ONE DROP, 2023, Image: Tuukka Ervasti

Leonardo Custódio currently works as a postdoctoral researcher at Åbo Akademi. He has founded and coordinates, with Camilla Marucco, the Activist Research Network in Finland. Working at the intersections between academia, activism and organised civil society, Custódio is a leading scholar on collaborative knowledge production about media activism and communication for social change.

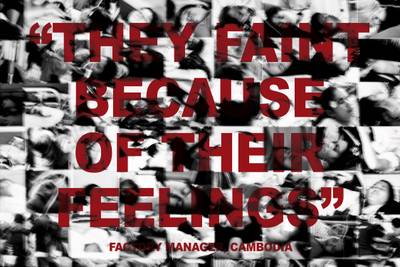

For a few years, I have taught and spoken about “anti-racism communication as practises of love” – that they are a multitude of symbolic, material, and physical actions and expressions that serve as medicine against the hate constitutive of racist ideas and behaviour. By medicine, I mean the long-term individual and collective efforts among people historically suffering from racism. These efforts encourage mutual healing and prevent wounds from the consequences of racist violence constantly cutting through the lives of people deemed inferior, dangerous, and disposable before, during, and after colonialism.

One great example of anti-racism communication as practises of love is Sonya Lindfors’ latest work, ‘One Drop’ (2023). In this essay, I, a Black, heterosexual, cis-gendered male scholar from colonised Brazil, describe the experience of attending one of the live performances at Tanssin Talo in Helsinki. A couple of months have passed between watching the work and writing about it. Despite that, I can still feel the performance’s empowering effect lingering in my scarred yet decolonizing, self. Therefore, this is not a review of the choreographic work—something I would be unable to do—but a critical analysis of the multiple meanings emanating from the performance, varying according to each audience member’s relationship with histories of racism and legacies of colonialism.

I was very excited as I took the train from Vuosaari to Ruoholahti to see the second-to-last performance of ‘One Drop’ in May 2023. I have greatly admired Sonya Lindfors’ passionate multitasking, political creativity, and choreographic talent since I saw a performance of ‘Noble Savage’ in 2016. This admiration only grew when I met her in person in the winter of 2017 to discuss possible collaborations at #StopHatredNow – an annual platform for anti-racist dialogue – by UrbanApa – an art community of which Sonya is an artistic and managing director. I remember sitting in awe across from her as she spoke of feasible revolutionary actions and a fierce commitment to dismantle whiteness in Finnish cultural institutions, one collaborative work at a time.

‘One Drop’ is a collaboration between Sonya Lindfors – a Cameroonian-Finnish choreographer and artistic director – and a working group including talented artists from the global African diaspora. They are Ghanian-Finnish actor and performer Antonia Atarah; Uganda-born movement artist, street dancer, and photographer Hamis Ahmed; Finnish-Nigerian multi-disciplinary artist and experimentalist Nori Kin; Oslo-based contemporary dancer, choreographer, and pedagogue Alma Bø Getachew; Oslo-based dance artist and performer Mariama Slåttøy; Sudanese-Ugandan-descent performer Geoffrey Erista; US-born mezzo-soprano, harp player, and freelance performer Isabella Shaw; and transfeminine designer and performance artist Angel Emmanuel. The exact way this collaboration happened in the working group is not accessible from an audience perspective. Still, the ways in which these artists’ experiences and creativity informed the performance were evident. ‘One Drop’ represented Blackness in the multiplicity of skin tones, accents, genders, ancestralities, and futuristic imaginations intrinsic to the nuances and diversity that constitute indigenous and diasporic Africanness. Together, the team created a joyful, multifaceted, and politically powerful afrofuturistic performance.

