Installation view, Unity, SIC Space | Photo: SIC, 2022

Najia Fatima is an interdisciplinary artist and a writer. She graduated with a Masters in Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and earned her B.A. in Architecture and Visual Studies from the University of Toronto. Fatima’s independent art practice engages with themes of occupation, displacement, and geopolitical tensions. She has produced a collection of visual, performance, installation and photography projects; her writing, considering how the built environment manifests structural inequality, has been published in various magazines.

SIC gallery’s exhibition titled Unity began on October 7, 2022, after a lull in its programming due to a relocation to the historic Malmi station. It remained open to the public until November 13 and consisted of the works of five European artists. Curated by Ilari Laamanen, the exhibition dealt with life at various stages in relation to the larger, seemingly ineffable character of the world. The curatorial statement begins by questioning our tight adherence to an unloving system. It states:

‘Why do we cling to systems when the basic character of the world is ineffable? We get stuck in ways that don’t foster understanding and compassion. At the same time, we feel how these structures, under the pressure of which we live, sway and crumble. Thus, love.’1

The overarching subject matter remained life’s interconnected nature and the intricacies of human relations leading up to death. It included the works of Nadine Byrne, BLESS, Elina Vainio, Krysztof Jung, Alexa Karolinski and Ingo Nierman. The show highlighted a diversity of mediums; from sculptures by Vainio and Byrne to photography by Jung and film by Karolinski and Niermann. Each artist delves into the subject with a distinct approach towards issues of love, thus offering their own unique perspective on love in relation to society.

The works, in relation to each other, successfully embody the curatorial statement, ‘we are an inseparable part of nature and therefore always connected to each other.’ They weave together the concepts of life, love and death, therefore, establishing a coherent larger framework of the exhibition. This thematic consistency is also visible in the aesthetic production with a striking palette of cool earth tones. While the composition of the works within the confines of the gallery makes perfect sense, the overall exhibition raises more questions than it answers in regards to its larger socio-political implications. Collectively their works hardly do justice to the subject matter that they deal with.

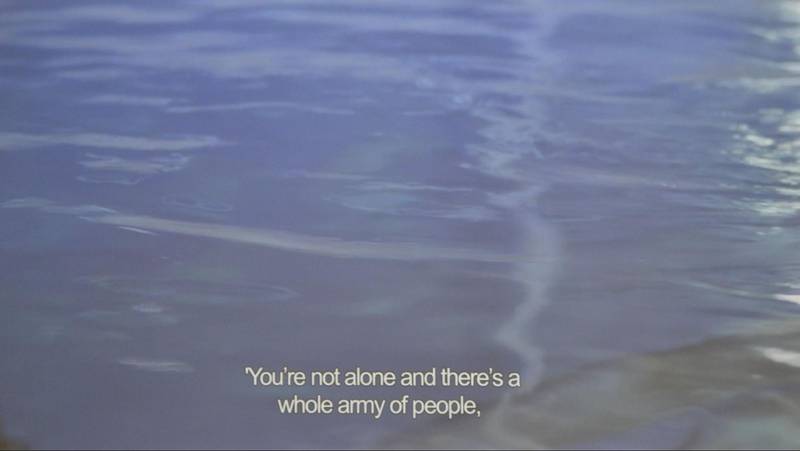

The multifaceted nature of love provides many contrasting angles that can result in an enriching conversation. This could have been especially valuable to the context of Finland with an economic recession resulting from a pandemic and an ongoing European war.2 Communities have had to reimagine how love, life and death manifest in the reality of COVID and after the recent escalation of tensions within Europe’s political climate. Some works hint towards this larger political framework, such as Karoliniski and Niermann’s 40-minute docu-fictional film Army of Love (2016). However, a project created in 2016 cannot adequately address the nuances of the European context in 2022.

