FLIP! Skate & Art, Installation view, Photo: Anna Autio, 2023

Max Ryynänen is a Helsinki-based ex gallerist (ROR Gallery, Kallio Kunsthalle, Gallery KLEIN) and writer (essayist, novelist). He has written on film, dance, theater, and visual arts for Flash Art International, Ice Hole, Art Pulse, Kunstkritikk, Atlantica Internacional, Filmihullu, Taide, Teatteri and Esitys. As a scholar Ryynänen has studied film, kitsch, rap music, heritage, art systems, sports, aesthetics vs. politics, architecture, and aesthetic/somatic experience. For more information, go to http://maxryynanen.net.

The Vantaa Art Museum Artsi has long established itself as a museum for post pop art and the visual culture of the youth – quite often only Americana. However, it has recently provided a platform for more conceptual and political takes on art. Situated in Myyrmäki, at one of the most rogue malls in the metropolitan area (well, it’s Finland, but still), it has both commissioned graffiti (with Street Art Vantaa) and actively documented graffiti in its environment. One of its strengths is its open-minded attitude towards contemporary visual phenomena. It has played an active role as a premiere venue for many young artists. FLIP! Skate & Art, the summer exhibition for 2023, is on skateboarding.

Skateboarding is not totally new to Finnish art museums. In the early 2000s, The Side Effects of Urethane, a skater collective, took over Kiasma’s 5th floor. The skateboarders outside of the museum had, though, already become an integral part of its brand right after its topping out ceremony (1998). Skateboarding and contemporary art also had a (b)romance in the late 1990s and early 2000s in California, where the so-called lowbrow movement first exhibited in skateboarding and surfing shops with an accent on humor, psychedelia, and rogue streety visuals. It grew from the remains of the San Francisco underground, but it was also fueled by frustration with never ending, high-priced modernism and maybe even more by academic postmodernism in the Los Angeles art scene. It provided a new scene for comic and visual artists like Robert Williams, Mark Ryden, Amy Sol, Margaret Killgalen, and the slightly off-road (representing Fisherman Village in Seattle) Charles Krafft, who shared a graphic approach to art spiced up with 10% conceptualism. The art journal Juxtapoz, which became the ‘official’ publication of the movement, also presented murals, post hippie mysticism, and car painting (Von Dutch) – without forgetting the art of painting skateboards and surfboards.

Krafft (1947-2020), who in the late 2010s (possibly following his brain tumor) suffered grave mental problems and became a Holocaust denier, rose to stardom in the early 2000s for doing literally anything that you should not do with (17th-century) Delft ceramics, a method he had learned from a Dutch Hell’s Angel. He produced plates, cups, bullets, and tea pots painted with uncanny personalities and catastrophe scenes (Charles Manson, the SS Andrea Doria, the Hindenburg) and hung out with the Neue Slovenische Kunst movement (including the band Laibach). The legend has it that the Slovenian war museum still displays Krafft’s porcelain AK-47s, which Wired called “pacifist kitsch” in the good old days. Krafft broke the code for the use of a method and a material (porcelain, China painting), which, in the West, had mainly been restricted to picturesque and cute animals. One can say that in terms of content, the height of continental European porcelain was like a slow, bourgeois version of Instagram in its time (cute cats, ‘nice’ sceneries) – but Krafft turned it streetwise and underground. At the apex of his career, in a scene which exhibited in shops for skaters and surfers, he, of course, also produced porcelain decks, which gained wide image distribution in the 2000s.