ONE DROP, 2023, Image: Tuukka Ervasti

Decolonial Housekeeping Instructions

The ‘One Drop’ experience started at Lasipiha, the lounge area where people hang out as they wait for performances at Tanssin Talo. I noticed the lounge area was full of mostly under-30 white people. It felt bittersweet. I would have loved to see more Black and Brown people in the audience (which seems to have been the case in the evening sessions). However, seeing so many young white people made me smile. The conceptual and provocative description had not intimidated them.

The first paragraph of the playbill read: “ONE DROP is a speculative summoning, a decolonial dream, an autopsy of the Western stage and an operetta. Slipping in meanings, leaking through different categories the work dives into the poetics and politics of relations, creating a stage that awakens the ghosts, connections lost or forgotten.” This text may be challenging to grasp if one is unfamiliar with decolonial theory and discourse. Despite this possibility, the full house reinforced a perception I have had in my own anti-racist work – white Finnish artists and activists have increasingly overcome their own discomfort to listen and learn about racist histories so that they can act against racism in their everyday lives. The Finnish anti-racist future looks promising, even if the current political reality feels grim.

These hopeful musings ended abruptly when the backstage doors opened, and Sonya Lindfors came out. I would describe what happened after that as an important resignification of established practices in historically elitist and excluding Western cultural institutions. Joining the crowd at Lasipiha, Sonya grabbed a chair, stepped on it, and, cupping her hands into a megaphone, requested people to come closer. Then she used her charisma to turn a basic housekeeping announcement into a decolonial exercise. After welcoming the audience, she explained that what we were about to see was not an act of contemporary dance and that some of the artists never had formal training. For anyone healing from colonial scars, these otherwise trivial words could feel like a balm of empathy and belonging.

As she stood on that chair amongst the audience, Sonya masterfully created a strong sense of inclusion and participation. Coming from her, the usually cold and straightforward requests to mute or turn off phones gained the contours of a collective effort to prevent disruptions to everyone’s experience. She also led us into practising “Anna mennä!” and other cheering phrases. The point was to encourage and share support with the artists throughout the performance. As I watched her, I thought of how such a simple act, the willingness of the director to be present and connected for an announcement before a performance, can have a deep decolonial effect.

Love in ‘One Drop’

I wrote earlier that I believe ‘One Drop’ is a great example of anti-racism communication as a practise of love. Perhaps some expansion of this idea is in order. Broadly speaking, we can think of two types of actions against racism. On the one hand, there are those actions where people react, confront, and dismantle racist ideas, behaviours, institutions, and structures. On the other hand, there are actions meant to create conditions for mobilising collectivity, mutual support, healing, and empowerment. Both have love as a moving force in opposition to the ingrained hate constitutive of racism in all its manifestations. By love, I refer to the deepest form of care, empathy, respect, and solidarity we can feel and express in our words and actions towards our fellow human beings and the social and natural world we share. Actions against racism, even those expressed in anger, are fundamentally actions of love. They all aim to improve and protect people’s quality of life, human rights, and access to justice (in contrast to the exploitative, excluding, and destructive nature of racism).

In what ways would “One Drop”, a performance developed and executed by racialized others in Finland and elsewhere, express love in its enactment of mutually transforming anti-racism communication?

ONE DROP, 2023, Image: Tuukka Ervasti

Lasting approximately two hours, ‘One Drop’ has three parts. In the first part, Black bodies occupy and revitalise the Western “contemporary stage,” a space that traditionally excluded Black folks with its expensive ticketing and artistic under-representation. In the second part, the artists conduct a thorough “autopsy of the Western stage” after turning Pannu Halli into an operating theatre. The third part aligns with Sonya Lindfors’ other works exploring future utopias, such as ‘Cosmic Latte’ and ‘We Should All Be Dreaming’ (practised in partnership with Maryan Abdulkarim). ‘One Drop’ ends with humans from the future finding the ruins of civilization and imagining the meanings of their past. In hindsight, what I often find notable in dramaturgical works by politicised Black people is how they combine messages everyone can grasp with those that only people who have shared the experience of a lifetime dealing with racism can feel. Even more interesting is that even if Sonya Lindfors had planned this unspoken sensorial connection with us, the Black audience, the specific ways in which we felt this message would vary according to how we had experienced and problematized racism in the contexts with which we were most familiar.

