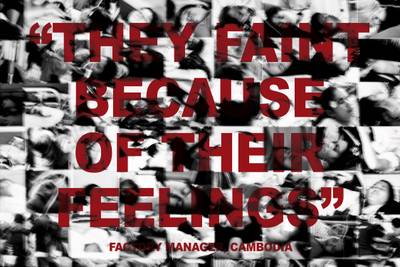

Baran Caginli, Expressions, 2021, Artsi Collection Exhibition, ‘My Home Somewhere’. Photo: Sonja Hyytiäinen

Varvara Kobyshcha is a PhD researcher in sociology at the University of Helsinki. She studies visual artists with migration and exile experience who relocated to Finland and Germany in the 2010s from the countries of West Asia/Middle East. Parallel to the dissertation, she is doing research concerned with the experience of cultural practitioners in (il)liberal political regimes, housing inequality, and critical memory studies. Her academic publications are available here.

“You must go on a long journey before you can really find out how wonderful home is.”

– Tove Jansson, Comet in Moominland

On January 12, 2024, the art scene of the greater Helsinki witnessed the opening of two simultaneous exhibitions exploring the themes of home and belonging. One, named ‘Feels Like Home,’ occupied two floors of the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma; the other, named ‘My Home Somewhere,’ fit into a much smaller space of the Vantaa Art Museum Artsi. These projects share more than just their themes and timing.

Both exhibitions had to be assembled from each museum’s collections. Artsi’s, however, has included the works of several artists who were invited to engage in a dialogue with the collection and works created within the research and art project “The Narratives of Finland: Historical Culture, the Arts and Changing Nationality.” Both target a general audience; hence, each visitor should be able to find at least one work to identify with and leave the museum with the satisfaction of feeling represented. Both highlight the same sub-topics: multiplicity of home as a physical, cognitive, and social category; a plurality of belongings; problematisation of home and belonging through migration, exile, and various forms of violence. Lastly, both exhibitions encourage their visitors to think about how they relate to all these categories. But to prevent the audience from getting carried away, both museums stress in their press releases how we should measure our home and belonging, both nationally and locally.1

Home and belonging (along with “journey,” “community,” “body,” “technology,” “connections,” “environment,” “crisis,” “memory,” “care,” etc.) are some of those vague keywords that have been reused in contemporary culture for various purposes time and again. They are broad enough to appeal to any person, be addressed in a universal or even existential way, and, at the same time, be easily related to whatever is happening in the news. They are useful when one needs to come up with a project title for a grant application or to fill out the programme of an institution. Given that they are used so frequently, is it still possible to do something new and impactful with those words? And, if that is possible, what are the conditions that would allow such categories to be revitalised through contemporary art and have an effect?

