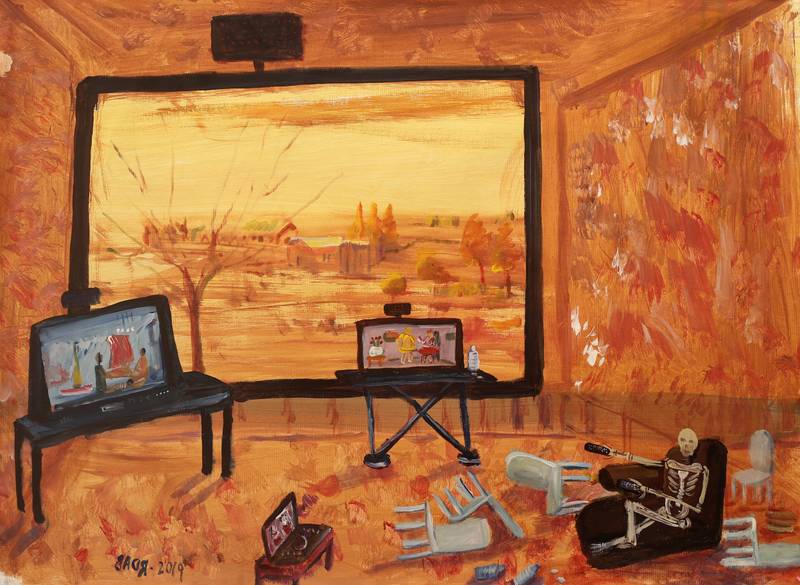

Ahmed Rabbani, ‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas, 2019

Natasha Malik is a visual artist and curator based in Islamabad, Pakistan. She sees curation as an extension of her artistic practice and is interested in the synthesis of art making and curation in the context of regional education, history, censorship, and social justice. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally.

Warning: Images and descriptions of torture in this article are extremely graphic

The Unforgotten Moon refers to Ahmed’s signature on his paintings, “Badr”, which translates as “moon” in Arabic, a loving nickname given by his mother. When signing his works, Ahmed deliberately inverted the Roman script of his name, a purposeful inversion symbolising the antagonistic reversal of human rights and laws experienced by Ahmed and other prisoners at Guantánamo Bay.

Between 2002 and 2023, the U.S. government held Ahmed Rabbani, a Pakistani Rohingya Muslim, without charge, first at the Dark Prison in Kabul and then at Guantánamo Bay, where he spent eighteen and a half years. During his incarceration, Ahmed made over a hundred artworks, eight of which were censored and confiscated1 by the U.S. military because they contained depictions of the imprisonment and torture he was subjected to at the detention camp. In 2021, Pakistani writer Fatima Bhutto introduced me to Ahmed’s human rights lawyer, Clive Stafford Smith, who wanted to collaborate with a curator to bring together Pakistani artists to respond to eight textual descriptions of Ahmed’s confiscated artworks, which Clive had seen and taken notes on during his legal meetings with him. Activated by this starting point, I began the project The Unforgotten Moon: Liberating Art from Guantánamo Bay in an effort to challenge and overcome the censorship and confiscation of Ahmed’s artworks.

In this project, I also participated as an artist, inviting artists Abdullah Qureshi, Amna Rahman, Amra Khan, Faraz Aamer Khan, Nisha Hasan, Sahyr Sayed, Shehzil Malik, Shehzad Noor, and Zainab Zulfiqar to respond to Ahmed’s paintings, vocabulary, and history. I had worked with many of these artists under an artists’ collective I founded in 2017 called The Creative Process, which involved participating in drawing and reading sessions, collaborating on exhibitions, and writing. While discussing the proposal with them, a few other artists joined the process due to a shared interest in the project. It was important that we collectively establish the sensitive and professional understanding required for such an undertaking. Beginning in late 2021, I scouted several private and public galleries and sites for nearly a year for the purpose of presenting the exhibition, but I could not find anyone willing to hold this exhibition. The recurring concern expressed by most people I approached was that the premise of The Unforgotten Moon could generate controversy and endanger their spaces, which were mostly privately run with little government protection. Although it was disappointing, I could comprehend this reasoning to some extent: spearheaded by a hybrid civilian-military government, citizens are chronically threatened by censorship in Pakistan.

On February 23, 2023, thanks to Clive’s tireless work, Ahmed Rabbani was released from Guantánamo and returned to Karachi. Abdul, his brother, also returned with him. In May 2023, we presented the exhibition with Ahmed’s paintings, which he brought back upon his return to Pakistan, along with the artworks made by the participating artists, at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in Karachi, Pakistan.

The Years at Guantánamo Bay

The post-9/11 era saw America’s revenge and paranoia in full force through its “War on Terror”. Four months after the 9/11 attacks, a high-security prison was built on the U.S. naval base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Since opening in 2002, Guantánamo Bay has become a symbol of injustice, abuse, and disregard for the rule of law. To date, around 779 men have been imprisoned there, many of whom have been held without charge and have been denied timely legal means to challenge their indefinite incarceration.

On September 10, 2002, during military dictator Pervez Musharraf’s presidential era, Pakistani authorities abducted Ahmed and his brother Abdul from their home in the middle of the night. At the time, Ahmed was working as a taxi driver in Pakistan, newly married, and expecting a child. The Rabbanis were sold to the Americans for $5000 after being classified as terrorists. The Americans were told that Ahmed was a known terrorist named Hassan Ghul. In In the Line of Fire: A Memoir, Musharraf wrote, “We have earned bounties totaling millions of dollars. Those who habitually accuse us of “not doing enough” in the war on terror should simply ask the CIA how much prize money it has paid to the government of Pakistan.” According to his memoir, 369 individuals were handed over to the United States due to Pakistan’s cooperation with the U.S. in its War on Terror post-9/11.

