Photo by Akshay Mahajan

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

Challenging the notion of the singularity of meaning and traversing the zones of fidelity and accuracy of an image, Tanvi Mishra switched to image-making after pursuing an economics degree, realising that the issues that interested her in the social sciences, like policy-making and social justice, were more imaginatively possible through image-making. Our conversation follows her keynote titled Translational / Transnational : world-building beyond bordered identities for the Out of the Metropolis seminar Artists and Curators Working Together: How and With Whom? organised at The Finnish Museum of Photography in mid-February.

VS: How can we effectively understand the impact of images on our socio-political or cultural realities when we consume an inundated stream of images and our attention jumps from one image to the next?

TM: Many of us are aware of the relationship between photography and imperial history. Westerners—most often the white man—went to parts of the world other than their own to document the people and lands. And so, in essence, the medium also has a patriarchal history. We can see it as having been an extractivist kind of media. To move away from that, we have to develop our own philosophy of what we associate with the image and what we want from it. For example, what is happening in Gaza may be far away from us, but it is stirring different things in different people. How do we locate our responses as distinct from what has been done in the past? As citizens, we have a responsibility to respond to the images coming from there. How do we take that to inform the cultural work we wish to do? Practically, how should somebody go about doing this? There isn’t a formula, but perhaps the responses that will be more meaningful are the ones that will be rooted in the politics we have, as citizens, of engaging with the world. If these politics are liberatory in nature and can imagine a future that is premised in justice and care for everyone, then our response may be useful to the discourse. After all, if artists do not build this imagination for the future, who will?

Good places images coming out of Gaza right now as an indicator of what awaits us in the future. For her, there is no such thing as desensitisation; there is a point of too much sensitization, which she refers to as ‘compassion fatigue,’ which is perhaps a more fitting term. I would not equate this state to being immune, but quite the opposite. Good says that the images coming out are not of the past, of an ‘aftermath,’ where we mourn or recover. She says that if we see them not just as a witnessing of the present moment but as a witnessing of future violence, a harbinger of what is to come, that can perhaps make us reckon with the urgency—and responsibility—to look at them.

The other thing I keep thinking about and don’t have an answer to is what this inundated stream of images does to us. There’s a conversation between Alice Zoo and Dr Jennifer Good called Witnessing Future Violence, where Good places images coming out of Gaza right now as an indicator of what awaits us in the future. For her, there is no such thing as desensitisation; there is a point of too much sensitization, which she refers to as ‘compassion fatigue,’ which is perhaps a more fitting term. I would not equate this state to being immune, but quite the opposite. Good says that the images coming out are not of the past, of an ‘aftermath,’ where we mourn or recover. She says that if we see them not just as a witnessing of the present moment but as a witnessing of future violence, a harbinger of what is to come, that can perhaps make us reckon with the urgency—and responsibility—to look at them.

You’re interested in the intersection of the image with politics, culture and society. When and how did you arrive at this understanding?

Our politics keep evolving, right? Although I always attribute the reckoning with my own identity and framing of my positionality within a larger politics to my time in The Caravan, I would say that, retrospectively, the political frameworks of my practice were being shaped at a subconscious level well before that.

I joined PIX in 2011, and we had the opportunity to visit countries in the South Asian region to research image-makers towards formulating an archive of contemporary photography in the area. Building this archive was essential to trace the role of visual culture in recording the societal history of the region. The work also feels urgent now because, looking back, most of the photographic references that are accessible widely would emerge from the Western canon.

The interactions we had during these visits, for example, in Iran, showed that artists were finding ways to make political work by circumventing or maneuvering around restrictions in ingenious ways that ultimately led to a thriving cultural scene. That was one of the first few instances when I began to acknowledge the image as a broad, intangible thing that can be manipulated to serve one’s own end.

