KJ Williams. My Reality. Ink drawing. Image from PainExhibit.org.

Eva Tordera Nuño is a photographer and graphic designer born in Catalonia but established in Finland in 2004. She holds a master’s degree in humanities, focusing on contemporary art and culture. In 2020, she started her doctoral studies at the Department of Art at Aalto University, Finland. Her research focuses on chronic pain as an object that needs to be reconfigured outside the biomedical perspective and considers state-of-the-art knowledge on long-term pain.

Chronic pain is the most common disability worldwide1, causing its bearer to be summoned into a state of pain anticipation, worry, lack of decision-making, and even depression. Bearing chronic pain for years or even a lifetime is a life-changing event that affects concentration, sleep, moods and relationships. The impact of chronic pain goes beyond the individual level and is shaped by social and cultural factors. Every aspect of life is affected by this experience. Chronic pain is a notion created within biomedicine that reduces it to a biological process—dismissing the cultural, social, economic, political, and technological relations that shape it. As might be expected, this standpoint has not proven fruitful for its bearers or society at large. Bear in mind that chronic pain differs from a general understanding of pain because it is not merely a physical experience but has an all-encompassing sensory and emotional effect, as well as long-term transformations in the intellectual and agential capacities of the ones that bear it. And so, it is aggravating that the dominant culture, comprising an ableist gaze, stigmatises long-term pain bearers, as they are seen to be burdening healthcare systems without an objectively provable reason. Responsibility for management and recovery is placed on the individual, even though the social and economic domains primarily outline how this pain is experienced.

Through the ages, visual artists have shared experiences of pain through their works. Artistic representations of pain have revealed the link between physical pain and divine punishment, spiritual suffering, ritual practices and mental distress. In the twentieth century, artists such as Marina Abramović, Ron Athey and Bob Flanagan used pain as a provocation and their bodies as a site of protest in their performances. Encounters with artworks can emphatically affect how we understand even common concepts, such as pain, that we thought were familiar by proposing new ways to relate to them. When they do so successfully, it is because the knowledge they offer influences us enough to result in us questioning preconceived notions and conceptions. Existing knowledge of chronic pain is ever-evolving, and artistic representations of chronic pain have distinctly contributed to understanding several specific experiences of bearing chronic pain.

Why is Chronic Pain Different?

Human history is filled with mental, physical, or spiritual pain in every shape and form—self-provoked or induced by others. Pain, abundant in artistic and visual culture representations2, is also a powerful tool in physical public displays and tortures3. Pain is an intersubjective phenomenon that carries the cultural values, social perspectives, religious beliefs, economic realities, political views, and technological advancements that construct it.

Pain is classified as acute When it has a protective function and is predictable due to an injury, trauma, operation, or illness. Acute pain is a learning mechanism based on cause-consequence, a warning sign that the organism activates when it is hurt. It offers a biological benefit by provoking a response to avoid or prevent pain. Acute pain is temporary and disappears when the injury or damage is healed. Acute pain, thus, is always a symptom.

In contrast, chronic pain is persistent pain that lasts for more than three months and has since 2019 been classified as a disorder or a disease that cannot always be linked to an underlying condition, and it is usually not a sign of a threat to the organism4. By that classification, chronic pain is considered to lack a “function”. Yet, adopting a utilitarian perspective that sees acute pain as beneficial and chronic pain as not is ill-disposed to grasping the difficulty of living in persistent pain.

Chronic pain bearers cannot always cope with normative working life expectations defined by “productive ability”, as they cannot predict when and how intensely pain will strike. Chronic pain endangers the bearer’s life because of its personal consequences and also because chronic pain bearers are viewed as being “unproductive” to society, increasing the collective so-called economic burden. Lack of comprehensive understanding of chronic pain in workplace settings stigmatises chronic pain bearers as having “mental issues”, dismissing their pain as a merely psychological concern.

