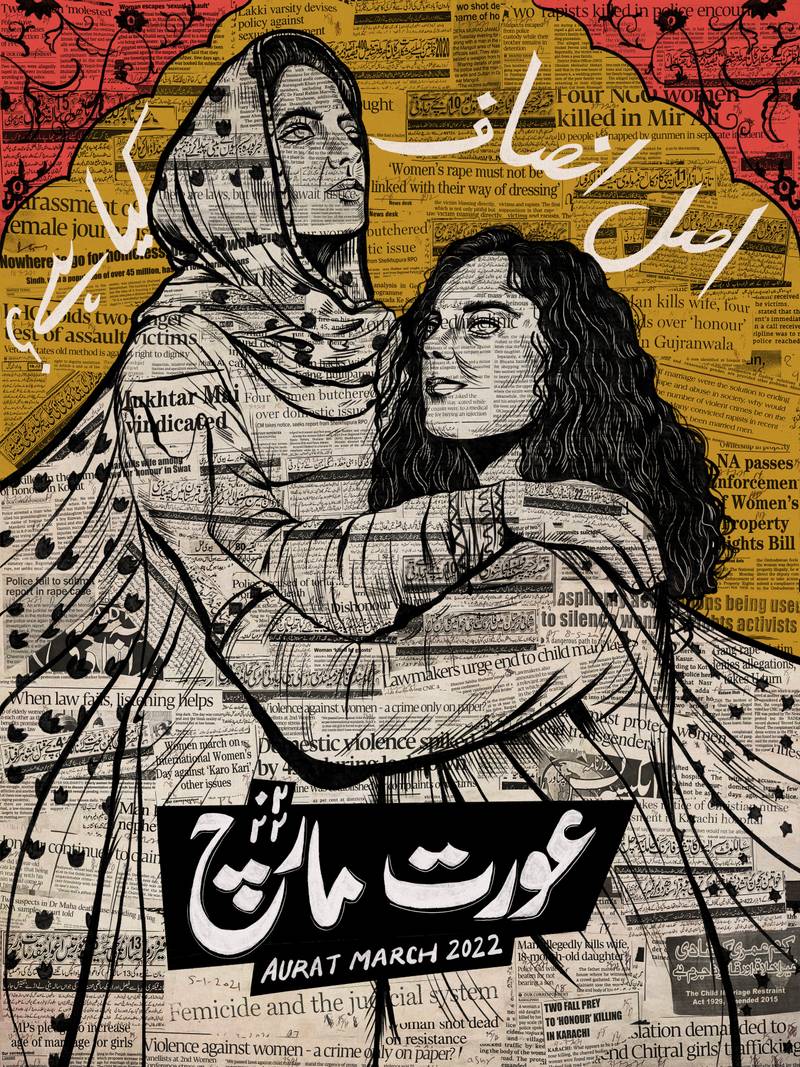

Poster: Shehzil Malik

Hira Azmat is a storyteller, editor, and a Pushcart Prize nominated poet. She has been working in the cultural industries in Pakistan for the last 12 years; her professional experience includes working as a curator of cultural spaces, and as an international arts manager. She is interested in arts and culture, movements and subcultures, literary criticism, and good design. She can be reached at hira.azmat@gmail.com.

The first marches took place in 2018 in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad - in a seemingly coordinated explosion of radical protest across the three main city centers on Women’s Day in Pakistan. Before that year, Women’s Day in Pakistan was a sedate little NGO-commemorated day on which development professionals talked at representatives of the sitting government about SDGs and worrying statistics. Or it was marked by government-sponsored tokenistic ad campaigns about non-controversial high-achieving women.

This changed in 2018 when three Aurat March chapters across different cities - ostensibly non-hierarchical, avowedly self-funded - announced their Aurat Marches in their respective cities. There was an effusion of radical feminist digital art and hashtags, fiery debate and declarations, and mobilization on the streets, including street art murals, posters and solidarity building with working-class women’s organisations and marginalized communities. That first year, the marchers were modest in number, but the idea of women marching, singing, dancing, shouting on the streets that were otherwise hostile to them every other day of the year had an extraordinary impact. Pakistanis sat up and paid attention - but that wasn’t necessarily a good thing. The march has happened every year since and has spread to smaller cities, including Peshawar, Quetta, Multan, Faisalabad, Hyderabad and Sukkur. And the backlash against it from mainstream media, government institutions, and religious militant organizations has continued to escalate and exponentially exceed its own scale.

