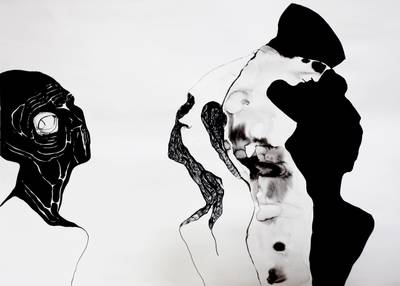

Golrokh Nafisi,خوف و رجاء (Fear and Hope), from the project Continuous Cities

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

A Busy Revolution or a Real One

Elham Rahmati

On September 16, Zhina Amini, a 22-year-old woman, was killed by the morality police in Tehran. Her death sparked nationwide protests that haven’t stopped since then. To speculate when and how this simmering discontent might lead to actual political change, many have attempted to define the scope of protests, to figure out what we are dealing with here: an uprising, a movement, or a revolution. In hyperemotional times like this, gathering one’s thoughts to come to a critical analysis isn’t exactly an easy task, especially if you’re not physically there in the protests and have to rely on social media to follow what is happening. There, I find myself constantly oscillating between the euphoria of high hope and the dread of hopelessness.

In ‘Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire’ the Champions each retrieved a golden egg from the dragons in the first task. When opened, Harry’s egg emits an unbearable screeching sound with an incomprehensible message. Harry must decipher the sound’s meaning and, through that, find a way to complete the second task. The correct way to decipher the egg is to open it and listen to it underwater. Social media reminds me of that golden egg these days (wish I had a smarter analogy). In the absence of streets where our voices can come together, many of us have bundled there, where despite the promise, few people are coming together, and many are falling apart. There are accusations, guilt, shame, anger, disinformation, bullying, labeling, and all sorts of power play, muting the formation of conversations around our thoughts and ideas for the future and our values and principles for change. How can we use our tools differently? How do we find different ways to listen? The golden egg may give us a clue here and there, but the real work is done elsewhere.

A couple of years ago, a friend with a brilliant talent for community building added me to a WhatsApp group. There were a few other women artists I either didn’t know or had only heard their names. We were put together to discuss a particular issue that was bothering us all at the same time. One of the group members suggested that we perhaps introduce ourselves to get a better grasp of who we are talking to, not by copy-pasting our artist statements or education credentials, but by making what she called ‘podcasts’ where we would tell our life stories, answering the question of what has shaped us into who we are and brought us to where we are. While listening to these ‘podcasts’, we realized how much we have in common, despite our different geographies, backgrounds, and practices. That particular issue we had gathered around was nothing but a symptom of patriarchy. That symptom went away, but, of course, not the patriarchy, so the group remained with occasional pauses in activity. With the protests starting, we came back together, all frightened and anxious to figure out what was happening and how we could contribute. We shared our fears and frustrations, as well as what brought us joy: the numerous expressions of solidarity our feminist movement of ‘Woman, life, freedom’ was receiving from women and queer voices in Afghanistan, Armenia, Rojava, Iraq, Chile, Palestine, Sudan, Egypt, Turkey, Pakistan, India, Ecuador, Lebanon, indigenous peoples in Canada, African-Americans, and others. I’ve been left speechless at the power that lies in these messages, in this coming together, this moment of realization that none of us can be free if one of us is oppressed, an understanding that is at the core of the manifesto of ‘Woman, life, freedom’.

Jin Jiyan Azadi (Woman, Life, Freedom) is a Kurdish phrase. It is rooted in the Kurdish Feminist Movement and is anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal, anti-colonial, and anti-nationalist. It is as inclusive and pluralistic a manifesto as there can be. And that makes it terrifying and confusing for some. One of the worst betrayals of oppressive systems is destroying our sense of imagination and confining it to their limited worldview, where the word ‘woman’ is only synonymous with motherhood and with bodies that need to be controlled; where Jin Jiyan Azadi isn’t a valid manifesto because it sounds too romantic for the very patriarchal minds it wishes to change; where your idea of equality means that there should be the word ‘man’ next to ‘woman’; or it may seem the revolution is excluding men. So yes, we have the most progressive manifesto, but how to live up to it?

I want us to be able to talk to each other. To find spaces on the fringes of the demonstrations for coming together beyond social media, where it is actually possible to share and discuss ideas rather than bully, dictate, scold, and reprimand. To feel free to ask questions and be critical without being put on trial for treason in the ruthless courts of social media. To not enclose our agency only to pass around prescriptions others have written for us. I want us to free our imagination from seeking solidarity and action from those who have nothing to offer us but war and sanctions. I want us to reflect on our positions as people, especially if that is a position of the majority, one that has historically oppressed minorities on the grounds of their ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and class. If you ask Kurds not to speak their language at the protest in the name of ‘unity’, you are part of the problem. If you ask a queer person not to bring their flag to the protest in the name of ‘unity’, then you are part of the problem. I could go on, but I think you understand what I’m getting at. Solidarities and connections can’t emerge between various migrant, diasporic, and transnational communities without acknowledging the exerted powers on our behalf.

I want us to grow and to give room to others so we can grow together until we are all tall enough to see the promising horizon that is Jin Jiyan Azadi.

Where there is trouble, there is also agency. Why forget that?

