Still from •Tsutsue*, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

Mariam Osman is an educator with a master’s degree in intercultural Education, and minors in English Literature and Art Education from the University of Oulu. She is currently working in the field(s) of refugee and youth education and employment. Her interests included art, design, and the processes of knowledge acquisition.

Making feature-length films has always been a long and tedious process that requires abundant financial backing. No one knows this reality better than the non-Western filmmaker. To fund a dream project, one must adapt their vision to the preferences of foreign investors and producers. This leaves young filmmakers frustrated or in a position where they feel their artistry is being instrumentalized to sell an oversimplified image of their cultures and communities that doesn’t do much apart from satisfying the stereotypical expectations of certain Western audiences. While short films are not exempt from this reality by any means, they offer an alternative avenue for independent filmmakers to share their craft succinctly and, some may argue, more impactfully. Short films have recently offered many opportunities to break into the global market in a way that was not possible for some before, and with the increased yielding of film festivals such as Cannes, Berlinale, and Sundance, among others, to give space to new and exciting voices, a new generation of contemporary African filmmakers have arrived on the scene.

I’m writing this review through a lens of interest in the social, political, economic, and aesthetic state of our world and how these realities manifest in the everyday lives of the people who have been desperately overlooked; in the human condition and any medium that can adequately portray this; in dialogue and learning; and lastly, in the particular shifts that which we consume evokes in us, or if it evokes anything at all. With this in mind, let’s take a look at the short films presented this year.

To be human is to inevitably succumb

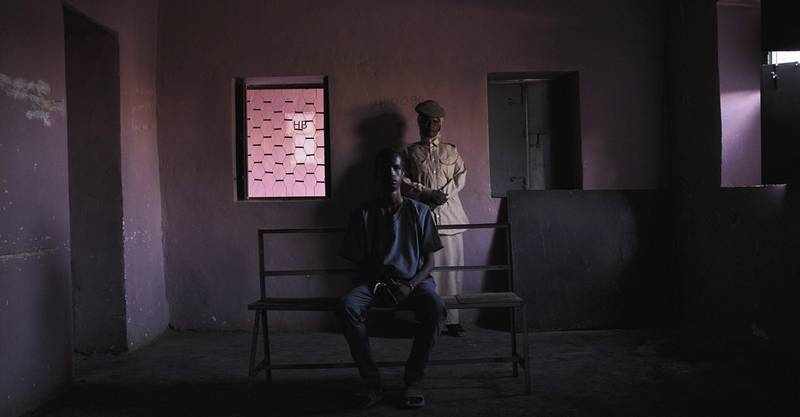

The longest feature of the African Express is Mo Harawe’s ‘Will My Parents Come to See Me’ (2022), which follows the progress of a young inmate through the Somali judicial system and his final moments on death row for unspecified (to the audience) terrorism charges.

An experienced prison officer stoically flanks the juvenile inmate throughout the scenes. The two mirror each other’s emotions and create a tension onscreen that leaves viewers both uneasy with the events about to unfold but unable to tear their eyes away from the screen due to its unavoidability. They play their roles as the detached inmate and indifferent guard without a hitch, the only crack in their armor being the former asking if his parents will come to see and the latter sitting alone in the dark when returning home.

Still from Will My Parents Come to See Me, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

Terrorism is a fraught, real-life issue that has been gripping the region for decades. One’s mind cannot help but fill in the blanks left unexplained as to the specifics of the crimes that have taken place. To anyone of diasporic Somali origin watching, the themes are familiar to us; these have been hushed stories of our country’s embattled history. While the film grants space to make your own judgements and refrains from presenting any binaries, it doesn’t absolve those watching into becoming complacent viewers. By methodically presenting the events taking place, the uniformity and repetitiveness of Harawe’s stylistic choices give way for aching emotions to arise at key moments.

At the climax of the film, things fall apart, and we are confronted with the last truth of being human. No neat procedures, maintained distance, feigned indifference, or legal speak can mask the ugly truth of death. Both our characters simultaneously succumb to their own realities; the inmate is reduced to begging for his life, while our guard finally breaks form and drives off in the middle of the execution without warning, El Wali’s "Youth of the Nation” blaring from the car speakers, the viewers realizing in this moment that she, and her feigned indifference, were the actual main points of the story.

Still from Will My Parents Come to See Me, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

‘Will My Parents Come to See Me’ offers some lasting questions: How do questions of religion and martyrship shape the individual story of terrorism? How are conversations surrounding capital punishment in our societies evolving? And what of the youth?

Grief in the face of filial duty

‘Tsutsue’ (2022) by director and writer Amartei Armar takes its rightful place as the visual standout of the bunch for its captivating and heart-wrenching scenes of a coastal town in Ghana that edges on a mountainous open-air landfill. The story follows Sowah and Okai as they attempt to come to grips with the untimely death of their older brother, Adjei, during a fishing expedition. Due to the tragedy, Sowah now has to grow up prematurely and take on the responsibility of keeping his younger brother in check as the now-eldest son of the family, a role his father harshly berates and reminds him of. Okai is left, meanwhile, to become preoccupied, if not troubled, with the loss and the seemingly unfeeling responses he receives from those around him.