Handbook Approach

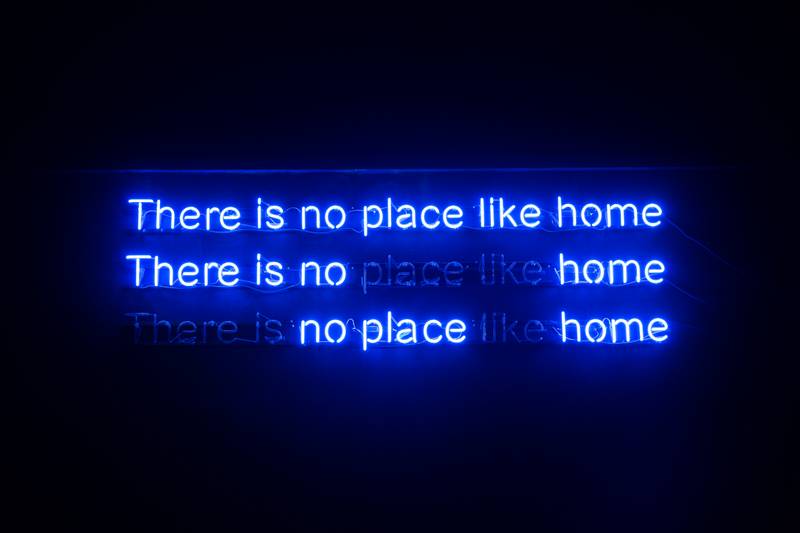

The curators (Pauliina Kähärä in Artsi, Saara Hacklin, Satu Oksanen, and Saara Karhunen in Kiasma) approached these exhibitions in a handbook manner: they identified various contexts in which home and belonging are most typically explored by means of contemporary art and compiled corresponding artworks in thematic chapters. Through such handbook exhibitions, their audiences should learn key ideas related to home and belonging and incorporate them into their perception. In Artsi, each chapter (changing boundaries, family relations, domestic space and objects) is introduced by a rather didactic curatorial text. For instance, the first chapter uses a rhetorical question: “Can home ultimately be a feeling born within us, no matter where we are in the world?”. To answer the question, it provides the audience with a variety of artworks, including figurative and abstract paintings, objects and installations made from paper plates, lead and marble, neon lights, glass, metal, photographs, and clay. The themes of the artworks are as diverse as the materials they are made of. They encompass matters of colonisation of the Arctic region and Sami people, community-dwelling in the Finnish nature, “refugee crisis” in the Mediterranean region, life in the asylum centre in Vantaa, global travelling, Finns’ and Swedes’ migration to the United States, and even the growing distance between parents and their son, who is thinking about how to come out as an artist.

The structure of the Kiasma exhibition is more loose and less didactic, and nevertheless, the handbook approach is noticeable: the audience encounters an even larger kaleidoscope of different perspectives and media that artists chose to tackle various issues associated with home and belonging. The collection of the Finnish National Gallery, predictably, allows the curators at Kiasma to present a broader scope of media, concepts, and authors than the Vantaa Museum could afford. Apart from Finnish and foreign-born artists residing in Finland, ‘Feels Like Home’ shows works from several international artists: Berlinde de Bruyckere, Jannis Kounellis, Frida Orupabo, Farah Al Qasimi, Lesia Vasylchenko, and Anastasia Sosunova (whose works were present during the spring season). However, whenever there is a direct reference to a particular location or community, it is limited to the Baltic region or a journey towards it.

Farah Al Qasimi, A Reclining and Blue Gatorade, 2020 and 2021, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery Feels Like Home, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Kansallisgalleria / Pirje Mykkänen

Berlinde De Bruyckere, Anonymous, 1996, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery Feels Like Home, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Kansallisgalleria / Petri Virtanen

Jannis Kounellis, Anonymous, 1990, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery Feels Like Home, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Kansallisgalleria / Petri Virtanen.

Frida Orupabo, Two Sides to Every Coin, Mother and Child II and Untitled, 2021, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery Feels Like Home, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Kansallisgalleria / Pirje Mykkänen

Thanks to the common approach, similar aesthetics, and overlapping topics, both exhibitions could be easily and almost seamlessly sewn together, starting with the aquarelles of Marjatta Hanhijoki that are included in both shows. The ceramic objects of Sanna Murtti (2022) and Maria Stereo (2018) from Artsi could be combined with the Porcelain Tower (1993) by Henrietta Lehtonen. The photo prints (1989) by Jukka Lehtinen could be juxtaposed not only with the paintings (2022) by Mirza Cizmic that are inspired by amateur photography but also with the painting (2014) by Kaarlo Stauffer created in a similar technique.

Neutralisation, Reification, Fetishisation

The purpose of a handbook is to give a comprehensive overview and educate the audience about a certain subject, which both exhibitions successfully accomplish. However, a handbook does not tell a story and does not make a statement.

The curators’ distant and formal approach leads to the artworks being neutralised rather than re-enforced. The exhibits are assembled so that a visitor would notice similarities and differences between them, but there are barely any tensions, conflicts, or unpredictable cumulative effects. They simply coexist.

It is less problematic in the case of the small Vantaa Museum. The theme of the exhibition fits well with the museum’s local focus and the city’s anniversary programme. The darker and more compartmentalised space of the Artsi hall helps spectators focus. The clear thematic structure and didactic style of the curatorial text guide the audience through the show. If it goes as intended, visitors will learn some of the established and even mainstream ideas around the theme of home and belonging that have been circulating in contemporary art and the intellectual sphere more broadly. But the Kiasma exhibition functions a little differently. The audience’s focus gets more easily distracted as it faces a wider range of artworks that have a less clear connection to each other.

