harassment (63%); 31% of its participants experienced racial profiling; 61% of hate crimes were were conducted by individuals from non-minority backgrounds, and an overwhelming 86% of cases went unreported30. Why are these voices missing from the dialogue in Close Watch?

What does such an omission in a project dealing with civic liberties and social injustices, sediment as an artistic practice and an artistic gaze? What kind of value of critique does it generate if it limits itself to being concerned with a closed ecosystem, to effectively become devoid of critiquing security in its broader contexts: the structural and cultural forms of violence embedded in the very nature of enforcement, both in its physical embodied form, as well as pertaining to techno-legal infrastructures, formulation of protocols and policy, and the hyper normalisation of what is tolerable (by whom)?

It is difficult to not imagine alternate scenarios, to wonder what the tone of the project would have been if Takala had not sought employment through the knowledge and consent of management; if the on-job artistic research were conducted in conditions of precarity as opposed to in collusion with the authority of the artist’s employers; what if it was her fellow security workers who were ‘in the know’ and the company was ignorant of her covert workings, could there have been more visible signs of speaking truth to power, of institutional critique?

In this sense, it is difficult to not question, what is really the aim of the work, at least in relation to these security guards as participants? Is it to provide sensitivity training, through DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) discourse? Could such an interventionist model of the project, at least articulate for the security guards an umbrella of socio-political constructions of everyday racism, whiteness, and critical diversity? Could it facilitate techniques that allow them to divest themselves from positions of ‘oppressive’ authority carriers? Can such a process serve as a template, inviting reformation of how security guards themselves approach public spaces differently, to create an “encounter of equals”31?

Misanthropic scepticism provides the basis for the preferential option, which explains why security for some can conceivably be obtained at the expense of the lives of others. The imperial attitude promotes a fundamentally genocidal attitude with respect to colonised and racialized people. Through it, colonial and racial subjects are designated as disposable. Today, this disposibility is visible at its highest levels in ways that biopolitical relationship are configured on the premise that the right to life, which is secured by governments for those whom they are responsible for, such as their citizens, is based on the question of who is disposable, those who are not citizens, and those whom they may ‘let die’.

But I am more interested in the ‘field’: as the site of governance, in as much as governance has been reduced to the role of ‘management of risk’, where “the image of piloting, that is to say, management, has become the cardinal metaphor to describe not only politics but all of human activity as well.”32 Who is the ‘we’ in these public spaces: is it the security guards, or those being managed? Are the latter a homogeneous entity? If not what tags, markers, or politics of identity are employed by the security guards to profile, assess, and engage? Along with the need for collegial solidarity, are these also learnt ‘on-the-job’? Or part of the compulsory training? What are the structural methods of learning that cement cognitive biases? What dictates levels of threat? What goes into the creation of these training modules, sensitivity or apathy? Are these biases that make themselves visible as racist humour and toxic masculinity, present due to a high-pressure job, or a more deep-seated mental construction of the social orders of our society?

In his text Coloniality of Being (2007), Nelson Maldonado-Torres contends that what was born in the sixteenth century was something more pervasive and subtle than what at first appears in the concept of race: an attitude characterised by a permanent suspicion that is central to European modernity. Torres claims that “[s]cepticism becomes the means to reach certainty and provide a solid foundation to the self.”33 He names this idea of coloniality ‘Manichean Misanthropic Scepticism’, a method that generates ‘doubt’ in a way that is most obvious, describing it as “a worm at the very heart of modernity.”34 Through it, statements of fact are replaced by cynical rhetorical questions: ‘you are a human’ become ‘are you completely human?’; ‘you have rights’ becomes ‘why do you think that you have rights?’; and ‘you are a rational being’ takes the form of the question ‘are you really rational?’

