Portrait of Artor Jesus Inkerö, photo by Silvia Martes

nadiye is a contemporary artist working primarily with sculpture and installation. their precarious practice engages with the body, the self, and the ways in which these are produced and constructed.

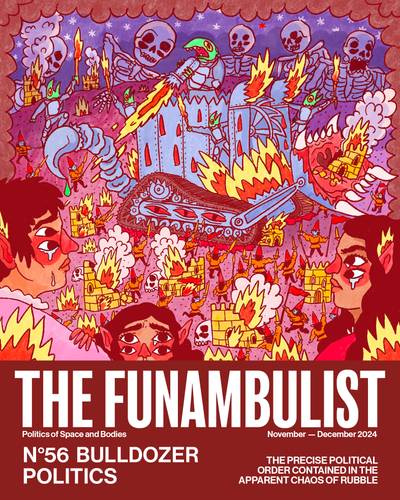

Artor Jesus Inkerö is a Finnish artist whose wide-ranging practice spans from video to performance, from ceramics to painting. Their work deals with queer identity and belonging. I met the artist at their (literally) cool studio on an overcast Sunday afternoon. We sat down by a radiator to discuss some themes around their work in the exhibition Home Is Where My Mouth Is in Helsinki Contemporary. Our discussion hovered around needs: for space, for privacy, to change, to move — to remain ambiguous.

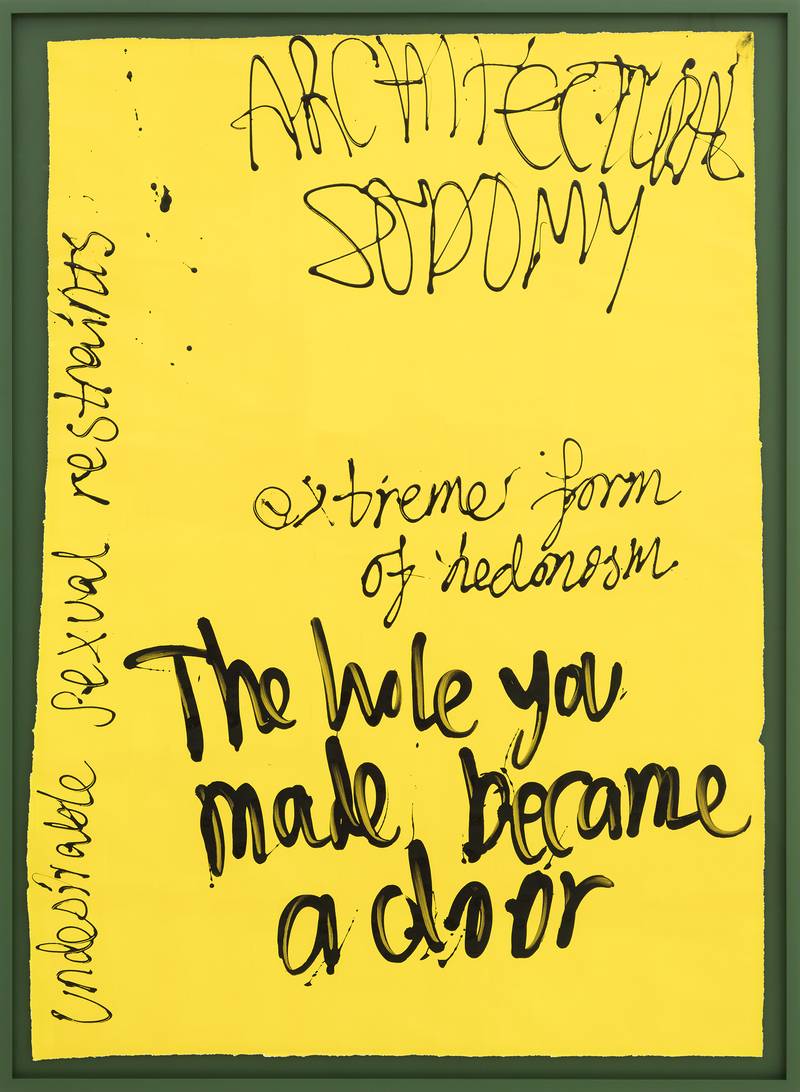

NADIYE: The exhibition text for Home Is Where My Mouth Is brings up the need for queer architecture. Can you go into a bit more detail on what you mean by the term?

