Tuomas A. Laitinen is an artist who works with video, sound, glass, and chemical processes to explore the entanglements of multispecies coexistence. Laitinen composes situations and installations that inquire into the porous interconnectedness of language, body, and matter within morphing ecosystems. He received the Fine Arts Academy of Finland award in 2013, the AVEK prize for media arts in 2021, and is nominated for the 2023 Ars Fennica prize.

I met with Maija in her career-spanning exhibition Roadside Narratives at Taidehalli in Helsinki. We talked about her artistic practice, which is conceptually rich but, at the same time, filled with gentle curiosity about the difficult questions facing the planet and its inhabitants. Maija’s approach is documentary but does not claim any universal truths. Instead, it often offers moments of shifts in the perception of reality, creating both poetic and humorous situations. The work opens the possibility of shapeshifting from documentary into multimodal and granular fiction. As such, it presents a timely contact zone for understanding situations where the ghosts of facts and knowledge create strange, fictitious perspectives.

TUOMAS: When we met at your exhibition for this interview, we discussed your tendency to notice things that happen while you are working on a film, and these things can eventually become an important part of the work. Realising that something is not possible in a specific situation presents a possibility for something else to happen. And this requires paying close attention to details during the working process. Can you give me an example of these situations?

MAIJA: As I work with documentary subjects, unexpected things can happen, and I think it is one of the most important areas of this work to recognise if the unexpected is something I should ignore or something I should look at. I also don’t have any logical answer or explanation on how to see the difference. But if you choose to ignore something, you will most likely never become aware of what you have lost.

Sometimes I have made the right decision. For instance, during the shooting of On Destruction and Preservation on the arctic island of Svalbard in 2017, it happened that in the middle of the arctic winter, on the day of my arrival, there started a continuous rain lasting for almost a week. Most of the snow melted, and it became impossible to reach the closed coal mine at the destination I had originally planned to go to film at. It was +7 Celsius, as the normal average temperature in February should have been -18. There I stood in this saddest possible rain in this end-of-the-world landscape and did not know what to do.

I was told I should attend a sightseeing tour by a local taxi driver, Finn, which I thought sounded very uninteresting. But as the lady at the local tourist information office just kept saying, “You really should go on the tour,” I finally gave up. Her way of saying it and trying to convince me to take part in this simple tourist trip felt somehow magical. After 10 minutes of the tour, I knew I had the film I wanted to make here. I was really happy that Finn agreed to be filmed and that the key scene of the film became real. I believe the outcome is so much better than the original plan could have ever been.

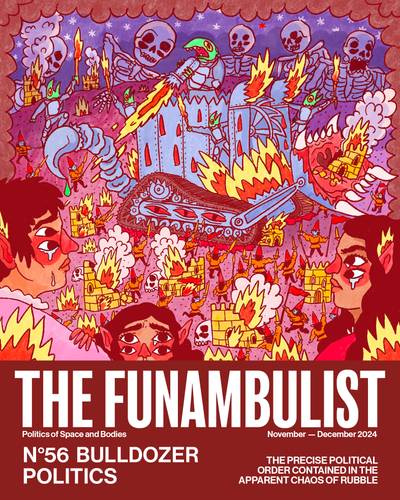

Maija Blåfield, Roadside Narratives, 2023.

