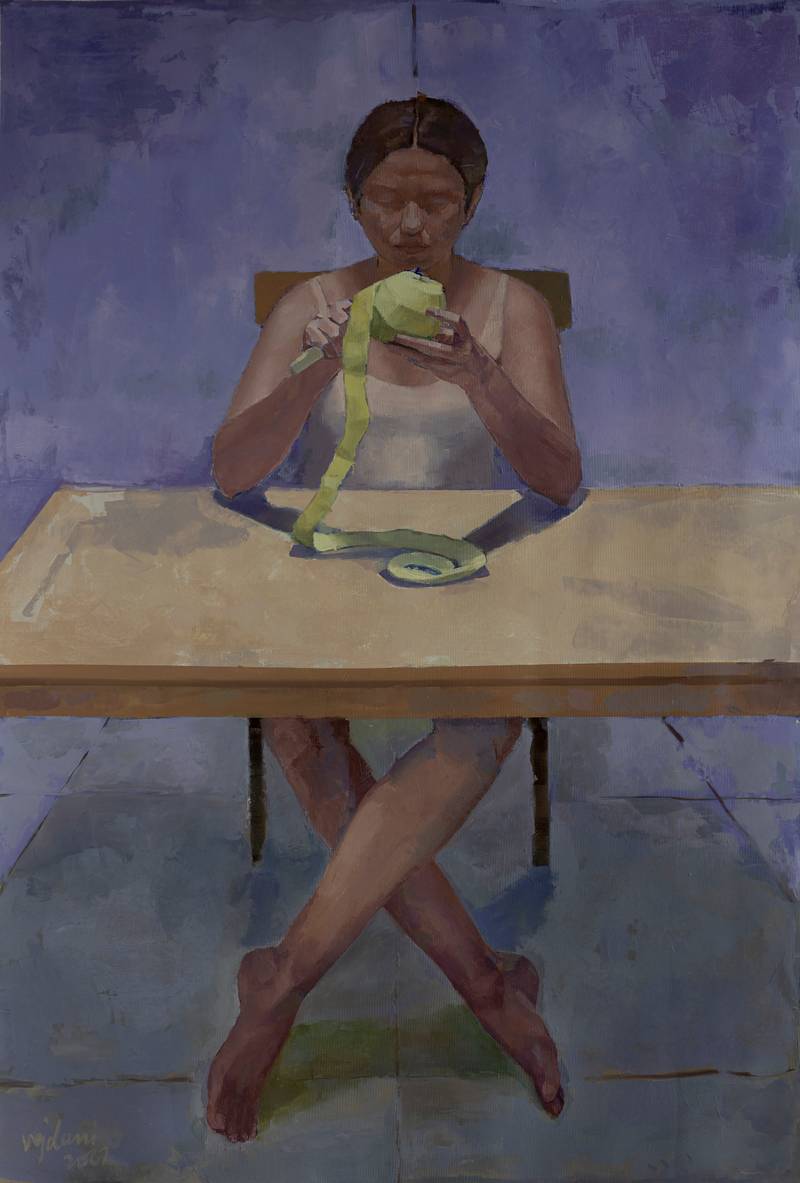

Memorial I, 2022, oil on canvas, 130 x 90 cm

Anna Ruth (MFA 1998) is a visual artist and art event organiser who has worked in Jyväskylä producing, directing and curating the projects: Äkkigalleria (nomadic art gallery since 2009), House Games triennial (2005–2017), Laatikkomo (2013–2019), ti-la2016, 100 Finnish Photographers, 2017 (curated by Hanna-Kaisa Hämäläinen & Markko Hämäläinen), and Tuokaa Tuoli! (a nomadic cinema in collaboration with Juho Jäppinen, Hans-Peter Schütt and KSEK since 2018). She was the XXV Mänttä Art Festival curator in 2020/21.

Sympathetic resonance in music is the reactionary sonar vibration in an object caused by the vibrations of a different object: It is like the awakening of a note in something that is not actively made to sound. When I see the newest paintings by Aishe Vejdani, this is what I feel. The visual resonance sounds a similar chord in my retina, and I feel emotional waves ripple through me.