The film seeks to address the diversity of love by interviewing people from various walks of life on their experiences of intimacy, loneliness, and attraction. It distinguishes between the liberalisation of love as opposed to the liberation of love, whereas the latter would result in freedom to love in an age of hookup apps.3 The film presents a utopian proposal that associates love and justice as a gesture that would break the confines of social malaise and dire loneliness.4

Alexa Karolinski and Ingo Nierman, Video stills from Army of Love, 2016, HD film, 40 min | Photo: Najia Fatima

The premise of the work provides an ideal foundation for a conversation on love with its inclusion of elder, disabled and queer folks. However, these conversations need to be supplemented with either their surrounding works or an effective curatorial intervention to relate to recent challenges. The elderly and the disabled folks in the film spoke of their vulnerabilities in finding love; one person even called it ‘wishful thinking.’5 Love already presents a challenge for disabled folks, one interviewee stated that as a disabled man, people approach him with caution due to their unwillingness to offer care.6 This hesitation in care escalated in the last few years, especially for the elderly and disabled people during the peak of the pandemic. Negligent attitudes are reflected in larger institutions such as healthcare and policy making along with its implementation by the general public. Care was denied to those who needed it most in the form of insufficient COVID protocols, thus leading to heightened social isolation and subsequent loneliness. Such a treatment upholds an unjust system resulting in an unloving social landscape.

