WOMAN LIFE FREEDOM By Shirin Neshat, Piccadilly Circus, London, 2022

Sh S (1983, Tehran) is an art historian, researcher, and curator based in Berlin. Her work investigates the intersection of modes of knowledge production, social resistances, and the political dimension of contemporary aesthetic practices. She currently works as a cultural producer and researcher in Berlin.

A Return to Bodies

I sit in my apartment in Berlin and look at the images of protests in Iran on my phone. Hazy memories take on a new life, no longer belonging to my past. The rage, the sorrow, and the hopes are all here again. The images make me aware of the 14-year temporal gap since I left home and, at the same time, evoke vivid memories of a younger version of myself. I feel as if had never left. I see myself lucidly as a 9-year-old. I walk home from school. I wait until I am one block away from school and take off my scarf, running and singing down the street while enjoying my tiny moment of disobedience. I remember my mother coming to pick me up from school. She was stopped at the school gates. They wouldn’t let her in because of her improper hijab. I hear her shouting angrily at the school supervisor: “I will take my daughter out of this place.” But where to? I ask myself. I remember my 15-year-old self having a date in a park when suddenly a police officer arrived to arrest us. I whisper in my friend’s ear: “Run!” And we run, and we run, and we run until we are out of breath. Adrenaline runs through our bodies, and we feel warm and triumphant. We escaped; we won!

A feminist revolution is inevitably a corporeal one, and this corporeality needs to be reflected in our modes of knowledge production and representational strategies. Representations this time served not only to document and broadcast the events, but they also created a space to connect and build new networks of solidarity and care where we recognized ourselves as ‘we’.

Here, I won’t claim to be able to share the experiences of the women I am not, and I won’t give an impression of the universality of my knowledge or try to convince you that I can bring you a first-hand, easily digestible, and classifiable experience of womanhood in Iran. The only narrative I am loyal to and claim to retell is the narrative of differences and multiplicities of experiences, which aren’t easy to classify under categories such as Iranian women, “Middle-Eastern” women, or Muslim-born women.

What we experienced during the past months in Iran was a revolution of bodies, a return to the body, a reclamation and re-inhabitation of it. Those robbed of their rights over their bodies have rebelled against the oppressors. A feminist revolution is inevitably a corporeal one, and this corporeality needs to be reflected in our modes of knowledge production and representational strategies. Representations this time served not only to document and broadcast the events, but they also created a space to connect and build new networks of solidarity and care where we recognized ourselves as ‘we’. Parallel to what was happening in the streets, the mediascapes became contested spaces, bringing about not only a mere representation of the streets but also becoming increasingly important spaces of struggle. The spontaneous nature of visual communication, the transnational nature of the flow of information, and the rhizomatic, decentralized, and unofficial role of knowledge production all challenge the dominance of mainstream media and have had a clear effect on the social sphere. These mediascapes are not, however, devoid of blind spots. By pointing out these blind spots, we learn more about the many different social forces at work in the Jin Jiyan Azadi (Woman Life Freedom) movement, voices that are often ignored and left out of the mainstream media, especially in the West.

For many Iranians, this culmination of resistance and its manifestations in the streets didn’t come as a surprise since everyday resistance and fragmented revolutionary practices have been a part of our daily lives for decades. Knowing the genealogy of women’s resistance in Iran since the turn of the century helps us see recent events not as unprecedented ruptures and a sudden awakening of women in an archaic patriarchal society but as the accumulation of multiple resistances throughout our modern and contemporary history in the face of an ever-shape-shifting patriarchy.

This difference between ‘women’ as cultural and ideological composites constructed and formed subjects of their collective histories became more evident when the 1990s works of Neshat re-emerged at the entrances of galleries and art spaces in October 2022. While the images broadcast from Iran contradict such static images of the so-called “third-world Muslim woman” (in the singular), these mummified representations stubbornly occupy the public spaces of the global north’s metropoles. This gap has now become an abyss, and to understand its depth, we need to delve deeper into our historical memories and the power structures within which the mediated images are represented.

Who is this ‘Woman’?