The curators’ distant and formal approach leads to the artworks being neutralised rather than re-enforced. The exhibits are assembled so that a visitor would notice similarities and differences between them, but there are barely any tensions, conflicts, or unpredictable cumulative effects. They simply coexist. When this subject is represented in a handbook manner, it creates the illusion that all these different belonging-s exist parallel to one another. There are no struggles, no hierarchies, no competition for space to make into a home, no exclusion, and no segregation. No matter how distinct sensations of home are, no matter how fluid and multiple belongings are being put together, they constitute a cohesive unity, whether it is an exhibition, the city of Vantaa, Finland, or any other so-called multicultural community. However, in reality, they do not just emerge from nowhere. And they do not co-exist in a flat, egalitarian way.

Let’s have a glimpse of the world outside the museum walls. To have a substantial chance for a temporary new home in Finland, at least within an asylum centre, one should better be recognised as a white person. The rest of the people, who are trying to escape wars, repressions, and economic and ecological disasters, are seen by the state and mainstream media as “instruments” used in “hybrid warfare” and as a threat to the Finnish Kotimaa [homeland]. No one would, for instance, put Iraqi or Syrian flags around the city or, as of now, even let asylum seekers from such countries close to the Finnish border. To continue belonging in Finland as a harmless “expat,” one needs not only to prove that they still have grounds for the residence and are financially sustainable, but they must also divulge, in writing, the exact dates, destinations, and purpose of every trip abroad that they made during the previous period of residing in Finland. If you were granted the right to stay, you should better belong here for good and not dare to belong somewhere else at the same time. To belong in Finland, one has to learn how to respond to blankly racist and/or ignorant statements in a nice and polite way so that the person who made such a statement would not feel offended. To belong in Finland, even a person born and raised here should avoid studying and being employed abroad for too long because they “forget” how to work “the Finnish way.”

“Home” and “belonging” are peaceful, positive keywords that can cover up issues related to much less pleasant things, such as nationalism, racism, exclusion, housing commodification, power and control.

To be fair, some of the art pieces included in the exhibition do tackle more problematic aspects of home and belonging. If visitors pay close attention, they will notice, for instance, how a female character from Jani Ruscica’s antiutopian video art Beginning an End (2009) watches TV news from the 2050s. The news shows Israel bombing the capitals of its neighbouring countries even in three decades from now. They will look closer at Jouni S. Laiti’s duodji items (2018-2019) and think about what it takes to acquire the status of the contemporary art objects in the collection of the National Gallery. They will concentrate on hearing how a Lithuanian craftsman in Anastasia Sosunova’s semi-documentary work Agents (2020) quietly and modestly dismantles the conservative but still dominant idea of national traditions. They will follow the teenagers from Anu Pennanen’s Friendship (2006) as those Estonian- and Russian-speaking boys and girls are desperately trying to entertain themselves by wandering around Tallinn, testing the social, spatial, and language boundaries of the early 2000s.

Anu Pennanen, Sõprus - Druzhba (Friendship), 2006, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery ‘Feels Like Home’, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Pelle Kalmo

However, when these and other artworks are assembled within a handbook-type project, their critical potential gets watered down. Both exhibitions’ curators highlight in their introductory texts how home and belonging are complicated concepts, especially when they are connected to the displacement of people due to political and social changes and disruptive historical events. However, the exhibitions do not go deep into specifying and analysing those circumstances. They also do not question what makes possible more familiar and cosy visions of home, as in the Homey painting (1978) by Kari Pärssinen or the portraits (1983-1988) by Marjatta Hanhijoki. Instead, they highlight the universal elements of home and belonging and focus on the formal connections between the selected artworks.

“Home” and “belonging” are peaceful, positive keywords that can cover up issues related to much less pleasant things, such as nationalism, racism, exclusion, housing commodification, power and control. When applied in a broad, all-inclusive manner, they tend to be subjected to reification in the Marxist sense: they are perceived as objective and “natural” attributes of particular people rather than a contingent result of changing social/economic/political relations. To put it simply, we are looking at how peculiar and diverse all those representations of home and belonging are, not sensing the gravity of relations behind them. In some cases, when it comes to the home and belonging of “refugees,” “diasporas,” or “indigenous” communities, it may reach the level of fetishisation.