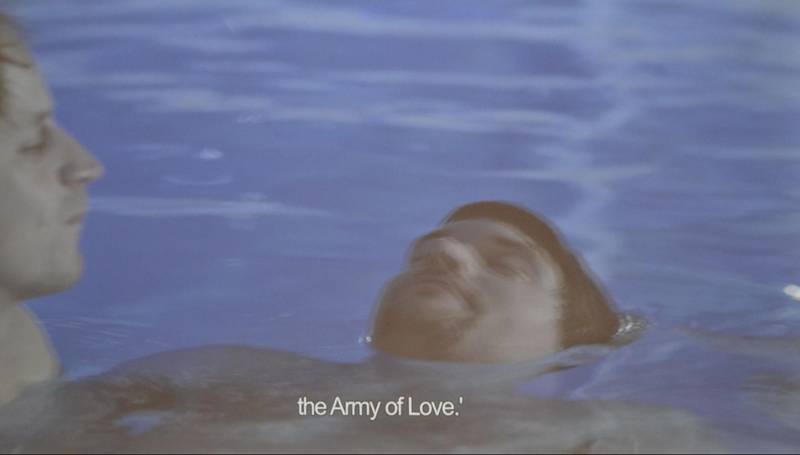

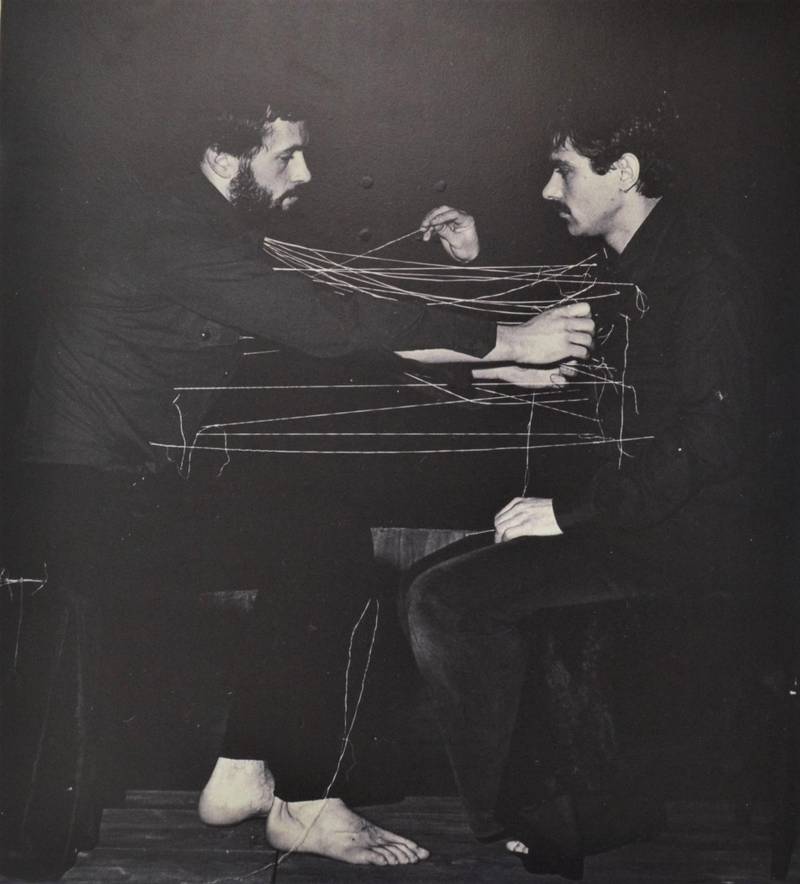

Tense social landscapes and love as a form of resistance are also addressed in Krysztof Jung’s Performans wspόlny (joint performance) 1980. The work is a documentation of photos of the performance and it is situated at the heart of the exhibition as well as in the peripheral spaces of the gallery. Krzysztof Jung (1951-1998) was a pioneer of queer art in Poland and created a majority of his work in the 1980’s.7 Through his Plastic Theatre Performances, Jung highlights the interconnectivity of emotions and intuitions in relation to intellect. He charts the physical embodiment of a sensuous experience and asks the question of gender along with it. The curatorial statement from SIC highlights a well-timed resonance of such questions in today’s context. It states ‘questions related to gender identities and corporeal knowledge are more widely addressed and appreciated (today) than during his time.’8 The statement holds truth, however, it is crucial when galleries highlight artists of the past, they also push the conversation forward. In the exhibition, Jung’s work was the only one that highlighted the question of gender in society.

Krysztof Jung, Performance Wspόlny, 1980, documentation photos of a performance, photographer: Janusz Prajs by Krysztof Jung | Photo in the exhibition: Najia Fatima

The curatorial statement from SIC highlights a well-timed resonance of such questions in today’s context. It states ‘questions related to gender identities and corporeal knowledge are more widely addressed and appreciated (today) than during his time.’ The statement holds truth, however, it is crucial when galleries highlight artists of the past, they also push the conversation forward. In the exhibition, Jung’s work was the only one that highlighted the question of gender in society.

Two of the most recent works in the show that seem to be in conversation with each other on issues of life and death are Elina Vainio’s sculpture (2022) and Nadine Byrne’s sculpture Attire for travel along the river Styx (2020). The Swedish artist Byrne’s work is a part of her ‘Work of Mourning’ and it explores the subject of grief, loss and memory. Central to Byrne’s work are objects, which, like relics of a bygone era, are filled with imprints from a life, a person or a place.9 Death impacts equally the passer as well as the ones left behind as the work highlights a funerary practice associated with the river Styx.

The river Styx was one of the five rivers of the underworld in ancient Greek mythology. It formed a boundary between the living and dead. A deceased person’s soul had to safely cross the river to become a part of the afterlife. This was a crucial journey for the spirit and its preparation took place at the funeral by the loved ones of the deceased.10 The costumes for the journey on river Styx created by Byrne, therefore, emphasise the rituals and emotions of mourning and loss.

Her work becomes a critique of how Western Society has overtime shifted from communal practices of mourning to individual grieving and collective silence. The culture has effectively erased many elements intended to communicate a state of grieving. Her costumes seek to bring back this relationship, and she creates a conversation around memory in relation to place and materiality.11 It presents a timely critique of Western Society and its anxieties related to grief. As witnessed in the events of the last few years, the crisis response to a collective traumatic experience hardly includes collective grief work.

Nadine Byrne, Attire for travel along the Styx, 2020, fabric, steel | Photo: SIC, 2022

On the opposite end of Byrne’s work is Vainio’s series of organic sculptures ( ) (2020). Vainio’s work highlights the fragility of life, a connection between humans and other life forms along with the organicism of nature.12 This is communicated through the materiality of the bone glue and iron-oxide pigment. When paired together, the two create an organic shape that evolves over time as the glue dries, thus forming a deep amber, leather-like form that resembles an empty shell. The sculpture implies the presence of an organism that outgrew and abandoned the shell that created it, therefore becoming a gesture that mimics birth.

This series departs from the conceptual elements of the works around it and focuses on the physicality of life. Without elements such as narrative or storytelling that define the surrounding works, the piece steps away from making larger social or political statements and remains honest to its own materiality. It addresses the circular nature of all things organic. Life and death are a perpetual transmutation from one form to the other, thus marking a fluid nature of growth and its embodiment in physical form.

