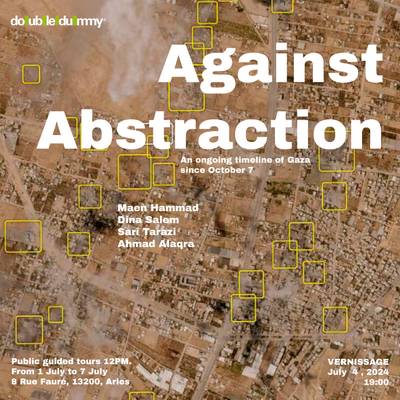

Ryoji Ikeda, data-verse 2, 2019

Ali Akbar Mehta (b. 1983, IN/FI) is a Transmedia artist, curator, researcher and writer. Through a research-based practice, he creates immersive cyber archives that map narratives of history, memory, and identity through a multifocal lens of violence, conflict, and trauma.

‘Ryoji Ikeda’, on view at the Amos Rex Museum from September 27, 2023, to February 25, 2024, is the eponymous artist’s first solo exhibition in Finland. Curated by Terhi Tuomi, the exhibition contains five works spread over three exhibition spaces. The exhibition design is simple yet arguably effective. Amos Rex’s architecture and darkened spaces lend themselves magnificently to creating the mystique and aura of the exhibition, creating moments of shock and awe as you pass from darkened corridors to dark rooms holding spectacularly massive projections of light and sound. This becomes evident as you enter the first exhibition room that holds ‘mass’ and ‘spin’, two new site-sensitive works inspired by Amos Rex’s observatory-like architecture, developed by Ikeda specifically for the exhibition.

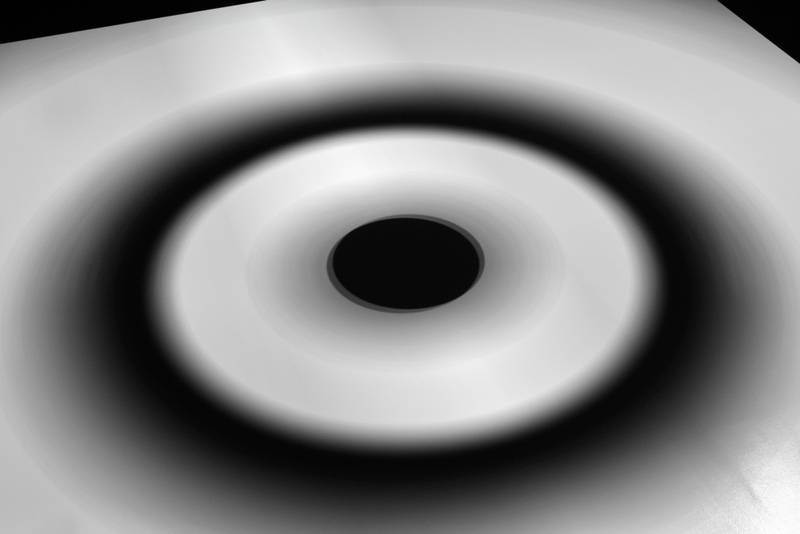

Mass is a space-dominating audiovisual installation “based on the polarity of oscillating whiteness and slow movement of black entities that hover amid the pulsating light”1. Any text on Ikeda’s decades-long practice will talk about his extensive yet minimal use of black and white as signifiers of presence and absence, or of physics and data, wave motion and sound frequency. While any of these may all be valid, I, on the other hand, want to convey the strikingly visceral presence of sound that physically crashes over you in waves as you enter the room. Not a loud sound, but heavy, almost tangible in its weight and intensity as it throbs in controlled, deliberate, rhythmic booms. A sound that vibrates through your entire being, washes over you and commands you to follow in its wake, inviting you to become synchronised satellites, moving in slow, concerted rhythms. The work is spatially aggressive, as it fills the room beyond its dimensions.

