Portrait of Saara Ekström by Sabina Westerholm

Taru Elfving is a Helsinki-based curator and writer focused on nurturing undisciplinary and site-sensitive enquiries at the intersections of ecological, feminist and decolonial practices. As artistic director of CAA Contemporary Art Archipelago, she is currently developing a multidisciplinary research programme on the island of Seili in the Baltic Sea.

We began this conversation on a train platform in Turku, where we ran into each other on our briefly intersecting journeys. We continued online to talk about Saara’s recent exhibition, Through the still eye of the storm at Taidehalli Helsinki (June-August 2023) and her exploration of time that has evolved through her practice for nearly thirty years. We returned progressively to the conversation over the phone and via email in a deliberate search for words in sync with the cyclical, slow unfolding that informs and characterises Saara’s approach to urgent matters of change.

TARU: Your solo exhibition at Taidehalli focused on the materialisation, embodiment and entanglement of different temporalities and cycles of change. I know that you worked on this exhibition for several years, and it was densely layered and complex, but please introduce this exhibition briefly. The starting point for the exhibition was geological deep time – the gradually evolving events starting at the birth of our planet – and our existence in relation to these immense dimensions. It was born out of a desire to emerge in extremely slow processes, partly in reaction to restless times, but also to search for our connection to nature and to nourish our ability to imagine.

SAARA: There is something comforting and frightening about massive time scales that we cannot comprehend with rational thinking. We feel small and insignificant, us humans being just a singular era and layer in the future sediments to come. So, geological cycles were one way to approach this vast arc of history that shaped the world – and us. The core work of the exhibition became a 16mm film titled Geopsyche, filmed over a span of five years in Iceland, Spain, Sweden and Finland. It is a meditation on the layers of knowledge and information amassed over millions of years in the earth’s stony chronicles. The other works – photos, clay paintings, bronze sculptures and film installations – spawned from the film and the thoughts and emotions it put in motion.

In my attempt to give form to the passage of time recorded in geological formations, I also needed to explore our relationship to these structures. What kind of connection does a human have with a landscape? How are the world creation myths born? Why do certain places, such as mountains and caves, stir archaic memories even in our modern minds?

Geopsyche, 2023, 16mm film, duration: 23 minutes | Photo: Saara Ekström

You worked in different places during this process, so would you say that the works in their diverse media were also born out of these specific environments? Or that certain landscapes make certain approaches or perceptions possible? The otherwise rather abstract questions about time become thus situated in the works.

Yes, absolutely. I started filming material for Geopsyche on Källskär, a small island in the outer Åland archipelago between Finland and Sweden while working in an artist residency there. The island is known for its strange, evocative formations carved in the cliffs by the retreating glacier over 10,000 years ago. It became a daily ritual to visit the cliffs, see how the sun illuminated these forms from slightly different angles and listen to the dark voices of their shadows. It was a cosmic dance between a small planet and a gigantic hot globe of glowing gases. I became spellbound by that island.

To get closer to those voices, I had to go deep underground and, on top of it, searching for openings between the above-ground and the below-ground to reach the subterranean, both in our consciousness and under our feet. So, parts of the work were filmed in Spain in the mystical Nerja caves, where early humans left their marks, and parts in Iceland, where a volcano at Fagradalsfjall started erupting while I was busy with the work. All these sites offered new angles to the concept of time, but also to many other topics. They were profound encounters, enhanced by the fact that I often travel and work alone. What was important was to share these experiences to connect with others through these places and images.

This is a good example of how I often work, collecting material over several years, eventually sticking the pieces together, and seeing a form emerge. I like to keep the creative process open for as long as possible, giving space for the work to develop both spontaneously and through planning. There is not necessarily a narrative ready in the beginning; it grows while you proceed and wait for things to appear on your radar.

The exhibition Through the still eye of the storm consisted mainly of new works but also included some older pieces, like resurfacing memories or recontextualised past moments. What is the role of time, cycles and returns in your practice?

Combining new works with older ones is one way of communicating with the past, trying to see if there’s a red thread going through years of artistic practice and personal changes. Interesting things start happening when the works connect, and new meanings and associations emerge. It’s like creating a new piece or playing a puzzle with many possible outcomes.