Pakistan is ranked 153 out of 156 nations in the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Report - the only countries ranked lower are Iraq, Yemen and Afghanistan. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, 90% of women have experienced some form of domestic violence at the hands of their husbands or families; 47% of married women have experienced sexual abuse, including rape. According to the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Pakistan is the sixth most dangerous country in the world for women. Women make up merely 22% of the (paid) labor force and receive 18% of the country’s labor revenue.

The Aurat March was hardly born in a vacuum; Pakistan has a significant history of feminist resistance. Galvanized by military dictator General Zia’s Islamisation laws and deeply conservative cultural impact, the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) was founded in 1981 by 15 women. Images from WAF’s iconic protest against the Hudood Ordinance, which infamously sought to reduce a woman’s legal testimony to half of a man’s, became synonymous with the Pakistani feminist movement for decades. Since then, though, the culture of visible feminist protest seemed to have petered out, barring small leftist groups and indigenous movements that did not garner much attention. The NGOisation of feminist political action and an approach primarily centered on legal reform became the movement’s most salient features. Then, the 2010s saw a mushrooming of smaller feminist collectives such as ‘Girls at Dhabas’ - a protest group centered around reclaiming public space for women - emerge, and these small groups, divorced from their spiritual predecessors in many ways, eventually culminated in the Aurat March.

Dr. Rubina Saigol, an eminent Pakistani feminist scholar, identifies AM organisers and participants as the fourth wave of the Pakistani feminist movement. She writes in Contradictions and Ambiguities of Feminism in Pakistan: Exploring the Fourth Wave that what differentiates these new feminists from older local feminists is that beyond demanding equal rights, they also seek to challenge the private spheres of life where patriarchy prevails. Dr. Saigol describes their refusal to be respectable and their insistence on defamiliarizing the intimate and holding it up for scrutiny in public spaces as a “tectonic shift”. According to her, this current fourth wave is “challenging and deconstructing the hallowed private sphere of the family, community, and society”, as well as mainstreaming marginalised/alternative gender identities and sexual expression.