In her exhibition at Myymälä2, From Memory to Memorial (27.10. - 20.11.2022), she shows four large, dark paintings and one video piece. The paintings are skilfully painted and focus carefully on light and shadow. Figures and forms float and flow in and out of the light, which swirls like a cold fog. The emotion I feel is both light and heavy. I am intrigued by how the paintings look, both ancient and new. These works reference Aishe Vejdani’s ancestral past, including the hardship her forefathers endured, and honor these stories in the continuity of history. I have not yet seen the video piece, but these images haunt me, and for this interview, I want to look at these pieces in the context of her larger body of work and their process of creation.

When we started working on this interview, the current violence in Iran had yet to begin, and our focus was further away from the past. However, the protests and resulting state brutality have disturbed this focus, and I want to check in and make sure she can still go ahead as planned.

Untitled, 2018, oil on canvas, 110 x 100 cm. This painting was the starting point of Vejdani’s practice of her familial history. Photo: Aishe Vejdani

AISHE: Key historical events are taking place in Iran, where I come from. People, especially young women, together with young men, are risking their lives to fight for their human rights. Their bravery is inspiring the world, and the price they pay shall not be in vain. It puts things into perspective, and doing anything else that does not directly contribute to Iran’s current events feels futile. However, I have a responsibility to the memory of my ancestors through this project, to remember them with dignity and beyond what they lost or suffered in relation to political and historical events. And therefore, we can go ahead with this interview, though with a heavy yet hopeful heart.

ANNA: The history of your ancestry comes up in your work, but this does not look like a personal revelation or therapeutic catharsis for the viewer. Your images allude to a universal yet intimate past, as they remain connected to the more significant human experience within specific historical events. Previous paintings reference different forms of literature as the base of their stories, but more recently, you have focused on historical events. What inspired you to shift toward a more fact-based reference in constructing your narrative?

Thinking about referencing historical events in my practice started in 2017 when we lived in a small town in Austria bordering Slovenia. I noticed that with people we met, our conversation would naturally flow around their memories of some historical events or re-telling their parents’ memories of those events, such as independence in Slovenia or events around former Yugoslavia. Within these conversations, I became aware of how much I didn’t know about my familial history concerning specific historical events, and I got curious about why that is. I am the second generation born in Iran, and while growing up, there wasn’t much talk about our ancestors. All I knew was that they were from Turkmenistan and were land owners, which was a problem for the government of their time; some family members were shot. I had no idea within what political or historical context these events took place. I came to a point where this ‘not knowing’ was blocking my thinking. Therefore I needed to know and own our familial history concerning events that have radically changed how our lives moved forward.

I later understood that the abovementioned events took place in 1920-1930 Turkmenistan. This decade was crucial for Turkmenistan to acquire a clearly defined territory under Soviet rule. Yet, as it was happening with a mad rush, it came at a huge cost to my ancestors: execution, confiscation of property, and displacement to Iran.

From 2017-2019 I engaged my practice with my familial history from the decade mentioned above and exhibited the final work in the exhibition Laughter to Cry (2019) at B-galleria Turku. The Turku show focused on studying the transmission of our familial history of that time through memory. The exhibition at Myymälä2 is the continuation of that show from a different angle. This time, my focus has been on building a connection between the many layers of history passed through memory, such as facts around that specific timeline, my familial memory, Turkmen rituals, imagination, and projection.

When I place myself in front of the canvas, I don’t allow imaginary critics, admirers, self-criticality, or self-flattery to be in the room. I think of them as internalised characters/characteristics in relation to the mainstream. I have noticed that when my actions are self-affirmative, my ego is not blocking my practice.