This is a good example of how I often work, collecting material over several years, eventually sticking the pieces together, and seeing a form emerge. I like to keep the creative process open for as long as possible, giving space for the work to develop both spontaneously and through planning. There is not necessarily a narrative ready in the beginning; it grows while you proceed and wait for things to appear on your radar.

Looking back at earlier works, I see returning themes, such as the fragility of our lives, cycles of growth and death, and the destructive and nourishing power of time. I’ve moved from filming organic materials, rotting plants and blooming flowers to more complex matters, such as architectural structures, buildings with historical significance and buried meanings. Even if they seem far apart at first glance, these works circle the same topics: memory, oblivion, change, collapse, and growth. They complement each other. Intimate and private intertwine here with the collective and shared.

One of the purposes of exploring these subjects is to see the concealed, such as our mortality and sexuality, things we classify as dirty and unwanted, and past events we wish to forget. This is very revealing since matters pushed to the edges of perception tell a lot about our fears and desires.

Secret Empires, 2023, digital time-lapse animation

Limbus I, 2011, C-print

The human body is not usually explicitly represented in your work; instead it often has a haunting presence in the most surprising formal and sensory resonances. Your enquiry into different temporalities does not erase the human and the lived present. How do you see this?

It has been important to try to grasp our (human) position in connection to these massive geological events, and the only way to get closer is through my own body and mind. From this point of view, I see the film Geopsyche not only as a way to explore geological events but also as a metaphor for the birth and development of the human subconscious.

We have this prehistoric darkness within us that we have difficulties coming to terms with. Film director, poet and author Pier Paolo Pasolini approached it successfully, as did film directors Tarkovsky and Weerasethakul and poets Eeva-Liisa Manner and Dylan Thomas, to name a few. It’s difficult in many ways to penetrate these layers since you must dig deep, but it’s worth a try. I feel like a novice, but I know that, in a way, you need to carve a tunnel through yourself, and it is both painful, scary and blissful as you push further.

It’s quite amazing that our bodies are already intimately familiar with earlier lifeforms as we relive the evolution in our muscles and organs. For instance, so-called archaic muscles are visible in the early stages of a developing human embryo. As proof of our aquatic past, these tiny muscles were developed in creatures that existed long before mammals appeared millions of years ago. I’m certain that our psyche is built up similarly, with traces of earlier generations emerging and disappearing in our consciousness. So, we are parts of a chain that developed before us and will continue developing after we are gone.

While photographing a series of mineral formations in 2010, I remember wondering how to categorize things as living or non-living. If a stone grows, is it alive in ways we can’t understand or measure? Native Americans use the expression: liquid stone. It’s not a reference to molten lava but to the existence of a stone as a developing being in constant motion. Empathy and imagination are fantastic superpowers. We may envision the lifecycle of a stone if we stretch our imagination and empathy towards all things. It’s a profound vision and a vantage point that opens an entry to a larger and fuller world. The stone changes, the world changes, and we change, too, no matter how much we hope to remain eternal. It’s funny and vain and, unfortunately, also dangerous, this mortal fear of change and loss of control.