Gauging chronic pain through the parameters of acute pain does not help in comprehending chronic pain. Acute pain can be diagnosed with certainty by identifying a broken bone, tissue damage or neurological injury. Chronic pain seldom can be measured other than by asking the bearer how much their pain can be quantified on a scale of 0 to 10 and trying to grasp the kind of pain they experience: Does it feel like knives? Is it throbbing? Itching? Or like electrical shocks?

Chronic pain’s multidimensionality makes it complex to diagnose, treat and live with, even though it is the most common cause for someone to visit the doctor5. More often than not, chronic pain cannot be diagnosed by a test or through imaging such as X-rays, ultrasound, CT scans and MRI. Its bearers face difficulty proving their pain because biomedicine, which focuses on the body’s biological functions and organs, may not acknowledge experiences that cannot be viewed, touched, demonstrated, localised or measured.

General practitioners and primary health care professionals rarely have specific knowledge about chronic pain. Despite being the first disability worldwide6, and between 20–30 % of the world’s population suffering from chronic pain7, very few countries have chronic pain-specific protocols and management strategies8. Incomplete knowledge of chronic pain raises doubts about the dependability and capacity of biomedicine to diagnose and treat it. It challenges the scientific method because each body is unique, and there is no universal solution. The lack of pain-specific protocols in palliative care units designed for terminal illness means that chronic pain patients do not receive effective relief from palliative treatments because these are not intended to treat their pain.

Chronic pain bearers cannot always cope with normative working life expectations defined by “productive ability”, as they cannot predict when and how intensely pain will strike. Chronic pain endangers the bearer’s life because of its personal consequences and also because chronic pain bearers are viewed as being “unproductive” to society, increasing the collective so-called economic burden. Lack of comprehensive understanding of chronic pain in workplace settings stigmatises chronic pain bearers as having “mental issues”, dismissing their pain as a merely psychological concern.

The complexity of chronic pain can be understood through three key components: (i) the sensory component is responsible for the acknowledgement of pain being experienced; (ii) the emotional component produces an aversion to the feeling of that pain; and (iii) the cognitive component involves the existential response to the pain sensation, requiring self-consciousness9. All pains affect the sensory and emotional dimensions, but chronic pain profoundly impacts the cognitive capacities of the bearer10, resulting in a lack of concentration and memory loss from bearing pain for a prolonged period.

During my three years of research on chronic pain, I have developed the term ‘bearer’ to refer to people who suffer from chronic pain. Suffering is a way to describe their experience. ‘Suffering’ and ‘pain’ are often interchangeably used, even though they are classifiable – one can suffer from a broken heart, from the death of a loved one, from a traumatic experience that endangers the person’s integrity, and from pain in one’s soul. ‘Bearing pain’ is like carrying a heavy load that can sometimes feel lighter or heavier but is always there. The term ‘bearing’ captures various aspects of the chronic pain experience, including how a person stands or moves, their tolerance, relevance, awareness and relation to their environment. ‘Bearing’ also refers to how much weight a structure can support before giving up. These meanings highlight the complexity of chronic pain, all centred around the person experiencing it. Unfortunately, chronic pain remains misjudged, bringing the lives of its bearers frequently to the brink of suicidal feelings11.

In such a misjudged premise, how has art participated in discerning what chronic pain truly is? I will clarify this question by delving into two artworks that represent the knowledge existing on chronic pain at the time of their creation. Looking at them will help portray the brief history and context of this multilayered phenomenon.

What Can Art Offer?

Artistic representations of chronic pain usually depict the physical, physiological and sensory dimensions of the experience and effect of such pain. Since our situated knowledge12 shapes our perceptual experience of artworks, we easily relate to such artworks, given that most of us have some foreknowledge of injury and pain.