Ryoji Ikeda, mass, 2023

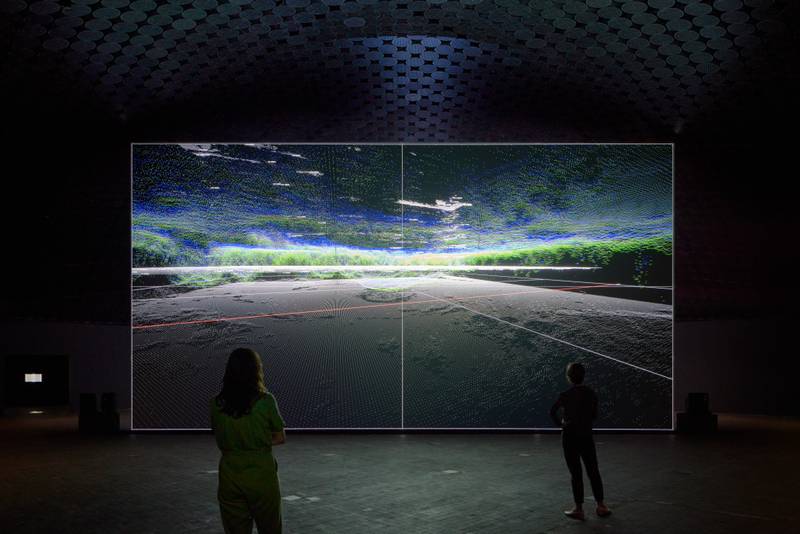

Spin, on the other hand, is light, both figuratively and literally. An effect created by using a monochromatic single-wave laser projection, rapidly oscillating to create a virtual orbit around an imaginary (planetary) body, it is discreetly tucked away in the characteristic skylight of Amos Rex, almost missable (and I did miss it, only finding its location on the map provided within the museum’s exhibition guide). Repeatedly inscribing itself in the darkness, Spin is a testament to the viewers’ persistence of vision. It is, in fact, a series of multiple dots formed by the laser, but to our eyes, it presents itself as a continuous Möbius Loop, without beginning, direction or end, forever spinning inside out, forever becoming and unbecoming at the same time.

Ryoji Ikeda, spin, 2023

The lightness of Spin is heavily pronounced, especially juxtaposed against the massively heavy presence of Mass. Spin is as ‘virtual’ as Mass is ‘real’. Yet both are manifestations of a struggle between light and dark to establish dominance over each other in some kind of abstract conflict. Forever locked in a temporal loop, negated by the actions of the other. Not by coincidence, perhaps, these two works introduce the uninitiated into the world and the aesthetics of Ikeda’s practice: Minimal, almost intimate in its aesthetics, yet immersive and all-consuming in its effect, data-driven yet poetic in its philosophical implications.

The sonification and visualisation of data are the thoroughline of Ikeda’s research-oriented work. He uses pure sine tones as well as white noise and organises his raw sounds to create rhythmic textures that are often danceable. His signature visual style consists of alternating black and white rectangles that create a sort of flashing barcode.

Often set to audiovisual rhythms and dramatic arcs, a significant influence by modes of scientific research, and mathematical precision. Ikeda’s long-term projects have taken a multiplicity of forms, from live performances and immersive audio-visual installations to books, records and CDs, and have evolved over the years to encompass the latest iterations of his data-driven research. His work has transformed the way we experience art and pioneered a global movement with immersive works that push our senses to new sonic and visual extremes, challenging our understanding of the universe and our place within it.

Ryoji Ikeda (b. 1966) is a Japanese composer, artist and data scientist, currently living in Paris and Kyoto. His artistic practice began in the 1980s and 1990s when he worked as a DJ, sound technician and composer. In the early 2000s, Ikeda expanded his artistic expression to include visual art.