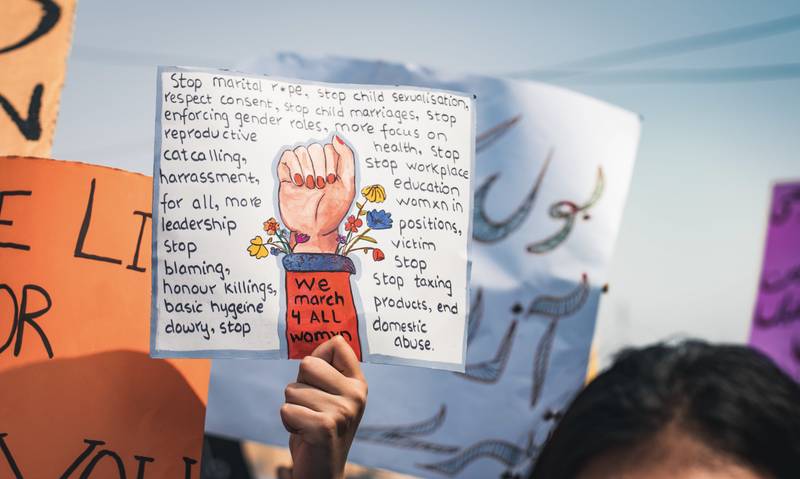

Photo: Umar Riaz

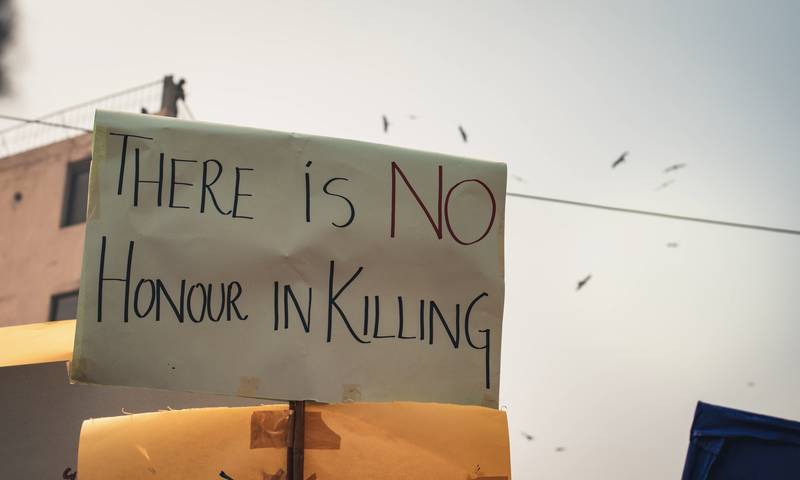

Photo: Umar Riaz

What specifically caught public attention at the first Aurat Marches across the country were the signs held by protestors; organizers encouraged protestors to bring their own. Most signs were unique, hand-made, and expressed the individual protestor’s rage, plea, or wit. They ranged from plaintive to irreverent and covered wide-ranging issues such as property rights, maternal health, the right to public spaces, equal pay, and educational opportunities for girls. However, it was a handful of signs that went viral online and have done so every year since: “mera jism meri marzi” (i.e. my body, my choice), “lo main beth gayi sahi se” (i.e. look, I’m sitting properly now, with an illustration of a woman sitting with her legs comfortably apart), “divorced and happy”, and “khana khud garam kar lo” (heat your food yourself), an allusion to the additional domestic labor of serving men that often falls to women in local households.

The backlash was swift and multi-pronged. In the immediate aftermath of the first march, concerted right-wing social media campaigns designed to go viral with photos and videos of participants with provocative commentary; anti-Aurat March hashtags pushed through bot farms would trend for days. The comment sections were rife with death and rape threats from men toward the protestors. Aurat March was portrayed as a significant threat to family values and public morality. It was accused of being propped up by “foreign funding” from nefarious external forces from Western governments to the “Jewish lobby”, and that messaging soon found its way to mainstream media. March organizers were invited to talk shows on national TV and put on panels alongside virulent misogynists such as the highly popular TV drama writer Khalil ur Rehman Qamar or conservative televangelists such as Amir Liaqat for the sake of creating viral content and high ratings. Subsequent years saw male journalists harassing protestors at the marches and making inflammatory comments just to record reaction videos in order to portray the participants as irrational, angry or debauched.

Unfortunately, while the most violent threats certainly come from external sources, internal conflicts have often threatened to implode this movement as well. One would imagine that such virulent opposition may foster unity within the movement in the face of common enemies. However, that has not been borne out in reality. A common public misconception is that the Aurat March is a monolithic entity with a single agenda.

The religious rightwing jumped on the bandwagon, of course, and escalated threats to the personal safety of the marchers with counter-marches. In 2020, for example, women from the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), JUI-F, Lal Masjid and female students of various seminaries staged the Haya March (Modesty March) in Islamabad, which turned violent as they chanted slogans, hurled stones and batons at Aurat March protestors. Similarly, a counter-march has been organized by the fundamental Islamist organization Ahl-e-Hadees in Lahore that threatens to spill into violence each year. Hordes of angry men threaten AM participants, alleging in their chants and placards that these are shameless women who want to spread sin and discord, break apart family structures and existing hierarchies - all that is deemed good, moral and respectable in Pakistani society.

It is evident that the state, or at least salient elements of it, has been complicit in this hate campaign against the Aurat March. Imran Khan, chief of the ruling party and Prime Minister of the country from August 2018 to April 2022, has described feminism as “a Western concept” that has “degraded the role of the mother”, implying it has no place in Pakistani society. He has also frequently decried “vulgarity” in society, a shorthand for women dressing beyond strict rules of Islamic modesty as well as sexual freedom and choice, and claimed it is the cause of the sexual violence epidemic in Pakistan. In March 2020, Khan singled out Aurat March as an example of social division and insisted that such “distinct cultures” needed to be rooted out to unify the nation. In 2022, the PTI govt’s Minister of Religious Affairs, Noorul Haq Qadri, appealed to then Prime Minister Khan to declare the UN-designated Women’s Day as Hijab Day instead, arguing in his letter to the PM that the Aurat March goes “against the principles of Islam”, “hurts the sentiments of Muslims” and that his letter reflects “the collective thinking of Pakistani society”. With such hostile rhetoric directed from the highest echelons of political and social power, it is no wonder that it emboldened other segments of society to continue their hate campaigns against AM. Over the years, organizers and participants have received thousands of rape and death threats, both online and offline. They have been widely referred to as prostitutes and whores, including in mainstream national media.