A woman in a dress wearing thick eyeliner similar to those of Neshat’s performs a supposedly Iranian dance erotically on the left screen. A man in a police uniform on the right screen looks directly into the camera while smoking a cigarette as if he is watching us. The split suggests the simultaneity of the events but also makes the spectator aware of their position as the beholder of the gaze. The woman dances for the man as if she is dancing for us, and he is looking at her as he is looking at us, a representational strategy to invite the viewer in.

Installation view, Shirin Neshat, The Fury, Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2023 Photography by David Regen, Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery

Shirin Neshat, The Fury, 2022, Two-channel video installation, HD video monochrome, Duration: 16 minutes and 15 seconds, © Shirin Neshat, Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery

A dialectic of gaze is constructed early on. The spaces of the gazer and the performer are separated and marked. In the background, a soft female voice sings in Arabic, and the camera eventually moves to a different space. A group of men dressed in police uniforms stand in a circle and watch a spectacle in an unrecognizable dystopian place, a sort of abandoned warehouse. The same woman, stripped from her clothes this time, puts on a wig and enters the grim space of spectacle. She seductively smiles as her body turns and twists in front of the greedy eyes of men. They stand silent, almost petrified, as if they were rating her body and performance. While all the men are dressed in uniforms, a codified representation of their social authority, the woman is naked, representing defenselessness and sensuality.

The dancer approaches the man we have seen in the first shot. He blows cigarette smoke into her face—perhaps an act of refusal or symbolic violence? The seductive gaze of the woman vanishes, and her expression changes to that of disbelief and disappointment, as if she has learned something new. She stops her performance. We can see the scars and bruises on her body now as she walks back before collapsing on the floor. Still, she doesn’t give up on performing. Her seductive smile is gone. Then, without any hint, she runs out of the warehouse and into the streets of New York, where a group of young people start following her and performing a riot. Her body starts glowing, and her empty gaze gives her a messianic aura, as if she sees something beyond the diegetic space of the video that we aren’t able to see. The reason behind her sudden change of mind is unclear, and the shift between the sensual dancer in the warehouse and the silent rioter is surprising. Did she suddenly change from being an object of pleasure to a fugitive who brings riots with her to New York? Is it all that sudden? Is she all that lonely and deprived of a community that shares a history and a collective vision with her?

How do these symbolic images relate to the reality of the current struggle in Iran? What does the signifier of the female performer stand for, and in what symbolic order is the female political prisoner performing the sexualized object/woman role for her oppressive captors? Who do these images inform, and what do they communicate in the given context?

These images are from Neshat’s new video, “The Fury,” which was created in the spring of 2022 prior to the Jin Jiyan Azadi movement in Iran and was shown at the Gladstone Gallery in New York at the same time as the uprising in Iran. According to the artist, “the female protagonist in the video represents a female Iranian political prisoner who has escaped the country after incarceration and rape to live freely in the United States, but her traumas of imprisonment and the violence she has experienced keep haunting her in her new home.”

How do these symbolic images relate to the reality of the current struggle in Iran? What does the signifier of the female performer stand for, and in what symbolic order is the female political prisoner performing the sexualized object/woman role for her oppressive captors? Who do these images inform, and what do they communicate in the given context?

Neshat directs the spectator’s gaze to the center of the scene, where the vulnerable body of the woman has turned into an object of male pleasure. The spectator’s gaze and that of the male officials overlap and ultimately unify through a process of ego identification, one that Laura Mulvey calls “the construction of a combined gaze in the traditional male-dominated Western cinema.”1

In Neshat’s video, the representation of the female body operates on two registers: as a generator of erotic pleasure for the main characters and simultaneously for the extra-diegetic spectators. This voyeuristic position ties the position of the spectator to that of men in the diegetic world of the film, creating an illusion of control and possession of the woman‘s body through unifying scopophilic pleasure. The woman is reduced to an object of pleasure on display in both positions.

It is true that artistic creations construct representations, whether mimetic or symbolic, to accentuate and express the state of reality they refer to, but can the recreation of the same violence through subjecting the female body to the same trauma the work tends to criticize be read as representing the reality? And more importantly, to what degree do these symbolic representations relate to and represent reality?