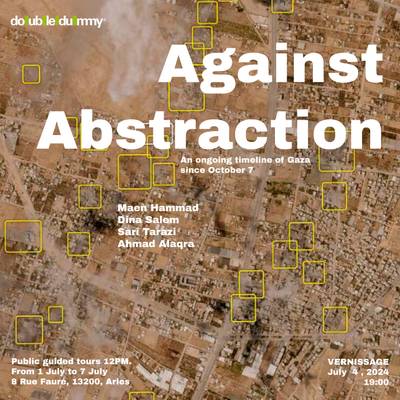

Man Yau, Freehand Series and Porcelain Decks, 2012. Image: Anna Autio

I have no idea if Man Yau (1991-) knew of this iconic connection, but I felt a pleasant catharsis watching her delicate ceramics being exhibited and skated – and eventually broken, partly as a new take on porcelain skateboards in art (a more functional one, being skated until the sweet-bitter end), but partly also through just the breaking itself. Breaking things feels cathartic for many today, and in this world where we are surrounded by too many things and products and where sometimes (I am referring here to the existential debate initiated by Mario Perniola), we start to feel that we are just fragile ‘things’ ourselves, just looking at it is nice. It also felt like porcelain skateboards would have been recovered (while they never really existed, although Krafft was often copied at the peak of his career) from the grim darkness where the lowbrow movement had accidentally taken it. Yau’s 2012 video Porcelaine Decks (3:21 min., involving Taito Kawata for DOP and post production and Mikko Kivikoski as skater) is beautiful, fragile, and somatic, from graceful movement to the final breaking of the object, which can be emphatically felt by the viewer. The video has great framings and cuts and surprises with sudden close-ups of the skater, which worked well to holistically embrace the act itself and the human being behind it, not just the destiny of the object.

Yau’s exhibited decks (Freehand Series) are impressive studies of porcelain as a vehicle for framing and understanding the world (in this case, skateboards, skateboarding, and street culture). I felt like touching them, but I obeyed the museum rules, as ‘an official looking person’ (Finland is full of them) in the exhibition space looked like a ‘snitch’. Yau first presented her work at CaliHelsinki, a skateboard concept store, but it looks great in a museum environment too and has surely not lost any of its charm in Artsi. Perhaps Artsi’s loose atmosphere is really useful for this kind of juxtaposed work.

Otto Karvonen (1975-) has established himself as a political artivist both locally and internationally; however, his work does not build on clashes or affects like most political art. In Security Flip Shifty (2005, 8:33, post-production, Timo Valo), a group of skaters dressed as security guards roam the central cityscapes of Helsinki, like the Kompassitasanne under the Railway Station. As the classical cat and mouse game of workers and loiterers, i.e., security guards and skateboarders, has continued for as long as I can remember, Karvonen’s video, where a group of skaters take on townscapes from central Helsinki in guard suits, felt like a United Nations type diplomatic move. I felt a kind of a healing experience watching it. Skateboarders have always loved and hated security guards, who roam the same spaces, destroying many beautiful skating moments, but who also represent a desired boundary and authority to oppose, which is important for young people who search for themselves by rebelling against authority. Guards, underpaid and under-appreciated, are truly at the core of today’s exploitation of workers, so it has always felt awkward watching middle-class skaters teenily ‘revolting’ against poor workers. Karvonen – this is the strength of his art – distributes dignity to everyone. In his earlier work, like Racists Half-price (2017), people who said that they were racists could get a discount on strawberries at Riihimäki marketplace. This time, through a non-discursive act, he gently hits the dialogue button. Any UN mission could have Otto Karvonen doing artwork as he glues together and opens more dialogue than he breaks. Security Flip Shifty, which I had not seen before, had some nice moving image takes and a pleasant rhythm. Also, the soundtrack showed appreciation for the audio side of skating, a very important facet of the culture. Urban noise has always been central to skateboarding – from provocation to sheer sensual pleasure.

Otto Karvonen, still image from video: Security Flip Shifty. Image: Petri Summanen_KKA

The culture that the skaters built and distributed all over the world developed, like any culture, partly through interest and creativity and partly by accident. The great American drought of 1976-1977 emptied swimming pools, made them a popular place for the practice (bowl skating), and produced moves and a tradition of form that still haunts skating ramps. Certain clothes, marijuana, tattoos, and, of course, music were adopted. Rap, post punk and garage rock landed naturally on the cultural formation. They worked well with the audioscape of the streets and the noise made by the skates. They long remained as the soundtrack of the practice, moving from ghettoblasters to being background music in skating videos.