Untitled, 2019, oil on canvas with a video projection, 415 x 150 cm. Installation view from the exhibition Laughter to Cry at B-galleria, Turku. Photo: Veera Ahlholm

When we are raised in a family culture that differs from the primary culture we live in, many aspects of life set us apart from the mainstream. It can be easy to return to that familiar form of social dissonance as the default perspective whenever we find ourselves in new or unfamiliar settings (taking on the role of the “outcast”). Over the years, you have consciously worked to step out of this pattern. What were some of the instances that made you more aware of your negative self-talk, and how has this change in perspective affected your artistic practice?

Becoming an outcast can very well happen within smaller units such as family settings and ethnicity in relation to different tribes, and it continues to the ones on a bigger scale. What I have noticed is that inner talk can go either toward a desire to fit into the so-called mainstream or the desire to rebel against it. In both, there is little room for the self. I’m not generally opposed to using the “mainstream” or “norm” to self-differentiate. The problem becomes when the mainstream becomes the ultimate guide in what we desire or even rebel against.

I think certain things happened during lockdowns. I found solitude during this time, and it has helped me observe my behaviour or decisions, whether they are self-affirmative or if the motives come from somewhere else. This awareness has helped me in my art practice. For example, when I place myself in front of the canvas, I don’t allow imaginary critics, admirers, self-criticality, or self-flattery to be in the room. I think of them as internalised characters/characteristics in relation to the mainstream. I have noticed that when my actions are self-affirmative, my ego is not blocking my practice.

You have packed up and moved to several countries worldwide, only staying for a couple of seasons in each place. In contrast, although your work is intensely focused, it exudes a calm aura. The unsettled, turbulent energy I associate with constant re-homing is not apparent in your work. How do you reach the eye of the storm? Or how do you establish the focus necessary to paint within the chaos of continually relocating?

It’s kind of ironic that I’m a person who needs change but doesn’t like change. Any change, whether relocating, re-homing, or a simple transition from painting to writing an application, unsettles me and requires preparation. This year, one considerable learning for me was that my tolerance for uncomfortable emotions was low and that I needed to grow more space for them. Before, I would do anything to distract myself from anxiety, stress, fear, and anger so that I won’t feel them. Well, anyone in their right mind knows that if you avoid these emotions, they come back more strongly. And yes, they returned stronger, and I would get physical ailments.

Now I meditate, sit with them, and understand what each emotion is trying to communicate, like anger shows that something needs to change. Or if I am sad, that tells me I have to let go of something. Having a constant inner dialogue to check in is a must these days for me to maintain a certain focus and calm. Yet, of course, there are good and bad days, and some days are way too long.

Also, as I was painting the memory of four of my ancestors, it was essential to maintain a certain calm so I was out of the way as much as possible. I would pray before starting each painting day, saying: God, please help me paint what want to be painted. It was my way of staying as grounded as possible and respecting my subjects.

Although many physical aspects of your work remain consistent, the subjects of your work seem to shift intentionally with each international move. Can you talk about the influence or relationship you form between the place you physically live in and the subjects you choose to paint?

For almost all of my painting series, I have used myself as a reference to paint from. The theme or the overall subject matter doesn’t change with each move. For example, this series is a continuation of my works in the Turku exhibition in 2019. In this project, subjects changed, and for the first time, I painted male figures as three of my ancestors I wanted to paint were men. If it appears that I change my subjects with each international move, it might be more due to the change in painting style or the evolution of my approach to a theme.

When I was doing my bachelor’s studies in English literature, we read about James Joyce’s novel Ulysses. I got fascinated by his writing choices as he radically shifted his narrative style with each new episode of the novel. Consciously or unconsciously, I’m hoping for similar experimentation with different styles in painting. So the desire for experimentation with different styles has always been there. It just gets unlocked by each move, I think. For the painting style of this project, I take my reference from baroque painting’s specific characteristics such as sensuous richness, drama, dynamism, and movement. As I knew I would apply concurrence of different elements in my paintings, I felt this style would allow such a thing. A so-called “signature style” would be very dull. But, of course, never say never.

And for the video work, I also see it as a different kind of painting. It’s not yet ready, so I haven’t shown it to you. For its formal decisions, I have taken inspiration loosely from the Turkmen carpet’s geometric patterns and the abstract paintings of the art movement de Stijl.