Take the opening act as an example. As we walk into the room, we see a character (Hamis Ahmed) moving loudspeakers to the centre of the stage, a character (Mariama Slåttøy) placing what looks like a covered painting on the side, another character (Alma Bø Getachew) dragging a small stage, and Sonya Lindfors welcoming the audience and guiding them to their seats. Throughout the opening act, we listen to the song “Could you be loved” by Bob Marley and the Wailers, whose music has sown the Jamaican One Drop rhythm worldwide. The playbill explains the double meaning of One Drop: both the reggae beat and the one-drop rule in the segregated U.S.– any trace of Black ancestry makes one Black regardless of skin tone. In the actual space of the theatre, however, most people seemed to take the song as a welcoming background track while they found their seats, chatted, and took their selfies while Black artists set the stage apparently unnoticed.

Witnessing this dichotomy, it occurred to me how I had naturalised the fact that in most cultural institutions in post-slavery, Western, and Westernised societies like Brazil, Black folks have historically worked primarily in service, maintenance, and security—standing on the corners, watching from the shadows, or cleaning during the closed hours. Moments later, a character (Geoffrey Erista) carried a marble-finish bust of a Black woman onto the stage. As the character carefully walked across the stage, it was as if they both stared at us, condemning racist histories and complicities. The song served as a reminder: Black folks can love and be loved while healing from colonial scars in their bodies and souls.

Soon after, Mariama Slåttøy, in a black leather jacket reminiscent of the Black Panthers, and Hamis Ahmed danced to Steel Pulse’s iconic “Handsworth Revolution” on the stage covered in smoke, resembling both a Jamaican sound system and the aftermath of a riot. The juxtaposition of revolution and dance created a compelling representation of the embodiment of joy and mutual love as expressions and actions for justice and dignity that have shaped Black dissent in Africa and the diaspora. The song gets stuck on the term “revolution” as they dance. Suddenly, a futuristic-looking character (Nori Kin) runs and slides across the stage like a ray, disrupting and transforming the scene. Immediately, the song stops, and the artists take the stage together, performing different types of contemporary dance to the crude machine’s hissing noises. The political and emotional aspects of the dance had vanished. It was as if the character Kin represented had removed the revolutionary power of the dance and left it with abstract and incomprehensible aesthetics instead.

If the allegorical criticism of Western institutional appropriation of Black bodies and creativity was not evident enough, it becomes clear during Antonia Atarah’s samba solo, a fast-paced, artificial-sounding samba beat typical of caricatural performances of traditional dances in exoticizing touristic nightclubs across Latin America and the Caribbean. In those spaces, Black women would display, in hypersexualized moves, bright colours, and exaggerated facial expressions, a version of samba that appealed to gringos and enriched institutions but bore little resemblance to the ancestral history and matriarchal traditions of samba culture. Including some funny lines (verses of Beyoncé’s “Formation”, for example) in Kin’s representation of a monstrous institution squeezing the skills and strength out of Atarah’s character until she falls and vanishes was brilliant. In the session I attended, people in the audience laughed when Kin’s character seemed to squeeze Atarah’s samba dancer while moaning in orgasmic ecstasy and bestial satisfaction terms like “Black exploitation”, “degradation”, “violation”, and “colonisation”. Inadvertently, the laughter in the audience made the brutality of the act realistically whole.