Photo: Javaria Waseem

Photo: Javaria Waseem

Additionally, the state has frequently seemed to create logistical hurdles for Aurat March organizers. It is a matter of public record that in various cities in different years, the Aurat March has failed to get a No Objection Certificate (NOC) till the eleventh hour and has had to resort to legal petitions to obtain it; issued by the city administration, an NOC is a requirement for organized protest and indicates that the administration accepts responsibility for safeguarding protestors. Most damningly, in individual interviews, multiple Aurat March organizers in different cities, who prefer to remain anonymous, have alleged that they have faced harassment by security agencies, who have threatened them in phone calls, arrived at their homes and intimidated their families, in a bid to get them to stop.

However, the ultimate threat to Aurat March came in the form of blasphemy allegations in 2021 against the Aurat March chapter in Islamabad, appearing to be based on clearly doctored images and videos. There are strict blasphemy laws in the country, but prosecution on that basis isn’t the only threat. Merely an allegation of blasphemy can cause vigilante killings or mob-driven violence - even a sitting Governor and a Minister of State have fallen victim to it in the past. So this became a potentially life-threatening situation, not simply for organizers but for the hundreds of women who participated. The charges were ultimately dismissed in two different courts.

The impact on the lives of the organizers of AM has often been devastating. An Islamabad-based Aurat March organizer, who prefers to remain anonymous, shares her experiences: “[Because of my work with Aurat March], in 2020, I lost my job, I lost my home – I still can’t find a job… and I’m not the only one who faced this kind of precarity. People don’t want their workplaces to know about their political activism. Right-wingers routinely tag organizers’ workplaces online [under their photos, videos and tweets] , which has threatened organizers’ livelihoods. Many women have to go through domestic violence to prevent them from going to Aurat March. Masjids condemn the Aurat March in Friday sermons. By 2021, nobody would even rent out the truck to us that we needed to put our banner on and use as a stage. The owner started beating up the driver for even asking. We couldn’t get fuel at petrol pumps because they would see our banner.”

Unfortunately, while the most violent threats certainly come from external sources, internal conflicts have often threatened to implode this movement as well. One would imagine that such virulent opposition may foster unity within the movement in the face of common enemies. However, that has not been borne out in reality. A common public misconception is that the Aurat March is a monolithic entity with a single agenda. However, in truth, each city has its own chapter, structure, and way of working. Each chapter sets its own manifesto and the theme for a particular year’s march, meaning there are multiple Äurat March themes each year. For example, Lahore may focus on labor rights for one year, while Karachi may focus on climate justice that same year. Since the March is entirely voluntary, organizers for each chapter may also vary from year to year. While all chapters espouse feminist politics, their political approaches and methodologies diverge significantly from each other, and that has caused its share of conflict, mutual distrust, and alienation.

The Islamabad chapter calls itself the Aurat Azadi March (Women’s Freedom March), a seemingly slight difference in name that not only highlights their political differences but has a history of hostility between the chapters. According to Islamabad organizers, the first March in Islamabad was planned without any involvement of other city chapters; it was a mere chance that they happened to coincide. Organized by women activists from the leftist Awami Workers Party (AWP), the first March in 2018 was, in fact, meant to be a commemorative event for the inception of their sister organization, Women Democratic Front. This organization was born out of a need for feminism that engaged with class issues and was a counterpoint to the dominant girlboss feminist discourse in the country. The leftist Awami Workers Party and trade unions joined what became the Women’s Democratic Front in 2017 and decided to commemorate its launch in Islamabad on Women’s Day - 8th March 2018. It is a leftist tradition that whenever a new political party is launched after the first congress, there is a commemorative public march open to the public. In the days leading up to the march, Islamabad organizers realized Lahore and Karachi were organizing a separate march led by women.

An ex-organizer from Karachi, who is not trans, elaborates on the subtle yet insidious ways this shows up in their organizing spaces: “Inclusion for AM is very performative. You are organizing together, but are you eating with them? Are you inviting them to your post-meeting chai sessions? Who are you partying with? Who are you including, then? That’s comradeship. There needs to be love in practice with each other. And it’s not just gender identity that creates barriers, but also class.”