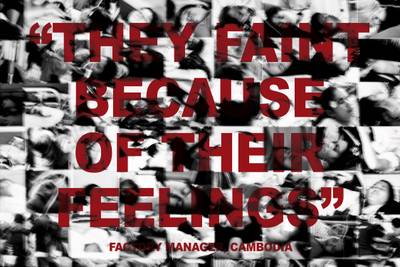

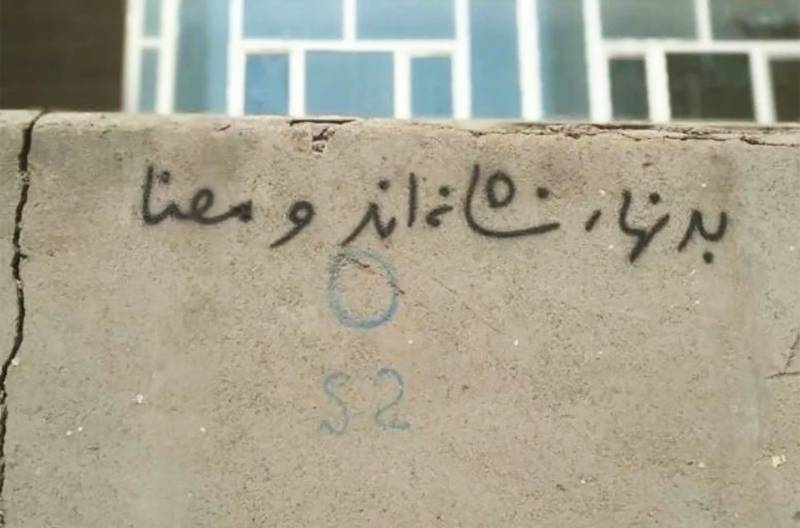

Graffiti on a wall says, ‘Bodies are signs and meanings’, Iran

Women’s protests in September 2022, Iran

Bodies as Signs & Meanings

I see a woman on my screen. Her hand swings and dances in the air while she tightly ties her hair as she prepares to fight the riot police. A woman with her hair free jumps on a dumpster bin in Tehran and starts throwing stones at armed guards. A Kurdish girl stands above masses of citizens on the top of a car, as if she is the conductor of an orchestra in a revolutionary song where each body turns into a musical note flowing from the highways in Kurdistan to the cemetery where the citizens farewell yet another young life lost. Another woman stands atop a car; she has set her headscarf (forced on her) on fire while showing with her other hand a sign of victory. A group of women dance and sing around the fire while holding hands in Bukan in a ceremony to celebrate life and collectivity. Liberated bodies come together, find each other, and share common dreams, visions, and desires. I see a Bakhtiari woman who has lost a son dancing at his funeral with other women, where the borders between pain and joy are distorted and the immense pain of loss and the joy of liberation intertwine. Schoolgirls in Sanandaj have taken off their mandatory scarves; they run through the streets, singing and chanting: Jin Jian Azadi. I see a woman standing against the water cannon truck in Tehran, having nothing but her body to bring to the front. A group of female political activists in front of the prison sing: “For dancing in the streets, for not being scared anymore, for a future when we laugh, for a simple kiss.”

People protesting in September 2022, Tehran, Iran

The main character of Neshat’s Fury, the political activist who tries to please the authorities, is nowhere to be seen here. She is the spectre of a centuries-old archetype produced and reproduced elsewhere, not here, not where these women stand. She appears and reappears unchanged from the depths of a fantasy. Who is this woman who colonizes the heterogeneities of the lives of women, composing this singularity of womanhood?

These figures of feminine resistance, of liberated bodies, of desiring subjects demanding, chanting, and dancing to the pure joy of life, mourning the loss of their children, friends, and family, and yet not giving up, stand in stark contrast to images of Neshat: the performer of pleasure rather than its owner, an object of male desire and not the desiring subject. The images of the resisting woman coming from Iran are not made to please. The dancing women, the mourning women, the women who set dumpsters on fire, the women who stand alone against the armed riot guards, satisfy and animate no one’s desires but themselves and those who share with them the here and now of the “event.” These images are only the surplus of the moment, exceeding it and leaking onto an observer‘s screen. They are not bodies in need of catering to the desires of gallerygoers ‘elsewhere.’