Through the following examples, I will focus on two distinct artistic representations of chronic pain to further understand both the limits and needs of such representation and to outline chronic pain as an intersubjective experience with sensory, emotional, and cognitive components that may primarily be accessed through the lived experience of its bearers:

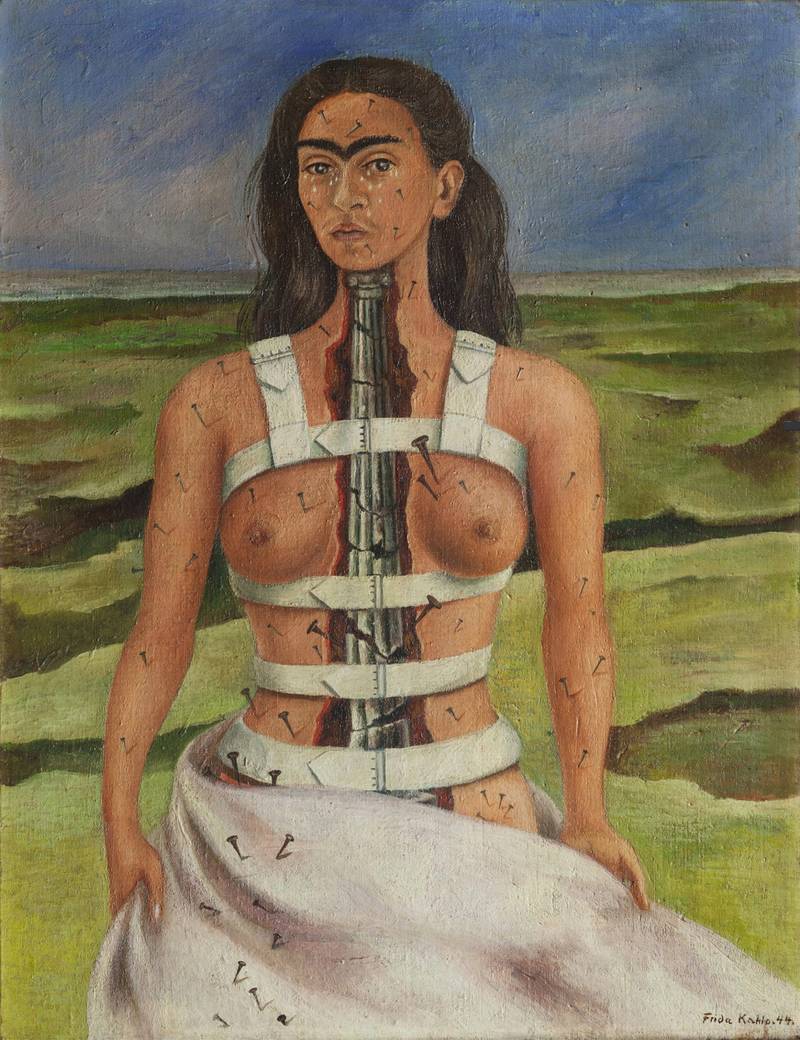

The Broken Column (1944) by Frida Kahlo

In 1944, Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) painted the self-portrait The Broken Column. She stands before a bare landscape; her upper body is cut open, and a crumbling Ionic column replaces her spine. Different-sized nails stab her skin, and the metal corset she wears keeps her upright. Although tears roll down her cheeks, her expression is controlled and serene. The pain Frida Kahlo felt throughout her life must have been, in many cases, excruciating, as she suffered from spina bifida13, right leg deformation due to poliomyelitis, and a spine and pelvic injury due to a tram accident when she was eighteen years old. Her body was the site of thirty-two surgeries14 and two amputations. Frida Kahlo expressed her pain in numerous artworks, but in The Broken Column, she focused on the enduring pain that persisted from the time of her traffic accident until the end of her life. At the time of this painting, she had been bearing pain for twenty-eight years.

The Broken Column (1944). Frida Kahlo. Oil on masonite. 39.8 x 30.6 cm. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico City, Mexico.© D.R. Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo.

Medically speaking, at the time of this painting, Frida’s pain was this: just pain. Around the 1940s, pain clinics did not yet exist, and as a term, chronic pain did not appear in medical journals, leaving most of its bearers outside medical history15. After World War II (1939–1945), interest in ongoing pains rose, as many war veterans suffered from chronic pains after injury and many developed phantom limb pain due to lost limbs. Doctors could not cure them as there was no explainable cause, such as tissue or nerve damage. The need to care for those who suffered after they had defended the nations drove advancements in pain treatments and the imperative to comprehend the mechanisms of persistent pain. John J. Bonica, an anesthesiologist at the Madigan Army Hospital in Fort Lewis, Washington, initiated the field of pain medicine and coined the term ‘Pain Clinic’. Bonica’s novel approach to addressing pain demanded a collective effort to shift it from private suffering to collective responsibility16.