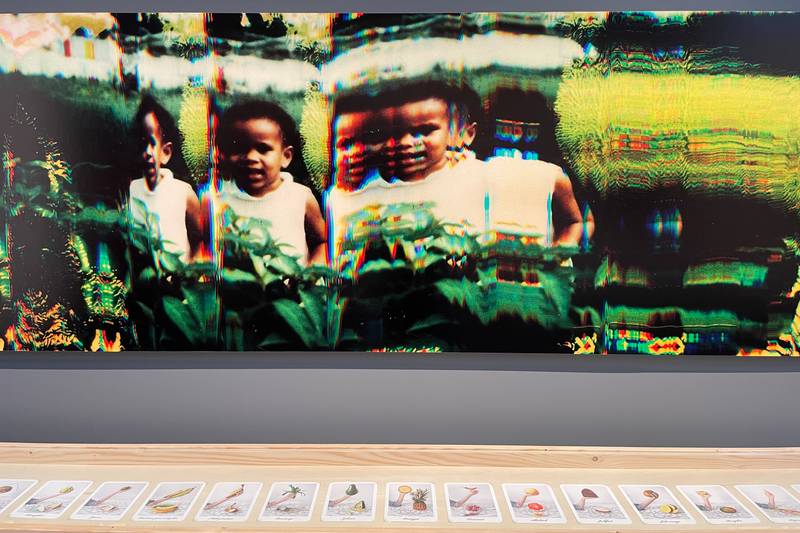

I also think about contradictions and self-criticality, and what excites me in photography is the constant dissonance within the politics of visibility. We want to show what is happening through our lens and language while also practicing the politics of refusal. It is a question that I have been more vigorously exploring since working with Samantha Box, who reappropriates colonial representations of the Caribbean. She talks about how we, as a previously colonised people, never really had agency over how we were photographed – and the idea that while we may wish to direct our own representations now, we may also not want to visibilised, or may wish to decide the terms of how much, if at all. To say that we do not want visibility is also liberatory politics.

So, the constant tussle with photography for me is that it keeps trying to show things. This ties into my interest of working with ideas and artists that engage with themes that are seemingly not visual, let’s say, sexual violence, bureaucratic systems, patriarchy, etc. I want to explore this a lot more because while our interventions with archives, as in the acts of bringing histories to light that haven’t been seen before, is critical work in many contexts, it can also easily trap us into the idea that we have to show everything to make people believe it.

Installation view of Constructions, part of the series ‘Caribbean Dreams’ by Samantha Box, exhibited as part of ‘Moving Definitions—an invitation to re-view’ at the Louis Roederer Discovery Award 2023 at Rencontres D’ Arles | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra

Installation view of Fracture and Flashcards, part of the series ‘Caribbean Dreams’ by Samantha Box, exhibited as part of ‘Moving Definitions—an invitation to re-view’ at the Louis Roederer Discovery Award 2023 at Rencontres D’ Arles | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra

We, as a previously colonised people, never really had agency over how we were photographed – and the idea that while we may wish to direct our own representations now, we may also not want to visibilised, or may wish to decide the terms of how much, if at all. To say that we do not want visibility is also liberatory politics.

How has collaborative working shaped the theoretical and conceptual frameworks of your work as a curator?

I’ve never seen myself work in isolation. For over a decade, most of my curatorial work has been within a team. When I joined PIX, I had no previous institutional learning in curation or photo-editing. We learned by doing. Rahaab Allana, founding editor of PIX, works as a curator in an archive of 19th-century photography, and I was working as a photographer at the time, so I brought in a practitioner’s knowledge. The team was also constantly evolving, with various people from different knowledge systems joining for different durations, ranging from photographers and collectives to those with a background in publishing or design with an interest in lens-based work.

When I joined The Caravan in 2017, I was among a group of colleagues reflecting on culture, politics, and society through the narrative form of text. I was suddenly outside of the photo/art world, not just from a working environment perspective but also in terms of audience. The Caravan’s emphasis on thinking critically about authorship and reiterating the value of underrepresented caste and regional perspectives in media, played a significant role in shaping my ethical and philosophical approach to curatorial practice. I learnt a lot from my peers at The Caravan, from their way of thinking through narrative, what they were reading, and how they constructed arguments.

When I quit The Caravan, I curated the BredaPhoto Biennial (2022), a co-curation among five people, which was interesting because there was also some friction. Three of us from the Global South–Mohamed Somji, who is a Tanzanian of Indian origin, and lives and works in the Emirates, and Denise Camargo, a curator from Brazil–working with two Dutch curators, Fleur van Muiswinkel, the director of the festival, and Reinout van den Bergh, who had been the curator of BredaPhoto since 2006. It wasn’t as if the three of us from the Global South agreed on everything either, and that heterogeneity was crucial to us having generative conversations rather than one of us offering a token representation. The frictions helped articulate how I place my interest, and interpretation, of the image in relation to what is happening in the world.

