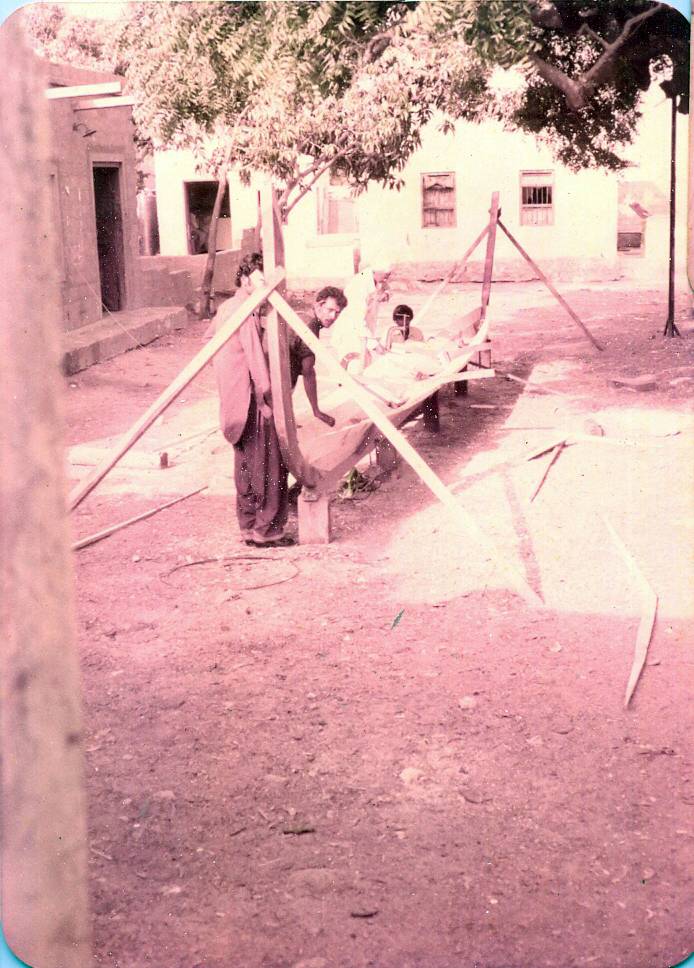

A view of Ibrahim Hyderi’s port in Karachi, Kashif’s workshop, and the ongoing construction of ‘Laanch’, 2023

Behzad Khosravi Noori is an artist, writer, educator, playground maker, and necromancer. His practice-based research includes films, installations, and archival studies. His works investigate histories from the Global South, labour and the means of production, and histories of political relationships that have existed as a counter narration to the east-west dichotomy during the Cold War and beyond.

Rooted in a study of the fishing economy – encompassing industrial fishing and indigenous craftsmanship – Seascape of Imagination, as this text and a future project, envisions the preparation and development of a revitalised economic structure within the fishing ports of the Indian Ocean. It delves deep into the intersection of resourcefulness, itinerancy, craftsmanship, and labour within the South Asian context, with a focal point at Ibrahim Hyderi port in Karachi. Through artistic research, Seascape of Imagination is an attempt to unravel the intricate ties between South Asian transnational craftmanship practice and the nuanced processes of decoration and labour, emphasising the boat engineering craftsmanship that survived colonial and nationalist modernity. A significant aspect of this project is challenging the prevailing modern distinctions between art and craft, especially when contextualising the act of painting as a decorative aspect of the shipbuilding done by members of the fishing community. It delves into craftsmanship in Karachi during both the colonial British reign known as the British Raj and subsequent postcolonial religion- nationalism after the 1947 partition to conduct an inquiry about Persian-Hindu shipbuilding technology during the golden age of Islamic thought. The text portrays a vivid picture of an imagined realm—a fleeting yet delightful glimpse into a utopian future, a momentary paradise of tangible accessibility, a brief utopia, a brieftopia.

Ibrahim Hyderi and the Shadow of Colonial Expansion and Modernization

Ibrahim Hyderi port is located southeast of Karachi, the capital of Sindh province in southern Pakistan. The port and surrounding area were, in part, created by British commercial and military expansion in the region during the nineteenth century.