After spending 540 to 549 days2 in the CIA-run Dark Prison3 in Kabul, Ahmed was taken to Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. The U.S. Senate Report 2014 identifies Ahmed as one of seventeen detainees in the Dark Prison “who were subjected to one or more CIA enhanced interrogation techniques without CIA headquarters approval” and states that Ahmed “was subjected to forced standing, attention grasps, and cold temperatures without blankets in November 2022.” Two contract psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, to whom the U.S. government paid $81 million, developed Enhanced Interrogation Techniques for the CIA by reversing the ‘Survival Evasion Resistance Escape’ handbook, which was used by the U.S. military to train its soldiers to resist torture. These interrogation techniques were used on several detainees at Guantánamo to extract information about Al-Qaeda.

Shockingly, the Senate Report clearly states that soon after Ahmed’s abduction, the CIA knew exactly who he was: not Hassan Ghul, but Muhammad Ahmed Ghulam Rabbani. Ghul was captured in Iraq and held at the Dark Prison simultaneously with Ahmed. In a bizarre turn of events, Ghul was released after cooperating with the authorities in Kabul and, in 2012, was assassinated during a drone strike in Pakistan. Yet Ahmed continued to be illegally detained and rendered around the world to Guantánamo Bay.

By 2013, eleven years into abuse and detention without trial, Ahmed had lost all patience and started a peaceful protest by going on a hunger strike. The Istanbul Protocol allows competent protesters to starve themselves to death if they choose. Violating the protocol, also referred to as the ‘Manual on Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,’ the U.S. military amended the force-feeding methodology to make it gratuitously painful: “medical” staff would force a 110-cm tube up the protestor’s nose and pull it out for the daily force-feeding in what Ahmed recalls as the “Torture Chair”. Ahmed now finds any sensation in his nose intolerable.

The anger remains, which he admits makes life difficult for his family.