My own introduction to Ikeda’s work was through his sound works, found in ‘albums’ such as +/- (1996), matrix (2000), dataplex (2005), test pattern (2008) and Supercodex (2013). Supercodex represented, as I learned back in 2013, the height of his practice with Glitch, a genre of electronic music that Ikeda pioneered as it emerged in the 90s in Japan and Germany, which is “distinguished by the deliberate use of glitch-based audio media and other sonic artefacts” (Cascone: 2000)2 In Computer Music Journal, composer and writer Kim Cascone classified glitch as a subgenre of electronica and used the term post-digital to describe the glitch aesthetic.

“The glitch genre arrived on the back of the electronica movement, an umbrella term for alternative, largely dance-based electronic music (including house, techno, electro, drum ‘n’ bass, and ambient)… released on labels peripherally associated with the dance music market and is, therefore, removed from the contexts of academic consideration and acceptability that it might otherwise earn.” (Cascone: 2004)3

The glitching sounds featured in glitch tracks usually come from audio recording devices or digital electronics malfunctions, such as CD skipping, electric hum, digital or analogue distortion, circuit bending, bit-rate reduction, hardware noise, software bugs, computer crashes, vinyl record hiss or scratches, and system errors. Sometimes devices that were already broken are used, and sometimes devices are broken expressly for this purpose.

“Ryoji Ikeda was one of the first artists other than Mika Vainio to gain exposure for his stark, bleepy soundscapes. In contrast to Vainio, Ikeda brought a serene quality of spirituality to glitch music. His first CD, entitled +/–, was one of the first glitch releases to break new ground in the delicate use of high frequencies and short sounds that stab at listeners’ ears, often leaving the audience with a feeling of tinnitus.” (Cox & Warner: 2004) Since the early 2000s, Ikeda has been working with scientific data, employing creative coding to develop an audiovisual language to explore what he terms ‘an aesthetics of data, information and computer science’. Ikeda’s studied meditations of ‘minimalist repetition’, exemplified in installations such as Test Pattern [100m version] at the Ruhrtriennale (2013) and Test Pattern [Times Square] (2014), became a characteristic and idiosyncratic means of slowing down data flow and focusing the listener’s attention on the nature and quality of sound and signal.

In 2013, Ikeda was accepted into a residency at CERN, the European Research Center for Particle Physics. Here, Ikeda’s practice began gathering an eclectic mix of myriad concepts, including quantum and particle physics and astro-cosmology. While the meditative serenity of his work remained intact, his massive installations shifted to engaging with data related to particle physics. The works produced as a culmination of this collaboration with physicists and engineers were Supersymmetry (2013-), co-produced by the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) and le lieu unique (Nantes), and ‘micro | macro’ (2015-) produced by the ZKM, Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. In the former immersive experience, Ikeda explores ‘The Standard Model’ of physics and the proposed theories of supersymmetry that help explain why (subatomic) particles have mass, while the latter refers to the ‘Planck Scale’, the universe’s minimum limit beyond which the laws of physics break. These two interrelated audiovisual projects simultaneously test the limits of what is knowable to us while slipping into realms of the unknown (even in Ikeda’s own evolving practice) and represent ongoing forerunners to his subsequent practice.