In the aftermath of the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842), guided by East India Company directives, General Charles Napier, who had been promoted to Major General to oversee the British Indian Army stationed in the Bombay Presidency, was dispatched to the Sindh Province (Scinde) with the objective of suppressing the rebellion led by Muslim rulers who maintained hostility towards the British Indian Empire. Napier’s journey to the village of Karachi began through Kiamari, the port that served as the primary gateway for the British and subsequently evolved into Karachi’s principal maritime hub, a status it maintains to this day. He exceeded his responsibility, disobeyed the order, and conquered the province of Sindh in 1843. “You will yet be the glory of the East; would that I could come again to see you in your grandeur”, Napier wrote in his diary, possibly to justify his disobedience to the direct order to not conquer Sindh.

At the same time, the wandering armies of Alexander the Great, the Arab conquest of Sind, and the Moguls from the cities of the north influenced the activity around the many mouths of the Indus.

Karachi became the entrance point to the land from the Ocean, the closest port to the mainland of Europe and the empire, the Liverpool of the South, replacing older native ports, and was linked by rail to Hyderabad. As trade expanded, Karachi and Bombay became home to hundreds of merchants from Kachchh who moved west in search of profit. The immigration has never stopped and continues until today, making the point that the population of the city has become a myth.

In 2023, I spent nearly a year delving into the colonial archive at the British Library and Maritime Museum in London, exploring the East Indian Company records of Sindh and Karachi dating back to 1843, when General Napier invaded Sindh. In the African Asian Studies room at the British Library, I was sifting through century-old documents that had not been requested since their cataloguing. My inquiry unveiled the varied pronunciations of the city, which are known by names like Crochey, Krotchey Bay, Caranjee, Koratchey, Currackee, Kurrachee, and eventually Karachi.

The advent of industrial fishing contracts under the 1995 WTO and transnational trawlers, mainly Chinese, have dramatically altered the fishing landscape in recent years. Due to these changes, local fishermen are compelled to venture further into more profound and more turbulent waters, thus intensifying the masculinity of the profession and making it a considerably more challenging environment. As a result, as one participant poignantly remarked, “Women have been entirely alienated from the sea and its resources.”

Ibrahim Hyderi’s Fish Market (2023)

The historical significance of Ibrahim Hyderi remains elusive, even though people carry generational memories of the port. Despite an abundance of accessible documents, I couldn’t manage to find a single document under the name of Ibrahim Hyderi. In the mid-19th-century maps, the port’s location was covered under the city’s name, usually on the left button corner. The lack of documentation was partly due to geographical constraints—the port lacked the depth required to accommodate large vessels, making it insignificant to strategic interests of the British. Hence, they paid little heed to the indigenous fishing community that inhabited its shores. This neglect by the governing bodies continued after the partition and the establishment of the new nation of Pakistan on August 14, 1947.

In the quest for modernization, the Pakistani government enlisted Greek architect Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis to envision a modern facelift for the provincial capital in 1953-1959. This vision took shape as a new neighbourhood near the port, known as the Korangi district, was recognised as the city’s industrial section. Doxiadis’s concept of Ekistics (Science of Human Settlements) and Entopia (in place) was situated in close proximity to the Ibrahim Hyderi port, and it became the border between the old colonial district of the cantonment and the postcolonial modern Korangi district located on the southeast part of Malir district. In this ambitious urban redesign, the intrinsic values and practices of the indigenous fishing community were side-lined.

The absence of acknowledgement for the indigenous fishing community becomes evident when we examine the 1952 master plan, also known as the Greater Karachi Plan, put forth by the Swedish company Vattenbyggnatsbyrån. Initially outlined in their preliminary report from 1949, this plan laid the groundwork for the new capital city, emphasising industrialisation and economic development of the port’s capacity in alignment with evolving urban modernization. It again overlooked the vital role and needs of the indigenous fishing community. This oversight epitomises the broader challenges faced in postcolonial contexts where intersections of class, ethnicity, and gender play pivotal roles.

Women from Ibrahim Hyderi were deeply involved in open-sea fishing. However, based on my conversations with the women from the fishing community, the advent of industrial fishing contracts under the 1995 WTO and transnational trawlers, mainly Chinese, have dramatically altered the fishing landscape in recent years. Due to these changes, local fishermen are compelled to venture further into more profound and more turbulent waters, thus intensifying the masculinity of the profession and making it a considerably more challenging environment. As a result, as one participant poignantly remarked, “Women have been entirely alienated from the sea and its resources.” This shift has led many of these displaced women towards employment in the local textile factories in the nearby Korangi district or the rapidly expanding shrimp export processing industry– that capitalism has altered gender roles.