Space and Intimacy

Home and belonging are, by definition, extremely intimate phenomena. When planning a conversation around these categories, one needs to carefully choose an appropriate scale and environment where such a conversation takes place. Otherwise, the audience may disengage from the conversation since it would not feel comfortable enough to dive into their own reflections on such personal matters.

At the same time, the categories of home and belonging are constantly circulating in public discourse, (trans-) national political agendas, and policies that states and civil actors adopt to manage culture, migration, urban life and other social issues. Consequently, these categories have become firmly embedded in bureaucratic languages and are often discussed in large formal settings. Thus, it is not surprising to see an exhibition devoted to home and belonging taking place at the spacious contemporary art museum, a part of the Finnish National Gallery. White walls, bright light, plenty of large-scale objects, and more cosy rooms on the second floor lead to much wider exhibition halls on the third floor of Kiasma. The exhibition architecture does not provide almost any chance for a more intimate, home-like feeling. It negatively affects some of the artworks, as, for example, Self-Portrait II (2014) by Sepideh Rahaa. The moment of balance and calmness that she created for herself and invited the audience to share deserves a separate, quiet space that could be carved within an exhibition hall. Instead, it is placed on a side wall, next to the entrance/exit of a room, and surrounded with other artworks that play with the ideas of in/outside-ness but seem too diverse to enhance each other. The only exceptional spaces that provide a more homey feeling are the dark rooms where video artworks are screened. This is where the audience encounters probably one of the most memorable and intimate works that the exhibition showcases – You cannot get what you want, but you can get me (2023) by Samira Elagoz and Z Walsh.

Sepideh Rahaa, Self portrait II, 2014, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery Feels Like Home, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Photo: Pirje Mykkänen.

Samira Elagoz & Z Walsh, You can’t get what you want but you can get me, 2023, Collection Exhibition of Finnish National Gallery ‘Feels Like Home’, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art.

The limited space of Artsi not only allows for visual conversation concerning home and belonging to be more focused and comprehensive but also creates a more intimate atmosphere compared to Kiasma. The local museum of Vantaa occupies a part of the second floor of the building that, apart from the museum, accommodates a cinema, library, information bureau for citizens, and a restaurant. This place, with free admission, functions as a rather accessible local community hub and links Vantaa to the cultural life of greater Helsinki. It feels informal and familiar, even if you do not live nearby and do not come here very often. All these elements make Artsi a comfy, human-scale place to engage in a conversation on home and belonging through contemporary art.

Moreover, ‘My Home Somewhere’ contains an object that allows visitors to experience home – with all its safety, fragility, and insecurity – in the most direct way. This object is the acoustic sculpture Home is not where I am (2020-2023) created by Ida Sofia Fleming. On the one hand, Flemings’ work looks alien to the rest of the exhibition. It is a relatively huge, 3-dimensional object that landed in the chamber museum hall. Thanks to the deep, repeating sound it makes, the audience encounters this object even before they enter the exhibition and realise where the sound comes from. Although it formally belongs to the “space and objects” chapter of the exhibition, it stands out against the background of paintings, photographs, and ceramic sculptures that showcase common material elements of ordinary domestic spaces. On the other hand, it is the most sensual and engaging of all the artworks displayed at the Artsi exhibition. I enter the artwork, move to the back wall and turn so that I can face the entrance covered with a piece of cloth. I touch the rusted metal walls; they vibrate with every soundwave that rolls into the building. I imagine myself hiding in this shed that has suddenly become a home for me. It must be one of a few withstanding structures left among the ruins I envision outside. The sound that I feel with my ears and my fingers reminds me of the military drones surveying the space above people’s heads.

