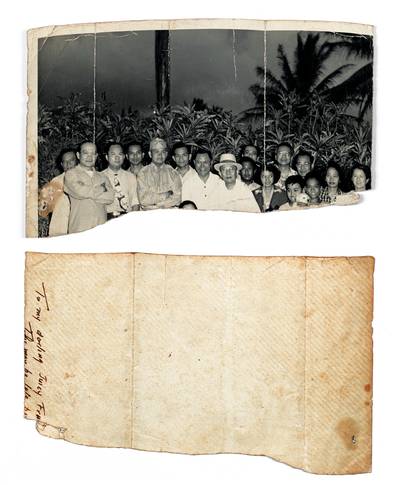

During the Shooting of NAINSUKH (2010). Credit: Manish Soni

Sourav Roy writes, edits, researches in and translates between Bengali and English. A Visual Studies scholar, he is currently researching queer, bengali language creative content production online.

Time-Travelling With a Flying Machine

A flying machine was ready to leave the early colonial court of Mewar, palaced at Udaipur, Rajasthan, India. Only it wasn’t. Colonel Maharaja Sir Sajjan Singh GCSI - The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India, the Maharana of the princely state of Udaipur (r. 1874 – 1884) was worried. The owner of the foreign aircraft, a visiting dignitary, failed to get it airborne even after repeated attempts. It was a crisis of royal hospitality. This very early era novelty of a flying machine1 procured at great effort and expense was like an immense alien bird refusing to budge in the strange air of another planet. The Maharana called the prime artist of his court, the chief of his art atelier. He had recently been sent to Europe to learn the modern visual arts, but aviation arts were definitely not under his purview2. Yet, after a few breath-taking minutes of tinkering and fiddling, he was able to fix the problem3.

What is the ‘artist-ness’ that makes artists, artists? Are they naturally polymaths? Is it their products or their process that makes them artists? Are they just a special kind of artisans? Beyond the usual suspects – persistent myth of god-like skills, mysterious personal genius or a unique combination of patronage-persistence-happenstance – it is only lately that it has been referred to as “creative labour” or “artistic process”.

About 369 years earlier, another court artist in Europe was jotting down his tinkerings and fiddlings about flying machines in the Codice sul volo degli uccelli (Codex on the Flight of Birds, 1505-1506). While being under the employ in the atelier at the court of Milan, Italy, the idea of military aerial reconnaissance inspired Leonardo of the village Vinci into investigations of flight. It would, unfortunately, remain flights of fancy till many, many years later.4

In the Chitra Sutra section of Vishnudharmottar Purana, an encyclopedic entry written between the early 4th century CE and early 6th century CE, there is an oft-quoted conversation. King Vajra asks Sage Markandeya about the nature of true expertise of a visual artist. He was informed that mastery on visual arts can’t be attained without the mastery on dance (because it is the original art of representations), which in turn can’t be attained without the mastery on instrumental music. That, in turn, can’t be mastered without mastering vocal music; vocal music can’t be mastered without mastering the recitation of poetry and prose. And those can be mastered only with the knowledge of metres and measurements.

On the other hand, the mastery of visual arts is more of an unconscious process, according to Plato, so it is not only unremarkable but also dangerous. In today’s language, it is a special kind of potent ignorance, a ‘black box’ that creates a powerful false resemblance to the real thing it is depicting. As he explains in Republic – even a flautist will have more in-depth knowledge of a flute compared to a flute-painter who literally creates a surface impression of the same for gullible viewers. Both are obviously inferior in the knowledge of flute as compared to a flute-maker. So, instead of Sage Markandeya in the 4th Century CE, if King Vajra asked Sage Plato ( c. 427 – 347 BCE), he wouldn’t have gotten much encouragement. The initiation of aircraft won’t have broken any new ground either.

What is the ‘artist-ness’ that makes artists, artists? Are they naturally polymaths? Is it their products or their process that makes them artists? Are they just a special kind of artisans? Beyond the usual suspects - persistent myth of god-like skills, mysterious personal genius or a unique combination of patronage-persistence-happenstance – it is only lately that it has been referred to as “creative labour” or “artistic process”.

