Portrait of Ani Phoebe, Photo: Daniel Stoelzner

Masha Glazunova is a music and culture enthusiast.

Ani Phoebe was invited to Helsinki to give a presentation for Sonic Club at the Museum of Impossible Forms and be in conversation with Miia Laine in an evening exploring how music communities can do solidarity work, thinking about justice when building music spaces, organising in times of austerity, as well as the importance of progressive promoters.

We met with Ani online across eight time zones to discuss her experience and views of DIY electronic music culture in Hong Kong. Originally from New York, having lived in Rio, and now nesting in Hong Kong, Ani is a DJ and human rights activist who founded and now runs the Bad Times Disco organisation. We talked about community organising, the story of Bad Times Disco, the harsh neo-liberal reality of Hong Kong, and the idea of a political dancefloor.

MASHA: I would like us to talk about electronic music communities and DIY approaches to doing things in that field. It would be interesting to hear about Hong Kong and the things that are happening there. I understood that Bad Times Disco started with you and your friend selling records together. How has it expanded to be as it is nowadays, and do you have many people involved in that work?

ANI: In Bad Times Disco, we have a team for the mutual aid work and then a team for the party work. In terms of selling records, it’s a bit difficult to find record sellers; you need to know what you’re talking about. I’ve been working consistently with some people, doing some overall training, and engaging. It’s a lot of training work and organised gatherings. I’m trying to find people with the same values and motives for involvement. I didn’t know before I started doing this party, and in general, before I entered music, that working in music, building a platform, and DJing is a lot of social responsibility. Before that, I was doing political community-organizing work. And, of course, we have to gather and organise people, and I was part of different solidarity economy spaces in Rio. And then, with music, it ended up being the same thing.

Photo: Ani Phoebe

It’s different for the mutual aid work since it’s very political. For the parties - it’s also political, but in a different way. Hosting a party is such a special thing. There aren’t good options in Hong Kong for the type of music and the type of people that we want to gather. So people are interested in becoming part of it if they want to take on a more active role.

Is it a volunteer-run organisation? I’m just curious since DIY cultural work often involves work being done for free.

The mutual aid work is voluntary. Everybody, including me, works on a volunteer basis [for the mutual aid work]. But it’s unfair not to pay people for production work for the events, e.g., selling records and parties. Everybody who’s part of our party or selling records is paid. And we try to pay a fair wage higher than the minimum wage. It’s about twice the minimum wage in Hong Kong because the minimum wage in Hong Kong is really low, especially for such an expensive city.

I always talk about compensation with people. There’s a lack of financial transparency in the music world in general. And there are a lot of events where people expect the staff to work on a volunteer basis in exchange for a free ticket. If I could avoid doing it, I would, for sure.

Photo: Iris Wang

Photo: Iris Wang

Do you feel that in Hong Kong, there is a well-composed network of DIY spaces and electronic music communities engaging with each other? How do you see it from your personal perspective?

Hong Kong is very fragmented and niche. Every underground community is a little clique-ish, and people stay in their social circle. In April of this year, we started a WhatsApp group where we, underground music [promoters], shared our dates and tried to collaborate with each other. The culture of collaboration is growing. I see people in the group trying to talk to each other and help each other.

Hong Kong is a very capitalist, neoliberal city. It’s very competitive and cutthroat in business in many ways. What defines whether people help each other or not is whether they approach their party as something that contributes to the music culture, community, and alternative scene, or if they approach their party as a business. I know many people who approach their parties strictly as a business here, and that’s because there’s money to be made. I do my best to be collaborative, but I’m also getting screwed over by people here. I want to stay open-minded and I want to be collaborative, and I want to be transparent, but you have to develop a sense of trust with people here, which is quite difficult. I think that’s very relationship-based.

In bigger cities that are hypercapitalist with higher class disparities, many relationships can end up being transactional and shaped by business. But it’s nice to hear about the underground promoter group. I hope it goes well and the network broadens. I have been wondering, where does the name Bad Times Disco come from?

It came from how I felt during the pandemic. I felt we were living in a crisis within a crisis. I’m not very optimistic about the current systems that we’re living in and how much progress we are making in terms of getting out of this system. Still, the way that I deal with my disappointment and my despair is that I turn to music, underground art, and artist-activist communities. That was very helpful for me during a time of political disappointment in Brazil and the far-right winning in Brazil and everywhere. And then I came to Hong Kong, reporting on the protests. And then, mainland China cracked down on the protest, and they passed the National Security Law during the pandemic. I find solace and community through music and gathering with others who share my values. We have the social responsibility to do something. Bad Times Disco refers to finding moments of joy during crises and within harmful systems.

