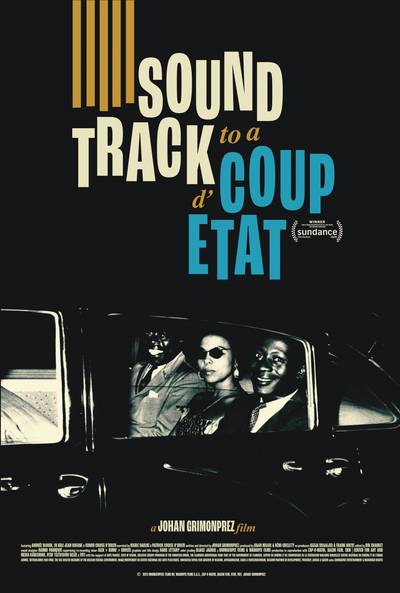

From the Untitled (Sakada) Installation, 2012/2022

Stephanie Misa (PHL/ USA) is a visual artist and researcher whose work centers around decolonizing methodologies. She consistently follows her interest in complex and diverse histories through her various multimedia installations and performances. Her artistic practice connects multicultural collaboration, curating and feminist criticism. In her doctoral research, Misa examines phenomena pertaining to the oralities and the richness of multilingualism.

Most Filipino immigrant stories refer to a movement away from the “motherland.” When you are away from your own kind, who are you in this new place? My grandmother’s is a story of assimilation and a journey that returns “home,” where “home” felt as foreign as being away. As Stuart Hall so aptly says, “If this paper seems preoccupied with the diaspora experience and its narratives of displacement, it is worth remembering that all discourse is ‘placed’, and the heart has its reasons.”1

This essay centres around a displacement and a discomfort—a translocation that spans geographies, islands, and oceans—and a dissection of a moment in time where different histories and individual stories have collapsed together under the weight of continued imperial rule. The art installation, Untitled (Sakada), weaves these stories together materially, as much as this essay offers a weaving through words.

i. micro and macro histories

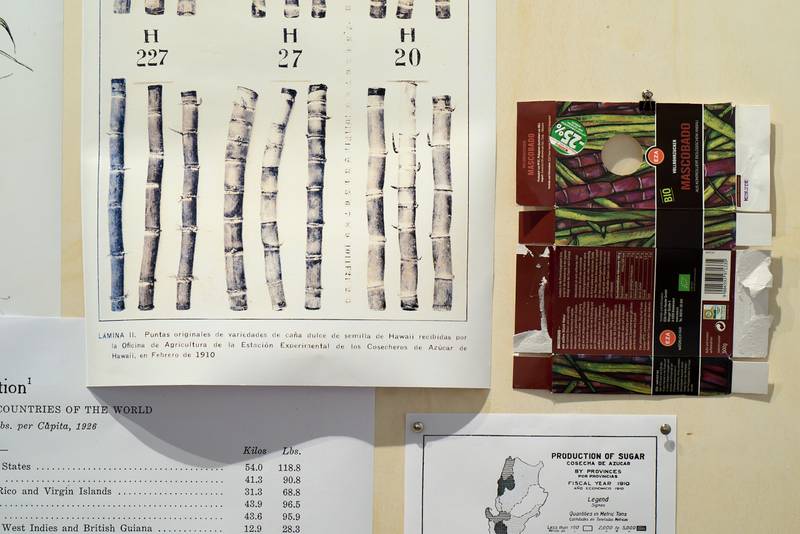

Untitled (Sakada) (2012/2022) is an installation project that deals with my grandmother’s personal photographic archives, juxtaposing these with magazine articles and writing on the US’s imperialist turn. Untitled (Sakada) examines Philippine-Hawaii relations at the turn of the nineteenth century, during which both were US territories. The project is guided by interspersed narratives and different testimonies (both archival and personal) as it uncovers the state of labor rights during a turbulent colonialist period in US history while seeking to mend the gaps in my family’s own fragmented history of diaspora and return. The work comprises a video, several sculptural interventions, lithographic prints, photos, and a vinyl record.

It is hard to trace familial histories through the interstices of larger and grander Histories—like, for example, how on December 10, 1892, Spain and the United States signed a Treaty of Peace in Paris wherein Spain ceded Puerto Rico and the island of Guam to the United States and sold the Philippine Islands for $20,000,000. Or how earlier that same year, on June 15, 1892, the U.S. Congress passed Resolution 209-91, known as the Newlands Resolution, which was signed into law by President McKinley on July 7, 1898, officially annexing the Hawaiian Islands. The Philippines, as an American colony, then became a ready source of uncapped labor for the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) as the US endeavored to cultivate the newly annexed territory of Hawaii.