Historically, fisherwomen were at the forefront, undertaking tasks such as crafting fishing nets, accompanying the men into the expansive open sea, drying fish on islands, and supplying fresh water to the crews of vessels. With the inexorable march of time and societal shifts, these women have been marginalised, losing their traditional occupations and roles and subsequently finding themselves primarily confined to their homes.

At the same time, the notion of local economic practices devastated the port economy, too. Although, fishermen spend days and even weeks, out at deep sea, but, they often have to hand over most of the money they make from the catch to the boat owners.

In return, they receive a mere pittance for their labour-intensive efforts. The undeniable reality is that the inhabitants of the port find themselves in economic limbo without a sustainable solution to their financial predicaments. They are trapped in the relentless clutches of commercialisation and capitalism. Corporate fishing enterprises have now usurped what was once their traditional domain. The nuanced role of gender, particularly the diminishing roles of fisherwomen, remains a poignant reminder of the broader sociocultural implications of this transition.

The New Silk Road, a Neo-Liberal Historical Reenactment

In early May 2022, I began to find out more about the founding of the Chinese Port in Karachi.

The Chinese government built the new port in Karachi in close proximity to the old port of Karachi Keamari. The foundation of the port dates back to 1984, and the new structure began in 2005 to develop the region’s economic prosperity. The new port is part of the larger project, which is a reenactment of the historical Silk Road in Karachi, a city strategically built by the British right after the occupation of Sindh in 1843 and developed during The Second Anglo-Afghan War from 1878 to 1880 to suppress the Afghan rebellion in the north and simultaneously defend the Russian Empire during the Great Game.

In 2013, amidst the corridors of power in Beijing, a vision emerged—The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), or as it’s known domestically, the One Belt One Road, Yīdài Yīlù or OBOR/1B1R for brevity. This ambitious global infrastructure development strategy, supported by the Chinese government, aimed to extend its economic influence across more than 150 countries and international organisations. For Xi Jinping, who was newly elected, the BRI was more than just a policy; it was the cornerstone of his foreign strategy, encapsulating his vision of “Major Country Diplomacy” (大国外交). China sought to assert its growing power and stature on the world stage through the BRI. It assumed a leadership role in global affairs commensurate with its economic might, mimicking the American Marshall Plan, recognising the BRI’s potential to reshape geopolitics and international economics. In this global plan, Karachi was an essential location, as was Goader in Baluchistan province in Pakistan, with access to the Sea of Oman, the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Living in Karachi, the vast expanse of land can often make one overlook its intentional location. It’s easy to forget that this city is not just a bustling and even brutal urban centre but also a port intimately connected to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. You don’t truly feel the sea’s presence unless you reside nearby. And even when you are nearby, the vastness of the sea is somehow under the shadow of the monstrous colonial city. However access to the sea and ocean is essential in the current geo-political order.

Standing on the beach of Clifton in Karachi, looking at the port of China, I wondered if the past still echoes the present in Karachi – a colonial history to the post-colony present within one of the world’s most rapidly expanding metropolises. Looking at the Chinese port, I asked my friend Sameer, an independent journalist and environmental activist, to take me to any fishing community. And for the first time, we visited Ibrahim Hyderi ابراہیم حیدری, one of the oldest fishing ports in the Indian Ocean, as locals claim.

Sameer introduced me to Fisher Folk Forum, a local NGO concerned about the lives of fishermen in the port and the ecology and environmental issues around it. We discussed the port’s economy, the environmental catastrophe, the Chinese industrial fishing boats, and the sea. Soon after our meeting and discussion, I made a short film, an eight-minute journey into the sea and the myth of the sea. Although the footage in my film didn’t address any of these issues we discussed with the fisherfolk, it became a point of departure for the complexity of being a fisherman (Mahigir) in this context and the craftsmanship around it.