We have to organise with the community that we have. I have turned away from organising with this dystopian, dark, pessimistic tone. I want to organise using more positive emotions and more hope. I’ve noticed that many people who are very hopeful and optimistic about the world are white Europeans. I know this because I’m in a narrative strategy group of hope-based communication people. So, I just wanted to communicate that I’m not a completely optimistic person, but I’m not a complete pessimist either. Bad Times Disco encapsulates that, and I think people get it.

I guess parties have historically been places for people to gather together and enjoy life. In the past 50 years, the history of electronic dance music, parties, and organising parties has had a very strong political aspect to them: What is being on a dancefloor like? For whom and how is one organising a party? It sounds like these ideas are part of the Bad Times Disco ethos.

There is something that is a bit damaging about how identity politics has taken over the leftist discourse and is kind of used as a signifier of progressiveness. I’m very influenced by intersectional feminist politics, and I think in a multi-dimensional way. In the dance music world, I see progressive parties only thinking about one aspect of identity, and they’re not really talking about class, political systems, or organising against the far-right. We are not exactly catering to any specific identity group in Hong Kong because it’s a very fragmented landscape here, where the expat scene is very divided from the local scene. And then the local Chinese scene is also racist towards the minority groups in Hong Kong. By not talking specifically about just one aspect of identity, we emphasise that our main politics is radical inclusiveness and that people who are privileged take up disproportionate space, and they need to be aware of the space they’re taking up. This is a party that is diverse and inclusive. For example, Hong Kong is a place that is unfriendly to people with disabilities. We are not even able to host events for people with disabilities. There are literally building limitations, and it’s something that we’ve always communicated since the beginning of BTD. Just thinking about different aspects of inclusiveness, it does affect the crowd and the type of people coming. We’re constantly trying to think of ways to make the party more inclusive, and we probably need funding. Maybe we should work with specific community partners so that we can develop a party concept with them. Inclusivity is an aspect of BTD that is constantly in progress. It looks and sounds different than the current signifier of progressiveness in electronic dance music, which needs to go a lot deeper.

Photo: Iris Wang

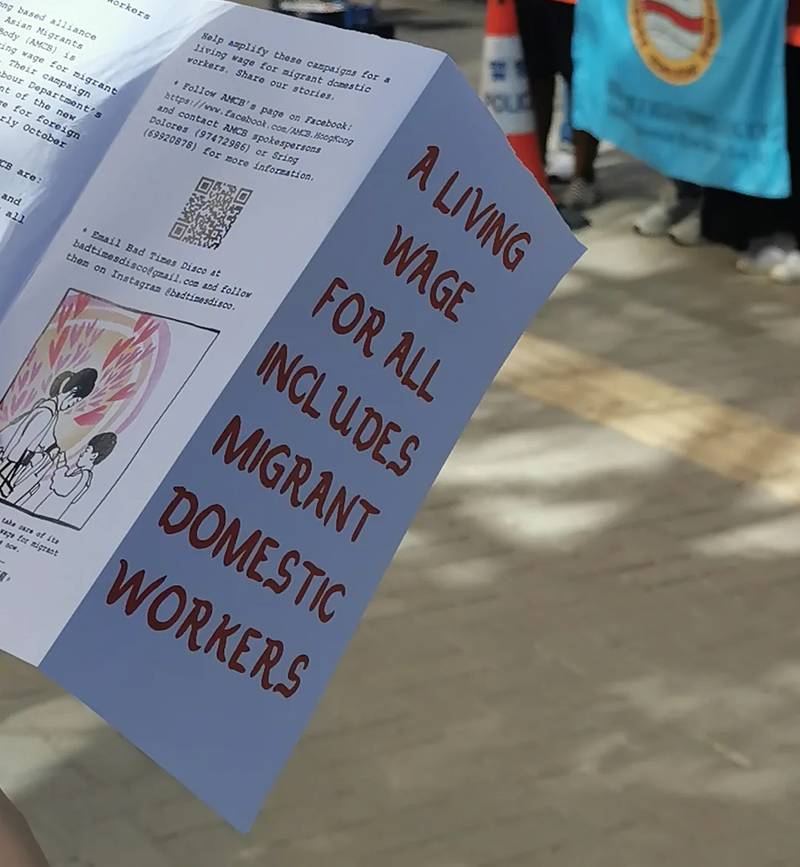

Image provided by: Ani Phoebe

I believe in community spaces for specific communities that have been historically marginalised, but there are a lot of other issues going on. We made this joke with my friends where we said, “Oh yeah, this is primarily a gay or queer party, but these are like the richest gay and queer people that we know; they’re so class privileged, that’s why they’re able to do this party’’, and nobody talks about it. We need to talk about how to make parties, leisure, entertainment, and political participation more accessible for people who are struggling to pay the rent.