( ) by Elina Vainio - Unity | Photo: SIC, 2022

Similar fluidity of forms is also highlighted in BLESS N°61 Swimmingtogether Bathing Blanket (2017). BLESS is a project that questions boundaries related to art and design, objecthood and usability, and private and public space.13 Swimmingtogether depicts a person enjoying an uninterrupted moment with water. The swimmer is almost completely submerged and seemingly floating with ease. The moment where the body touches the water, the feeling of melting, evaporating or dissolving becomes visible. The artist statement questions ‘What exactly are the outlines of the individual (experience)?’ This is meant to acknowledge the medium of the work as a blanket. The fabric, manufactured with interwoven threads, is an attempt to imply the larger interdependencies that inform the collective human experience. The relationship between the fabric’s interwoven construction and universal interconnection is less visible in the work unless read through the artist statement or communicated through supplementary material.

BLESS N°61 by BLESS | Photo: SIC, 2022

The show is finally accompanied with the text titled Love as Frequency written by the curator. The text begins with the curator longing for a hug, a desire that allowed him to investigate his own need for affection. He then tackles the subject through various speculations on love. It could be a passionate way of making something or the feeling of being completely comfortable in your own body. Sometimes staying silent is the ultimate form of love, and at other times it is unconditional giving. Collectively, love is about the ability to grow and transmute together; dying is also a natural part of this process. However, before all these definitions can be implemented he emphasises the need to ‘accept ourselves.’14 He finally concludes his statement in the following words:

‘In the end love is not about giving and receiving, it’s in the being. It’s not a tradeoff. Love doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with another individual, either. Love is a frequency. When being in love, it becomes clear that on a deeper level we are all interconnected. In a way, we are all one.’15

His statement swiftly moves from the collective to the individual, from life to death and from giving to withholding until finally ending with a broad statement on the oneness of the world. Such an approach towards a politically charged subject can be problematic because it comes uncomfortably close to the language of new age spiritualist movements. The discourse created by the statement revolves around concepts of the self, the moment of realisation, the internal exploration and its outward manifestation. These ideas barely embody a coherent understanding of the individual in relation to external circumstances.

It is crucial to remain critical of spaces that claim a universality without adequately centering marginalised voices. By choosing to include works that primarily centre white European voices an exclusion has already been practised. This exclusion of artists from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds along with gender identities is a part of the hegemonic systems that the exhibition is attempting to critique. Such systems form unjust structures that continue to hold power in the art world.

Furthermore, the statement clearly wrestles with the reality that love, life and death is an exhaustive subject matter and requires additional parameters to frame a cohesive conversation. This struggle is ultimately evident in the content of the exhibition as well. It’s attempting to embed itself in the current political climate however it’s at the same time equally removed from it. It is crucial to remain critical of spaces that claim a universality without adequately centering marginalised voices. By choosing to include works that primarily centre white European voices an exclusion has already been practised. This exclusion of artists from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds along with gender identities is a part of the hegemonic systems that the exhibition is attempting to critique. Such systems form unjust structures that continue to hold power in the art world.

One of the most crucial objectives of small-scale galleries, as opposed to institutionalised museum spaces, is the ability to generate a more nuanced, honest, and critical approach towards the arts. This, unfortunately, isn’t visible here due to a lack of contextual engagement in the curatorial premise. Large political issues aside, the exhibition doesn’t even engage with its immediate context in Malmi, a primarily racialized neighbourhood in the north-eastern part of Helsinki.16 Artists throughout the show, such as Byre, Jung and Karolinski and Niemann have spoken of communal practices as a form of love. An exhibition that attempts to address loving communal practices without engaging its immediate communities becomes a performance of inclusivity.

Karolinski and Niermann’s Army of Love seeks a liberation of love as a way to justice. This liberation can be understood through love with the help of the activist and feminist author bell hooks, who wrote Love as a Practice of Freedom in 1994. She states:

‘As long as we refuse to address fully the place of love in struggles for liberation we will not be able to create a culture of conversion where there is a mass turning away from an ethic of domination. Without an ethic of love shaping the direction of our political vision and our radical aspirations, we are often seduced, in one way or the other, into continued allegiance to systems of domination-imperialism, sexism, racism, classism…the moment we choose to love we begin to move against domination, against oppression. The moment we choose to love, we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others. That action is the testimony of love as the practice of freedom.’17

Conversations on love and justice without acknowledging the current power structures will ultimately lead back to the current inequitable systems. For as long as these systems remain uncontested within galleries and art spaces a conversation on love cannot claim universal interconnectedness. While love will always remain a challenging subject for artists, curators and writers alike, it would be helpful to establish a premise that guides the conversation towards an expanded social and cultural critique as opposed to a mere vacuous display of art.