Kashif’s workshop at Ibrahim Hyderi, view from Laanch, 2023

Still from the film (work in progress) Hoora (working title), seen in the image are a group of fishermen repairing fishing nets at the Ibrahim Hyderi, 2021

The film’s narration attempts to combine the story of the sea and a mythical journey to China known as Arz al Ein ارض العین the eye of the earth in the old literature, the place where was the farthest land behind and beyond Mount Qaf where the distance between the earth and the sky is as a human height; the homelands of the Jins and fairies. In his journey, China was the furthest location that Egyptian prince Saif al-Mulūk سَيْف الْمُلُوْك voyaged to meet the love of his life, a fairy named Badīʿ al-Jamāl وَبَدِيْع الْجَمَال, whom he dreamed about. He was in love with a fairy. But the fairy wasn’t in China.

Have you ever loved a fairy? And gone and search for them?

Taimoor Shaheed, the narrator and co-writer of the film, narrates:

Have you seen a sea without a crane?

What is a crane? Is it a bird? Or is it a dinosaur?

Was the ship of the prince like this giant ship?

Where do these ships take you?

Can a fairy tale be told on a ship like this?

Badīʿ al-Jamāl

The core focus of the project will be a collaboration with the fishing community that revolves around the craftsmanship in the port of Ibrahim Hyderi. This future project delves deeply into these layers, foregrounding local artisans’ intrinsic artistry and expertise.

The heart of the project—the boat’s construction—will unfold in collaboration with Kashif Faisal and Qasim Ali in their workshop. Kashif Faisal and Qasim Ali, both young Sindhi boatmakers, have inherited the craftsmanship and technical intricacies of production from their parents. They possess deep knowledge of the fishing community’s environment and economy. The boat will be called Badīʿ al-Jamāl بَدِيْع الْجَمَال, the fairy from the north, the Magnificence Beauty. It will feature a custom-designed flag for the ship and will be decorated with illustrated storytelling inspired by the myth of the sea.

The future collaboration with Kashif and Qasim is a deliberate choice that develops the project on multiple levels. By situating the construction process in their workshop, we’re not merely leasing space and skilled labour; we’re embedding the project within a context steeped in generations of indigenous boat-making expertise.

From a family album, ‘Crafting a ‘Hoori’ boat in Wahidwani Mahalla, Ibrahim Hyderi, during the 1970s

Kashif Faisal’s workshop, Ibrahim Hyderi’s port, Ongoing construction of a Laanch, Photo by the Author, 2022

Kashif and Qasim’s workshop itself will be a living archive, a brieftopian place bearing the tracks of skilled hands and years of inherited experiences – a space where wood meets tradition and where each tool has a story. This collaboration also affords an intimate look into the actual process of indigenous boat-making, complete with the techniques, materials, and cultural significance and rituals that Kashif and Qasim bring to the table from the legacy of Persian-Hindu shipbuilding.

Among the spectrum of boat-building practices, two main types, the Hoora and Laanch, have been crafted with deep-sea navigation. Kashif’s idea, based on the local fishing economies, points towards the Hoora or a smaller Laanch as the most fitting choice for our project.

Uncovering the origins of the Hoora and Laanch presents a somewhat elusive quest. While the specific artisan or community responsible for their initial design remains a mystery, local folklore suggests that the Hoora may have its roots in an indigenous community. The earliest documented evidence, featuring depictions of the Hoora and Laanch, dates back to 1857 and is preserved in a drawing housed within the British Library archive. In the local vernacular, the term “Hoora” translates to “male” or “giant,” a nod to the boat’s impressive size, measuring approximately 20 metres in length. These vessels are equipped with specialised fishing nets meticulously crafted to capture specific types of fish, including Katra, Bholo, Thokri, and Latho Bhan.

Building the boat will take fifteen months. The workshop will be a place of events and conversation, inviting guests and locals to participate in the shipbuilding process and listen to stories from the fishing community. The aim of the workshops will be to investigate the port’s memory through the ambulant archive and photographs within the family albums against the abyss of oblivion of the face business of history.