Frida’s medical case fit the prevailing notion of pain in the 1940s, where (chronic) pain was regarded as a symptom of an underlying issue requiring explanation and proof. This understanding emerged from the biomedical framework of Western medicine, known as biomedicine or conventional medicine, a powerful and all-encompassing concept fundamental to health science and technology endeavours in academic and government settings. It represents a set of philosophical commitments, a global institution woven into the fabric of Western culture and its power dynamics, and more17. The principles and practices of biomedicine influenced Western medical practices and the broader healthcare infrastructure, determining how healthcare is provided and experienced.

After World War II, industrialised nations allocated increased funding to medical research, widespread access to health insurance, and a significant pharmaceutical industry expansion. Governments supported these changes in most Western countries18, making biomedicine integral to welfare society and capitalist ideals. Consequently, it spread its wings by assimilating other medical traditions. In biomedicine, the bodily organs and functions are often separated and inspected as units of knowledge. Thinking that by understanding the parts, the whole can be reconstructed, healed, or understood is a reductionist temperament, especially in the case of chronic pain. Chronic pain experiences are embedded within specific cultures and societies, affect individuals, and are mediated by power dynamics and systemic flaws.

In the 1950s, the first hypotheses addressed the mechanisms behind chronic pain, its multidimensionality, and potential therapies. In that decade, the term chronic pain started appearing in medical journals and became widely used in the 1970s19. Due to the incomplete, incorrect and fragmentary knowledge at that time about chronic pain, doctors misdiagnosed Frida Kahlo’s spine injury as the cause of her pain. She underwent several painful and unsuccessful operations to ease her agony and became addicted to morphine, a commonly prescribed aid for pain at the time. The hypothesis nowadays is that she experienced chronic neuropathic pain20, fibromyalgia21, or Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)22, which would have required very different types of treatments, as opioids are harmful to chronic pain patients and surgical procedures can be detrimental.

Eugenie Lee’s Seeing is Believing (2016–2019)

For over a decade, artist Eugenie Lee has been working on chronic pain, drawing from her experiences as a pain bearer. In her works, she conveys the sensation of pain by combining her personal insights with neuroscientific research findings. Aware that in present times, technology mediates our relationship with the world, she uses it to mediate our relationship with chronic pain.

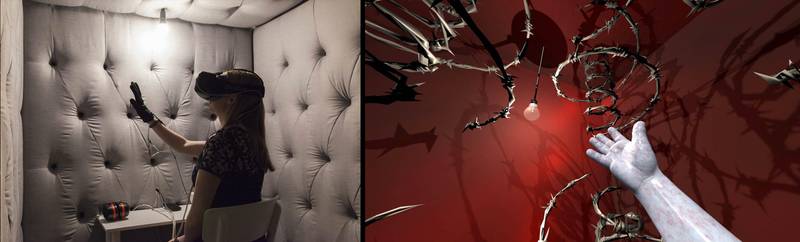

Lee’s Virtual Reality (VR) participatory performance installation Seeing is Believing allows participants to get closer to the experience of CRPS using artistic concepts and processes to complement scientific knowledge, creating a three-stage interaction that brings the participant in touch with some chronic pain symptoms simulated by illusions.

(L to R) image from the anechoic chamber of Seeing is Believing and VR scene of a participant’s hand. Images from Silversalt Photography and Andrew Burrell.