I certainly don’t see myself as a curatorial figure handing out some directives. The Les Rencontres d’Arles exhibition (2023) has been one of the few singular curatorial exercises I have done [for, e.g. while I was invited as a guest curator to Photo Kathmandu in 2016, I was always in dialogue with the larger photo circle team].

The way I see it is that at the Rencontres also, I was thinking along with the artists. What one artist told me informed my way of thinking, which could change my whole perception of the show, which I would then take as a proposition to the other artists. Usually, when you curate, you come up with a theme and invite artists whose work aligns. For the Discovery Award at the Rencontres, we received 400 applications without adhering to any theme, and the mandate for us was to select ten submissions and find a way to stitch the works into a cohesive show. Initially, I felt I may be imposing a reading or forcing connections between seemingly disparate works. I didn’t wish to make a holistic or limiting thesis. And so, I took one of the works—Philippe Calia’s—as a trigger; and structured the exhibition so as to look at the rest of the artists as responding to that trigger. Calia’s work looks at the Indian museum as a postcolonial institution, but it is also a commentary on how we read images through the dual tenets of personal memory and the artifice of viewing. And that eventually became the premise for the whole show.

How do we define radicality? What is the result of a more ‘equitable’ representation? It is important to reflect on the kind of politics we espouse or the ideas we foreground through inclusion and how we can constantly reinforce that notion of provocation—seen as a possible anathema to mainstream rhetoric—instead of ticking boxes with the inclusion of a certain person from a certain place [or identity marker of choice] to fulfil some representational utopia.

When entering an exhibition-building process in an institution or conversing with an artist you’re working with, do you have a key focus, theoretically, politically or conceptually, on what you must get out of this project?

Rarely, in my interaction with artists, do I meet them with preconceived ideas. I may have certain lines of interest that I wish to explore, sure, but I like to keep the space open for surprises. Like any regular human relationship, different definitions of closeness develop when working with artists. The trajectories of these kinships determine how the artists’ work manifests, shaped both by how much trust is shared and what they wish to foreground in their work.

As a curator, one engages with artists on one end and institutions on the other. The institutional end can carry its own frictions at times. In BredaPhoto, it was important for me to have works that didn’t conform to the training within the Western photographic canon. For example, Rajyashri Goody’s series Eat with Great Delight comes from a personal archive; the images in her work with the recipe-poems serve as a portal—for dialogue and introspection. You can appreciate the image for its aesthetic value, sure, but that’s not necessarily the point of the work. Her work received some resistance as we wrestled the final curatorial list, ironically not that it touched on the theme of caste, but because it did not fit into typical definitions of “good photography”. This resistance intrigued me, and I wished to incorporate this feeling curatorially, particularly in a biennale of photography. I think that making room for these provocations—not from a sensationalist point of view, but to allow for contradictions—is something I try to have within my curatorial projects.

At the Rencontres show, with their invitation to me as their first non-European curator, it felt like it was a significant moment. And then I thought, okay, what can we do that feels like it’s not just another year? I decided to foreground representation as a selection methodology, conceiving a show where 90% of artists identified with the Global South. Although I wanted majority representation, as opposed to the usual token inclusion, I didn’t want the exhibition to be reduced to being viewed through the limiting metric of a “global south show,” but for it to have a larger thesis for the audience to engage with.

Installation view of Eat With Great Delight exhibited as part of ‘Theatre of Dreams’ at BredaPhoto 2022 | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra

From the series Eat With Great Delight by Rajyashri Goody, 2018 | Courtesy of the artist

Operating from a sense of awareness is helpful, and I agree with the importance of representation, but what questions can be pursued after that?

Representation is not the end goal—instead, the real question is, whose voices do we want to engage with?

Now, if we look at the Hindu diaspora abroad that is wreaking havoc as one of the main funders of the Hindu right-wing agenda back home, can we simply look at it representationally and have some of those voices foregrounded in a curatorial endeavour? They are Indians, but, for example, how do they think about Kashmir? Now, if you’re going to bring that same binary and mainstream rhetoric of Kashmir as paradise versus conflict zone, I’m not interested in giving it a platform.