Amid these vast colonial shifts and expansive redistributions of global and economic power was my grandmother’s father, Cayetano Ligot, a high school principal who just happened to know how to speak English. Growing up, the story would, of course, be narrated to me as an epic saga: how a lowly teacher became the Acting Governor of Laoag, Ilocos Norte, and then assigned as the first Resident Labor Commissioner of the Philippines to Hawaii.

This ongoing research has been with me for more than 10 years now. What started as a fascination for my grandmother’s origins has turned into a socio-economic and political unearthing of the Philippines’ relationship to its former colonial master, the United States of America. How this relationship would dictate the movement and displacement of more than 100,000 Filipino sugar cane workers and how my own family would unwittingly play a role in this diaspora became a central question to the research.

The recruitment of Filipino laborers for the Hawaiian sugar cane plantation started in 1906 and reached its height in 1923. The Ilocos Norte Province was a favorite for recruitment, as the area had previously been cultivated by the Spanish to grow sugarcane. With the agricultural know-how and expertise vestiges of Spanish colonialism, Ilocanos became the largest Philippine ethnic group in the Hawaiian plantations. Complaints had steadily been lodged about the mistreatment of Filipino contract workers on plantations. After a string of “visiting investigators” failed to represent the real working conditions of Filipino farmers (as suspicions were that their similarly worded reports were due to data mostly furnished by the HSPA themselves)2, the Philippine territory decided to install its own resident Labor Commissioner to report directly to the Governor-General of the Philippines, Leonard Wood. That man was to be my great-grandfather Cayetano, having been blessed with not only knowing English but also Ilocano. Recruitment would last for 40 years, finally ending in 1946. These laborers who left for Hawaii were called Sakadas, a term derived from the Ilocano phrase sakasakada amin, meaning “barefoot workers struggling to earn a living”.3

This ongoing research has been with me for more than 10 years now. What started as a fascination for my grandmother’s origins has turned into a socio-economic and political unearthing of the Philippines’ relationship to its former colonial master, the United States of America. How this relationship would dictate the movement and displacement of more than 100,000 Filipino sugar cane workers and how my own family would unwittingly play a role in this diaspora became a central question to the research.

The different sources for this information had me scouring the American Historical Collection Archive (AHC) at the Rizal Library of my alma mater, the Ateneo de Manila University. The AHC, established in 1950, consists of some 13,518 books, 18,674 photographs, and other materials related to the American experience in the Philippines and the relationship between the two countries, including of course visceral newspaper clippings of America’s suppression of the Philippine “rebellion” and its notable anthropological expedition of the studying of the peoples of its colonies. There were no exceptional notations on the movement of contractual laborers between the newly minted territories of the United States though. What instead was prominent in the archive was the movement of goods from the colonies into the world market, as countless lists and indexes of the Philippines’ yearly exportation of sugar, hemp, tobacco, coconut products, and other raw materials.

My family’s journey was defined by sugar.

From the Untitled (Sakada) installation, 2012/2022. Photos by Daniel Hill & Oliver Cmyral

ii. Cayetano Ligot

Ligot was fairly unpopular during his tenure as Resident Labor Commissioner of the Philippines to Hawaii, often accused of working for the interests of the HSPA rather than assisting the Sakadas in their grievances. The Hanapepe Strike of 1924 would be the height of this unrest, ensuing in a stand-off between Ligot and labor organizer and fellow Filipino, Pablo Manlapit.

Manlapit had started the High Wage Movement in 1922, and made demands of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association (HSPA), which spoke for the Islands’ sugar plantation. The main objective was to double the minimum wage from $1 a day to $2, demand a regulated eight-hour workday (instead of 10 to 12 hours), as well as overtime pay. Lastly, the High Wage Movement advocated for equal pay between men and women and collective bargaining rights.4

Adam Moore details in Colonial Legacies and Labor Export, that HSPA recruiting agents were required to obtain permits from the Bureau of Labor to set up offices in designated provinces. Signed labor contracts were mandated, and in 1915 labor agreements began including free transport back from Hawaii after the completion of a three-year contract. He goes on to mention that mechanisms to monitor labor conditions were also developed, most notably the position of resident labor commissioner based in Honolulu, which was established in 1923 in response to petitions by Filipino plantation workers (most likely from the High Wage Movement): “ultimately this did little to improve the conditions of workers as the commissioner, Cayetano Ligot, typically supported plantation owners in labor disputes. This is not surprising since Filipino government leaders remained under the ultimate supervision and control of the United States and were expected to act according to U.S. interests.”5