In the first stage of the installation, the participant experiences physical discomfort induced by the Mediated Reality MIRAGE Machine. The MIRAGE machine is an illusion device with a screen and camera system that modifies real-time video capture to create a false perception. Furthering the mirror technique, neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran developed this machine to ease the pain of the phantom limb when he understood that visual feedback could help alleviate pain and improve motor function. Lee’s participant places both hands under a screen, and their hands appear on the screen in real-time. Lee then touches the participant’s hand, and they both feel and see the touch, establishing a connection between physical and visual perceptions. Next, the participant feels Lee’s hand grab one finger while on the screen, the finger lengthens a few centimetres. This combination of touch and visual sensory input creates the illusion of a deformed finger, which causes discomfort. Other illusions involve shrinking the finger or mistaking the right hand with the left. In the first stage, Lee manipulates the participant’s sensory stimuli to experience a phenomenon that physically does not exist. In this way, participants experience how their perceptions can be misleading, which connects to a neuroscientific explanation of chronic pain.

In the second stage, Lee invites the participant to enter a relatively small, acoustically isolated, and sound-absorbent space that limits their sensory experience. Inside, the participant wears an Oculus Rift set (VR glasses and headphones) and an interactive glove formed by two gloves. One glove with sensors records movements, and the other provides a sensation of heat and small vibrational stimuli. In this virtual reality setting, the participant is introduced to a scene where they experience their hand being inflamed and pierced by a barbed wire and can experience pain or some physical sensation of discomfort, even though they know that nothing is physically harming their hand. In the third stage, Lee evaluates the participant’s experience, explains the scientific basis of the artwork, and acknowledges the contributors’ responses.

In this one-way installation, the participant cannot influence what they see but only experience it. This encounter allows them to understand pain that doesn’t physically exist. They embody pain that cannot be shared or mastered. Lee designed this participatory performance to simulate some symptoms of chronic pain—not only the physical sensations of pain but also emotional distress, lack of control, isolation, anxiety, vulnerability, and anticipation23. Participants have varied experiences; some vividly feel the illusion of hand manipulations, and some do not get tricked. Nearly every participant comes away “with an altered perspective on what persistent pain is about and on the responsibility as members of society—that what we do, say, and behave towards others, including people living with pain, has a ripple effect.”24

Lee brings physical pain closer to people unfamiliar with it using one-to-one interaction, performance, and VR. Combining scientific knowledge, personal experience, artistic expertise and technology, the installation shows that the brain can perceive pain without a physical cause. Lee aims to familiarise the participants with the experience of pain and create empathy for those living with constant pain, making the experience relatable to people from all backgrounds.

From Artistic Representations to Medical Realities

The Broken Column is an enduring representation of how Frida felt after almost three decades of pain. The steel corset allowed her to sit upright without being tightened to a chair. The image conveys her strength through pain and suffering. The deserted landscape is symbolic of the isolation experienced by the chronic pain bearer, whereas nails, tears and the crumbling of the column represent her pain. Experiencing pain for a prolonged period places the pain bearer in a liminal state of existence.25 Due to inadequate explanations and objective reasons for one’s suffering, its bearers are dismissed, stigmatised, and displaced into unrecognition.

Conversely, Seeing is Believing brings together contemporary knowledge of chronic pain to offer visitors a detailed and specific understanding of the complexity of prolonged pain experiences. Deriving from advancements in the biomedical field, Lee incorporates VR therapies and external brain stimulations to rewire the brain by forcing it to focus on experiential stimuli via VR or electrically modifying neural circuits in hospitals for cancer and post-surgery patients.

The first problem is equating chronic pain to a mechanical problem that is condensable in an image; the second problem is the attempt to achieve characterisation through oversimplification, which reduces the experience to a specific sensation and moment in time. The third problem is that art therapy, although undoubtedly valuable as a therapeutic tool, does not help expand the knowledge of a multifaceted phenomenon such as chronic pain.

In the eighty years since The Broken Column, there has been no significant progress in how pain is depicted. Little has changed when trying to represent such an overwhelming experience. Artist and researcher Deborah Padfield has been assisting the communication between patients and doctors by creating visual representations of chronic pain26. Padfiled’s collaboration with bearers has created a visual vocabulary that helps patients and clinicians communicate. These images are attempts to express the feeling of pain. Unfortunately, despite acknowledging the valuable aid these images offer the patients, chronic pain’s multilayeredness cannot be amply comprehended only by looking at images like those that patients can create in art therapy sessions.

