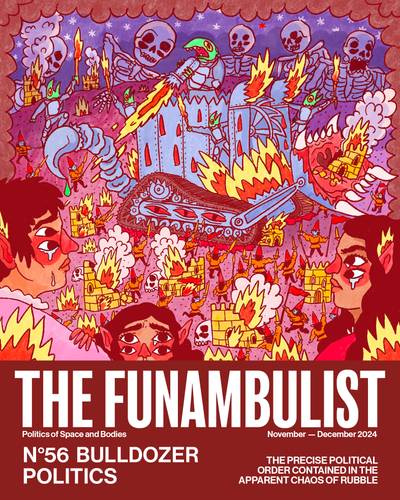

Illustration: Osheen Siva

Abinaya Nathan is a London-based Eelam Tamil activist and former editor of the Tamil Guardian. Through her writing, she explores how Eelam Tamils in the homeland and diaspora are portrayed in the media and academia. Abinaya currently works in climate campaigns and is undertaking a Master’s degree researching the intersections between conflict and climate activism.

Vanessa Vigneswaramoorthy is a Tamil settler writer, artist, and researcher, born and raised in what is now called the Greater Toronto Area. She has previously worked with the Tamil Archive Project, Tam Fam Lit Jam, and Heritage Toronto, and her creative work has been published in Q/A Poetry, Kiwi Collective Mag, and Living Hyphen Magazine. She is currently working on an MA in Adult Education and Community Development, looking at Tamil diasporic experience and anti-oppressive futures.

Abinaya: One thing that shocked me when I became exposed to the world of academia in my early twenties was how popular Eelam/Ilankai Tamils were as a research issue. For most of my childhood and early adulthood, I was intrigued by and grasped onto representations of any kind. Growing up in the UK, we were dwarfed by the huge North Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi populations whose representations of the subcontinent dominated the mainstream. While I do not believe in representation politics, I recount this to underscore that outside of the occasional foreign correspondent piece on the war, my own community and my homeland rarely made an appearance, at least in the culture I consumed. But academia is another world entirely.

While we both have gone into postgraduate study focusing on different aspects of our community, one of the things that has bewildered and intrigued me in equal measure is the existence of innumerable research papers, books, and articles on sometimes mundane, sometimes intimate aspects of Tamilness, produced by people outside the community. Where the author has been Eelam Tamil, beyond a nominal acknowledgement, I often feel an uncomfortable sense of the author having to shed their ‘Tamilness’ in order to meet the rigid norms of academia.

Both of our publications came into being then to challenge the absence of Tamil voices writing and talking about ourselves at times when there was plenty of studying and analysis of our communities by outsiders.

Tamil Guardian was created, alongside TamilNet, in the 1990s to challenge the way the armed conflict and Tamil liberation struggle were reported in the Western and global mainstream in English, as foreign correspondents were predominantly based in Colombo and got their information from Sri Lankan government sources. Both teams at the time had a direct line to the de-facto state of Tamil Eelam and its administration in the Vanni, as well as to civil service networks in Jaffna and the East. They played a vital role in combating Sri Lankan government propaganda, including by reporting numbers of civilian casualties that the state always underreported.

Vanessa: I kind of fell into editing Tamil Futures 2020. I joined the Tamil Archive Project (TAP) around September of 2018 with the intention of wanting to work with other Tamil folks on creative endeavors. I have a creative writing background, and I’ve published and edited for arts magazines before, but I always hesitated to join any Tamil arts groups or collectives, mostly out of a fear of not being qualified enough to talk about Tamil issues. What I liked about TAP was its focus on creative archiving and documenting histories that were not otherwise recorded. There is power in chronicling what is considered mundane as historically significant, in assigning importance to what would otherwise be erased. That’s the work I always wanted to do, regardless of what I was working on.

Shortly after I joined the collective, TAP put out a call for submissions for what would eventually become Tamil Futures, and I was happy to take on that editorial role. We ended up getting submissions from all over the world, from people with a variety of backgrounds. At the time, there were few English-language arts magazines aimed solely at the global Tamil community, so people were eager to be a part of it. Because we were a grassroots collective sourcing from a mainly Tamil audience, there was much less pressure to write something appealing to non-Tamil people. I think that played a big part in the submissions we got because the submissions we got were clearly written with other Tamil people in mind.

I feel, and maybe you can speak about this from the perspective of your work at Tamil Guardian, that there’s this pressure on English-language Tamil publications to write as if non-Tamil people are watching. When I was an undergraduate taking creative writing classes, I was always hyper-aware that I was often the only Tamil person in the room, and so I felt that I had to do this work to represent Tamilness without getting too messy—poems about appealing aspects like mangos and coconut oil and saris, or the pain of diasporic longing and intergenerational trauma—things that others can empathize with, or at the very least, pity. But when you’re sitting in a room with just other Tamils and our allies, you can get into the nitty-gritty, speak about gender and caste and sexuality, race, and faith, discuss complicated identities, and inter-community conflicts.