The practice has come a long way from its underground, semi-criminal ‘golden age’, to today’s well-marketed and safer (protection for injuries) hobby, where skateparks now reproduce the forms of the swimming pools and the early Californian streets where things first happened. But skateboarders are still tricksters of everyday life (Karvonen’s video embraces this) with a whole subculture built around the practice.

Like I said, skateboarding quickly picked up the kind of video use that later became iconic in popular culture through groups like Jackass and The Dudesons and then an everyday practice with cell phones. Skateboard videos featured tricks, sometimes successful but often not ending that well, leading to shouting and crying – and emphatic reactions from the viewers. VHS was the classic format for this somatic culture, and even more, VHS cassettes that had been copied too many times, leaving traces in the image. Skateboarders really pioneered the use of video, so much so that nowadays it is hard to understand it. No one in the 1990s filmed their practice all the time, except for them and a handful of contemporary artists.

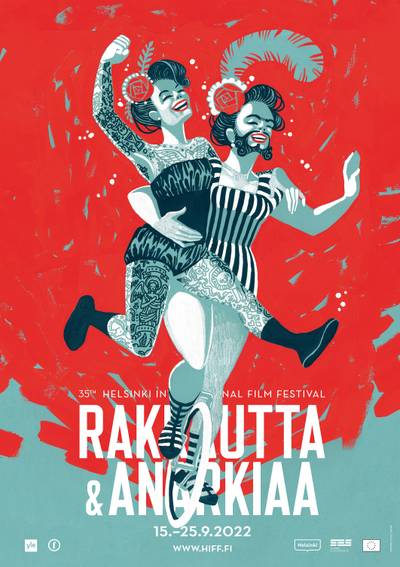

Emilia Mäkelä’s Just to heal you (2023) plays with this early visual culture of skateboarding videos, their bad quality, glitches, and cheap fonts (at the time, you couldn’t use anything else, as they were often served by the VHS system). Mäkelä’s work is a beautiful hommage to the media and its bad quality, the whole experience of DIY videomaking in the 1980s and 1990s. Eeva-Mari Haikala’s work, Hello Pedro (2023), a video executed for the exhibition, is on the same track, visibly a tribute to the experimental nature that connected early video art and skateboarding footage. Both were about testing limits – visual and somatic.

Anssi Kasitonni, Sekvenssi, 2005. Image: Anna Autio

Emilia Mäkelä, Just to Heal You, 2023. Image: Anna Autio

Anssi Kasitonni (1978-), who has shown lots of love for ‘bad quality’ (also through video), is kind of a must for all Finnish, pop-driven exhibitions, where his do-it-yourself style has possibly made some visitors a bit skeptical (not me though). Sequence (2005) is not the most typical Kasitonni work, as it is devoid of trashiness. Toy soldiers are spread out in casting resin on skateboards, giving the impression of jumping over a pit. The work remains more enigmatic than other Kasitonni works, and again, it was something that I had not seen until now, which nails one of the credits of this exhibition, in presenting good archive work. Also, as all these works are seen together, their perspectives and usage of skateboarding as a topic and way of looking at the world begin to accumulate into a broader, collective vision.

Skateboarding landed in Finland in the 1980s and rose for a moment to be nearly a big thing, having Finnish championships on TV, and it stayed. Like breakdance, it was often rural, referring to its very urban origins, and one can still find skateparks next to cows and misty forests here. This non-urban side of Finnish skateboarding came to mind while watching Fia Linnéa Emelie Doepel’s visual-ecological work Hiisi (2023), an hommage to ecosystems and a presentation of their fragility – with a visual touch with roots in skate-like visuals. Timo Vaittinen’s large textile work (Untitled, 2023) had a sort of green forestry feeling about it. It was one of the works which had less clear traces of skateboarding and its visual culture, but worked as a reminder of the artists which skateboarding has pushed into the art and design scene, through its strong DIY visual culture, which in skateboarding videos comes up often after the skating – the skaters selling their works.