How do we define radicality? What is the result of a more ‘equitable’ representation? It is important to reflect on the kind of politics we espouse or the ideas we foreground through inclusion and how we can constantly reinforce that notion of provocation—seen as a possible anathema to mainstream rhetoric—instead of ticking boxes with the inclusion of a certain person from a certain place [or identity marker of choice] to fulfil some representational utopia.

I am interested in the possibility of heterogeneous dialogue across our worlds. For example, let’s take Vishal Kumaraswamy’s work within the Rencontres show. In articulating the grief—individual and communal—resulting from institutionalized violence and death in the Dalit community, Kumaraswamy works with generative imaging, using photogrammetry and 3D modelling. What he’s proposing formally is particularly relevant because he is rejecting the photographic representation of the body, particularly the Dalit body, and instead producing work that serves as an archive of rituals and practices seen as community heirlooms. When it was presented at Rencontres d’Arlessome people responded by saying, “This is not photography”; “It’s not being made with a camera.” For me, this is a redundant conversation. Would I make images using his visual method? I’m not sure. But I am interested when the decisions about form are dictated by the thematic, and in this case the radical reimagining of the Dalit body on an anti-caste framework. So again, his representation in the exhibition becomes meaningful in that way. For that work to sit beside classical documentary work, where they both espouse radical politics but in entirely different forms, creates seemingly conflicting positions, which is quite exciting.

In that show, while we had Kumaraswamy’s still and moving images, there were also sculptures, archives, cyanotypes on tortillas, as well as Philippe Calia’s work that was straightforward documentation. Some people were a bit confused because they said to me, We can’t tell what your taste is. Perhaps they meant it as an insult, but I took it otherwise.

At the Rencontres, I titled the show Moving Definitions: An Invitation to Re-View because, even though the artists were looking at familiar subjects, whether gender, patriarchy, the post-colonial institution of the museum, or stereotyping of Asian people, their ways of seeing (and showing) these thematics were novel.

![From the series *ಮರಣ Marana [Demise]*, photogrammetry and direction by Vishal Kumaraswamy, generative image processing by Emilia Trevisani, 2022-2023 | Courtesy of the artist](/images/sk42m6nit8ivwc7slhc4-800w.jpeg)

![From the series *ಮರಣ Marana [Demise]*, photogrammetry and direction by Vishal Kumaraswamy, generative image processing by Emilia Trevisani, 2022-2023 | Courtesy of the artist](/images/sk42m6nit8ivwc7slhc4-lqip.webp)

From the series ಮರಣ Marana [Demise], photogrammetry and direction by Vishal Kumaraswamy, generative image processing by Emilia Trevisani, 2022-2023 | Courtesy of the artist

![Installation view of *ಮರಣ Marana [Demise]* by Vishal Kumaraswamy exhibited as part of ‘Moving Definitions—an invitation to re-view’ at the Louis Roederer Discovery Award 2023 at Rencontres D’ Arles | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra](/images/vj8d396ms2soizp7pb1o-800w.jpeg)

![Installation view of *ಮರಣ Marana [Demise]* by Vishal Kumaraswamy exhibited as part of ‘Moving Definitions—an invitation to re-view’ at the Louis Roederer Discovery Award 2023 at Rencontres D’ Arles | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra](/images/vj8d396ms2soizp7pb1o-lqip.webp)

Installation view of ಮರಣ Marana [Demise] by Vishal Kumaraswamy exhibited as part of ‘Moving Definitions—an invitation to re-view’ at the Louis Roederer Discovery Award 2023 at Rencontres D’ Arles | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra

There is also a lot of focus on the fact that I can only represent or present my lived experience. With this premise, I want to delve further into the insider-outsider question. One often hears the word ‘outsider’ as one with a double gaze, and the insider is usually perceived as holding a privilege. How do you navigate these ideas?