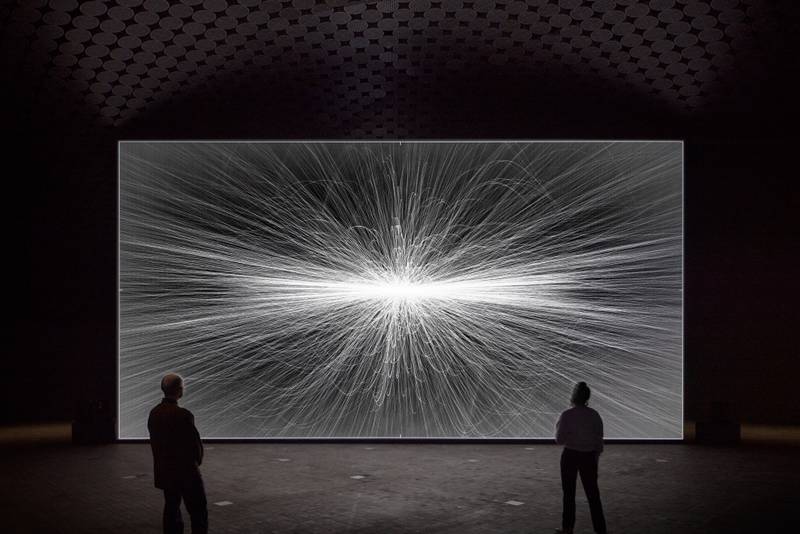

The second act begins as one makes way into the main domed exhibition room via a dark vestibule to the advertised pièce de résistance of the exhibition, Dataverse I & II (2019). Dataverse-I premiered at the Venice Biennale 2019, displayed in the main exhibition at Arsenal, curated by Ralph Rugoff. In this exhibition, a spectacularly gigantic freestanding monolith, 14 metres wide and almost 8 metres high, cuts the room diagonally at a precise 45° angle as a double-sided projection.

Known for being elusive, Ikeda has been an artist who prefers to show his work rather than talk about it. In a relatively rare interview about his ‘micro | macro’ series, he said, “Trying to map the whole universe is a crazy idea, but if you even slightly feel the vastness of this universe, everything, you will feel kind of awed, sublime, awe-inspiring.”

It may be almost impossible for most to not step back with a slight under-the-breath ‘whoa’ as Dataverse-I confronts us with its towering and authoritative presence, dwarfing the viewers not only through the size of the projection screen but through the massive amount of data that at first seems incomprehensible in its sheer volume: a rapidly shifting montage interweaving sparse acoustic compositions with a flood of visuals and vast fields of digitally rendered information. While the exhibition text informs us that “part of the works… is based on data from the massive archives of NASA, the Human Genome Project, and CERN, among others” the true scale of this impressive montage and the breadth of human experience it encapsulates only become clear as one spends time with the work, often requiring multiple viewings.

Slowly, a list of what one is faced with begins to emerge: The Dataverse-I is a montage of data concerning neural nets, DNA maps, genome and genetic data, microchip layouts, maps, computer chipboard designs, brain scans, computer-generated maps, bone scans, human and non-human body scans and drawings and visualisations, stock market graphs, currency valuation graphs, aerial maps of cities (photographic and drawn), infrastructures, public work development maps, data networks, other networks, planetary systems, global traffic visualisations, global economic market and transaction traffic, air traffic visualisations, deep sea scans and oceanographic data, sonar data, radar data, terrain mapping visualisations, photogrammetry data, celestial body data, crater depth and volume of the moon, solar flares, and star charts.

By dismantling and re-structuring the working logic of Dataverse I, Ikeda is not simply creating multiple versions or even revisioning his work, but instead I propose that version 2.0 implies versions 3.0, 4.0, and so on, signalling the opening for a ‘participatory culture’, a ‘remix culture’, where the final work, as a video, or an object in the museum space, is no longer sacred, sacrosanct or irreproducible, but instead is only a faux representative front of the true work—work that is being done in the processual sphere.

Ryoji Ikeda, data-verse 1, 2019

These, forming a list that is in no way comprehensive, integrate to form the artist’s own expansive language, a language that relies on an algorithmic way of working where mathematics is utilised as a means to capture and reflect the natural world around us. About the Dataverse series, Ikeda says, “It’s a bit like the film Powers of Ten by Charles and Ray Eames, but the scope is much, much wider. In 11 minutes, you go on a journey from the micro-scale to the scale of the universe. Usually, I visualise scientific data relating to very small or very big things. But here, for the first time, I included some data related to the human scale, ranging from proteins to anatomical parts to cities.”

The second iteration, namely Dataverse-II, is the same visual material set to the common soundscape, albeit differently ordered. This re-edit, re-sequencing, re-mix, re-make, and re-hash is intended to signify different, new meanings. By dismantling and re-structuring the working logic of Dataverse-I, Ikeda is not simply creating multiple versions or even revisioning his work, but instead I propose that version 2.0 implies versions 3.0, 4.0, and so on, signalling the opening for a ‘participatory culture’, a ‘remix culture’, where the final work, as a video, or an object in the museum space, is no longer sacred, sacrosanct or irreproducible, but instead is only a faux representative front of the true work—work that is being done in the processual sphere.