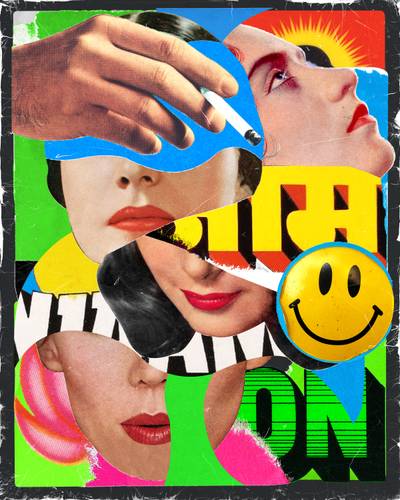

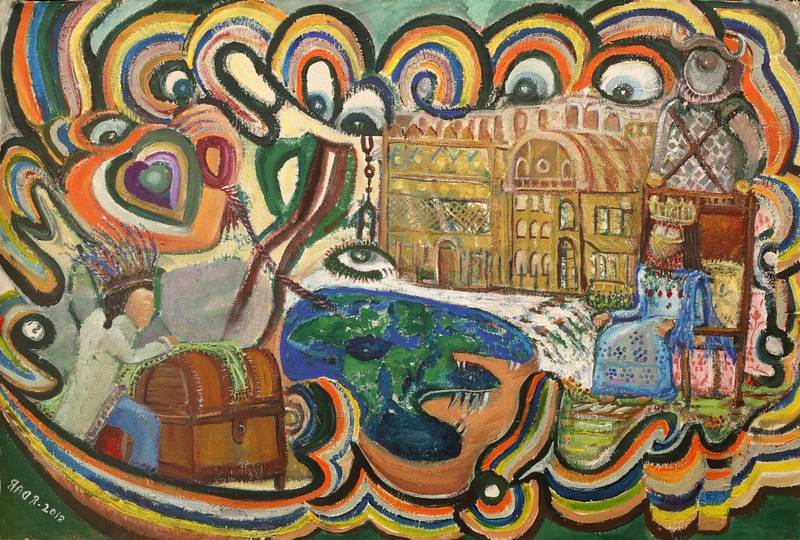

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas, 2018

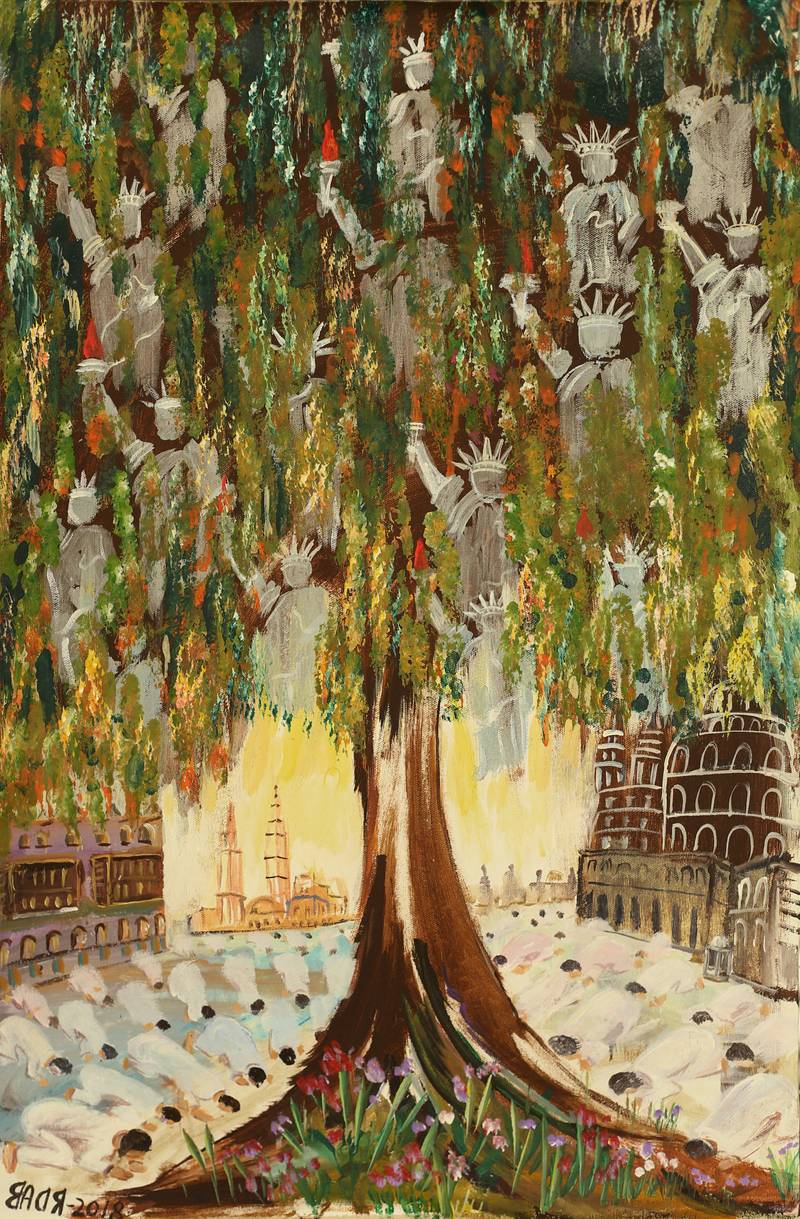

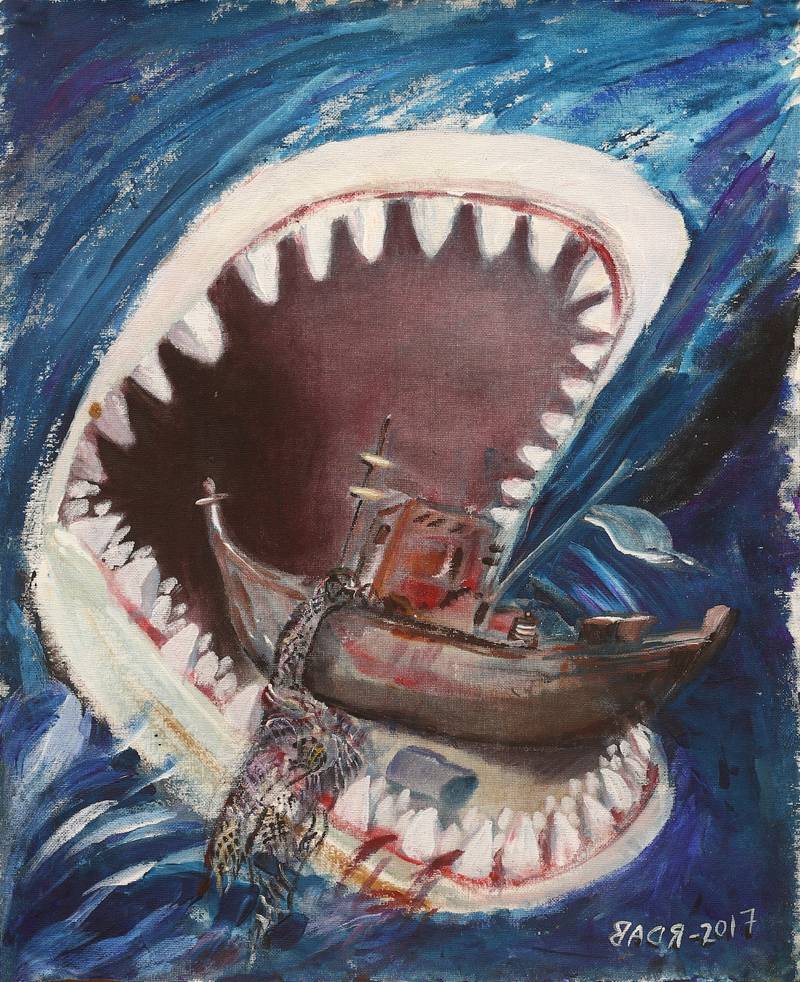

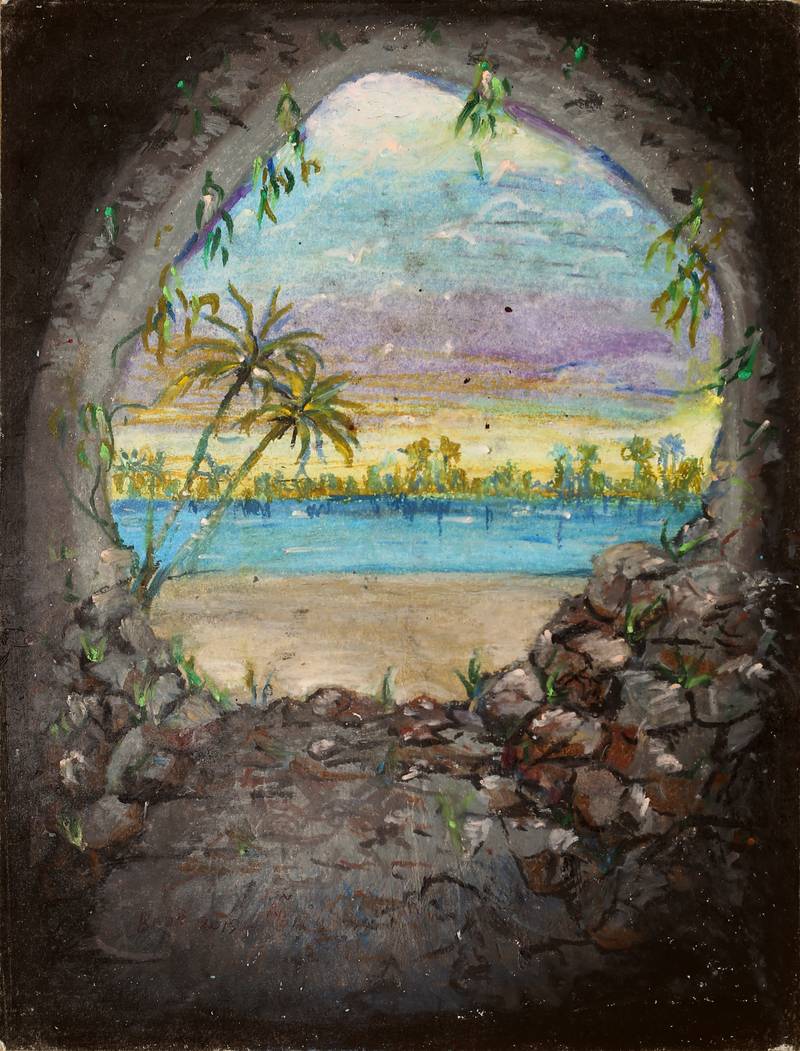

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas, 2017, from Ahmed Rabbani’s portfolio