There is always the question of who the ideal insider is. Whose story am I allowed to share? Where will I not be considered an outsider? If you narrow it down to only lived experience, we may eventually only be left with autobiographical work. Instead, I’d like to tell the story of somebody in a different reality than me, but am I allowed to tell that story? The answer may lie in the intersection of our lived experience with our politics of engaging with society and culture. For example, right now in Gaza, there’s no entry for other journalists, but we all inhabit different positions in the ecosystem of images. And it is our responsibility as artists to keep them in circulation beyond the limited cycles of news and social media. Just because I was not born in the SWANA region and it is not my immediate reality, am I not supposed to talk about it? That’s where the question “What is my identity?” arises. Just like we don’t want to pigeonhole ourselves by a singular metric—be it regional, national, caste, gender, etc—we would also not wish to pigeonhole others.

Someone like Alana Hunt, an artist based in Australia, has worked extensively in Kashmir over multiple bodies of work. She is not located there but has had a sustained intellectual and political engagement with its politics. Her perspective is not that of a Kashmiri but of a non-Indigenous Australian, acknowledging the role of the frontier wars in the colonisation of the Aboriginal land and people in Australia. However, her practice is rooted in wrenching historical incidents out of the past and recognising colonisation as an ongoing contemporary force. She does so by commenting on the complicity and violence of her own culture’s continued presence on stolen land. It is this philosophy that she expands from Australia to Kashmir.

For example, someone like Alana Hunt, an artist based in Australia, has worked extensively in Kashmir over multiple bodies of work. She is not located there but has had a sustained intellectual and political engagement with its politics. Her perspective is not that of a Kashmiri but of a non-Indigenous Australian, acknowledging the role of the frontier wars in the colonisation of the Aboriginal land and people in Australia. However, her practice is rooted in wrenching historical incidents out of the past and recognising colonisation as an ongoing contemporary force. She does so by commenting on the complicity and violence of her own culture’s continued presence on stolen land. It is this philosophy that she expands from Australia to Kashmir. I find these linkages useful in embodying the emancipatory slogan that none of us are free until we all are free and lifting the burden of liberatory politics from the Kashmiri citizen alone.

Her work, Cups of nun chai, began taking shape in mid-2010 amidst political turmoil that saw more than 118 civilians killed by Indian forces during three months of pro-freedom protests in Kashmir. In September of that year, when she returned to Sydney, she felt quite powerless and distant, perhaps a feeling we can all identify with when confronted with the agitated reality of places other than our own that we are attached to or resonate with in some way. Distilling her helplessness into a response and to move against the silencing and invisibility of Kashmir in Australia at the time, she initiated 118 conversations with people around her about its social, political and cultural reality. Many of them, with vastly different lived experiences, had never engaged with Kashmir. During every conversation, she brewed and shared a cup of nun chai. She then recalled each of those conversations from memory and wrote them down. So, while the book is a record of these conversations, I also see it as a process of keeping the dialogue about Kashmir alive. This could only be done from the outside, and it is critical work illustrating the value of art.

Now, from one metric of identity, she’s an outsider, but for me, she’s more of an insider to the reality of Kashmir and many Kashmiris I know than an Indian who has grown up with a binary view of Kashmir rooted in the spectacle of beauty or violence.

In the same vein, is caste only the burden of the oppressed to keep relaying that to the world? No, but perhaps those from dominant positions may need to engage with it from their own positionality. And complicity within the social order. So, constantly problematising the notion or definition of the insider-outsider is quite important.

Coming back to Kashmir, Witness, a photobook that features nine contemporary Kashmiri photographers, many of them photojournalists, is a great book and is not just a visual history of Kashmiri between 1986-2016 but also a record of photographic practices during that period. However, it foregrounds only male authorships, and apart from Sumit Dayal’s and Showkat Nanda’s work, it mainly deals with public spaces. In contrast, a photographer like Zainab, in her work The Weight of Snow On Her Chest, looks at the suffocation of everyday reality through the landscape of her home.

I feel that all these works, including Hunt’s, offer us plural insights about Kashmir, both seen in isolation and also resonant with other oppressions across the world.