Neshat’s representations of womanhood are constructed in this ‘elsewhere.’ They operate on a unifying and flattening register, oblivious to the multiplicity of the inhabited experiences of womanhood within their histories. The ahistorical and static notion of womanhood based on merely sexual differences creates what Chandra Mohanty calls the "Third World Difference."2 This approach not only shapes a monolithic archetype of oppressed third-world women but also constructs a homogenous notion of patriarchy, which colonizes and dominates the complexities and diversities of womanhood across registers of class, culture, ethnicity, religion, and linguistic differences. This process does not come without political implications. Rather than shedding light on heterogeneous sources of power and oppression, it assumes an unchanging and ahistorical male dominance and patriarchy, and therefore it prevents the emergence of real strategies of resistance against them. By deleting any historical and contextual hints, not only is agency taken away from women but also these complex structures remain invisible.

These figures of feminine resistance, of liberated bodies, of desiring subjects demanding, chanting, and dancing to the pure joy of life, mourning the loss of their children, friends, and family, and yet not giving up, stand in stark contrast to images of Neshat: the performer of pleasure rather than its owner, an object of male desire and not the desiring subject.

Shirin Neshat’s work ‘Unveiling’ hung by Neue Nationalgalerie in solidarity with the 2022 protests in Iran, Berlin 2022

In October 2022, the photographs from the series Women of Allah (1993–1997) were shown again in London at Piccadilly Circus and in Berlin in front of the Neue Nationalgalerie. The subject of the 90s series of photographs is often a veiled Neshat, sometimes faceless and completely covered, who is either praying or pointing her gun to the camera, and is a reminiscence of certain images from the late 70s and early 80s broadcast from Iran by the western media. The use of self-portraits for the depiction of an experience Neshat has never lived, leaves many questions unanswered. It is unclear if her ‘Women of Allah’ are content with their situation or not, and who they really are. While in post revolutionary Iran, for many women, veiling has been and is a personal choice and not a symbol of inferiority or a lack of agency, many women were forced to wear the new Islamic dress code against their will. Can a woman who has lived through such a force afford to be so enigmatic about her experience? The reappearance of such portraits stirred critical reactions among Iranian artists. Specifically, those in the diaspora who have suffered from the stereotypical and humiliating archetype of oriental oppressed women have been debating the effect of such representations in the aftermath of September 2022 events in Iran.

Shirin Neshat, Untitled (from Women of Allah Series), 1994/2015, Silver gelatin print and ink, 60 x 42 1/4 inches (152.4 x 107.3 cm), © Shirin Neshat, Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery

The persistence in choosing to exhibit these images is an escapist strategy of hiding in a safe and known fantasy rather than looking at reality. The role of colonial and orientalist discourses in image-making and their mutual relationship with the politics of dominance imposed on different geographies of the global south have been studied in depth by many scholars in the past. In postcolonial criticism of the representational politics of Western art and literature, it is well observed that the arts and literature do not operate merely on a mimetic premise but fulfill a generative purpose in constructing a hegemonic view.

Linda Nochlin, the feminist art historian, points out two characteristics of Orientalist representational regimes: the “reality effect” and "the strict avoidance of any hint of conceptual identification or shared viewpoint with their subjects."3 The aestheticized images of the series from the end of the 1990s, “Rupture,” depicting Iranian citizens in an atemporal and ahistorical setting while doing obscure rituals, frozen in time, are an example of such a reality effect. While the photographic apparatus creates an illusion of the realness of the depicted scenes, the temporality and historicity that are vital for understanding a situation are absent in these images. The genealogy of feminist resistance in Iran is rendered invisible in favor of the eternal and mystified Orient, which at times, through black-and-white photography and deserted landscapes, becomes sinister and deeply “othered” and alienating for many Iranians. The depicted Orient is sensual but dangerous, mysterious but baleful. This amalgamation and juxtaposition of certain meanings and their attribution to the Orient is what Linda Nochlin calls “the standard Topos of Orientalist ideology.” The images that oscillate between phantasy and reality—images of harams and bazaars and public baths with female nudes, passive and sexually available, and turbaned and sworded men in the 19th century and at the height of European colonization of the East—have accompanied the fantasies of dominance over the bodies of the east encoded through the image of the female body, the object of desire.

This deeply embedded image of the East in the historical memory of the West has undergone many changes in the past decades. In the case of Iran, the televised events of the occupation of the American embassy in Tehran and the hostage crisis are the starting point of a historical shift in such representational strategies. According to Monica L. Coscia4, the void of almost no news and images from Iran had been suddenly filled with the hostage crisis, which on Nightline was presented as “taking hostage a nation.” At this historical turn, the image of Iran becomes that of the armed fundamentalist men and their female counterparts, ready for jihad against the West, and any other image or voice has been rendered inaudible or invisible for years.