These ideas finds an extension in the adjoining room, containing nine thematic perspectives from the large data.gram series that are exhibited together for the first time in data.gram [n°5] (2023). The work reminds us of the multi-modal, simultaneous, yet fragmented structure of the data that we constantly encounter in today’s information society. Collectively, the Dataverse and data.gram series represents not simply an invitation to participate in the collective knowledge production apparatus but also highlights the developed evolution of a ‘transmedia culture’ within contemporary art practices, especially within the domains of generative data-centric new media art.

According to author Henry Jenkins, although Transmedia may translate as across media, it can simply be understood as narratology that “unfolds across multiple media platforms, with each new text making a distinctive and valuable contribution to the whole. In the ideal form of transmedia storytelling, each medium does what it does best […]” (2006)4 A transmedia mode of working implies moving beyond multimedia—the use of multiple media within one’s practice, where the use of those media may be disjointed and fragmented within the practice. While Transmedia also uses multiple media, it is marked by a convergence, where different media create a unified and coordinated experience of a single narrative. Ideally, each medium makes its own unique contribution to the unfolding of the narrative (Jenkins: 2007).5

Transmedia as a term encompasses two distinct meanings; rather, its usage is in two specific directions. One is that content is transferable or compatible across various technological platforms for its distribution. This digital interconnectivity has already become the norm for cross-platform migration of information and relies on the ever-increasing evolution of technology as a guiding parameter for increasing interconnectivity and how information is consumed. The second meaning of transmedia that a content creator, knowledge producer, (or in this case, the artist) understands is the ability and proliferation of the world of the story to be told in the various media and technological platforms available—to uniquely express or utilise the specific technique and technological availability in different media.

Transmedia narration is the ideal aesthetic form for an era of collective intelligence. Pierre Levy coined the term ‘collective intelligence’ to refer to new social structures that enable the production and circulation of knowledge within a networked society. Participants pool information and tap each other’s expertise as they work together. Levy argues that art in an age of collective intelligence functions as a cultural attractor, drawing together like-minded individuals to form new knowledge communities. Transmedia narratives also function as textual activators – ‘setting into motion the production, assessment, and archiving [of] information. In the process of archiving information, we create knowledge archives’ (Jenkins: 2007).6

What is significant in Ikeda’s Dataverse is that ‘the like minded-individuals’ is not restricted to the artist, that the probable ‘we’ in Jenkins’ statement is you or I. This reality is especially laid bare with the understanding that while the datafied visuals may be generated by the artist (and the artist’s use of proprietary software), the conceptual significance inviting a collective participation is the fact that the data itself is not. It is, relatively speaking, publicly accessible and part of a digital commons, awaiting potential intervention.

![Ryoji Ikeda, data.gram [n°5], 2023](/images/wpos68fwrkeqy19bcxai-800w.jpeg)

![Ryoji Ikeda, data.gram [n°5], 2023](/images/wpos68fwrkeqy19bcxai-lqip.webp)

Ryoji Ikeda, data.gram [n°5], 2023

For anyone unfamiliar with The Tree of Life (2011), a film by director Terrance Malik, it is simply put, the story of a young boy and his undulating relationship with his family, particularly his father, told in 3 disjointed narrative streams. While the film’s predominant narrative takes place in 50s Americana, a second narrative with few flashforwards to the assumed ‘present’ of the boy as a man with childhood musings on his birthday, it is the third narrative sequence that I would like to divert your attention to.