Installation view of Weight of Snow on her Chest by Zainab exhibited as part of ‘Theatre of Dreams’ at BredaPhoto 2022 | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra

From the series Weight of Snow on her Chest by Zainab, 2020-ongoing | Courtesy of the artist

Taking forward the notion of the responsibility to respond, students at art universities in Finland often complain that they don’t receive adequate feedback. I, too, had a similar experience while studying here. Given the lack of time required for engaged feedback, feedback has become disappointingly sanitised. What has your experience been as someone who teaches and works a lot with photographers, many of whom are quite young?

While teaching—both in a classroom setting and as well as in a mentorship role (although I have a difficult relationship with this ‘mentor’ word)—I work with students and artists to develop ideas in their practice. So, I have become trained to respond to work constantly.

It is positive that institutions, at least it appears in Finland, are adopting practices like ‘safer spaces’ in response to a more equitable interaction. In educational institutions in India while I was growing up, often a hierarchical position was set between the student and the teacher, and the feedback space was at times weaponized to impose supremacy. It is important to imagine new dynamics in knowledge exchange. We’re all capable of falling into the same traps because we have emerged from the same system.

How do we make space to understand why students can’t deliver rather than reprimand them for their lack of accountability? Can their lived experiences have an impact on their performance? I have often thought of this with respect to Kashmir, where the notion of time is constantly fractured. How does a student embody the same work “etiquette” when their school or work lives are constantly disrupted? Perhaps regularly reviewing the student’s performance with regard to their lived reality and then finding solutions together may be helpful to keep them accountable.

I do feel, however, that any learning space should be a safe space where we can have difficult conversations. A teacher in India shared with me that during COVID, when universities were closed, the isolation that students faced was accompanied by a lot of mental health issues as well as a rise in access to mental health resources on, say, social media. He said after students came back from COVID, giving critical feedback became challenging; like, a student would say, you are triggering me and shut the conversation. We’re all capable of triggering trauma in another person, and many students are working with deeply personal, traumatic life experiences. So, how do we make that safe space where we are conscious of individuals who navigate those issues and still retain criticality? If we lose that space, we’re in a dangerous zone where we feel that some of us can’t be critiqued. Why not? Someone should always be able to oppose what I’m saying.

How do we make space to understand why students can’t deliver rather than reprimand them for their lack of accountability? Can their lived experiences have an impact on their performance? I have often thought of this with respect to Kashmir, where the notion of time is constantly fractured. How does a student embody the same work “etiquette” when their school or work lives are constantly disrupted? Perhaps regularly reviewing the student’s performance with regard to their lived reality and then finding solutions together may be helpful to keep them accountable.

So, how can students, artists, and curators develop methods of connecting their ideas with what is happening in the world?

It starts with being interested in human relationships. For example, my experience in Helsinki has been totally unexpected, and it is defined by the people I’ve met. I’ve been invited into community here. For me, that is often the breeding ground for most ideas.

When we were at Arles last year, all the artists came for the opening. We had previously worked together remotely for eight months, which was an intimate and challenging experience. When we came together at the festival, the group of 11 artists felt like a force, both a gentle community and a strength in numbers. The collective experience of being together helped to disrupt the tenor of the space, where most of us were proverbial ‘outsiders’ in what is a primarily Eurocentric space and had we been alone, our experience most likely would have been different. That feeling was both subliminal and powerful. It was about finding courage among each other. Such disruptions are great. I remember, at the award night itself, our group was the loudest in the arena. I heard cheering in Bengali and Spanish, even a celebratory howl—similar to ones I have heard back home in Orissa, enacted by women on occasions like marriage. We were a raucous bunch. We were getting shushed at times, but many in the group felt genuinely happy for one another that it didn’t matter. This is the reward I carried back with me. I want us all to cause those disruptions, not just in the exhibitions and the conversations we have intellectually but also as human beings.

Top row (from L-R): Vidisha-Fadescha/Party Office, Md Fazla Rabbi Fatiq, Isadora Romero, Nieves Mingueza, Tanvi Mishra, Vishal Kumaraswamy, Hien Hoang, Annaelle Veyrard/Rencontres D’ Arles | Bottom row (from L-R): Samantha Box, Lina Geoushy, Ibrahim Ahmed, Riti Sengupta, Soumya Sankar Bose and Kaamna Patel/Editions JOJO | Exhibiting artists and partner organisations of the Louis Roederer Discovery Awards, Arles, France, 2023 | Courtesy Tanvi Mishra