ARTOR: I think it relates to the home. The home is a necessary structure, an actual, tangible structure that people live in — or don’t live in — that has a tremendous effect on how much influence a person or a community has. We, in a capitalist sense, have the freedom to choose where we live, but then we also don’t actually have those options. I think the illusion of freedom and perhaps of home itself is crumbling or has already crumbled.

In a poetic sense, I repeat certain spaces and their functions throughout the exhibition; windows, holes, drains and other things that connect to bodily experiences and also to various domestic acts and rituals, like taking a shower. Maybe these things function as an umbrella for people and life, which is what makes it queer, and not the architecture in itself.

You also mention queer architecture during your artist talk with Max Hannus.

In my conversation with Max, we talked about home decorating and interior design. There is a fascinating appropriating or capturing queer power to it. You can change any space according to your own interests and use it however you want. Gay men would historically cruise and have sex in parks, in the bushes, I wonder if that would make parks queer architecture? And is it then anti-queer architecture when those bushes are cut down?

Perhaps there is a queer potential coded in certain structures, the freedom of modifying them to suit your own purposes rather than the designer or the architect intended them to be used. Maybe you can find queerness anywhere.

That is an interesting thought. What kinds of structures are you referring to?

I don’t mean just the structures that we can see and directly experience in our day-to-day lives, but also the ones we don’t see. Why do we live in the kinds of apartments we live in, why are they priced a certain way, why do we vote a certain way? All these societal systems are in place that only allow for a very specific kind of Western lifestyle. But we can begin to capture things with different methods and tools within it.

Installation view of the exhibition ‘Home Is Where My Mouth Is’ at gallery Helsinki Contemporary, Artor Jesus Inkerö, Photo: Jussi Tiainen, 2024

Installation view of the exhibition ‘Home Is Where My Mouth Is’ at gallery Helsinki Contemporary, Artor Jesus Inkerö, Photo: Jussi Tiainen, 2024

My friend was telling me how a while ago they locked eyes with someone in public and then later connected on Grindr. It made me think about this online, gay subterranean network as a kind of architecture.

You could definitely think of various communal structures like that. Apps, discussion forums, why not even Spotify playlists! They connect people. Queer people have been especially good at building those connections and utilising the internet in furthering the political agenda. Even apps that weren’t really meant for it, such as Tumblr, somehow became queer things.

I don’t know if I agree with this, but I was discussing what queerness is and isn’t, and a friend of mine said that everything that is called queer is queer, because anything can be queer. You can find it anywhere.

I really struggle with that. Surely not everything can be queer! But then, when I try to argue against it, I’m not sure I can…

It is annoying! It is a little like how “everything is political”, of course, it is, but in what way is in my view the more pressing question.

If everything is political, and if everything is queer, then maybe we are asking the wrong question, and it is not that worthwhile to figure out what something is.

And isn’t this something that we keep saying, that we are tired of discussing these very rudimentary questions about what is and what isn’t queer? We can go back and forth, we can ask presidential candidates what they think, and we might get some answers, but those answers are really not all that intriguing to us. I think we already know what we are!

We increasingly communicate via text in a manner that feels closer to speaking — in text messages, posts and so on — which has made me think about the differences between writing and speech, also in the context of your paintings. Would you say your writing is closer to speech?

I’m not sure that my work is speech, necessarily, but something I realised recently with my poetic work is that it has a musical quality to it. During the production of my video piece, A Taste of Every Dish You’ve Eaten, we did not need to arrange my writing at all, because it was already so lyrical on its own. I think there is a kind of recital or song present in poeticism or lyricism, so in that sense, it is like sound produced from the mouth, even if it only happens in your mind.

How do you understand poeticism and lyricism?