As Susan Evangelista narrates in her essay California’s Third Oriental Wave: A Sociohistorical Analysis that there was an attempt to keep Filipino laborers in Hawaii, as most were moving on to agricultural work in California: “soon after the Hanepepe Strike in 1924, Hermenegildo Cruz, head of the Department of Labor in Manila, made a special trip to Hawaii to reconcile the militants in the High Wage Movement to commissioner Ligot. There were no further labor troubles in the years that immediately followed, and Ligoťs position - the one real attempt of the Philippine government to protect its citizens in the U.S. atrophied. When Ligot left the position, he was not replaced.”6

I knew very little about my grandmother’s father or my grandmother growing up in Hawaii. Stories about him were often the stuff of legends. As a young man, he was in a Catholic seminary to study to be a priest, but later in life turned his back on Catholicism and became “Aglipayan” (a Philippine religion founded by a former bishop, Gregorio Agilpay, that broke off from the Catholic Church during the height of Catholic atrocities in the Philippines). He was also a Freemason and an avid reader. My mother mostly remembers her grandfather as a quiet man who enjoyed teaching her shortcuts to learning multiplication tables.

The interviews I conducted in Laoag, Ilocos Norte, in 2012, where he acted as governor between 1919 and 1922, did not tell me much about him either. His portrait was missing from the Governor’s Hall. It seemed his work as Acting Governor had not left an indelible mark on the city. Even the library that the City Hall records claimed he (Cayetano) opened and inaugurated in 1921 was left empty. They just moved to better and brighter facilities a year ago. I finally stumbled on the only surviving landmark I could find. It was a small street named “Ligot”, where the old Ligot family home had been.

iii. the act of weaving

The story began to evolve outside of the grandmother’s standing in for my contentious feelings about my own home town, Cebu, and instead began to ask the pertinent question of extraction in the guise of economy– how both people and raw materials were in states of perpetual trade within the colonial territories, how one’s existence hinges on an economic product, and how in this equation, the person and the raw good (sugar) were seen as tools of the state and no more. How does one weave a story of a personal displacement within a trans-diasporic movement of many displacements?

The first iteration of Untitled (Sakada) in 2012 was a testament to my grandmother’s contentious return to the Philippines and how displacement and translocation take on a different tone when taken from within the context of the return to the homeland, where one is “from”, disregarding that this “from” is constituted of more than geographical origins, and that “home” is as contested as “origin”.

It was only fitting that 10 years later, in 2022, I would return to this work, only this time invited to speculate on the artistic research within the framework of Cheryl I. Harris’ “Whiteness as Property.” The story began to evolve outside of the grandmother’s standing in for my contentious feelings about my own home town, Cebu, and instead began to ask the pertinent question of extraction in the guise of economy– how both people and raw materials were in states of perpetual trade within the colonial territories, how one’s existence hinges on an economic product, and how in this equation, the person and the raw good (sugar) were seen as tools of the state and no more. How does one weave a story of a personal displacement within a trans-diasporic movement of many displacements?

Anna Hoffner ex-Prvulovic*, curator of the Whiteness as Property exhibition, writes in her introduction that the exhibition project “inquires into the present relationship of theory and practice to the material beyond processes of racialized dispossession and starting at a juncture where desires for the ghostly converge with desires for language and signification. It is precisely here that language quickly comes under the general suspicion of being a disciplining instrument of description and communication, meaning that the abundance of desires and imaginings that strive to create a direct correspondence between things and their supposed statements must be examined. For although it appears that things are in possession of themselves, there are actually very concrete individuals who possess them and determine how they speak.”

She goes on to say that a different kind of voice is heard in the installation Untitled (Sakada), reminding us that the voice can never exist independently of signification and is always subject to relations of domination. Which voice evolves at the margins of colonial exploitation, in the dispossession of bodies and resources?7

The archives are proof that these voices did speak. They spoke through articles tallying the dead (“17 Dead in Strike Riot” reads of the headline of the Garden Island Newspaper on September 9, 1924), or through the stories passed on by the Filipino laborer who worked and lived on the Koloa, Makaweli, Kekaha, Lihue and McBryde Sugar Co. plantations, stories that hopefully pass on to their descendants, like my great-grandfather’s passed down to me. These voices, these bodies—the troves of stories we carry inside us.

The Garden Island Newspaper on September 9, 1924: “17 Dead in Strike Riot”. Photo by Daniel Hill

iv. the art work

The installation Untitled (Sakada) 2012/2022 weaves these intersecting narratives through family pictures, a video piece, a pressed LP record, and printed research material.