Still from •Tsutsue*, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

Okai displays a willful stubbornness found commonly in the youngest member of any brood, one that will not bend to the rigidity of familial hierarchy. The parentification of Sowah and the translucently tough exterior he adopts in return contrast with Okai’s defiant obstinance. Idrissu Tontie Jr. (Sowah) gives a stunning performance, with a lingering shot of the camera enough to convey a depth of emotion impressive for his second time out. In the end, two things become clear: both Sowah and Okai have lost a main parental figure, which has rearranged their lives at a critical age, and in this new world, there is no more time to play hide-and-seek amongst the tonnes of plastic waste.

Make no mistake, ‘Tsutsue’ is as much a story of environmental failure as it is about familial obligation. Plastic and fast fashion landfills have been a barrier to the fishing community across coastal towns in Africa, and many have spoken out about the dangers that have been created by poor laws surrounding waste management. As far back as 2018, Ghanaian fishermen had reached out to news outlets to speak out about how the mishandled pollution crisis was threatening sea activities1. This not only meant that fish were disappearing from shores but that fishermen needed to tread rougher waters, which put them at increased risk of death. The fishing industry is also relied on by millions of Ghanaians. To this day, the U.S., Canada, and the European Union have offloaded “hundreds of millions of tonnes of plastic to other countries, where much of it may be landfilled, burned, or littered into the environment.”2

Still from •Tsutsue*, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

‘Tsutsue’ reminds us that there are countless real life stories where Africans bear the dehumanizing brunt of poor infrastructure, capitalism, colonialism, and ultimately, Western greed.

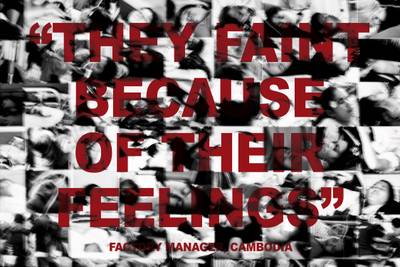

Sometimes silence is very loud

Dian Weys’ ‘Bergie’ (2022) gut punches with a force I feel I have not completely regained my balance from. The 7 minute film deals with the topic of homelessness on the streets of Cape Town. It’s perhaps by design that the horrors unfolding sneak up on the viewer when a 10km fun-run disintegrates into what can only be described as a total and utter lack of humanity. The film begins with us following a Marshal who is tasked with patrolling the morning race and removing any “hazards” on the road. We quickly learn the hazards in question are homeless people known locally as bergies, a term that is derived from the Afrikaans word “mountain”, a location in the town they frequently inhabit. After realizing that something is not quite right, the scene breaks out into chaos. The camera swinging back and forth shows us the ensuing chaos as the Marshal tries to simultaneously divert the race, follow legal procedure, and maintain any shred of dignity for what has taken place, all to no avail.

Oscar Petersen (the Marshal) delivers a poignant performance that is heightened by the use of a single-take throughout the film, a choice that leaves viewers with palpable tension as well as a deep outrage at the onscreen happenings, emotions that are grounded by Petersen’s apt display of bewilderment and what can only be identified as the cold realization of the human capacity for cruelty.

Still from Bergie, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

One stark failing of ‘Bergie’’, and director Dian Weys is the apparent unwillingness to touch on the issue of race in the wider conversation of homelessness and how our societies view suffering in relation to our many intersections. While the casting clearly points to a conscious divide here, further research of articles and press for the film offers no mention of the relationship race plays in regards to the theme of the film. While homelessness is a widespread issue in many communities, one cannot ignore the intricate systems built to affect some in specific ways.

An ode to our mothers

Jonelle Twum’s ‘I Think of Silences When I Think of You’ (2022) is poetry in the form of archival family footage and history spliced together beautifully. In just 9 minutes, we are taken on a journey through a wedding, a move overseas, and the evocative nature of silence. The short, which is part of a trilogy, details the voyage of Twum’s own mother from Ghana to Sweden in the late 90s, leaving behind all you know for unfamiliar territory. During the Q&A, Twum spoke of her mother expressing a detachment from the source material. What becomes of the dreams of our mothers when they are thrust into alienation—from themselves, from society, even from their own lives? In a conversation with Twum, we touched briefly on silence as performative and silence as productive: both concepts that challenge the underlying notion of silence as a negative connotation of the word.

Still from I Think of Silences When I Think of You, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

While ‘I Think of Silences’ is about Twum’s own family, it is also a representation of a larger community of women who come from similar backgrounds. There is not a lot of media out there that so melancholically touches on the experiences of African migration in the early to late 1990s, especially from the perspective of women. Diasporic viewers can identify themselves in this work in a way that feels very specific. The family photos of your mother posing by a large waterfall, crouched next to a bed of flowers, or in a midi skirt suit, young and settled in some European or North American city, not knowing previously of its existence before getting married, shown that on the other side of moving is sometimes a better life.