The scant documentation in the form of a 1956 article1 highlighted some fishing boats in the port of Ibrahim Hyderi but missed a deeper engagement with the craftsmanship techniques — mainly carpentry and painting. I plan to focus on documenting the boat-building process, as it doesn’t follow any drawing or blueprint. Instead, knowledge has been disseminated chest to chest from one craftsman to another. Upon the project’s completion, the fishing boat, the Badīʿ al-Jamāl, will be returned to the community, signifying collective ownership. It is an economic initiative and a reaffirmation of shared community values. Badīʿ al-Jamāl explores a potential economic model centred on the collective ownership by fisherwomen, once again bridging craftsmanship with both class and gender considerations.

Brieftopia is a place where a fairy tale can be told.

I grapple with the possibility that my actions might unconsciously align with those of a colonial agent, perpetuating the cycle of documentation and relegating it to the depths of ethnographic archives. Could the creation of ostensive archives and art be likened to a form of preservation akin to killing and taxidermy? For whom am I arting?

This text and the project are a proposal for artistic exploration – a brief moment of delightful imagination— a brieftopia, a glimpse into a potential future (boat) that is both accessible and tangible.

While the initial plan outlines the construction process, it leaves me questioning my approach. I grapple with the possibility that my actions might unconsciously align with those of a colonial agent, perpetuating the cycle of documentation and relegating it to the depths of ethnographic archives. Could the creation of ostensive archives and art be likened to a form of preservation akin to killing and taxidermy? For whom am I arting?

“Brieftopia” represents a moment of imaginative fluidity within the confines of our present environment and the temporality of time. My act of writing here is a “brieftopia,” a brief moment in time. Imagining a tangible future provides a temporary refuge, helping me navigate the trials of existence. A “brieftopia” is not merely a disconnected realm of sub-political consciousness divorced from the realities of the workplace. It is a brief intermezzo where our minds embark on an imaginary journey, interweaving through the fabric of the real world while momentarily escaping its constraints.

There’s a saying among fishermen: “The good captain is the better storyteller.” After enduring days and weeks navigating the treacherous depths of the sea, weary fishermen gather as they prepare to return home. The captain, guided by the stars to chart the course homeward, regales them with tales and legends, serenading them with epic stories. Is the journey of Saif al-Mulūk and his odyssey to the sea one of them?

But does this ritual bear amidst the existential threats faced by fishing communities—ranging from climate injustice to the violation of industrial fishing, notably by Chinese vessels, despoiling the sea before their very eyes? Can an imaginative artistic project embodied by a boat offer salvation amid the mafia’s economic operation and the life depth of the fishermen? What role does art play in shouldering the responsibility towards the fishing community and their craft? Is there an ethical imperative in this relationship?

The wishful thinking, the brieftopia, a moment of emancipatory imagination, the seascape of imagination suffers from uncertainty and insecurity; a melancholic structure of feeling which is not only about loss and eclipse but also harbours utopian impulse openings for practices of solidarity, creativity, and unalienated forms of social life.

With a particular focus on critically analysing the connection between the capitalist motives driving transnational industrial fishing and the perpetuation of masculine and patriarchal social dynamics, I aim to examine how industrialised economic activities, such as transnational fishing and mainly Chinese trawlers, can influence and reinforce traditional gender roles and societal power dynamics.

The landscape of imagination, with its brieftopian wishful thinking, can bring women back to the sea as a gesture of the tangibility of the past in its future.

The wishful thinking, the brieftopia, a moment of emancipatory imagination, the seascape of imagination suffers from uncertainty and insecurity; a melancholic structure of feeling which is not only about loss and eclipse but also harbours utopian impulse openings for practices of solidarity, creativity, and unalienated forms of social life.

As I envision it, the future boat is a place for events and communal gatherings. It represents an imagined space capable of embodying the notion of a promised land. It emerges as the quintessential backdrop for fishing, storytelling, and social gatherings—a fleeting place, a “brieftopia,” destined to conclude but not to fade into obscurity – it persists perpetually, reigniting the longing for renewal until a new narrative unfolds.

Karachi’s Ibrahim Hyderi port: Kashif’s workshop with a new ‘Laanch’ under construction in the background and an old ‘Hoori’ in the foreground, 2024

Kashif’s workshop at Karachi’s Ibrahim Hyderi port, where a ‘Hoora’ is under construction. 2024

Two ‘Laanch’ under construction at Karachi’s Ibrahim Hyderi port, 2023

Kashif’s workshop at Karachi’s Ibrahim Hyderi port. A ‘Hoora’ is under construction, 2024