“The extreme malleability of the concept of process in relation to art poses certain difficulties for analysis. Limiting the concept to the literal physical processes employed by artists reduces it to a narrow consideration of technical concerns, while the concept’s potential for virtually infinite expansion threatens to render it too broad for meaningful discussion. In order to understand the appeal of process as a key concept for contemporary art, it is necessary to take a wide view of its significance in terms of its present and historical usages and implications. In this study, the concept of process is understood and examined in several different ways that are specifically relevant to visual art. Of primary concern are the ways the artist’s working processes have been conceptualized and valued in the Western tradition, particularly during the modern period. This topic is connected with much broader issues raised by labor in general, especially the relationship of manual work to both intellectual and mechanical labor. Integrally related to conceptions of the artist’s working process are also conceptions of the artist’s identity as an individual engaged in work processes. Understood in this way, the artist’s identity becomes a model for conceiving the physical, psychological, social, and philosophical significance of labor, often specifically manual labor. Considering artistic working processes also leads to examination of those who engage in artistic processes but are not necessarily considered artists, such as craftspeople, students, and amateurs, and the effects such engagements have on both the definition of art and artists, and the social role of art making.”5

Artist Playing Artist, Art Historians as Filmmakers, Artistic Process as Cinematic Device

Art history tells us that finding a timeless, space-neutral ‘artist-ness’ for artists is pointless, nay, anti-historical. Like ‘Art’ and ‘Artist’, ‘Artist-ness’- what makes artists ‘artists’- is a function of time, space, society, culture and the ‘art world’ 6. Using ‘Artistic Process’ or ‘Artistic Labour’ as an essence of ‘Artist-ness’ comes with its own set of art historical warnings.7

But despite the art-historical warnings, artist biopics have nevertheless attempted to capture the artistic essence of visual artists from many eras and varied locales. The question remains, is an individual artistic process or artistic labour, an individual artist-ness, very different from the romantic and nebulous individual artistic genius? What is there to view for an artist viewer and non-artist viewer watching an artist’s biopic from another time or space if they are viewing for artist-ness?

“The artist biopic is a popular form, and while extending the work of art biography into another medium, it does not seek to supplant it. Seldom does advance the art historical debate, and, barring rare exceptions like Peter Watkins’ Edvard Munch (1974), it does not publicize any new information about a given artist. Such films may offer novel interpretations of their subject, but these are rarely of a scholarly nature. As an instrument for popularizing art history, the artist biopic is involved in a constant negotiation between factual accuracy and dramatic value, between the particulars of a specific life and universalist human-interest narratives, between truth and convention.

The biographical film’s emphasis on the individual is even more pronounced when its subject is a painter or a sculptor. The artist biopic as a genre is deeply anchored in a Romanticist view of creation in which the artwork is taken to be the outward expression of the creator’s inner world, divorced from sociohistorical context and independent of the kind of art in question. This outlook is certainly not the invention of the cinematic medium. Griselda Pollock writes:

“The preoccupation with the individual artist is symptomatic of the work accomplished in art history – the production of an artistic subject for works of art. The subject constructed from the art work is then posited as the exclusive source of meaning – i.e., of ‘art,’ and the effect of this is to remove ‘art’ from historical or textual analysis by representing it solely as the ‘expression’ of the creative personality of the artist.”

It is understandable then that popular artist biographies, in literature as much as in cinema, turn to “eras in which historical conditions made possible the formation of the identity of the (proto-)modern artist as an independent individual.” The Renaissance period, which coincides with the rise of civic humanism and the formation of the secular Western subject, is a fertile fishing ground, but so is every art movement from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, when the signature of the artist begins to occupy an increasingly central place in the story of art.”8

The film diminishes the biographical details and even dialogues to a minimum and yet keeps the chronological trajectory of the film Nainsukh’s life-sized. Thus, the filmmakers erase Nainsukh’s heart and soul, yet don’t reduce but elevate him to an ‘eye’. It opens up the viewer, whether artist or not, to creatively imagine the terms of identification with the artist’s persona and his process.