This decontextualized female body, indifferent to the complex matrix of power that constructs the signifier of womanhood, rather stems from the artist‘s imagination and choices and barely reflects the reality of womanhood in post-revolutionary Iran, which she claims to depict.

The meaning of Neshat’s work and her representational choices are exactly to be found in this spacious-temporal complex of history and power relationships between the West and the East. Neshat, who left Iran in 1975 and entered the University of California to study art, has not lived in post-revolutionary Iran, and the source of inspiration for her works in the 1990s series “Women of Allah” and “Rupture” is her 1990 short trip to Iran. The circulation and visibility of these particular images have come at the expense of the invisibility of all the other possible images of women’s resistances throughout the years. This decontextualized female body, indifferent to the complex matrix of power that constructs the signifier of womanhood, rather stems from the artist‘s imagination and choices and barely reflects the reality of womanhood in post-revolutionary Iran, which she claims to depict. What forms of feminist resistance we have fostered in our daily lives and how undeniably multiple and diverse the category of ‘female’ and ‘femininity’ is in relation to ethnicity, religion, and class don’t seem to matter for the image maker. The veiled and armed women of Neshat took over the streets and screens and spoke instead of us. We, who have been rendered silent on both representational fronts.

But change is inevitable. The women silenced for too long grow louder and fiercer, as do their images. The body that fights for her liberation in the streets takes over the screens. Her gestures, charged with her memories of a thousand refusals gathered and condensed for this moment of manifestation, flow onto the screens. Her hands are wide open, embracing a new world in the making. Instead of a gun, her hands reach out to hold the hand of the next woman, building a circle of power and joy. The disobedient body, the rebellious body, the body that dances in front of the water cannon, the body that falls and stands up again and again, draws in front of us a new site of imagination and resistance.

Women’s protests in September 2022, Iran.

Protesters against the veil, protected by young men, march in central Tehran on March 10th, the third day of demonstrations for women’s rights in the Islamic Republic of Ayatollah Khomeini. Getty Images

Transgenerational Memories of Resistance

Knowledge always extends through time; it possesses a past and faces a future. In addition to our own inhabited knowledge of our daily resistances, many of us carry within the transgenerational memory of our mothers’ and grandmothers’ struggles. Modern feminist struggles in Iran began in the late 1800s, during the “Mashrooteh” constitutional revolution, which gave Iran a parliamentary government and limited the power of the king. At the beginning of the century, as Iranians questioned the omnipotence of the king and the royal family, the first feminist movements sprouted in Iran. Iranian female writers and publishers released the first issue of women’s periodicals, and many women actively pursued programs for women and girls, their education, their rights of custody and divorce, and their right to equal participation in society.5 In the aftermath of the century, many feminist organizations formed, and many women were fighting spontaneously on the two fronts of feminism and anti-imperialism. The complex relationship between the state-building power of the Pahlavis in the wake of modernization in Iran and the frictions between Reza Shah, the clergy, and the feminist movements and resistances is a topic that merits its own essay6, but what is evident is that during the Pahlavi time as well as the post-1979 Revolution, women have been tireless subjects and agents of historical change who continuously resisted multiple forms of religious, class, ethnic, and gender oppression.

A familiar scene embedded in the memory of many of us comes perhaps from the images of the Women‘s March on the 8th of March, shortly after the introduction of the Islamic dress code for women, when tens of thousands of women took to the streets against the compulsory hijab law and new restrictions against women in the country. The images of protests, where veiled and unveiled women joined forces to fight for their rights over their bodies, didn’t gain much circulation and mostly remained unnoticed in favor of the sinister image of the mysterious fundamentalist woman, sometimes faceless, sometimes with a gun in hand. Like many other images from Iran in 2022, this image crystallizes the faces of thousands of women as active subjects of their collective histories: distressed, angry, yet hopeful. Invisible to the camera’s lens, there is a vision of a future free of oppression, uniting them in this moment and in many other moments.

Iranian women protesting against the Hijab law in Tehran in 1979. Photograph: Hengameh Golestan