Vidha Saumya

We live in a world where multiple other worlds are trying to break in. Myriad issues are reaching critical mass, spilling all over us, and need urgent mopping (or immersion). It is here that key moments of learning, unlearning, and re-learning can happen. Oscillating between cautious virtue signalling and jumping on solidarity bandwagon, often we end up diluting the meaning of movements and the messages they send. But how can we stay fixed on the fundamentals of hope and knowledge and yet respond to the urgency and immediacy? Today, one such field of choice presents itself at the protests of Iranian women. They are fighting for self-determination and the right to exercise their own will.

When I look around, several ways I have learned to acquire knowledge from institutions and individuals severely clash with the knowledge I receive from these protests. Ironic and skeptic about both our own and others’ knowledges, we take nothing for granted. The rational skepticism we have been trained in has ripened into overinformed paranoia and neoliberal faithlessness. Yet knowledge is not abstract, especially in the case of these protests. It involves lives that have a deeper relationship with labour that redefines agency and braving dispensability.

Art, or the art world, which is integral to my knowledge system and livelihood, has a particularly complex stand in these regards. The awareness that contemporary art and the art world keep a hands-off approach to deeper discussions with the politics of the world, let alone admitting its own inseparable (profitable) relationship, makes me frustrated. The tendency of those involved in the arts or who consider themselves artists draw neat borders around art and politics as two immiscible territories while, at the same time, cherrypick ‘political topics’ in their most diluted forms and think that they can pass them off as legitimate knowledge, is infuriating. Symbolic re-presentation is not real representation.

In the past fifteen years of working at making art or being employed in the art world, I have observed large sections of the art world harp on the ‘cosmopolitanism of the global traveller’, who, under the pretext of ‘situated experience’, use catch-phrases of ‘home’, ‘exile’ and ‘diaspora’ to exoticise nostalgia, while remaining complicit and even benefitting from the hegemonic nation-state bureaucracies. As artists and artworkers who claim ‘borderlessness’ and universality, how come we so easily accessorise our practices with the fuzzy embrace of the most dominant signs of state powers of our choice? Despite a certain awareness, we aspire to and carry out actions in laser-cut definitions of art at times, even at the cost of movements, histories and languages that have shaped us and provided us with subliminal idioms and metaphors. Is it so difficult to grasp that subjectivity, experience, and knowledge are inherently connected and not convenient multiple choice questions? And this fundamental and constitutional connection is pivotal to conditions that frame how we think and act in the world.

An artist’s task is to make continuous efforts to break down stereotypes and reductive categories. For any artist, the ongoing protests in Iran is a site that opens up the possibility to free human thought, creating multilingual feminist communication and art. Whether it is the strong visual symbols of protest, such as the removing and burning the hijab in public spaces or the fundamental outcry of “woman, life, freedom”, this protest is visible through its many compositions.

We see the women, young adults and school-going children challenging the conditions of agency, long relegated to the easy acceptance of “but that’s how things are”. We are witnessing a loud and clear retort, but this is not how it should be. This is not how it will be. Scores of published videos, poetry, art, opinions, and news coming from the streets of Iran are indelicate, unscheduled and in permanent opposition to the status quo. They are challenging the-way-things-are with songs, posters, artworks, poems, and articles, amongst other forms of public resistance.

What can artists learn from this protest? Art world systems are often a maze of crossroads. Every decision leads to another choice, but the directions, by definition of artistic pursuits embedding decolonial and anti-neoliberal tendencies, are never clear. Making these decisions becomes easier when thought through the desire to unlearn, to begin again. In unlearning ‘ways of the art world’ (never too late), we are often at a stalemate. Sometimes there is the luxury of time and resources, and sometimes the momentum and limited tools that catapult us into choices. And the easy way out is to fall back on the dominant neoliberal idea of agency, which is an untroubled, overconfident, resolved notion of agency. It is the kind of agency that takes decision-making power from those working at the grassroots and hands it over to those who benefit from this social system. In such a situation, it is even more necessary to repeat and normalize the idea of a fractured, real, conditional, dispensable agency. It necessitates a dramatic and insurgent sense of making the most of one’s rare opportunity to speak, capturing the audience’s attention, and outwitting the opponent with wit, humour, and debate.

Recently, I was listening to an archival recording of an interview of Urdu novelist Ismat Chughtai (1915-1991). She recalls being disgusted by stories and positions of writing that constantly portrayed women being miserable and stifled – as if they had no capacity to rebel. Her heroines, on the other hand, broke away from those shackles. The agency of rebellion was important to Chughtai because their oppression in its myriad forms was always at the center of her gaze. Where there is trouble, there is also agency. Why forget that?

Protests are self-sustaining spontaneous fires. They are so because the sparks of fundamental demands are thrown over a social terrain that is not only diverse but very difficult to negotiate – for its plurality and inflexibility of rigour. It does not take long before the fire is visible, as has been evident in more than a month-long series of protests in Iran and across many other countries and groups in solidarity. Various public and private systems, such as government authorities and troll bots, try to douse this fire. Yet these fires are multiplying. So, what is making other public join to keep these fires burning? It could be the gregarious intolerance towards how-things-are to be replaced by an unquenchable interest in the larger picture, in the fundamental demands, in making connections across lines and barriers, refusing to be tied to a speciality, and caring for ideas and values despite restrictions.

Rather than waiting for the fire to go out, for the ashes and dust to settle, and for definitive scholarly summaries of it to be published, why don’t we look through the fire and smoke right now and start learning imperfectly?

Because this is how we have been taught proper knowledge doesn’t come from.