In contrast, what follows is an elaborately wonderful representation of Black love and collective artistic and creative resistance. In a darkened room, a character (Mariama Slåttøy) appears in the spotlight wearing a shiny, golden dress. To a classical rendition of the French chanson “Mille Regretz” (A Thousand Regrets), Slåttøy literally shines in the dark while other characters slowly walk and crawl towards the bust of the Black woman in front of which they stand, as if in reverence. Soon, led by Slåttøy’s character, they enter, in formation, to march to rhythmic stomps and what sounds like “Songa Mbele!” (Swahili for “move forward!”) as a cadence call resembling an African tribal war chant. The act ends with Hami Ahmed and Nori Kin sharing the stage to dance together with gentle moves and tender touches until they carry each other off stage. It felt powerfully symbolic that a female performer led the march and that male performers expressed care and affection for each other. These acts highlight Black women, who are the ones who suffer the most from the historical legacies of colonisation, and the sensibility of Black men, historically hardened by colonial patriarchal exploitation and influence.

ONE DROP, 2023, Image: Tuukka Ervasti

The criticism of Western cultural institutions becomes even more explicit in the interlude. An energetic and beautifully sarcastic Antonia Atarah interacts with the audience as she walks down a narrow metallic spiral staircase to represent the challenges Black artists face in forcing themselves into Western (aka white) institutions. In an interactive monologue, Atarah delivers a critical commentary on what it has meant for them, as Black artists in precarity, to occupy the prestigious and often expensive contemporary space of Tanssin Talo. “But for real, these spaces are very exclusive and hard to get into. Concrete. Concrete. Concrete. Concrete. And regular tickets cost 42 euros! Whaaaaaaaaaat!? How much is this scene worth?” Following this critique, Atarah and Kin perform an auto-tuned duet of a remix of Bob Marley and the Wailer’s “Could you be loved?” infused with mutually affirming lyrics. Joined in the party by the other performers, they empower each other to resist the excluding cultural structures without giving up love for themselves and their craft.

The second part starts with performers dressed in hazmat suits. Elton John’s “Sacrifice” hilariously plays in the background. To the music, they cover the stage with a long white sheet to turn it into a sterilised operational theatre for the “autopsy of the Western stage”. Once the stage is set, Isabella Shaw enters the scene, covered in red paint for blood, and sings an aria. As she sang, I wondered if anyone else had ever seen a natural-haired Black opera singer before. I hadn’t. The act follows with other characters joining the stage and, wearing white clothes covered in blood, talking as vampires to represent individual and structural manifestations of colonial ideas and practises throughout history. As the scene unfolds to its catastrophic ending, I wonder if the white people in the room were also disturbed and emotionally affected as I was. Will they request or even demand more performances and acts by other artists who are not white? Will they demand more fair prices for inclusive access to cultural venues in Finland? Will they open themselves further to the voices and creative power of artists who are not white? It remains unclear what impact ‘One Drop’ will have on white people’s attitudes regarding racism and exclusion in the Finnish cultural sector. Regardless, the capacity of Sonya Lindfors and the team of absolutely talented international Black performers to turn decolonial critique into an abstract and humorous yet clear and profound piece of creative work demonstrates the urgency to dismantle the hold of whiteness over Western cultural institutions.

How do you make sure the humans of the future in ‘One Drop’ are right?

The assumptions of the future humans in the third part regarding the ruins of their past, our contemporary civilization, serve as a guide. As they examine the ruins, including the bust of the Black woman, they imagine what that place must have represented. “Just look at these structures right here. So strong and bold, built to last. I think it was called theatre. Maybe it was a place for miracle making and dreaming, where beings of all creeds came together to rejoice. Where all were welcome.” For white people, especially those with institutional power, ‘One Drop’ must serve as an inspiration and an urgent call for dismantling restrictive and exclusionary practices. For us, people who have historically suffered from racism, ‘One Drop’ serves as a reminder that when pushing for structural changes, we must remember to support, care for, and love each other. We must also continue to find ways to communicate and express creative ideas to foster the kind of love our bodies require to move forward. In that sense, Sonya Lindfors has consistently explored her craft to create collective anti-racist practices that simultaneously communicate love and action. I, and hopefully others too, left Tanssin Talo profoundly inspired to keep working to make the assumptions of the future humans come true.