This, the third narrative sequence, is an allegorical journey of many beginnings, from the prevenient cosmic nothingness to the Big Bang and the birthing of stars, galaxies, and superclusters. A story of the shaping of planets, the formation of mountains and oceans on Earth, and the primordial evolution of life from single-celled beings to plants and animals. Of change, from amoeba to invertebrate to aquarian life. Of the first creatures to transition to land. Of dinosaurs as complex land giants. Of death, singular as one dinosaur kills another; and cosmic, as a hurtling meteor shattered itself within Earth, destroying most life. An end. This montage, disjointedly spread across the ‘main’ narrative of the film, tells a story, a parallel juxtaposing the grandeur of macro narratives that set to scale the intimacy and tenderness of the story of a family of five individuals.

I am reminded of this montage when seeing Ryoji Ikeda’s Dataverse series. Except that now, the audio-visual sequence doesn’t simply tell a preformatted and scripted story. What the Dataverse series does is something more powerful. What it does is unlock the potential of a series of visual signifiers to mean more than what they are pre-designed and pre-designated to mean.

Perhaps Ikeda’s Dataverse may be viewed as an attempted return to a rhizomatic mode of narratology, where each visual does not necessarily lead to a successive logical linear narrative, but instead each visual represents its own affective, self-sustained dataverse, replete with its own meaning, logic and aesthetic. Perhaps Ikeda himself is not so concerned with the narrative, but the process, where multiple iterations as Dataverse I, II, and III provide the entrypoint into multiple, playful, constant potentialities of remixing and transmediatic enquiry.

Ryoji Ikeda, data-verse 2, 2019

The first striking feature of the Dataverse is how this vast amount of audio, visual, and simulated material is foregrounded—away from the realm of its usage as obscure background information, in front of which other more immediate narratives generally occur (in traditional or mainstream media). It is striking how Ikeda’s visual material shares a striking affinity with the ‘cutaways’ and ‘B-roll footage’ of cinematic vocabulary. This affinity is so overwhelming that to a seasoned viewer of cinema, such material may immediately seem mundane, and they may even be prone to being unmoved by the rapid montage of seemingly supplemental footage in Ikeda’s Dataverse. Yet, what is significant in this shift is the re-valuation of the otherwise insignificant, the everyday, and the infraordinary. The ‘Soviet Montage’ exemplified in the film Battleship Potemkin was Sergei Eisenstien’s contribution to the semiotics of cinema. As a theorist, Eisenstein believed that ‘cinematic language’ could be as effective as verbal language in producing concepts and ideas. Thus, the use of ‘intellectual montage’ contributes to creating an intellectual meaning through the juxtaposition of two shots or more, which collide to produce another that ‘becomes purely conceptual’. In Dataverse, this juxtaposition of out-of-sync time creates a conceptually driven framework that is open to interpretive re-readings and the imagining of speculative futures.

The second, even more consequential feature of Dataverse is that it represents a notable departure from traditional forms of storytelling. To elaborate this further, a slight detour: In the history of human and even pre-human, other-than-human communication, there may be very little that lies outside the realm of the narrative. ‘Linear’, ‘non-linear’, ‘multi-linear’, ‘parallel’, ‘disjointed’, ‘fragmented’ and ‘broken’ are all forms of time, but also narrative structures that we have witnessed across the breadth and depth of literature, sound, cinema, and multiple forms of art. To the extent that it would not be any stretch of the imagination to say that we humans are limited by the temporal idea, of a narrative unfolding in time, as the only possible form and technology of communication that we possess. All forms of communication structure conceivable to us boils down to the narrative, a story with clear beginning-middle-end syntax; and that narratology is at the heart of all modes of communication language since the known histories of human experiences.

Umberto Eco claims that there are three kinds of Labyrinths: The Linear, The Maze, and the Net (or Rhizome). For Umberto Eco, the Internet’s ‘every point can be connected to every other’ and therefore very much represents a ‘rhizomatic labyrinth’, branching out in multiple directions. It is important to note that during the Renaissance period, the concept of the Labyrinth was reduced to refer primarily to the linear, a paradigm that we recognise today. Espen J. Aarseth tells us that the old metaphors of ‘text as labyrinth’ could mean ‘a spatial artistically complex artefact was reduced to the meaning of being a difficult, winding, but potentially rewarding linear process.’ Subsequently, a form of narratology became popular where ‘Everything was required to make sense in the end (Aarseth: 1997). Again, one may refer to McLuhan’s studies that describe how the advent and normalisation of the written word led to the meteoric rise of linearity (McLuhan: 1971). As the writing came to signify the permanence of knowledge and rationalism, the rhizomatic ways of oral and aural transmission of knowledge became ‘hear-say’, the root term for hearsay and heresy.