The connection between the homeland and the diaspora was at its most vulnerable, with the criminalisation of many diaspora advocacy organisations and activists and intense surveillance of the Tamil population at home. Tamil Guardian’s priority was again to raise the voice of the Eelam Tamil polity in the homeland, as well as provide a grounding for advocacy efforts in the diaspora.

Abinaya: For me, joining Tamil Guardian back in 2012 was a natural progression from student activism. I dipped my toes in gently at first. In fact, my first article was a film review. While I was used to protesting and organising exhibitions and cultural events, I never imagined I would eventually, and pretty quickly, be writing political analysis and engaging in advocacy efforts that would one day have a significant influence on foreign policy. It was an interesting time, and many Tamil organisations were at a crossroads. Three years after the end of the armed conflict, the Tamil struggle had fully transformed into one of advocacy and campaigning. It was the year that the UN Human Rights Council passed its first resolution calling for justice and accountability for wartime atrocities. But it was also at the height of the Rajapaksa regime’s reign of terror.

The connection between the homeland and the diaspora was at its most vulnerable, with the criminalisation of many diaspora advocacy organisations and activists and intense surveillance of the Tamil population at home. Tamil Guardian’s priority was again to raise the voice of the Eelam Tamil polity in the homeland, as well as provide a grounding for advocacy efforts in the diaspora. It was a challenging time, with little resources in London and having to keep connections with journalists on the ground covert for fear of retribution. But again, it was vital work. We still remain the only English-language platform to consistently and regularly provide reporting from the Tamil homeland.

Tamil Guardian has always reported on the diaspora in parallel with homeland news - for example, when it was a fortnightly paper in print, cultural events, community news, and even celebrity gossip filled the spaces between stories from the frontlines of the armed struggle. While we have continued those efforts, such as with a resident film reviewer and coverage of community events, there is no doubt that with the limited capacities and resources we draw upon, the portrayal of Tamilness sometimes seems homogenous, and some perspectives, especially those from the margins within our own communities, are lost.

This is where I feel Tamil Futures filled a gap by seeking out those stories. I remember reading a piece in one of the issues that really moved me. It was written by a young person whose family was directly impacted by the Tamil gang wars in London in the late 90s. This is a period of recent history that we’ve almost buried from our communal memory, especially with everything that came after the genocide. But it was a reality that many of us grew up with and lived in the shadow of. In my area, more people outside the community thought that the ‘Tamil Tigers’ were a gang and were clueless about the actual militant organisation and the liberation struggle. Tamils were criminalised on many fronts, terrorists in the homeland and violent thugs in the diaspora. Although reading that story unlocked memories of growing up amidst violence and of knowing people who had been involved, imprisoned, and even killed, I realised that, while I had been able to stow away those memories, there were Tamil people whose lives had been indelibly marked by these events, and whose stories were rarely told, even within our community.

In my own written work, I tend to write solely from the perspective of the diaspora because that is the backbone of my story: being of Ilankai Tamil descent as well as part of the diaspora, having my family displaced by war, and relearning my ancestral culture away from the land that it flourished on.

Vanessa: Through editing Tamil Futures, I was introduced to different forms of Tamilness that I wasn’t familiar with, and in some cases, wasn’t even aware of – Tamils whose families landed in other nations during the war, Tamils who entered the diaspora through indentured servitude, Tamils who lived in the same area as me but whose experiences were coloured by differences in neighbourhoods and family dynamics. I dealt with a lot of anxiety, during that time, about the editorial process because they were so personal to the contributors yet vital to this global Tamilness we were trying to define through the magazine, and I had to make sure we were keeping the spirit of the individual piece while making sure everything is readable and consistent.

When I’m doing editorial work, I feel like I have a bunch of different voices in my ear because there are the writers, the other editors, and the potential audience, and I’m trying to develop something that will impact all of them. I don’t want to potentially derail someone’s personal narrative because I think it’s a gift that they’re willing to share in the first place. There is a vulnerability in writing about yourself, especially in writing about how you may or may not be different from the reader, and I try to respect that.

In my own written work, I tend to write solely from the perspective of the diaspora because that is the backbone of my story: being of Ilankai Tamil descent as well as part of the diaspora, having my family displaced by war, and relearning my ancestral culture away from the land that it flourished on. Beyond my experience as Tamil, I’m writing from what is known as Canada, so my writing is complicated by location too. How do you write about being displaced when you grew up on land stolen from Indigenous peoples? How do we discuss racism and xenophobia against Tamils while speaking about anti-Blackness in our community in the same breath? How do you speak about the homeland when you’re on the other side of the globe? How do you advocate for our queer and trans kin globally without imposing a Western sense of sexuality and gender on them? In editing Tamil Futures, I got a lot of insight on how to answer those questions from people both nearby and across oceans.