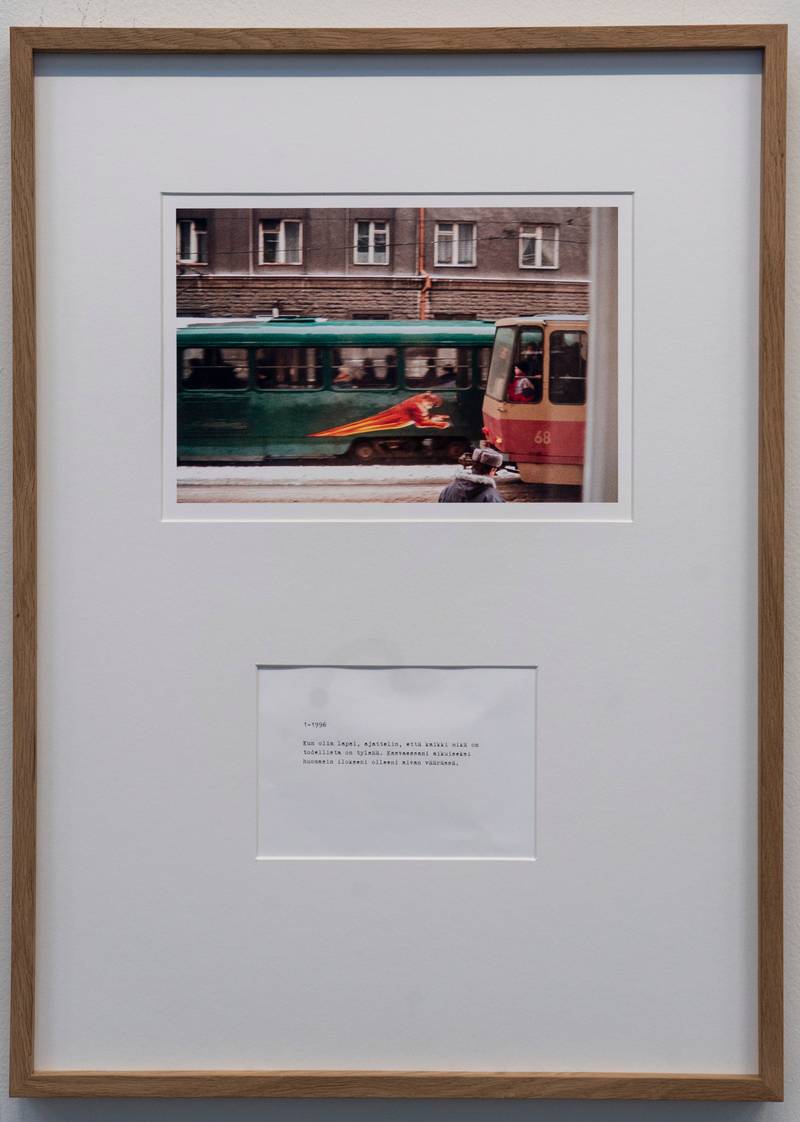

Maija Blåfield, Roadside Narratives, 2023.

I am interested in how you plan and structure your work process. Do you read a lot during the research phase? And if you do, what readings have influenced your recent works?

It depends on the project. While in the very beginning of the process of making the film The Fantastic (2020), I read Tzvetan Todorov’s The Fantastic and felt strong similarities in how he defined the process of encountering something previously unfamiliar and how it changes or does not change our perception of reality. The process of making the film was slow and complicated and took place over six years. The Fantastic was the working title of the film but ended up being the final one, as I just could not find any title that could have been more accurate for this work.

Also, while making Scenic View, I read a lot; for instance, Metsä meidän jälkeemme by Pekka Juntti, Anssi Jokiranta, Anna Ruohonen, and Jenni Räinä was important.

I looked at the Roadside Narratives photo/text series in a non-linear way, making connections as I wandered in the exhibition space. How did you start to put these images together?

I always save every picture I take, despite how underexposed or blurry it is. Roadside Narratives includes pictures I have taken during almost three decades and additionally one picture from my childhood—a picture from the first film roll I ever exposed.

I mostly used simple cameras like pocket-size Rollei or later digital compact cameras, which were easy to carry everywhere. I like cameras that leave the question of technical quality aside and concentrate on the content of the pictures. The pictures are combined with the texts I have written and the dates the pictures were taken.

My relationship with photography is complex; at the same time as I see the importance of these pictures, I also feel they are some sort of burden. Humans take billions of photographs daily, which no one ever has time to look at. I feel that the era of photography and photographic art has reached the point of inflation and has made itself somewhat unnecessary. But at the same time, I am very aware that my own past would be different if I had not documented it, as would be my present time as well—the reality where I live. Roadside Narratives is built from this material.

I went through the pictures chronologically, starting with the negatives from the mid-nineties and continuing from the archives, where I have stored all the digital pictures since abandoning the film around 2005. Very slowly, I started to see what was meaningful in this material. In most cases, I chose pictures that I had not originally intended to take. For instance, one taken in Tallinn in 1996 from the window of a student hostel is probably the best picture I ever took. I wanted to take a picture of a tram passing by, but coincidentally, at the moment of pressing the shutter, another tram appeared from the opposite direction. A magical encounter between a small boy on one tram and a huge picture of a tiger on another one was created.

At some point, I also realized that all the pictures I chose were travel pictures in one way or another. That was very confusing, but I decided to stick to that, and so the series of Roadside Narratives was created. In a way, I see this work as a series of scenes from a documentary road movie. The moments created by the texts and photographs are revelations where the ordinary suddenly disappears, and the magic behind it is revealed for a short moment to the viewer.