You have an ongoing campaign with BTD. Would you like to say something about that?

We have an ongoing campaign that we co-launched with the Asian Migrants Coordinating Body at the beginning of September. We developed a solidarity campaign with migrant domestic worker activist organisations based in Hong Kong. AMCB and all these other migrant domestic worker groups are very old at this point, like 30, 20, and 10 years old. Migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong are the most organised globally, after the US [where they are very organised and have made important labour wins]. Hong Kong has the highest wages for migrant domestic workers in Asia because these groups have organised, campaigned, and protested for decades. However, just because they have the highest wages in Asia doesn’t mean they are fair. These workers are still being exploited because they don’t have any type of labour protection in general, and the wages that they receive are lower than the statutory minimum wage for Hong Kong residents and citizens. So, AMCB and other organisations came up with their living wage rights and a food allowance.

Promotional booklet for the ongoing campaign

What we did with BTD was that we joined them and developed this campaign together to amplify their demands. Our approach to this campaign is to focus on storytelling and comics. There’s a trend nowadays called illustrated reporting, or comic journalism. It’s growing, and it has to do with social media and how saturated with news and information we are. Humans respond better to stories; if we can emotionally connect with a story, we internalise those facts better than if they were just written out as facts in an article. Every Tuesday, we share a comic story that is based on real-life stories. We have interviewed migrant workers, and upcoming content will be interviews with employers in Hong Kong. This campaign is ongoing until the end of October. I’m excited about it, but honestly, I’m a little bit overworked right now and overwhelmed. I believe it is going to be good when the whole thing is done.

What does resistance on the dancefloor mean for you?

For me, it doesn’t mean that everybody who comes to a party is progressive or that everyone who’s dancing is resisting the world in some way. I mean, there’s a lot of dance music culture and electronic music culture that just perpetuates capitalism and the status quo. I understand it more as applying to the people who are organising and trying to contribute to changing society and the system that we live in in some way. This type of opposition to the world is exhausting. These people need to hold on to their joy, to dance, and to be in communion with each other. For other people who are not yet active in any type of social, economic, or political issue, finding a dance floor like Bad Times Disco, a party that is more politically conscious and community-oriented is like an invitation to get civically involved in some way.

Resistance on the dancefloor and vague concepts like this have been commodified and marketed at this point, so people are trying to sell you things to make you feel good about yourself. If you approach anything as a consumer experience, you’re not really going to be in opposition to anything in the world. You’re not going to resist anything; you’re just perpetuating it. I hope that people will see the dance floor as a radicalising kind of moment. I had the same kind of moment for myself. I was mainly going to parties and dancing, which is another form of participation, but I was not active in organising or convening stuff myself. There is a shift for people when they decide, ‘OK, I can also do something, right?’. It’s based on experiences that you have and things you would like to change. The approach to ‘’I want to organise parties and do something different’’ can be applied to your neighbourhood or your city.

Finally, what makes a good dancefloor for you?

A good dance floor is one where people are dancing. First and foremost, if you’re dancing, it means that you’ve kind of let go. And you’re willing to engage in a communal experience because you have to let go of your self-awareness, your individual fear or insecurity, and then you enter this kind of experience that is larger than yourself. That’s why I think it’s a potentially radicalising experience. I read this great book this summer called ‘’Everybody: A Book About Freedom’’ by Olivia Laing. It’s a book about the physicality of the body, how much is stored in it, and how the body is one of the most radicalising experiences that we can have. Our bodies are subject to so many things, and specifically for some bodies more than others. She wrote this chapter on how, the first time she was ever in a protest, she felt the same kind of sensation in her body as the first time she was ever in a rave. It’s very much about the physical vulnerability of your body in that space and being transcended out of your individual limitations. So yeah, I think that’s a good dancefloor.

Photo: Iris Wang

Photo: Iris Wang

Yep, I have heard that quote as well about the rave and the protesters. I hope that one day there’s gonna be a Good Times Disco when people are more proactively changing the current systems and things are going better for our dying planet.

Maybe we’ll have a celebratory party one day, but I’m not exactly sure.