In March 2018, a few days before this inception march was going to take place in Islamabad, local organizers received a call from the Karachi chapter from an organizer they didn’t know. During this call, they were told they couldn’t call their march Aurat March because that’s what Karachi calls their march. Since the march in Islamabad is associated with a political party (in this case, the AWP) which is against the modus operandi of the Karachi chapter, they couldn’t do it; it was referred to as a “branding issue”. Realizing it was too late to cancel their march, the Islamabad chapter scrambled to rename themselves and change all the event branding.

An ex-organizer for the Karachi chapter, who prefers to remain anonymous, reinforces that story: “There’s a lot of underhanded politics at play [between the chapters], and there’s this pressure for neutrality and diplomacy too…I think the Islamabad chapter, particularly, has massively borne the cost for all this. The other chapters have politically sidelined them for wanting to reimagine the platform and address the risks.” The Islamabad chapter positions itself as avowedly political, radical and socialist. According to an Islamabad organizer: “We wanted to deconstruct women empowerment versus women’s emancipation. Emancipation was more in line with our political vision.”

In addition to the inter-chapter tensions, there are also often tensions within each chapter. Reports of infighting within the Karachi chapter have been particularly frequent. Ex-organizers from Karachi describe an “arbitrary hierarchy” within the organizing space. They describe an environment of “lies and manipulation” and “of power being abused, people being ‘punished’ and isolated for having opinions that didn’t sit well with those with power.” Attempts made by some organizers to create a structure of accountability have been repeatedly thwarted. Many organizers have felt they faced punitive treatment for wanting the organization to move beyond “just a source of power and influence for a handful of gatekeepers.” One ex-organiser adds: “The problems we were citing - arbitrary hierarchy, bullying, abuse of power, no room for criticality or growth, were deeply political problems, but they were constantly presented as petty personal issues.”

Karachi-based trans activists, including Hina Baloch and Sana Ahmad, who have organized with Aurat March in the past, have publicly accused the chapter of tokenizing them - simply using their participation in order to appear inclusive while doing little to address their concerns within the organization or their struggles beyond it. An ex-organizer from Karachi, who is not trans, elaborates on the subtle yet insidious ways this shows up in their organizing spaces: “Inclusion for AM is very performative. You are organizing together, but are you eating with them? Are you inviting them to your post-meeting chai sessions? Who are you partying with? Who are you including, then? That’s comradeship. There needs to be love in practice with each other. And it’s not just gender identity that creates barriers, but also class.”

Aurat March organizers have faced hostility from older feminists as well. Some notable names have been supportive and have made an effort to engage with AM organizers, such as Dr. Rubina Saigol and Nighat Saeed Khan, as well as many veteran WAF members who attend the march each year. However, there are others who have been repeatedly dismissive or outright hostile. Some of the criticism sounds like standard respectability politics. The popular feminist poet Kishwar Naheed - ironically whose own poem ‘Hum Gunahgaar Aurtain’ (We Sinful Women) shot her to both literary fame and notoriety - has criticized AM participants for being too improper. Naheed said she disapproves of the slogans spotted at the march; she said she believes feminists should be keeping their culture and traditions in mind so as not to go astray like “jihadis”. Her own famous poem challenging patriarchal norms has often been quoted in placards at Aurat Marches across the country. Dr Afiya Shehrbano Zia, an established feminist academic, has frequently used her op-eds to write about AM. However, according to an AM organizer: “Each essay she writes seems to outdo the previous one in its lack of actual engagement with AM; she often gets her facts wrong and constructs a strawman to conveniently shoot down.”

Older feminists generally have a more reformist approach, believing in incremental change and engagement with the state to bring about change, and have criticized AM for not working with the state as a key site of political and cultural power. Aurat March organizers are often scathing in their criticism of that approach. An Islamabad-based organizer asserts: “Older feminists worked with the state to such an extent that they were co-opted by the state. Where did that get us? They didn’t leave the second line of leadership for us. For decades, there was no movement. Because they were so keen on engaging with the state, they forgot about building a movement and solidarity.” She describes AM’s approach toward the state: “Criticizing and confronting the state is also a form of engagement. We can’t just organize around the state; we must engage people first and then the state. We don’t work on legislation. I don’t think laws are particularly useful to women in this country. We have to operate like a group that forces the state to engage with us.”