Central to your work Scenic View is how the perception of the environment is constructed. In this work, the reality is exaggeratedly manufactured, mimicking how wildlife documentaries present various life forms. These documentaries are often staged to create a narrative of constant struggle, aiming for resolutions. The viewer does not see what is happening behind the scenes but only what the filmmaker wants them to see. This film shifts into a weird sci-fi mode to emphasise this interpretation. The unexpected changes in the forest remind me of Jeff VanderMeer’s book Annihilation as well as Tarkovsky’s Stalker (and the book it was based on). In both of these works, there is a zone that is undergoing bewildering ecological transitions and mutations. This video work has a slightly different tone from your previous works. The human presence is felt more in traces than in front of the camera. How did you start to imagine it?

In the beginning, I wanted to do something different for a change and got interested in nature documentaries and nature photography. Their process differs greatly from my usual one, so I decided to practice wildlife and landscape cinematography and see what would follow. The starting point was how humans tend to look at the landscape. Our perception is connected to our human culture’s history; while watching a landscape, we see it through the history of landscape painting. That way, our perception is based on a misunderstanding, as we, in most cases, do not look at the ecosystem of the landscape but instead follow the behaviour that is typical of the human species and look at the landscape as some sort of picture. That is why misunderstanding and perception are the focus of this film. I chose to create a fictional scene with imaginative nature phenomena in order to make this misperception visible. There are also horror film elements and atmospheres present in the film. I chose that because I see all the nature documentaries of our time as horror movies in a way, due to the ecocatastrophe we are living in.

Maija Blåfield, Scenic View, 2023, Kunsthalle Helsinki

Maija Blåfield, Scenic View, 2023, Kunsthalle Helsinki

There is a tendency to “ruin romanticism” in relation to abandoned places. In the video, the shift to the city begins from the bear observation booth, and then we find ourselves in Detroit, during which the voice-over is giving information on the species that are taking over the human-built environment. Detroit is one of those over-photographed cities where an entanglement of social injustices and the collapse of the industry have created a quickly deteriorating environment. What made you want to film in this particular city?

I quote myself from Roadside Narratives:

I like places where all the pictures have already been taken.

I can be sure that every view and moment or

the handkerchief on the pavement beautifully crumpled by the wind

is already safely recorded, on someone else's camera,

and I never need to look at those pictures.

But despite these thoughts, I also find these over-documented locations interesting. The documentation not only preserves but also changes how we perceive and look at the place - and sometimes in destructive ways. I felt quite uneasy in Detroit in the middle of all these abandoned and deteriorated homes, which had become something cool for the urban explorer tourists. As I was visiting the area for the Ann Arbor Film Festival nearby, I wanted to spend some time in Detroit and see if I could film nature instead of the city itself. The Detroit scene in Scenic View shows the feral gardens as a young forest growing and taking over the abandoned human infrastructure.

When we discussed earlier, you said that you want to approach complex matters in your work, but at the same time, you are aware that sometimes a linguistically defined “subject” of the work becomes a trap. And often, you need that to get funding and to give a façade for the work. Words create worlds, and it is sometimes difficult to find the right worldmaking process by means of description. When there is a mention of North Korea in a text about your work, The Fantastic, it is often presumed in public discourse that the work is about North Korea. In this case, it feels far from the truth. And, of course, saying that this work is about reality can feel a bit general in some situations. I think it’s great that an artist works as this filter in the sense of both focusing and widening the experience of a given situation. How do you navigate the pressures between a particular “subject” and what you actually want to convey with your artwork?

I was surprised how well The Fantastic was received. Of course, it is impossible to avoid the North Korean presence completely, but I was really happy that the audience received so well what was meaningful in this film. The film is built on the interviews I conducted with North Korean refugees living in South Korea about the illegal foreign fiction films they had watched in their old home country. So, the film tells more about our reality in the Western world and looks at how it was perceived by people whose only access to it was through mainstream fiction films instead of the news, books, or the internet. At the beginning of the editing process, I even tried to cut out the sentences that revealed the interviewees’ home country, but it turned out to be impossible.

The film raises the question of how reality is defined and what we wish to believe in. I wanted to reverse the set-up where Westerners are peeping in on the everyday life of the closed-off state. In this film, it is the North Koreans who direct their curiosity to the outside world and imagine what life in Western countries is like. I used documentary footage I had filmed in North Korea, which was made unrecognisable with analog and digital visual effects. The pictures disappeared in front of the viewers’ eyes before they had proper time to look at them. I think this was one of the key ways to avoid voyeurism.