Painting as a Form of Resistance

From 2009 onward, prisoners in Camps V and VI at Guantánamo, including Ahmed, could attend art classes. It was here that Ahmed began developing his art. Ahmed’s subject matter ranged from seascapes, landscapes, and still-life to religious iconography. His cell had no view of the outside—just a narrow strip of reinforced, opaque glass. Heavily censored television programmes, magazines, and a rich reserve of memories and imagination were his only windows to the outside world.

Any painting depicting torture or evoking prison-like spaces, such as images of chains, was confiscated as a general rule. Such works could not be sent to lawyers or the families of the prisoners. Each of Ahmed’s paintings that cleared the censorship process and were given to his family was stamped “approved by U.S. Forces”. Paintings not stamped with the U.S. government’s approval could not even be shown to family members during monthly video calls.

Making paintings in Guantánamo was often used as another tool of psychological warfare committed against detainees. It took years for Guantánamo to facilitate basic art materials; at first, they were provided only a single crayon to draw. Ahmed described how the guards used the opportunity of art classes to frustrate and “provoke” him and other prisoners; they’d burst in for random searches and take a prisoner to an isolation cell for no reason. There was always the looming threat that their paintings would be confiscated. Prisoners were not permitted to speak to each other during the art classes, and they were not allowed to take paintings to their rooms to complete them. Prisoners were not allowed to use more than one paintbrush or one colour at a time without permission. Every time paint or a paintbrush was needed, it had to be requested. No direct contact was permitted between the detainees and the art teacher during the art class. Only the guards could pass on materials to the students. If any materials were found missing during the class, prisoners would be strip-searched and placed in isolation as punishment. Sometimes, the harassment from the guards was so extreme that Ahmed could not paint and stopped attending classes for long periods.

Any painting depicting torture or evoking prison-like spaces, such as images of chains, was confiscated as a general rule. Such works could not be sent to lawyers or the families of the prisoners. Each of Ahmed’s paintings that cleared the censorship process and were given to his family was stamped “approved by U.S. Forces”. Paintings not stamped with the U.S. government’s approval could not even be shown to family members during monthly video calls. It is remarkable that Ahmed could paint after enduring such a purgatory of constant monitoring, punishment, deprivation, and cruel restrictions.

The difficulty of bringing public visibility to detainee artwork from Guantánamo was highlighted when, in 2017, Erin Thompson, an art crime professor, organised the exhibition ‘Ode to the Sea’ at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan, which featured artworks made by eight Guantánamo detainees, including Ahmed. The Pentagon reviewed releasing images of the artworks to the public due to the international media’s attention to this exhibition. Still, no artworks left the prison for a long time. The Department of Defence’s objection was based on where the proceeds from this exhibition’s sales were going. Professor Thompson clarified that the pieces for sale were only those of artists released from Guantánamo.

Ahmed created several paintings depicting his torture in the Dark Prison and at Guantánamo Bay during his detention. Preempting that these paintings would be confiscated, Clive, who had seen each piece in legal sessions, documented the imagery in text, each painting titled by him for reference. All notes taken by lawyers visiting clients in Guantánamo are classified and must be reviewed by Washington censors before being returned to the lawyers. Once made available to him by The Privilege Review Team4, Clive compiled his notes and shared them with the artists participating in The Unforgotten Moon.

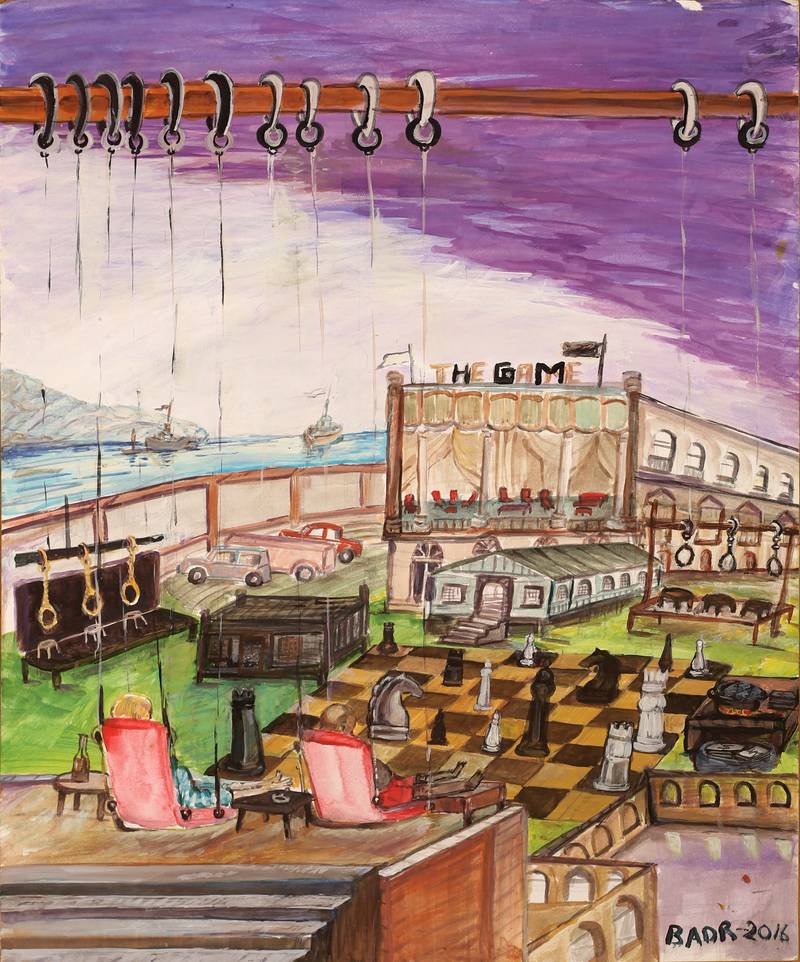

Transcribed from Clive’s notes on March 22, 2017, the text below describes ‘Games’, one of the confiscated paintings made by Ahmed.