Similarly, a Lahore-based organizer said: “Previous generations have focused on the state in terms of law reform; however, the state itself is very hostile and violent. Whenever we’ve engaged with the state, it has belittled and threatened us. Even at the march, there have been so many times that I’ve asked the police to help, and they have been indifferent–those interactions with the state have informed our politics. The state will always be what is in its best interest, and it will yield to law reform and other changes when there is a sufficient cost attached to not listening to us–so our focus is larger than the state at times. We do not look to the state as the ultimate site for liberation. That being said, the state is an important institution in society, and we engage with it. A lot of the demands in our charter each year are addressed to the state.”

Older feminists generally have a more reformist approach, believing in incremental change and engagement with the state to bring about change, and have criticized AM for not working with the state as a key site of political and cultural power. Aurat March organizers are often scathing in their criticism of that approach. An Islamabad-based organizer asserts: “Older feminists worked with the state to such an extent that they were co-opted by the state. Where did that get us? They didn’t leave the second line of leadership for us. For decades, there was no movement. Because they were so keen on engaging with the state, they forgot about building a movement and solidarity.”

The path forward for this movement must contend with a lot. Can the march overcome or at least develop strategies to circumvent the immense social backlash? Can individual chapters get their respective houses in order and work to build greater synergy with each other and become a sustainable, more ethical and inclusive force for change? Even an ex-organizer from Karachi, who has been disenchanted with the way things are run, refers to AM as “a real space of possibility”.

One of the default criticisms of AM, which is both partly valid and mostly lazy, is that it is a movement organized by elite women and is, therefore, about elite women’s issues. Their politics is irrelevant for the “real Pakistani woman”, now an oft-employed rhetorical device more than an actual person. AM is not the first feminist movement to face this criticism; WAF before them has historically received the same, but AM has done work to correct that structural issue - some chapters more than others. However, the leadership of all chapters remains in the hands of English-speaking, upper-middle-class women, indicating that much more needs to be done to make the movement more inclusive. An organizer based in Lahore says one of the movement’s biggest challenges that inhibit its growth is the pervasive disinformation and misinformation about its core purpose and the baggage attached to it. She says: “It has reached the point that its politics has been distorted beyond short-term repair. Many of the community-level organizing we do is severely affected by propaganda about the march; people are unwilling to either come to the march or support us despite the fact they will agree with us in person and during meetings.”

If you ask a random Pakistani, depending on where they stand ideologically, they will mostly either look to blame AM for all social ills or expect AM to be a panacea for all social ills, which is a frustrating catch-22 for organizers. A Multan-based organizer says: “We can’t be everything to everyone. Instead of tagging us under news about all social issues and expecting us to issue statements about every issue of the day or to resolve them, question your government. Hold them accountable. This is literally their job.”

One obvious way to ensure AM sustains its momentum and expands its vision is by growing it beyond an annual event where all energy is poured into it and instead becoming a more sustainable, year-round site of work. An Islamabad-based organizer agrees: “That energy needs to be put elsewhere. We need to develop women’s collectives that need to work consistently. People have to be conscious of their own oppression, but we need to move beyond affirmation; it should be about building an alternative. Or several alternatives. [We need] collectives everywhere in the country, not just the three big cities… People need more than what the march is offering right now.”

Aiman Rizvi, an ex-organizer from Karachi, agrees: “A march cannot fill up an entire movement; it’s on us to do the work of claiming space beyond that one day and one moment of collective protest.”

Another ex-organizer from Karachi takes issue with how limited AM has become even as a standalone protest event. “We need to reimagine intervention - about what it is to claim public spaces. Whatever the model was created in 2018 is still going on as a template – how does that differentiate between a regular political party jalsa and this? Reinvention is a regular part of a police state. Capitalism is ready to absorb anything you create and make it theirs. You have to keep rethinking and coming up with strategies they don’t expect. In Lahore, they hung clothes of women who had been sexually harassed – that was remarkable. In Islamabad, people pinned their hopes on a tree – and the innovative street art was something special. And this is how you build a movement. You don’t regurgitate. It then becomes a form of socially acceptable protest. What are you doing with all this power? The march is a performative space, and we need to think about what that performance looks like.”