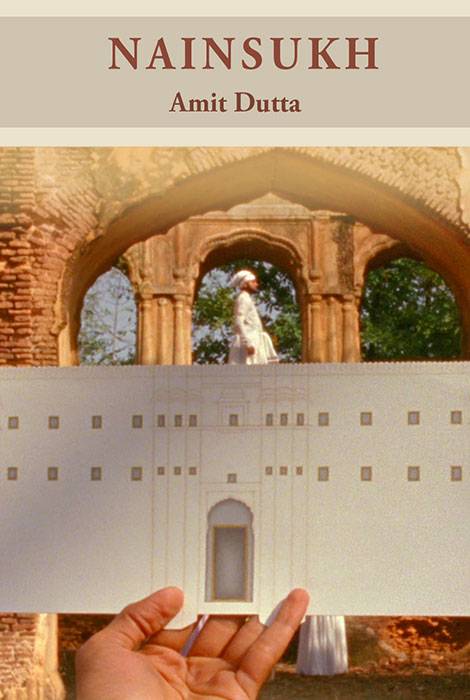

Nainsukh (2010), recently included in the New Yorker’s unnumbered ‘Best Bio-Pics Ever Made’9, makes the film sound pretty, well, biographical: “The eighteenth-century Indian painter of miniatures a master of graceful portraits, fine-grained architectural views, assertive panoramas, and turbulent action is presented here in a form that’s as much a matter of cinematic modernity as of classical echoes. Nainsukh, trained in his father’s workshop, rejects his father’s lessons and leaves home to seek both his style and his fortune. Dutta films the landscapes and the characters of Nainsukh’s life with an aptly painterly and lyrical manner, looks with rapt wonder at the hairline tracings of the artist’s preternaturally controlled brushstrokes, finds the artist’s greatest innovations inseparable from the freedom that he seeks in life, and spotlights the vehement conflicts (including with new patrons) that disrupt art and life alike.” But produced by an Art Museum (Rietberg Museum, Zurich), steered by two premier Art Historians (Late B N Goswamy, Eberhard Fischer)and directed by an avant-garde director (Amit Dutta) and the titular role acted by a third-generation Indian painter of miniatures (Manish Soni), is not a run-of-the-mill way of representing an artist and the artistic process.

Woven on vast art-historical research, this film takes its attention to historical details seriously and lightly at the same time. “A marriage of granite and rainbow”, the imaginative leaps it takes in the narrative are not to make up for gaps in art history. The film diminishes the biographical details and even dialogues to a minimum and yet keeps the chronological trajectory of the film Nainsukh’s life-sized. Thus, the filmmakers erase Nainsukh’s heart and soul, yet don’t reduce but elevate him to an ‘eye’. It opens up the viewer, whether artist or not, to creatively imagine the terms of identification with the artist’s persona and his process.