“Chessboard w/ black + white chess pieces is in the centre. On the right, bags w/ dollar signs burn on a fire pit.

Chess board overlooks the gallows- three stools + three hooped ropes small green building/school house sits next to the gallows.

Behind the schoolhouse is a big stage, curtains open, red armchairs empty inside. The words ‘The Game’, bookended (?) by one white and one black flag, sit atop the stage. A jail with barred windows- all black- sits next to a chessboard. (to the left). To the left of the jail is another gallows- 3 stools, 3 ropes. Three vehicles parked behind the gallows and on the left side of the theatres. Overlooking chess board ---? Sign is a swing set w/ 2 red chairs- one w/ white person, one w/black/ a crown sits on the table between them. Wins sits on the table to the left of a white person who has a bottle of liquor-brown.

Both swingers have their feet up on small separate footrests (?).

The entire scene is enclosed by a wall, an ocean on the other side, and two large ships in the distance.

Dark purple sunset above all.”

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas paper, 2016. This painting is referred to as ‘Games’ in Clive’s notes

‘Games’ is exactly as Clive described it, but in person, Ahmed’s vision of the U.S. prison system, its policies around illegal and indefinite detention, and the painting’s apparent dark inversion of a TV show scene are all the more impactful. ‘Games’ is one of the confiscated paintings returned to Ahmed after his release and was displayed in the exhibition. What is the ‘game’ being referenced, who has engineered it, who are its players, and what are the stakes? Why was the painting perceived as a threat to U.S. national security, which led to its confiscation?

Painting was a form of resistance for Ahmed, a way to maintain and preserve agency and autonomy. Making art allowed him to escape into a world that only he could define. His artwork merged with his sense of self. Ahmed remembered his art teacher remarking that when he painted, he was not in prison, to which he responded:

میں نے بولا حقیقت ہے، میں ادھر ہی نہیں ہوں۔۔۔ میں جیل میں نہیں ہوں۔۔۔ ایسے میں نے سوچا ہے کہ میں جیل میں نہیں ہوں۔

“I said the reality is, I am not here. I am not in jail. I have made myself think that I am not in jail.”

Challenges and Undertakings in Building the Exhibition

Direct communication with Ahmed was possible only after his release in February 2023. Until then, we had just Clive’s text descriptions and access to Ahmed’s other paintings in Karachi via his son Jawwad. Each artist negotiated, rejected, embraced, and experimented with this material through the subjectivities of their visual language, which regularly surfaced, even as they tried to stay true to the text descriptions. We were navigating unknown territory, admittedly from a safe distance. There was an equal possibility that our work could unintentionally trigger Ahmed’s trauma. Building a sense of trust and conversational rapport with Ahmed was crucial in determining how to address such a complicated undertaking.

I met Ahmed for the first time in April 2023, at his home in Karachi, after he was reunited with his family. He was eager to share his vast portfolio; he had produced a significant series of paintings and drawings during his incarceration. Among them, only three paintings that chronicled the torture he had experienced in the Dark Prison and Guantánamo were allowed to leave Guantánamo with his release.

During one of our meetings, Ahmed expressed his grief about the artworks being held at Guantánamo. He felt those were his best works; if he got them back, he would never sell them. They were accurate depictions of his mental state at the time. He described one of his paintings, which he created using coffee grounds, as he had nothing else to paint with—hands and feet in chains and barbed wire. Another painting is of a clock that indicates the time in years rather than hours. On one side of the image, prisoners fight against time in Guantánamo, while on the other side, U.S. security agents push to extend it.

As artists who will likely never fully comprehend the magnitude of the challenges we know Ahmed faced (and will continue to face), attempting to give form to his censored paintings was an act of solidarity—to acknowledge and bring to public attention the physical and psychological horrors inflicted on detainees at Guantánamo, which the U.S. government and military actively prevent from reaching public awareness.

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas paper, 2016

The desire and urgency for them to be shared with a larger public remained a motivating factor in curating The Unforgotten Moon. Seeing Ahmed’s work in person, I was struck by the complexity and the capricious visual vocabulary of his paintings. With political currents and personal commentary running through symbolic landscapes, his work is a powerful insight into the conditions of the prison system and the psychological price of living inside it indefinitely. It was also important for Clive and myself that concrete financial support and visibility result from this exhibition. Hence, the project was designed as a fundraising exhibition where sales proceeds from all artworks would be forwarded to Ahmed and his family. The project’s process was organic, but the exhibition was contingent on Ahmed’s release, which kept getting delayed since being cleared for release in October 2021.

As artists who will likely never fully comprehend the magnitude of the challenges we know Ahmed faced (and will continue to face), attempting to give form to his censored paintings was an act of solidarity—to acknowledge and bring to public attention the physical and psychological horrors inflicted on detainees at Guantánamo, which the U.S. government and military actively prevent from reaching public awareness. Ours is among the many voices raised in response to the human rights violations at Guantánamo Bay, demanding that current prisoners be given due process and that artworks that are rightfully theirs be returned to them and allowed into the public domain if they so desire.