Twum touches deftly through her words on a daughter’s relational relationship to her mother. It is through measured, angry, knowing, and comfortable silences that we piece together the stories and dreams behind photos and videos.

The robot has come back to Goma!

‘Mulika’ by Congolese filmmaker Maisha Maene gives us an intro to Africanfuturism that is optimistic yet haunting. Nnedi Okorafor, a Nigerian-American author, coined the term “Africanfuturism” to describe a movement that seeks to replace Afrofuturism’s Western lens with one that is "specifically and more directly rooted in African culture, history, mythology, and point-of-view as it then branches into the Black Diaspora."3 With the increase in films coming out of Africa focusing on exploitation and extraction from a technological viewpoint, it seems wise to create a category that reflects and is rooted in this reality.

The film follows an “afronaut” as their spaceship crashes on earth and they climb out of what is said to be a mining crater; the real-life location is a recently erupted volcano, Mount Nyiragongo, on the outskirts of Goma. An event Maene took advantage of to create a beautifully suitable foreign landscape that leads our character onto the streets of Goma, a stark transition in a homemade spacesuit. On the streets, children and adults alike embrace our main character with a reverence that brings warmth to the gray and blue tones on the screen. Our protagonist poses for a photo, and as others gather, a man affectionately exclaims, “He’s a human just like me!” Later on, in a tent, the main character sits and is examined by two people who remark that his suit is made of the valuable mineral Niobium, used to make technological gadgets that they themselves would never benefit from.

Still from Mulika, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

In the end, our afronaut/robot/human encounters an elderly man, and it is here we see his face for the first time as he trades in his spacesuit for more spiritual garb and switches places in the cave with the man, the words echoing, “If today is the past of tomorrow, we can change tomorrow, and if today is the future of yesterday, we are already in the future.”

While it was personally difficult to connect with ‘Mulika’ during the initial viewing, aside from appreciating the stunning landscapes, the film benefits from a few rewatches and careful pondering on our need to aspire towards a new kind of liberation.

The kids will be alright

Masturbation has historically never been a popular topic of discussion in a myriad of overlapping spheres, including women, Africans, and certainly not teenagers. It is a beast many are left to tackle on their own, and for the youth of today, that means internet articles and BFFs through a screen as sympathetic guidance. Thus we get Sandulela Asanda’s ‘Mirror Mirror’, a no holds barred, coming-of-age film that deals with the important topic of female sexuality and pleasure.

Still from Mirror Mirror, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

We follow 17-year-old Luthando and Jodie as they chart their progress towards reaching the big O through a series of quick video calls. They lament a patriarchal society that has left them ill-equipped to fulfill their sense of bodily autonomy. Most of the short is brimming with tongue-in-cheek humor, some awkward acting, and a juvenile playfulness that is endearing. The standout scene is Luthando’s quick moment of somber reflection on her mother’s life and an existence she does not want to replicate, a scene that is certain to rouse a familiar ache in the chests of all African daughters everywhere. Though one must question our quickness to brand our mothers’ lives as wholly “miserable” because they do not operate, or cannot operate, on our understanding of female liberation. From the previous generation, a new one emerges, one that is unabashed to pursue fulfillment.

Still from Mirror Mirror, Image courtesy of Helsinki International Film Festival

While I wouldn’t say that this selection was the strongest of the group or an interesting note to end the screening on, it did offer an illuminating experience. Whether it was the subject matter itself, the fact that I was watching the film in a room full of other people, or both, I felt a deep sense of discomfort welling up inside of me. It spoke to the pinnacle of the film and the same reality as Luthando and Jodie that I had grown up in myself: female pleasure, or even the mention of it, is still a taboo topic, even now, even in the recesses of your mind once you’ve freed yourself from the shackles of the notion. While we have made some progress, some feelings are bound to stay imprinted within you no matter how much you evolve, and it’s good to be aware of that.

This year’s curation of short films in the African Express—Short Station touched on many connecting themes that lend themselves beautifully to the art of conveying critical stories through film. Overall, a very strong selection and a common thread in the works curated point to silences, known or unknown, around topics such as capital punishment, extraction, human rights, pleasure, and more. This reminds me of what is made clear about silence in Audre Lorde’s 1977 essay on “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action.” Whether we are silenced by others or silence ourselves, it is our own voice, and how we use it that will eventually free us in the end. What is urgent to us must be communicated and made clear by us; only then can we hope to free ourselves from the oppressive shackles of the unsaid. While Lorde was speaking here in speech, it can be true that film is also a worthy medium to speak our truth and can be a starting point for a call to action for viewers. A final point of reflection I left the theatre with was the echoing of Lorde’s pivotal quote: “What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?”4