The instrumental rationality that operates within the logic that misanthropic scepticism helped to establish, are the reasons why ‘progress’ always means progress for a few, and why Human Rights do not apply equally to all, among many other apparent contradictions. Misanthropic scepticism provides the basis for the preferential option, which explains why security for some can conceivably be obtained at the expense of the lives of others. The imperial attitude promotes a fundamentally genocidal attitude with respect to colonised and racialized people. Through it, colonial and racial subjects are designated as disposable. Today, this disposibility is visible at its highest levels in ways that biopolitical relationship are configured on the premise that the right to life, which is secured by governments for those whom they are responsible for, such as their citizens, is based on the question of who is disposable, those who are not citizens, and those whom they may ‘let die’ (Mbembe: 2019)35. Disposibility then becomes not simply a flaw or an error, but a key feature of security and governance today.

To refer back to the first section of this text, where I sought to highlight the levels of precarity that have become the burden of marginalised peoples in Finland, it cannot be omitted that for many of these bodies, the contestation of identities is not between consumer and citizen, but whether such bodies are even considered to be ‘citizen’. In the case of foreign-born professionals and immigrants, the fitness of non-citizens is judged entirely on the basis of economic value, where the sole significant criteria is an open-ended contract. Does such a configuration of economic fitness and management of the ‘right to live’ render the difference between consumer and citizen irrelevant? In this case, do all immigrant bodies become reluctant consumers of the state? Does the state itself become a market? How then, would comparisons of the mall and the state, as sites of consumption, work within the context of Close Watch?

Generally speaking, and also within the context of the project, it is clear that interactions between security guards and those policed are not innocent. There is no sugarcoating the fact that in the social dynamics at play when two bodies (to use a crash-and-burn terminology) collide36, are not neutral. Let’s make no mistake, these are not benign nor desirable interactions: at the moment of the encounter, both parties are wary, guarded, view the other as hostile and capable of unexpected violence. In these scenarios, one party is vested with authoritative power: freedom granted by one in authority, and the other already a subject of marginalisation, imbued with an authority bias, expected to be compliant, or otherwise considered volatile and requiring to be made submissive, even through force. These encounters transform the ‘field’ into performative sites of reinforcement, reproduction, and intensification of vulnerability for stigmatized and dishonoured groups. In such interactions, there is often no middle ground, no room for resistance.

For Marshall McLuhan, it is in the inherent “nature of the medium, of any and all media,”37 to be the amputation and extension of its own being in a new technical form, that no technology may shed its political nature – the tools of surveillance carry within them an inherent nature to generate its position of power. Travelling back into the timeline of surveillance, we can see that “eighteenth-century records of criminal justice rarely record any more information about the criminal than their name […] by the mid-nineteenth century detailed records were kept about their age, physical characteristics, education and religion, family and previous convictions, together with judgements about their ‘character’. This information was all routinely collected long before it was consolidated into the 1869 Habitual Offenders Act and it presages the better-known late-nineteenth-century introduction of photography and fingerprinting.”38

Today, the conditions of the ‘field’ are much more complex. With biometrics, retinal scans, genetic tests, personal identifiers fed into credit cards, passports and other ‘verified papers’, surveillance capitalism has become the key marker that defines civilisations as ‘modern’, where personal experiences and knowledge production are both shaped by and through surveillance. Are security guards reduced to embodied tech, already cyborgean manifestations of surveillance systems, their own humanity simply a ghost in the machine?

II. Failure of imagination

As I hope to have clarified through this limited line of questioning, a complex set of performative reiterations ossify into forms of regulation and standardisation, affecting behavioural norms between those policing and those being policed, especially in a global post-landscape of the recent contestations of police brutality, state-led policing as means to restrict human rights, and the questioning of citizenship as a practice of governance; especially in Finland given the privatisation of state-held law enforcement.

What Close Watch as a project on security – as a relationship to bodies with power and authority to enforce behaviour in public spaces – fails to put forward is a “counter vision”39, where working together may “envisage the creation of a vibrant ‘agonistic’ ‘political public sphere’ of contestation where different hegemonic political projects can be confronted.”40 No doubt, Close Watch is an exercise in public pedagogy, but how is it a public practice, and for which publics? How does it generate or engage with a new publics? How does it help its participants and its audience locate the ‘outside’?