During this process, the artists and I attempted to find methods through which Ahmed’s censored paintings could be visualised and brought into the public’s imagination. We considered it important to question the agenda behind the censorship of artwork and what the so-called “threat” it posed to national security actually meant. Many of us responded to specific aspects of the paintings from Clive’s textual descriptions, while others attempted to replicate the descriptions as accurately as possible. The idea was to fill in for an absence by recreating the censored and confiscated artwork in the form of paintings, sculptures, installations, and music. With Ahmed’s consent, we were allowed temporary access to Clive’s legal notes and the Senate Report (2014), among other materials, and could thereby respond to Ahmed’s wider body of work, incorporating it into dialogue with our practices. This process helped explore and activate a vital link between the image and the materiality of language. As we continued to prepare for the exhibition, I showed Ahmed images of the other artists’ works in progress, to which he gave feedback.

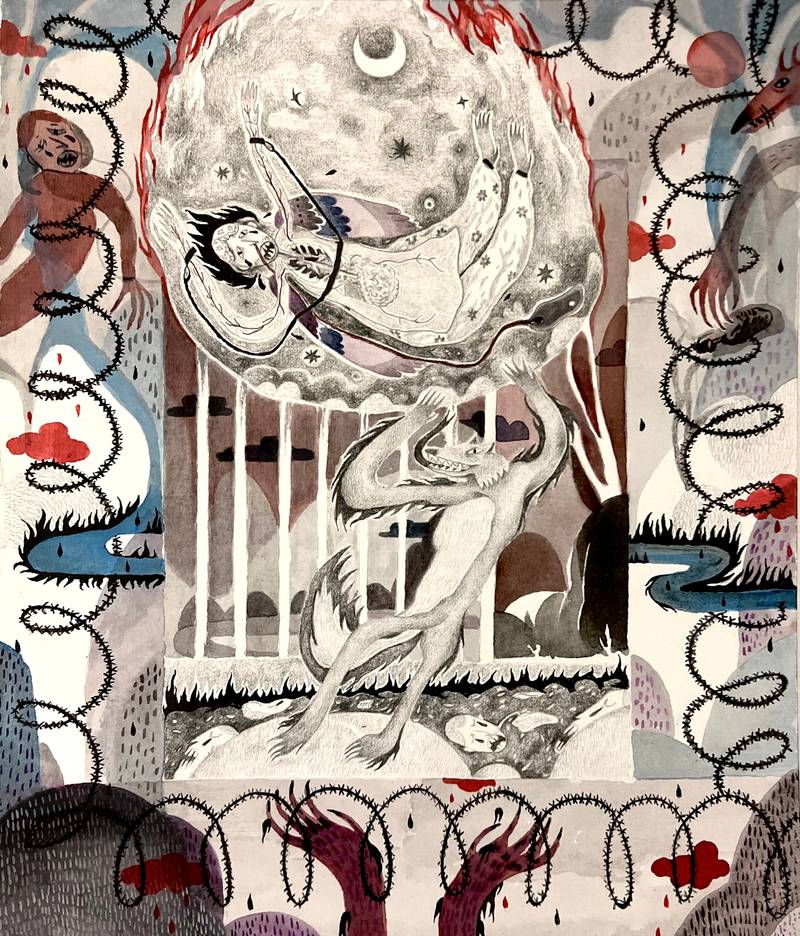

The artworks in the exhibition included Graveyard for the Living, in which Zainab Zulfiqar responded to Ahmed’s writing, which documented the abuse he experienced during his detention. This text was provided to them by Clive in the form of Google documents. Ahmed described the guards as “hungry foxes”, an allegory that Zulfiqar used to visualise the violence, pervasive hopelessness, and horrors of incarceration. The central figure—in a free fall, with bodily organs exposed and a tube going through his nose- refers to force-feeding during Ahmed’s hunger strike. Faraz Aamer Khan chose the text Reaching for Light and depicted a hand forcing its way out from under a scorched landscape, symbolising resilience. Evoking the compositional format of the triptych found in traditional Christian iconography, Amra Khan interpreted the text Strappado by painting a claustrophobic room with a lone figure with his arms forced into the Strappado position, a medieval torture technique.