Epilogue: Going Back and Elsewhere

To relive the feeling of home and belonging that art can give, I go back to late November 2022, when I came to ‘The Hanging Gardens of Oberlandstrasse’ Festival at the Atelier Gardens in Berlin. It was a contemporary art festival directed by Ayham Majid Agha. A few years before that, Ayham had been working with the Gorki Theatre and running the ‘Exile Ensemble’. This festival was a way to move from the lasting condition of exile towards the process of homing. The title of the festival referred to the legend that originated in Mesopotamia (contemporary Iraq and Syria): in the lowlands of Babylon, King Nebuchadnezzar II’s wife Amytis was longing for the forests and mountains of her homeland. The king tried to comfort his wife by creating the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The festival gathered Ayham’s friends and friends of their friends, among whom there were both Middle-Eastern, European, and Latin American artists. There were no “correct” proportions and no need to worry about representation. It was a naturally diverse community of people.

Although it was a quite substantial, complex, multilayered contemporary art festival, it felt easy and relaxed. We were invited to share funny, vulnerable, and intimate moments. We were not invited to be educated on the basic concepts that constitute a contemporary understanding of home and belonging.

The exhibition spread across several small rooms, an outside wagon showcasing individual projects, a detached basement with performances and installations, and a large hall where abstract paintings by Andrea Büttner were put into dialogue with the famous calligraphic works of Mouneer Al-Shaarani. Two weekends of the festival were filled with events: concerts, performances, discussions, workshops, eating, drinking, smoking, and talking outside in the breaks between the events. It was noticeable that, despite that a large share of the audience consisted of artists and their friends (which describes a majority of the Berlin population), there were plenty of “random” visitors: families, young professionals, elderly couples, and new refugees from Ukraine.

Although it was a quite substantial, complex, multilayered contemporary art festival, it felt easy and relaxed. We were invited to share funny, vulnerable, and intimate moments. We were not invited to be educated on the basic concepts that constitute a contemporary understanding of home and belonging. If the audience was completely immersed in drawing Arabic calligraphy and demanded more time before moving on to an artist talk, then so was it. If everyone’s favourite patriarch of Syrian art, Mouneer Al-Shaarani, needed a cigarette break before the talk, then everyone could wait, because this is how it goes when you are invited to people’s homes.

Probably the most important memory of my time at the Hanging Gardens is how safe and comfortable I felt participating in the festival events where, at first glance, I was not the target audience. One of them was the “Live Radio“ sound performance by Khaled Al Ismael. He assembled 10 minutes of street sounds, pop music, and radio broadcasts from the 10 years preceding the beginning of the Syrian Revolution. I was one of a couple of people in the audience who did not speak Arabic and could not grasp the exact meaning of the words in the sound stream. At the time, I did not have the experience of wandering through a Middle Eastern city and could not relocate myself to Damascus in my imagination, while almost all of the people around me could. However, through the similarities in the melodies of the 2000s pop music, through the recognisably concerned intonations of radio hosts, and through the laughter and comments of the people who were surrounding me in the basement of the Atelier Gardens, I felt welcomed at their home.

House of Cardamom, interactive podcast performance by Bolbola with Queen of Virginity, the Hanging Gardens of Oberlandstrasse Art Festival, 2022, Berlin. Photo by Varvara Kobyshcha

This sensation kept growing when I moved to the upper floor of the Atelier, following two drag artists, BolBola and Queen of Virginity. Their dressing room was turned into the performance space for the House of Cardamom. Everyone who could fit in found a space to sit on the small couch, a couple of chairs, and, mostly, the tiled floor. Bolbola and Queen of Virginity were leading the unscripted and unrecorded podcast-performance, gradually involving the rest of the people in the conversation. They were “gossiping” about homing, exile, returning to one’s childhood home, struggling with the normative idea of home as a permanent place, feeling (un)secure in queer spaces and much more. Bolbola was also constantly occupied with making, pouring, and handing to her guests coffee with cardamom, a typical drink that accompanies such daily gossiping rituals in Mediterranean and West Asian countries. The artists and the audience were joking, laughing, worrying about oversharing, and showing empathy. And the magic happened again. Ticking all the representation boxes does not automatically allow people to belong. Something else does. I am not a queer person, not an artist, not a person of colour, not in exile (as of now), and I do not have a West-Asian background. Nevertheless, I felt that I was recognised, that my concerns were addressed and that I belonged.