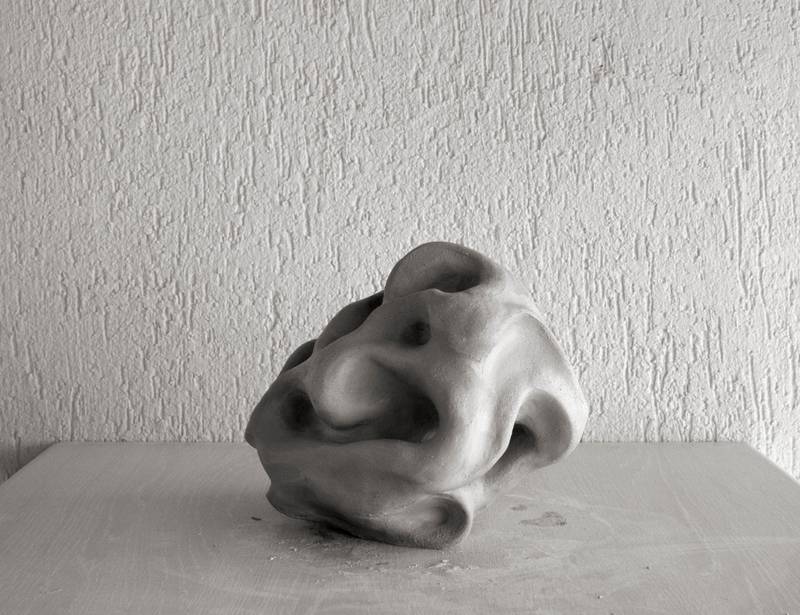

A Sleep that Navigates the Tides of Time, 2023, bronze sculptures and belemnite fossils | Photo: Jussi Tiainen

This ethical responsibility to accept our human temporality, yet to be deeply interdependent with everything, is truly urgent. A focus on deep time or more-than-human modes of existence can, at times, make us lose sight of our accountability. Do you find this a challenge? How do we weave these interdependencies into view?

Yes, it’s important to acknowledge that culture grows out of nature, as it tells us where we come from and how this interlinked relationship came to be. This long and evolving relationship also requires that we recognize our responsibility as humans.

This might sound as if I’m contradicting myself, but I think we can’t afford to be lost in a fantasy of being something else than humans in possession of the power to destroy or sustain. To perform immersion in nature often feels like a superficial ritual, not born out of respect but motivated by something else. You see a tendency in art where these approaches are used perhaps too lightly. To be consumed by and absorbed into nature is something we can only achieve by dying and decomposing. This is why I also find the claims of artistic “collaborations” with nature problematic since we can’t ask for permission from nature to participate in our works.

I read a 1957 essay titled East and West by philosopher D.T. Suzuki, comparing the Eastern approach to nature with the Western one, using a poem by the Japanese haiku poet Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694) and an equivalent poem by the English poet Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), to illustrate his point. In their respective poems, both notice and describe a humble flower growing on the roadside. Tennyson picks it up, roots and all, yearning to understand its inner workings fully. Bashō does not pluck it. He looks at it, nearly wordless. By seeing it as it is, being aware of a flower full of its flowerness, its true self, comes much closer to the flower than by any other means possible. With this contrasting way of thought and observing also comes the realization that we inhabit the same planet but two very different realities and that reality encompasses much more than we think. To analyze and dissect, or to be aware of each other as separate but equal beings consisting of the same fiber that the universe is made of.

To perform immersion in nature often feels like a superficial ritual, not born out of respect but motivated by something else. You see a tendency in art where these approaches are used perhaps too lightly. To be consumed by and absorbed into nature is something we can only achieve by dying and decomposing. This is why I also find the claims of artistic “collaborations” with nature problematic since we can’t ask for permission from nature to participate in our works.

In your previous work, you have also been thinking about the significations and symbolism connected to the female body. I found these questions were present, albeit implicitly, also in this exhibition.

In my earlier work, I have been drawn to organic materials, such as milk, blood and hair, often specifically exploring the symbols and attributes connected to the female body and the disturbing fact that the body, and especially the female sex and gender, is in several cultures considered impure. This exploration led to different outcomes: for instance, the photographic series Limbus was documentation of still-lifes consisting of flowers, hair and fruit left in the forest to decay and then photographed at night a few months later. They reminded me of ritualistic burial sites or forensic photographs of something forbidden, seductive and repulsive. Surprisingly, they also became observations of how inevitably and gently nature claims things back, as the installations were now homes to snails, ants, fungi, mould, worms and spiders.

The exhibition at Taidehalli took another path. For example, as I was sculpting the forms that eventually became bronze sculptures in the work A sleep that navigates the tides of time (a quote from Dylan Thomas), something happened. As I worked with the clay, shapes appeared and out of this process came forms reminiscent of fossilized sea creatures or insect pupae but also vulvas and ancient fertility statues of Venus. They were zoomorphic figures, familiar and alien at the same time.