I’m drawn to this quote by writer and editor Kitana Ananda, that “public engagement with wartime suffering has come to define what it means to be a Tamil living outside Sri Lanka, even among those who generally stay away from the domains of ‘politics’ and the ‘political’. The war has become so integral to the diasporic experience of Tamils and to the narratives around our community organizing that it swirls around the edges of a large part of Tamil Futures. But I think the other side of that is that there’s less space for the narratives that stray from it, stories about what happens after the war, before the war, or to Tamils who never experienced the war but felt the same or similar echoes of it written into their DNA. I think we have stories as a people—colonialism, the war, the refugee systems, intergenerational trauma—and then stories as individual people—what happens to the refugee when she lands, what happened after that family was split years ago, what happens to the boy with only second-hand memories of his homeland. I think that’s what makes Tamil Futures so impactful—it told the stories in-between these overarching narratives of what it means to be Tamil in the diaspora and the homeland.

I think with Tamil Futures, we were very lucky with the contributions we got, and we were blessed with an enthusiastic reception. I served as poetry editor for Tamil Futures 2021 and then took a step back from the team, but I’m still grateful to have worked on the project.

I think we have stories as a people—colonialism, the war, the refugee systems, intergenerational trauma—and then stories as individual people—what happens to the refugee when she lands, what happened after that family was split years ago, what happens to the boy with only second-hand memories of his homeland. I think that’s what makes Tamil Futures so impactful—it told the stories in-between these overarching narratives of what it means to be Tamil in the diaspora and the homeland.

Abinaya: My personal writing has also oscillated further towards a focus on the diaspora in recent years and on my own experiences as a London Tamil. But I think for me, the homeland is always present, a non-human actor guiding every narrative I navigate. Unlike most of my generation, I was born in Jaffna, but I don’t think that explains it since I have been in London since the age of three and consider English my first language. I think instead that the UK, or maybe even the wider European Tamil diaspora, is a perfect illustration of how porous the border between homeland and diaspora is if it exists at all. While Tamil migration is often categorised into waves corresponding with stages of the armed conflict, a steady stream of new arrivals, including refugees, continue to arrive in Europe. Many Tamils, especially in the UK, are active in domestic politics and campaigning, but it is almost impossible to think of policy issues such as immigration without thinking of how they affect Tamils in a specific way. Just last week, it was revealed that Tamil asylum seekers stuck in Diego Garcia were deported to Rwanda by the UK government. Despite having participated in protests against the Rwanda policy when it came around and celebrating the halted flights from the UK, it still shocked me to see how quickly Tamils were impacted.

Even outside of activism, so much of my social and personal life has always involved what researchers might call “performing Tamilness.” This could be as literal as participating in cultural endeavours as a child and attending weekly functions at the height of the wedding season. But it also means in mundane ways, possibly due to having lived in areas with significant Tamil presence, such as speaking in Tamil to shop staff and befriending Tamil women at the gestational diabetes clinic. These different interactions demonstrate that within the diaspora, different people hold the homeland in different proximities, but there is still a critical mass who hold it close.

While Tamil Guardian was initiated to bring the Tamil perspective to the global news landscape, it also provides a platform for the Tamil diaspora to keep connected with the homeland and with each other, which contributes to keeping alive those nuanced perspectives of Tamilness, along with platforms like Tamil Futures, which emphasise that stories are told not only by us but also for us.

While I appreciate the drive to seek out stories that don’t directly connect to the war, I don’t think there is a single issue in the Eelam Tamil community that won’t lead back to it in some way. Social media has been a boon for Eelam Tamils to carve out our own spaces and tell our own stories, but one thing that concerns me is that as generations of diaspora become more distant from the liberation struggle, the genocide, and displacement, our community’s stories risk being assimilated into the wider immigrant/diaspora narrative. I’m glad Vanessa mentioned the mango and coconut oil poetry because although it’s become a bit of a meme now, it’s still quite a dominant narrative, especially on the more visual platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, where the pinnacle of diaspora resistance seems to be wearing luxury ethnic clothes and flowers in your hair (I won’t even go into gender norms here).

I always think Eelam Tamils haven’t had the luxury of writing mango poetry (which is a shame because our native breed, Karuthakolomban, is genuinely the best breed in the world). The most popular genre of ‘Eelam Tamil diaspora back home’ photography I’ve seen on Instagram is of the ruins of ancestral homes, last inhabited in the 1980s or early 1990s, often with close-ups of bullet holes in the walls. We are a refugee diaspora, yet we risk coming full circle in the representation gap by adopting certain narratives - ‘our parents came here for a better life’, as opposed to ‘our parents fled genocide’. While Tamil Guardian was initiated to bring the Tamil perspective to the global news landscape, it also provides a platform for the Tamil diaspora to keep connected with the homeland and with each other, which contributes to keeping alive those nuanced perspectives of Tamilness, along with platforms like Tamil Futures, which emphasise that stories are told not only by us but also for us.