There are two vitrines in the installation. The first vitrine holds a mound of muscovado sugar from the Philippines. Muscovado is an unrefined (or raw) sugar obtained from the juice of the sugarcane by evaporating and draining off the molasses. Muscovado sugar contains impurities which render it dark brown and moist. In the same vitrine are also photographs taken (and perhaps developed) by Ligot of places in the Philippines. He was a hobby photographer and often took pictures of landscapes and people.

The second vitrine contains a family photo from Hawaii. One has Cayetano Ligot standing in the middle with a hat circa 1940s. The dedication on the back of the picture reads:

“To My Darling Juicy Fruit,

This may be late but…”

Also in the second vitrine is a book form of the report that he had crafted to the Hon. Leonard Wood. Governor-General of the Philippines on October 15, 1924, aptly named “Filipino Laborers in Hawaii”8 that reads:

His Excellency,

I have the honor to submit to your honor the following report covering my one year work (March 31, 1923 to March 31, 1924) in the territory of Hawaii in the capacity of Labor Commissioner.

Very Respectfully,

(signed) Cayetano Ligot

Resident Labor Commissioner.

The video in the installation juxtaposes footage from the 1941 American Time Magazine documentary series The March of Times and a series of family photos of my grandmother’s family and of my Lola (grandmother in Filipino), Gloria Ligot, in Hawaii as a child. As well as an article and images sourced from The Garden Island newspaper, September 9, 1924.

The first time I heard “Little Brown Gal” was when Lola played it for me on the piano. “It’s a hula dance," she said. Then she taught me how to move my hands (‘round the island) and hips to the music.

“It isn’t Waikiki

Nor Kamehameha’s folly

Nor the beach boys free

With their ho’omalimali

But it’s a little brown gal

In the little grass skirt

In the little grass shack

In Hawaii”

The original title of the song playing on the record is “It’s Just a Little Brown Gal in a Little Grass Skirt in a Little Grass Shack in Hawaii.” It was written by Don McDiarmid and Lee Wood in 1935. This is one of the four songs commonly used by Matson ships and Waikiki hotels to teach the hula to tourists in Hawaii. This version of “Little Brown Gal,” playing on an endless loop on vinyl in the installation, is interpreted by Genoa Leilani Keawe and her Hawaiians, an icon of Hawaiian music famous for her soaring and seemingly endless falsetto. She was born in Oahu in October 1918.

v. Gloria Ligot

My Lola, Gloria Ligot, moved to Hawaii when she was 3 years old. Her father had been assigned the post of Resident Labor Commissioner in Hawaii. He left for Hawaii in March 1923, shortly after my grandmother was born in Laoag, Ilocos Norte. She and her mother would later follow on a trans-pacific journey across the ocean on the same ship as many Sakadas heading to Hawaii.

As a child, I had never fully understood my Lola’s predicament of being in-between, not being fully Filipino, and never being Hawaiian (or American). She lived in the time when Hawaii and the Philippines were technically American territories. She married my grandfather when she was 23 years old and moved to his hometown in the Philippines, Cebu. This may have been the first time she had ever been back to the Philippines.

Lola never showed me pictures of herself as a child in Hawaii. My Uncle Sonny (a close family friend and her “little brother”) had to scan the pictures and send them to us, the grandchildren, so we could see them. I showed them to Lola again this last visit to the Philippines, and she chuckles about her parade “escort”, the tall boy tasked to walk by her side through the festivities. “He was a dreamboat,” she says. The original point of departure for Untitled (Sakada) was my grandmother’s immigrant experience.

In the cultural usage of the Filipino diaspora, balikbayan literally describes “balik” (return) and “bayan” (city), the return of Filipinos permanently living abroad as tourists. The term balikbayan denotes not only a changed perception of space but also a radically different concept of identity, which is defined by volatility instead of permanence, and thus not by which is generally associated with stability but with mobility. However, what the term balikbayan, this temporary return, does not mention, are the various forms this return can take.

Lola would often fly to Hawaii to visit her siblings. She was the only one who ever came to live in the Philippines. Surprisingly, so did her father after his retirement. Cayetano (Lolo Tano), who came to live with my grandmother and her family till his death in 1974. My only token of her return visits to Hawaii would be the occasional mumu (a Hawaiian house dress), lots of Hawaiian Host macadamia nut chocolates, and my favorite—a shirt that read “My grandmother went to Hawaii and all she got me was this lousy T-shirt”.

Gloria Ligot in Hawaii

Gloria Ligot in the parade