These days, specialised pain clinics’ treatments acknowledge chronic pain’s multifaceted nature and effects by planning interdisciplinary approaches that combine pharmacology, physical therapy, medical procedures, acupuncture, VR, cognitive behavioural therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and mind-body techniques such as meditation. Chronic pain management is intended to be provided by a doctor (usually an anaesthesiologist), a nurse, a physiotherapist, and a psychologist. These approaches do not always offer results, and the patients seek help in more holistic approaches such as Chinese medicine and complementary and alternative therapies that focus on the person, not the symptoms.

Nowadays, biomedical and neuroscientific research better understands the mechanisms behind pain and the impact of chronic pain. A recent example is the Pain Exhibit website, where artists and chronic pain bearers explore visual representations of chronic pain. These interventions are valuable in that they help the bearer express a terrible sensation that dominates their lives. When channelled through an image, there is a feeling of control and agency in making an intimate sensation visible to others. Expressing pain through images may summarise a specific sensation, but can they work as openings towards complex experiences? Elicitation of physical sensations, if represented concretely, can assist communication between patient and medical practitioner. Still, the experience of chronic pain surpasses the physicality represented in these images and extends far beyond the slice of time seen in these visuals.

The limitations in how these images communicate pain are manifold and can be understood as ‘cognitive glitches.’ This is because they manage to represent the sensory and sometimes emotional components involved in the pain experience but not the cognitive components, thereby equating chronic pain to acute pain. Such equating leads to several obstacles when trying to understand what chronic pain is and how it functions: the first problem is equating chronic pain to a mechanical problem that is condensable in an image; the second problem is the attempt to achieve characterisation through oversimplification, which reduces the experience to a specific sensation and moment in time. The third problem is that art therapy, although undoubtedly valuable as a therapeutic tool, does not help expand the knowledge of a multifaceted phenomenon such as chronic pain.

A Call for Participatory Art Experiences

Works of art that necessitate a participatory space have the potential to create a nuanced understanding and distribute knowledge about chronic pain. Only by creating spaces for sharing the complexity of bearing chronic pain can there be new provocations for sensory and emotional reactions, which can stimulate new, updated and required ways of understanding the world.

Since most of us have experienced acute pain at some point, the threshold for understanding chronic pain without having experienced it ourselves is high. Thus, the tendency to extend the foreknowledge of pain to an understanding of chronic pain is, at best, through the visible. For example, when you see The Breaking Column, your muscles tighten, and your attention is drawn to the support that maintains Frida Kahlo’s posture. Instantly, you contemplate the crucial role of the spine, the backbone that anchors your body. As it happens, the phenomenon represented in Kahlo’s painting is more complex and is closer to the experience that Eugene Lee’s Seeing is Believing brings to its participants. Chronic pain is not a given condition but a comprehension of invisible, immeasurable, individual, and intersubjective experience with sensory, emotional, and cognitive components. It can be understood as a disability hinged on how much of society and its living and working conditions are built on the concept of ableness. In many ways, chronic pain is an experience lived in the first person, but it is configured by all aspects of life: social, economic, political, cultural and technological.

Artworks that try to represent the feeling of pain by focusing only on the sensory and emotional aspects are reductive and offer nothing beyond the chronic pain conception of the 1940s. Limiting the representation of pain to how it feels keeps the status quo of understanding chronic pain as any pain, which is counterproductive when trying to explain such a complex phenomenon that involves all aspects of the bearer’s life and environment. Passive representations of chronic pain do not encompass the components that make chronic pain such an abominable experience. They do not surpass the existing conceptions of pain; thus, these representations fall short and leave us with an untouched association between the acute pain experience.

Works of art that necessitate a participatory space have the potential to create a nuanced understanding and distribute knowledge about chronic pain. Only by creating spaces for sharing the complexity of bearing chronic pain can there be new provocations for sensory and emotional reactions, which can stimulate new, updated and required ways of understanding the world. Because the components of chronic pain are sensory, emotional and cognitive, the components of our participation, experience and understanding should be activated by an artwork that attempts to represent it.