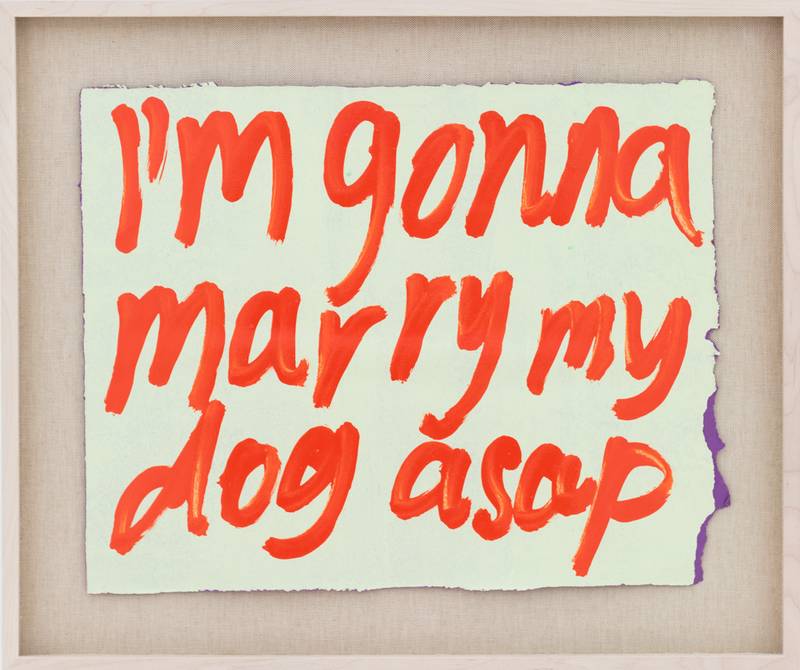

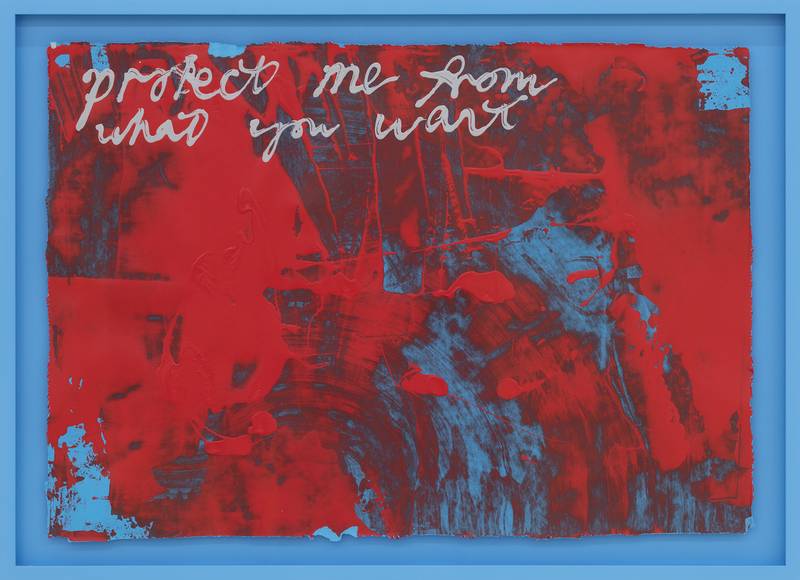

Maybe it is in the way you approach a text, as lyrics, as poetry, or something else. I see poetry as something that already exists in the language itself, it has something to do with how we conceive things. We are used to it in poems and song lyrics, but I want to ask if even something as simple as “I’m gay” could be open-ended in that same poetic way; to allow the reader or the viewer to understand things freely, in much the way poems do.

You brought up community earlier. How do you see community? Does it influence how you work, and how you collaborate?

To me, community means finding ways of living in some kinds of anti-capitalist, non-individualist arrangements. Collectivity and queerness are at their best when you don’t really have to think about them so much. I think we are accustomed to sticking out, so when you can communicate openly and honestly without constantly thinking about the situation, about being present or anything strange like that, without having to be so aware of your sticking out, maybe that is what it is.

I collaborate, almost without exception, with other queer people and allies — I mean actual allies, who truly strive towards accommodating us and understanding our needs — because it is much more pleasant. I have had a few difficult experiences during residencies and, for instance, with a producer who would consistently misgender my choreographer. If we constantly have to deal with very fundamental issues in production, how can we think about our artistic ambitions? Where can we move from there? It just does not work.

I’m gonna marry my dog as soon as possible, Artor Jesus Inkerö, Photo: Jussi Tiainen, 2024

Protect me from what you want, Artor Jesus Inkerö, Photo: Jussi Tiainen, 2024

You spent some time going through queer-historical material in queer archives during your residency at Somerset House Studios in London. Do you think about yourself and your work in the context of queer history?

While going through the archives I would make notes on little pieces of coloured paper to structure my thoughts, which is what eventually led me to produce the work in this exhibition. I think because of how tied to the archives and my stays there the work is aesthetically, that time, history, and the archive itself are present in the text as well.