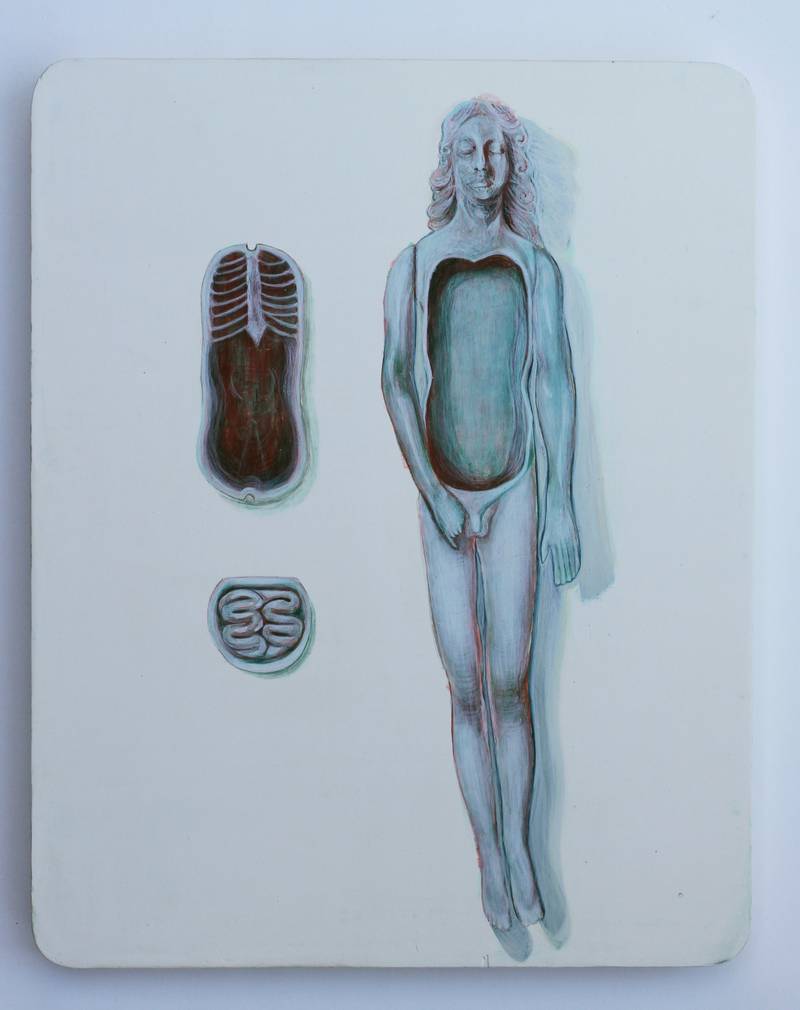

Responding to the text Chequered Single Cell Operation, Abdullah Qureshi isolates and enlarges the surveillance camera described, creating a chilling spectre in a black space. Nisha Hasan responds to Dining Out In Guantánamo Bay in her egg tempera painting titled Viscera; a deathly pale, hollowed-male body reminiscent of anatomy dolls floats in a white purgatory, conveying the body’s fragility and the effect of force-feeding.

Nisha Hasan, ‘Viscera’, egg tempera on traditional chalk ground (on beech wood), 2023

Zainab Zulfiqar, ‘Graveyard for the Living’, pencil, ink and gouache on paper, 2023

Abdullah Qureshi, ‘Camera on the Roof’, enamel paint on canvas, 2023

This process of interpretation posed several challenging questions. Is it possible to envision a wrongfully incarcerated person’s physical and mental realities without having experienced them in any capacity? Do we need to step outside our practice and lived experiences to acquaint ourselves with experiential material that is not our own and do so responsibly and sensitively? How do you define painting for someone who never envisioned a future for his art except that of making his present bearable? How do you look at his art, and what pre-existing expectations limit our perception?

Ahmed resonated with some artworks, not all, still found ways to relate to each piece, which he expressed at the exhibition opening. Referring to the exhibition opening, he said,

مجھے کل لوگوں نے پوچھا ہے ، آپ کون سےکلر استعمال کرتے ہیں ۔۔۔یہ ایکریلک کلر کانہیں ہے ۔۔۔جو ہم لوگوں نے اکیس سال دُکھ اور عذاب اور ہمارے خون، ہمارے پسینے ، ہمارے ٹورچرنگ ، ہماری اآئسو لیشن ، ہماری کڈنیپنگ ، جو ہم لوگوں نے گزارے اکیس سال ۔۔۔وہ چیز ہم نے ان کاغذوں میں نکالے ۔۔۔ایک بندہ جب باہر اِدھر پینٹنگ کرتی ہے ، یا کوئی بندہ کرتا ہے ، وہ پینٹنگ کرتا ہے ایک یعنی مطلب خوشی سے بنا رہا ہےکوئی چیز۔ ہم لوگ ، یعنی میں ، جو پینٹنگ بناتاتھا ، وہ حقیقی ، یعنی ایک ہمارے شعور ، ہمارے خیالات ، ہمارے دُکھ ، ہمارے عذاب ۔۔۔ہم پیپر کے اوپر ہم نکالتے تھے ، یہ کینوس کے اوپر ہم نکالتے تھے۔ یہ یعنی حقیقی مشاعرہ ہے ، یہ ہمارے آنسو ہیں ، ہمارے دُکھ ہیں، تکالیف ہیں ، اِس میں ہم نےنکالا ہے۔ یہ کلر ایکریلک کا نہیں ہے، یہ کلر اور چیز ہے، یہ روح ہے۔یہ روحانی کلر ہے۔

“Yesterday, people asked me, What colours do you use? I said that these are not acrylic colours… they are twenty-one years of grief and torment; our blood, our sweat, our torturing, our isolation, our kidnapping, what we experienced in twenty-one years… That is what I expressed on paper. When people outside paint, they create with happiness. We, or I, make paint out of reality, consciousness, thoughts, misery, and torment, and I take it all out on paper or canvas. This poetic reality, my tears, my sorrow, and my pain are what I took out. This is not acrylic colour; this is something else; this is a soul; this is the colour of the soul.”

Countering and Complicating the Status Quo

The detention system wields such power that it creates long-term stigma for the detainees, dehumanising them in the eyes of society. The events of Ahmed’s life since 2002 demonstrate an insidious, systematic desensitisation and detachment between those living in civic society and those incarcerated. He has returned to his family after a twenty-year absence as a sibling, father, and husband and is struggling with practical and financial restraints along with severe trauma from the past years. He is currently dealing with rehabilitation in a drastically transformed society. He has not received a Pakistani ID card since his release, which is essential for legal and societal survival. For example, he can live in Karachi but cannot open a bank account or obtain a driver’s licence. Such everyday yet enormous problems invite the question: how can we raise awareness and empathy to break down the stigma surrounding incarcerated people and demand a genuine and systematic rehabilitation and support system for these people? Furthermore, in Pakistan, how much power do citizens have to question and critique state narratives and actions around, for instance, giving up citizens to the CIA, post-9/11, for bounty money? Are we able to generate any accountability for what Ahmed has lost?

I believe artistic practices can challenge the habitual perception of incarcerated people and question the circumstances that legitimise their imprisonment. The exhibition’s collaborative effort sought to create communication and empathy, two aspects of life that prison systems routinely deny. In this sense, The Unforgotten Moon can be imagined as a meeting point for disparate worlds, finding common ground to create solidarity. This exhibition and the process leading up to it helped identify pertinent lines of inquiry more clearly that challenge and reveal the art world’s hierarchy and fears. I refer to hierarchy and fear in relation to the established system for “safe ways” of appreciating, evaluating, validating, and creating space for art as set forth by art institutes, museums, curators, writers, and critics. Artistic and cultural institutions must ensure inclusivity in their spaces.