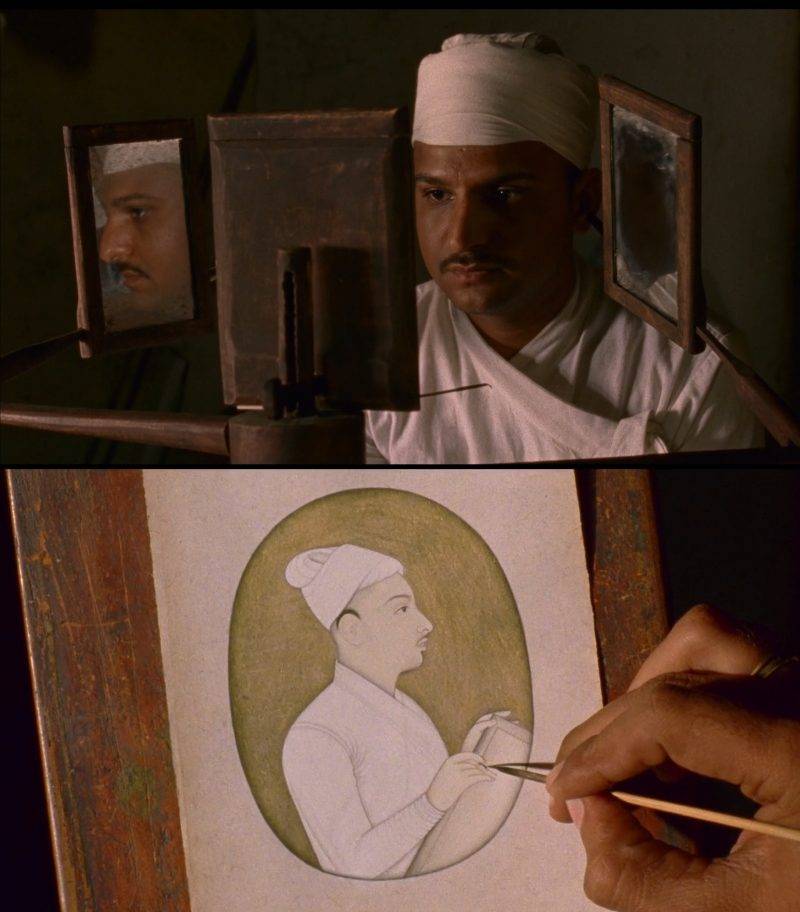

“We see Nainsukh at work throughout the film, working on underdrawings, making sketches from nature, surrounding himself with mirrors to draw portraits.”10 Although the script temporally traces and displays Nainsukh’s most celebrated paintings, the film is anything but a moving picture variety show. The film also opens up the artifice of art-making to the viewers. In this case, the inherent idealisation and grandeur are added to the original miniature paintings. The patron Balwant Singh from Jasrota, being merely a minor royalty, had been depicted by his visual chronicler Nainsukh as a significant regal presence with fineries and properties commensurate with a contemporary emperor. By bringing the film back to the original setting of the palace, now dilapidated, the filmmaker recreates and reimagines the paintings – how things might have been just before it was committed the paper and ink.

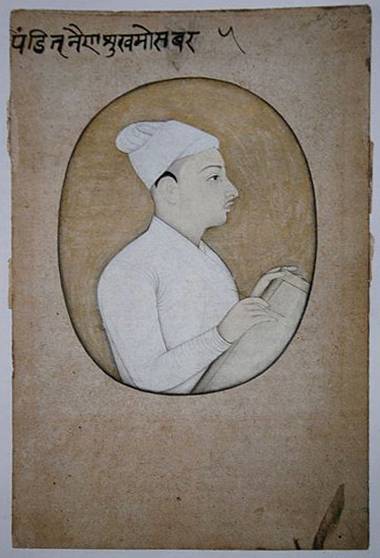

Self-portrait of ‘Nainsukh of Guler’ (c. 1710 - 1778), painted c. 1730. Credit: Wikimedia

Film Poster of Nainsukh (2010), directed by Amit Dutta, written and assisted by Late B. N. Goswamy and Eberhard Fischer, titular role acted by Manish Soni. Image courtesy of Toronto International Film Festival

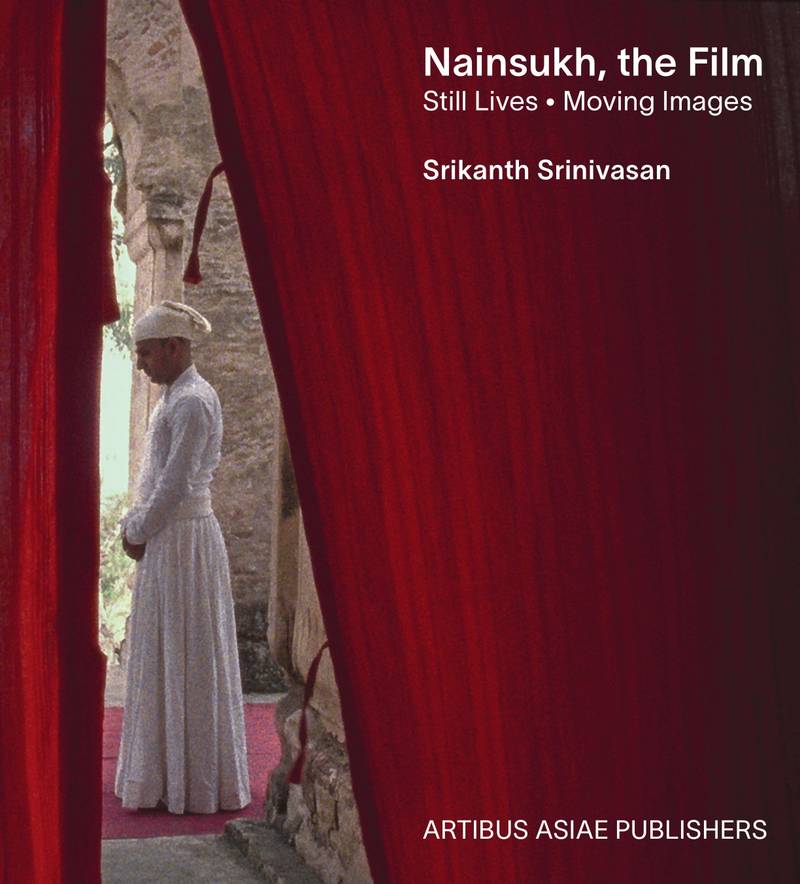

Front cover of the book Nainsukh, the Film: Still Lives, Moving Images, written by Srikanth Srinivasan, published by Artibus Asiae Publishers, 2023. Image courtesy of the author.