Perhaps Ikeda’s Dataverse may be viewed as an attempted return to a rhizomatic mode of narratology, where each visual does not necessarily lead to a successive logical linear narrative, but instead each visual represents its own affective, self-sustained dataverse, replete with its own meaning, logic and aesthetic. Perhaps Ikeda himself is not so concerned with the narrative, but the process, where multiple iterations as Dataverse I, II, and III provide the entrypoint into multiple, playful, constant potentialities of remixing and transmediatic enquiry.

To approach this idea from another angle, I forward a proposition by new media artist and theorist Lev Manovich, that the hegemony of narrative time would have been true only until the invention and advent of the ‘database’. The database exemplifies the idea of a truly abstract, almost alien (to all other forms of communication and media) (data)space without a beginning, middle, or end.

In ‘The Database Logic’ Lev Manovich defines the database as a ‘structured collection of data’. (Today, databases do not require to be structured for them to be called a database – unstructured data clusters are also databases). For him, the database is the key component of new media that displaces the cultural hierarchy of the narrative form found in the novel and subsequently in cinema (or in any sequence or sequential form of artwork). Data, or clusters of data, defined as ‘objects’, do not in themselves tell a story; they do not have beginnings or end(ings); in fact, they do not have any development, thematically, formally, or otherwise, that would organise their elements into a sequence. A Database is a collection of individual items, with every item possessing the same significance as any other.

For Torsten Meyer, the database is amorphous, having no particular form but like water, mouldable to all types of forms. That’s why the database in itself, meaning data without a concrete detailed query, can’t be a real story, a narration or a history. It is in fact, a fundamental character of the database to not be a story.

“A database has no beginning and no ending. It has no theme, no ‘story’, let alone a ‘moral’, no order – neither a defined series of data presentable etc. Everything inherent to a story – as a narration or history – is missing. Anything that could be defined as the work of an author is missing. The author as someone who reduced complexity is absent. And therefore the standpoint of the author is missing as well. That’s why the principle of the linear perspective – as an agreement on a common standpoint of both painter and observer or author and reader – fails. (Meyer: 2017)7

Following art historian Ervan Panofsky’s analysis of linear perspective as a ‘symbolic form’ of the modern age, Manovich coerces us to even call database as the symbolic form of the computer age, or as philosopher Jean-François Lyotard in his famous book The Postmodern Condition, called ‘computerised Society’ (1979).

Ryoji Ikeda, data-verse 1, 2019

Ikeda’s Dataverse is a manifestation of precisely this symbolic form eternal, where each scene, each sequence, and each shot is the ‘data’ of what it depicts, simultaneously located in time and outside of it. As one spends time with these seamlessly looping videos, one cannot help but be reminded of Macluhan’s famous words, “The wheel is an extension of the foot … the hard disk is an extension of the brain” (Mcluhan: 1971)8. The database today is the extension of human (and non-human) knowledge and memory.

To me, Ikeda’s work represents a historic precipice, a zone beyond which artistic practice becomes increasingly processual and concentrated on its world-building, entangled within its own encoded data logic. Beyond this, any mode of output as exhibitable objects within exhibition spaces simply becomes representative of the work and not the work itself. The work then lies in the audience’s or participants’ willing entanglement within the intricate network of the artist’s densely populated research space.

While the material is complex, the experience of the exhibition is immediate, as the works are visually, sonically, and even physically striking. All five works in the exhibition are part of the artist’s broader exploration of the universe of data and the limits of perception. They demand undivided attention and offer new dimensions every time you experience it.