Such everyday yet enormous problems invite the question: how can we raise awareness and empathy to break down the stigma surrounding incarcerated people and demand a genuine and systematic rehabilitation and support system for these people? Furthermore, in Pakistan, how much power do citizens have to question and critique state narratives and actions around, for instance, giving up citizens to the CIA, post-9/11, for bounty money? Are we able to generate any accountability for what Ahmed has lost?

A glaring gap exists between artistic practices in carceral and non-carceral spaces and the possibilities, or lack thereof, these allow. In her book ‘Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration’, Nicole Fleetwood writes extensively about prison art, invoking comparisons between the conditions of artistic production by nonincarcerated and incarcerated artists. Time and Space are experienced in vastly different ways by those existing within and outside the prison space. She writes, “Carceral aesthetics is the production of art under the conditions of unfreedom; it involves the creative use of penal space, time, and matter. Immobility, invisibility, stigmatisation, lack of access, and premature death govern the lives of the imprisoned and their expressive capacities.” ‘Penal space’ is the prison itself, the architecture of confinement, but the concept also refers to the disruption of family relations and domestic space, the imposition on movement and mobility, and the restrictive and highly monitored experience of the geographic, material, social, and psychic environments in which the incarcerated are warehoused, punished, and surveilled.”

The Unforgotten Moon revealed fundamental disparities between the artistic practices of “professional” or “free” artists and those of incarcerated artists. In my view, professional artists have a formal education degree or longstanding experience in the arts, maintain a studio practice, are affiliated with art and cultural institutes, and participate in the art market. The availability of resources, the relative ease of day-to-day predictability, and the “privilege” of “free” time are all conducive to thought and creativity for such artists. However, “privilege” has a completely different connotation for a prisoner. Ahmed emphasised that all privileges were provisional and subject to revocation by guards simply to ruin your mood.

In Guantánamo, there is no rights,

تمہارا کوٸی حق نہیں ہے، جو بھی وہ کر رہا ہے تمہارے لیے، جو تمہیں آفر دے رہا ہے وہ مطلب پریولج، ان کی مرضی سے جس دن دینا چاہتے ہیں وہ دیتے ہیں، جس دن منع کرنا چاہتے ہیں وہ منع کرتے ہیں، ہرچیزیں سے۔۔۔ مقصد ہے تمہارا مزاج خراب کرنا۔

“In Guantánamo, there are no rights; you have no rights. Whatever they are doing for you, whatever they offer you, that means privilege; the day they wish to give it to you, they will, and the day they wish to deprive you, they will, of everything… The aim is to ruin your temper.”

The formal training and trajectory of professional artists starkly contrast the life and work of an indefinitely incarcerated artist, who paints for self-preservation and survival and has no expectation of his labour being seen by the public. Ahmed, who invested time and energy working with me and whose openness and courage helped me understand his most painful experiences soon after his release, made me think about what the impact of The Unforgotten Moon may be. The answer may be revealed in time through continued dialogue with Ahmed, keeping his story alive through writing and media, and, when he is ready, extending access to a new network of people and support for future exhibitions of his work.

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas paper, 2016

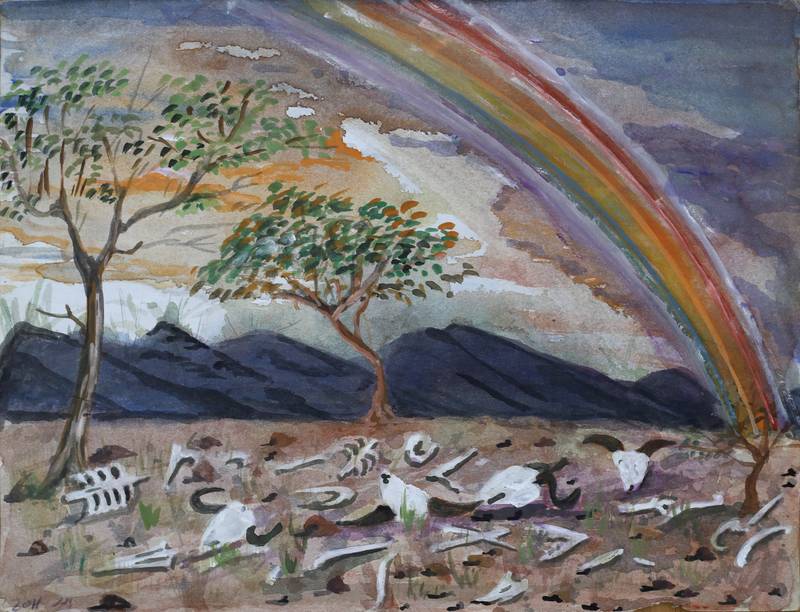

‘Untitled’, watercolour on paper, 2011

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas, 2019, from Ahmed Rabbani’s portfolio

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas, 2018

‘Untitled’, acrylic on canvas, 2017

‘Untitled’, oil pastels on paper, year not known

Ahmed Rabbani at the opening of ‘The Unforgotten Moon’ in front of ‘Strappado’ a painting by Amra Khan

Installation view of Ahmed Rabbani’s paintings from ‘The Unforgotten Moon’, Indus Valley Gallery, Karachi, Pakistan

Installation view of Ahmed Rabbani’s paintings from ‘The Unforgotten Moon’, Indus Valley Gallery, Karachi, Pakistan

Installation view from ‘The Unforgotten Moon’ exhibited at the Indus Valley Gallery, Karachi, Pakistan. (Left to right) Ahmed Rabbani’s painting palette, alongside works by Abdullah Quereshi, Faraz Amer Khan, and Natasha Malik

All paintings presented in the text by Ahmed Rabbani were exhibited at ‘The Unforgotten Moon,’ unless specified. All images are courtesy of Natasha Malik.