I think about the kind of canon I create work to, the dialogues my work is related to. I hope that my work pushes the queer agenda forward in some way or brings something new to it. I want to make art for us, for the queer community, because it also allows me to examine myself more critically, without undermining our political struggles in the present. I believe that queer people change along with the changing vocabulary, and always have. I’m interested in how queer people have been verbalised and spoken about, and in the direction in which we are heading.

What direction do you see us heading?

I have noticed, in my own circle of friends, that words such as gay and lesbian have gained a more humorous tone, which seems to me like a sign of their falling out of use. Perhaps people don’t feel as attached to the categories or themselves. I am seeing more and more people just say “I am queer” and leave it at that, and I think it is wonderful.

We are constantly changing, which is why many people think we don’t mature. As if we were timeless. I think we as queer people ought to be more aware of our past and present. What does it mean for us to be here, now? What are we permitted to be? And what were we not permitted to be 50 years ago, or less than a year ago?

What would you say we are permitted to be? Or not permitted to be?

So much has happened within how we view queerness in a few years that it is difficult to keep up. Things haven’t had the time to become established. We have had periods of hypercategorisation which has increased diversity, but it has also pressured people to reveal more and more about their queerness to the public. I think of it as a private matter. It is a little strange to view people through how they have sex. Why do we need to be introduced, in public or in private, through our gender or our sexuality? Why are we not allowed privacy? Can we only gain justice by giving up the privacy that is afforded to the general public? I think the preference for ‘queer’ is very much of this time, it covers everything without divulging too much, without boiling gender or sexuality to any one thing.

Because queer identity does not align with society, it is an exception in the system, can it really have a planned, safe future at all? I don’t know how queer people age for example. Is that because we aren’t really given a chance to develop? The desire for queerness to remain a simple and easily understandable category — it locks queerness into place, and I don’t think it is stable at all.

Architectural Sodomy, Artor Jesus Inkerö, Photo: Jussi Tiainen, 2024

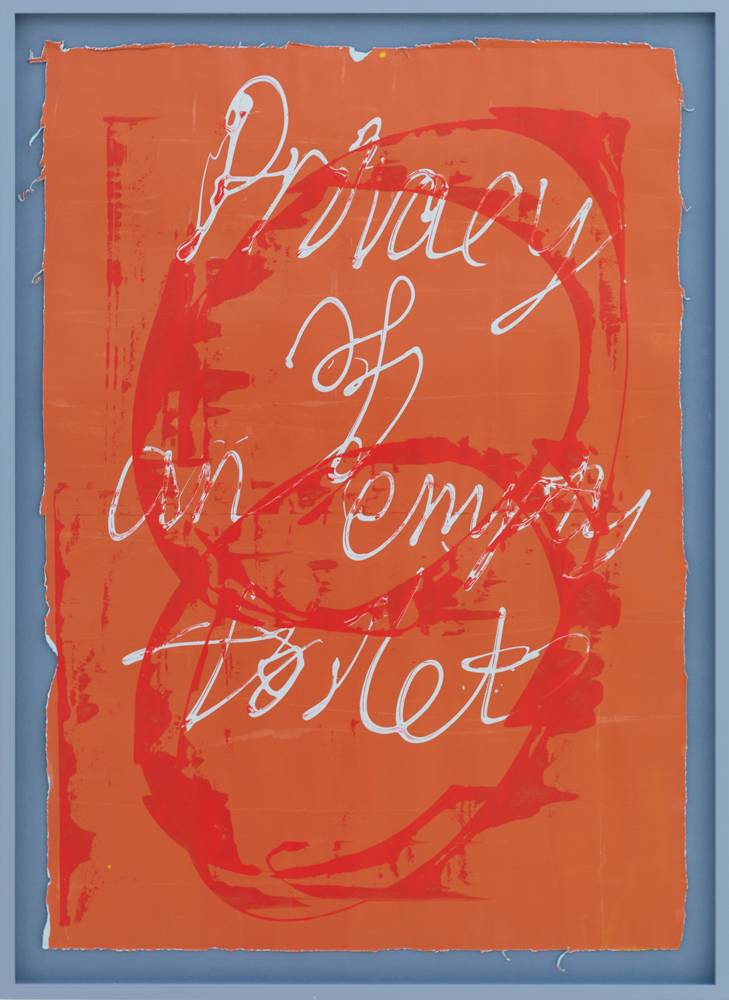

Privacy of an empty toilet, Artor Jesus Inkerö, Photo: Jussi Tiainen, 2024