Timo Vaittinen, Nimetön, 2023, Image: Anna Autio

Fia Linnéa Emelie Doepel, Hiisi, 2023, Image: Anna Autio

Peetu Liesinen (1988-) I suppose, is a sort of a must for the exhibition too, with his VICE-like, DIY-driven and trashy painting activities. Untitled (Covering trauma with attitude) (2023) does not show much but kind of has the spirit. Exhibited among clearly skateboard-driven works, its brown background (with hidden life) and an inserted black-and-white face are somewhat reminiscent of skating ramp materials, intentional or not. The paintings of pro skater Fabu Pires (1978-) are then more like cut-and-paste from street art. The Four Elements (2020) and Fire (2020) could just as well pass for everyday interior art, but knowing the connection interestingly gives them a mural-like feeling. Sometimes visual meanings are about the context. Ville-Veikko Viikilä’s poppish paintings are fun color bombs with an aesthetic street art margin, and bring to mind the already mentioned lowbrow-movement with their cartoon characters, snakes, and palm trees, being, though, more clearly art scene art. The same can be said for Erno Pennanen’s dramatic ladies (Steak and a Jacket (2022) and A Jacket (2022)), fun paintings that have a street side margin to them but could just as well be from a 1970s modernist or naivist exhibition.

The exhibition also features works by Alvi Hatakka, Saara Karppinen, Hermanni Keko, Santeri Salminen, and Valtteri Kivelä, not to mention (looping) films by Mikko Björk, Juice Huhtala, Samu Karvonen, and Sami Sänpäkkilä. Watching skating films in the rear part of the gallery space was pleasant, and I enjoyed the documentary extension of the exhibition.

FLIP! Skating and Art feels like a flea market, not like one of today’s strongly curated exhibitions. No textual or visual framework guides the audience. I have no problem with this. The overall feeling is, though, a bit lame. I am trying to ask myself why, as there are some great pieces in the exhibition. There could have been more edge or depth, and paths to break. I don’t mean that the exhibition should have systematically built a spearhead for its take on skateboarding – it is, actually, good as it is – but I felt like I could have been a bit more surprised, shaken, questioned, and/or affected. I might sound like a bad critic (and I might be one) as I cannot point out what this could have been, but, for sure, I appreciated the archive work of the exhibition builders, the artworks, the loose atmosphere, and of course the fresh choice of topic. Nothing was taken very far. Of course, one could think of FLIP!, with high respect to popular culture, as more strictly a popular culture exhibition, meant for hanging out and digging – not to support the dichotomy of art vs. popular culture but to accentuate meaningful differences in interpretation, experience, and atmosphere. If so, why not make this more into popular culture? Go for the ‘cool’, or build an ‘awesome’ experience? Could this be Artsi’s path in the future? The metropolitan area does not have a museum of visual culture.

I feared the catalogue for various reasons. My nightmare would have been a book with a personal article by a “street cred” pop “intellectual” like the rapper Paleface “keeping it real”, another by a local one-man franchise of Anglo-American cultural studies appreciating the practice with trendy concepts and revolutionary rhetoric. Gender talk could have worked, and I am happy to see more gender balance and diversity in the skateboarding scene in recent years. In any case, I think only a really, really bold and fresh take on writing – or an incredible writer – could have saved the book. So, I was relieved when I heard that a catalogue hadn’t been published. After walking out, though, I felt disappointed. It would have been nice to look at the images. The culture is so visual. Now images talked, though, in the exhibition.

FLIP! Skating and Art does not do much to tackle the art-like qualities of skateboarding (if not in Yau’s film). Many moves are done to leave an aesthetic impression, and one could view skateboarding as an aesthetic culture or (broadly speaking) an art. Yet there is no artistic and/or aesthetic analysis of skateboarding itself anywhere, neither exhibited nor written – which is a pity. As my own background included the whole network of practices which surround skateboarding, but not the board itself – I broke my bones with rollerblades – I can see the potential, but I’m a bit removed from the practice to be able to write it. Looking forward to see if someone grabs the initiative!