To return to the polished cliffs in the outer archipelago, their strong bodily presence called to mind a protective womb, a place where new births and transitions could happen. I miss seeing the sun’s light caressing the surface of the rock, the cold stone collecting the warmth, and sensing the presence of some kind of cosmic love. This was comforting as I recognized a sorrow and an elusive void in me and around me. Maybe it was a longing for the lost maternal gods that dwelt in the land, received the dead and made the crops grow. So, I guess I’ve been moving from a politically defined body towards a healing body or a broken body to be healed.

Mutabor II, 2023, giclée print

Mythopoesis, 2023, 16mm film

You have previously described your need to grow roots, or mycelia, in places where you are working. I find that this goes somewhat against the grain of the accelerating circulation in society. What do returns to places allow for in your work?

I’m not super fond of traveling, so when I go to places, I’d rather stay as long as possible. It also allows for another kind of rhythm in the working process. You can wait, listen and look around. When you start developing those fragile roots, a part of you is left behind when you leave. Returns allow you to see changes differently – you are not the same as before, the trees have grown a bit or fallen, buildings have risen or disappeared, and the lines in the landscape have moved – but the pulse and the roots are still there. Sometimes, a certain place signals to you that this is where you belong. You could make this your home. I miss some places terribly. It might be a phantom limb aching, a yearning for a landscape we never had or that is lost.

We have worked together a few times, and in these collaborations, you have always made an intervention of some kind in the different contexts in question. But you have also shown your work in a wide range of exhibition venues. What is the significance of the institutional frameworks and physical spaces for your practice?

The context in which artists present their work is always important, as the creative process continues while you install your work in a new place. You might search for unconventional solutions in conventional spaces or the other way around. No matter which approach you choose, the work must be accessible; it needs to communicate. It’s great to see a resonance between the art and the room, whether it’s based on balance or disorder. Certain spaces resonate beautifully, no matter if they are galleries, museums, garages or toilets. I wish museums would consider making more satellite exhibitions or installations outside the white cube model. The Helsinki Biennial is a good example, and I hope that artists are granted more time to develop projects in such an exceptional environment as the island of Vallisaari.

The questions you explore about time also require resonant working processes. What has made these slowly evolving and long-term enquiries possible in your practice?

My artistic practice, in general, is dependent on grants. Many of my journeys abroad have been connected to residencies. In recent years, my work has been supported by one or two-year grants, which don’t really allow for a sense of security for the future or support concentrating on slowly developing projects. Still, these processes can’t be rushed. I’m using materials and mediums that are slow to work with. Working with film requires patience, especially when using a vintage Bolex camera. I love analogue film for its connection to history, its material presence and authenticity, and the almost alchemical qualities of creating an image on an emulsion consisting of light-sensitive silver crystals. Often, the filming is dependent on various weather conditions or seasons, and if you miss one spring, you need to wait for the next to continue. There is a meditative quality to working with materials that you can’t completely control.

Beacon, 8mm film, 2019, expanded cinema event

Take a stone in your hand, 2023, precast concrete ring, stones, text | Photo: Saara Ekström

Your point about working outside the white cube reminded me of how you have presented Beacon as an expanded cinema event, projecting the round moving images with small portable video projectors onto the viewer’s body or hands. Like the beacon of a lighthouse, the work draws into visibility and focuses attention on different details of the filmed island ecosystems. Moreover, perception shifts radically in terms of our sense of interconnectedness and responsibility when the work becomes something you, in a way, hold rather than view. Is this something you were also thinking of in Taidehalli with the stones for the viewers to hold in the exhibition?

Yes, it has always felt important to get close to the viewer to open up possibilities for communication while respecting people’s intimate spaces. At Taidehalli, I knew that there had to be a concrete, meditative and gentle way for the viewer to encounter time and find a connection to geological events. A stone, small enough to fit in your hand, was such a wonderfully simple and perfect tool for this. It’s both physical and metaphysical, expanding way beyond its size. My original idea at Taidehalli was that the stones, the co-travellers the audience held in their hands through the exhibition, could be carried away to continue their journey. A lot of stones did disappear despite the instructions to return them, which makes me happy!