Gardener Called Gardener, from the triptych ‘Garden’, 2021, oil on canvas, 135 x 90 cm, Oil on Canvas, 2021. The triptych was exhibited at Mänttä Art Festival 2021 To Err Is Human curated by Anna Ruth. Photo: Aman Askarizad

It Is Calling, 2021, from the triptych ‘Garden’, 2021, oil on canvas, 135 x 90 cm, Oil on Canvas, 2021. The triptych was exhibited at Mänttä Art Festival 2021 To Err Is Human curated by Anna Ruth. Photo: Aman Askarizad

Your process seamlessly intertwines different disciplines, making them an essential and inseparable part of the result. I am alluding to your use of literature, history, and music in creating your paintings. For example, while you made the triptych Garden (2021), you listened to and sang a particular folk song as part of the creation process.

In your new series, the presence of music is also apparent in the rhythms and fluidity of brush strokes. I can almost hear the painting as much as I see it. What does music mean to you? And how do you continue to weave music into your painting practice?

I rarely listen to music; when I do, it’s primarily Turkmen folk songs or chants sung by women through generations. I listen to them to learn to sing or hum. Music among Turkmen has been preserved orally, generation after generation. Even to this day, there aren’t many written notes of folk music. This layer of time and how people of each generation have added their creativity based on the characteristics of their own time is very intriguing to me. It connects me to my ancestors.

I sing or hum the most while I am developing an idea. It helps me establish a mood or atmosphere. I don’t think of this atmosphere visually, but it’s more like a companion. I do apply visual rhythm to my paintings. When I do, I think of it mainly within visual parameters by repeating certain lines, shapes, and values to reach a certain visual harmony.

Of course, you can only hope that the project gets funded, but after I have sent the application, I don’t wait for their answer to start. I already start with self-assessment. I plan accordingly based on what I want to do and what skills I should develop. And I set a daily routine that is personal and sustainable to work, where I show up to work and don’t wait for inspiration.

Your paintings demonstrate extreme control. This is apparent through meticulous brushwork, color choices, and careful thought, including visual allusions to contemporary and historical references. Yet there is a hauntingly whimsical breath, figures, and forms that fade into obscurity. So that although the composition is precise and controlled in its intensity, there is still room for the viewer to insert their own experience and imagination. What framework and structures do you construct around your working process?

Before, I relied heavily on my intuition. More like, let’s just paint. Now, I try to incorporate thought processes into my intuition. These days it starts with a thought process while writing an application to funding platforms. All of these ‘Why do I want to do this?’, ‘How will I do this?’. Of course, you can only hope that the project gets funded, but after I have sent the application, I don’t wait for their answer to start. I already start with self-assessment. I plan accordingly based on what I want to do and what skills I should develop. And I set a daily routine that is personal and sustainable to work, where I show up to work and don’t wait for inspiration.

You have talked intermittently about looking for the easy way out, but your creation process looks the task straight in the eyes and dutifully ploughs towards a final goal. Recently you also spent a lot of time re-learning some basics of shape perspective and lighting. What aspects of creation do you enjoy the most - what parts do you look forward to? And finally, what makes a painting complete?

I’m not sure if I can single out some aspects. What comes to mind now about what I enjoy the most is when I put on my apron to start work and when I’m washing my brushes after the work is done. It’s like an everyday victory for me, as I never find myself wanting to work. So every day, I have to prepare myself to work. It’s like being the parent of a child who never wants to go to school.

A lot goes into defining the structure of a project, planning, and making some drafts. And I look forward to working on the final work, although simultaneously, that equally scares me.

There are many factors to help decide when a painting is complete. It is a combination of my gut feeling and how the painting has turned out in relation to my initial plans. Also, I don’t work on one painting from start to finish and then move to the next. I paint one layer of one painting, then move to the next, and later return to the first painting. I have at least four to five layers on each painting. This work routine allows time and distance to understand better when to call a painting complete.