Some ex-organizers for AM feel their labor is now better employed elsewhere. Aiman explains: “For me, the solution really lies in thinking and organizing beyond Aurat March. There’s a really big housing rights movement picking pace in Karachi right now, and the displacement that’s been unfolding is a feminist issue - and it’s an area in which you see direct state complicity and gendered violence. Those are the sites of protest that require our labor. Sometimes I feel like AM distracts and takes away from those issues because it has just ended up limiting our collective imagining of ‘feminist work’ and ‘feminist politics’.” Another organizer also cites other progressive movements in the country that deserve their attention and work, such as resisting enforced disappearances by the state, resistance to anti-encroachment drives in Islamabad, building solidarity with Shia Hazara activists, the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement, and the khawajasira (trans) resistance.

One obvious way to ensure AM sustains its momentum and expands its vision is by growing it beyond an annual event where all energy is poured into it and instead becoming a more sustainable, year-round site of work. An Islamabad-based organizer agrees: “That energy needs to be put elsewhere. We need to develop women’s collectives that need to work consistently. People have to be conscious of their own oppression, but we need to move beyond affirmation; it should be about building an alternative. Or several alternatives. [We need] collectives everywhere in the country, not just the three big cities… People need more than what the march is offering right now.”

Five years on, in the face of so much intimidation and violence, the gains from Aurat March are difficult to measure. An organizer from Karachi says, oddly reassuringly: “In this country, success isn’t always going to look traditional. Backlash should be seen as a diagnosis of how far the message is spreading. The loudest voices are always the angriest voices.”

What AM has made emphatically clear is that there are gender-specific issues in this country, and they must be an essential part of national political discourse. Tooba Syed, who has been an Islamabad organizer since the inception of the march, explains: “Even mainstream political parties cannot ignore [gender-specific issues] anymore. It was a very personal lived experience before, and it was through that lens that women saw their own problems, but this discussion of an entrenched patriarchal system that is in place and how it operates in our society in various spheres, public or private - that’s happened because of AM. We have worked very hard in opening up movements to working-class women and their issues – issues of land, housing, enforced disappearances, and inflation. It has also politicized the private realm – what happens in the private realm is no longer simply personal but a collective experience.”

Aurat March has been unprecedented in the way it has given Pakistani women both language and space to articulate their struggles. Tooba elaborates: “Women bringing their wounds to the city squares – I’ve never seen that type of dignified struggle in public spaces in Pakistan before. Before that, we only saw women being dragged out of their homes and beaten on the streets by patriarchs. The kind of role the institution of the family plays in society has become very visible because of AM.”

Aiman agrees and says it feels like “a small cultural shift.” She elaborates on what she finds hopeful about that change: “The ways in which our vocabulary has infiltrated cultural spaces, how the politics we represent are an active, ongoing conversation - the stories of those who feel empowered and emboldened by our visibilization of joy, power, and hope.” Due to necessity, AM organizing has largely taken place in digital spaces, which has had a pleasant side effect. “The digital community AM has helped foster is particularly remarkable. I feel like that community might have come to exist without the march, but how the movement was forced to operate and organize in digital spaces catalyzed the process. I’ve found so much solidarity, growth, community in these spaces - sometimes I’m able to be a version of myself I can’t be otherwise because of the solidarity I’ve found online and the community I’m able to access there.”

The way forward will require hope, imagination and bravado. An organizer from Lahore has a simple, optimistic vision of the future: “The march will be around for as long as people want to march and believe in its politics. The march means so much–it is a space for joy, expression, anger, and community… it will be around for a long, long time, I feel. We have to work on making sure it is accountable to the very people who march, and we live up to the political ideals we aspire to. If that fails, the march shouldn’t happen, no matter how many years it’s been. I hope the march can bring in more people who organize with feminist politics and more women willing to put in labour towards this politics. Perhaps we cannot dismantle patriarchy in our lifetimes, but we can chip away at it by creating more and more organizers.”

Photo: Umar Riaz

Photo: Umar Riaz

Photo: Umar Riaz

Photo: Umar Riaz

Photo: Javaria Waseem

Photo: Javaria Waseem