For me, the promise of a research that finds ways to ‘profile the profilers’, to ‘police the police’ and to ‘perform surveillance on bodies that routinely conduct surveillance’ within the given politicality and socio-activist drivers of the art field, are already strong concepts that can potentially serve as potential drivers for utopian change. While the project recognises that in Finland, “[m]uch of state-held law enforcement is relegated to the private sector, representing a thriving and largely underregulated global industry”, it does not seem to be interested in the specifics of such underregulations, nor its implications on the public. Furthermore, considering the global urgency of defunding police, the critique of western incarceration systems, and the nature of its relevant fieldwork, what are the implications of the discourse offered by Close Watch that focuses on the security guards, rather than the structure that enables them?

For a project commissioned especially to be exhibited in a transnational platform such as a biennale, I would hope for it to provide atleast an effective beginning to unpack such issues, comprising greater depth of research seeking to investigate the production, representation and application of power within the domain of the security industry, as it focuses on ground-level manifestations and enforcement of power. At its outset, such framing and research would be necessary not only in order to understand how manifestations of power within authority carriers are actualised, but on whom (what people, and which culture) is such actualisation directed. In this sense, work that centres the survivors of legalised policing is crucial. Unfortunately, neither is such a critical gaze visible in the work, nor perhaps would it be appreciated coming from a white body.

This is not to say that questions of security, surveillance, embodied extractivism, and the right to speak against marginalisation produced by these, are the sole domain of queer, trans, or BIPOC bodies, but that there is something of value in prioritizing the voices and experiences of those who are routinely racialised, segregated, marginalised and othered, where such experience becomes infused into their core in ways that are often incomprehensible to privileged bodies. Although I am a member of a group of people that is, for example, ‘randomly’ checked, on whose person and property regular explosive and/or narcotic tests are conducted in airports; who is often heckled by drunk men who threateningly brandish beer bottles or cycle chains as amused security guards look on; who upon approaching on-site police during ‘permitted’ protests to report racist behaviour is told that investigating this is not part of their scope of work, and is victim-blamed for being present; or whose experience at MIGRI or other spaces of management has taught him that knowledge of one’s own self is secondary to the authority’s knowledge of you. Although I am a member of such a group, I cannot tell you what modes and intensities of othering are faced, for example by the Sámi, the Roma, Afro-Finns, immigrant workers, queer*trans communities, and asylum-seekers. I cannot speak for them, hold space for them, nor create platforms. What I can do is support them as and how they choose to tell their story; what I can say is that any reasonable understanding and critical study of power relations in the context of security must begin here: by centering these voices.

“What distinguishes political from civil society is that the discourse of citizen’s rights must translate into a preemptive commitment to radical change”.41 This change is in the stark light of a reality where the rifts between power structures and the subjugated have not decreased; neither have the gaps between class distinctions. Rather, we are in a contemporary world that today has created new levels of precarity, the refugee class, and in contrast, a new kind of human beings, “the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends”.42 Perhaps only in denying the fundamental myth of operational power as being inherently benevolent, can it become possible to create new infrastructures and (knowledge) systems that may actively work to counter them. And so, a definite characteristic of the ‘political’ emerges where public spaces become “the battleground where different hegemonic projects are confronted, without any possibility of final reconciliation.”43 If public spaces are always plural and the agonistic confrontation takes place in a multiplicity of discursive surfaces, then can anger and frustration at structural inadequacies be a legitimate emotional response when viewing a work? If research is not a prerogative of research institutions, but is the prerogative of living life’, can my own position as a ‘brown’ ‘immigrant’ artist become a valid counterpoint to the gaps I perceive in the criticality of an artistic research project? Can yours?