‘Nainsukh’ (Manish Soni) working on his self-portrait using a mirror set-up. Screengrab from Nainsukh (2010). Image sourced from Vimeo

“…the choice of setting the historical narrative within the current-day, weather-worn Jasrota palace results in productive frictions between the story set in the past and the material surfaces of the present. This incongruence also reflects the chasm between Balwant Singh’s actual financial status and the lofty aspirations discernible in his portraits. In one scene of the film, Nainsukh is seated on a destroyed pillar, painting a flattering image of his patron’s grand court that belies the reality around him. The ruins, hence, offer a sardonic outlook towards the narrative that is distinct from the attitude of the characters themselves. They tell us, as it were, that if the dilapidated palace was not recreated as a glorious period set, it is because there were no marvels to begin with." (…)

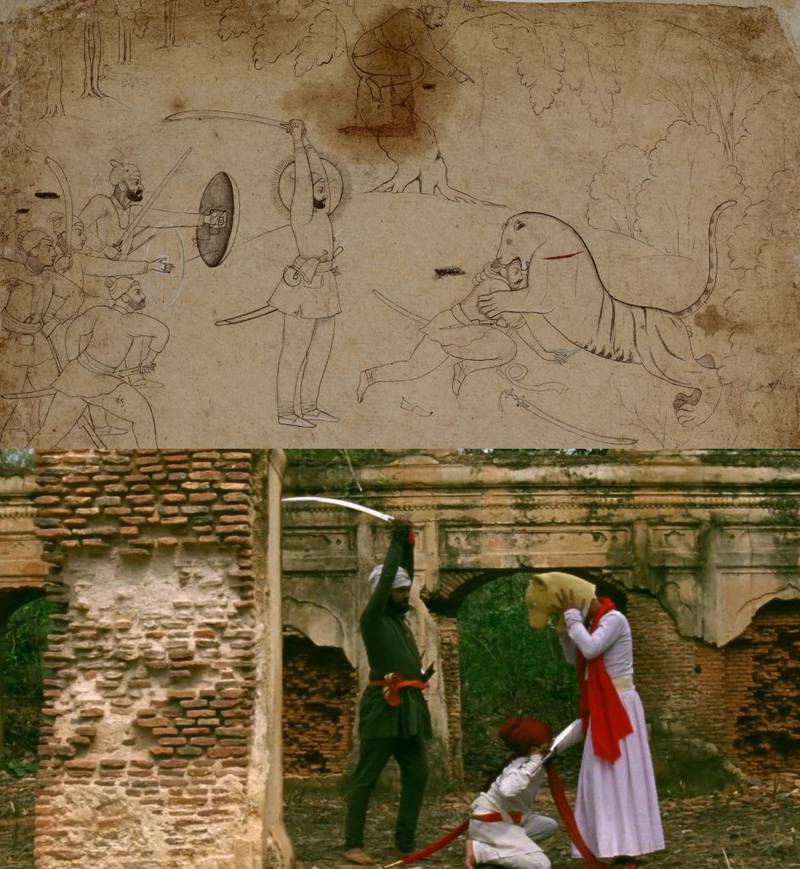

"The difference in the nature of the media involved, finally, imparts an opposing set of tensions to the film’s images. Nainsukh partakes of a fundamental contradiction common to movies dramatizing an artist’s work. On a basic level, the film is a self-confessed fiction based on paintings that have a concrete existence in the world. Recreating Nainsukh’s compositions with real people in real locations, however, its pro-filmic re-enactments possess an ontological reality that surpasses those of the events and personalities portrayed in the pictures. Nainsukh’s conversion of life into paintings and Dutta’s reconversion of these paintings back to life, but with a different shade of meaning, help install a critical distance between the two media.

In reimagining the folios as fictional scenes orchestrated by the painter, Nainsukh points out the pitfalls involved in taking them to be faithful transcriptions of reality. Its reinterpretation of a fierce hunting picture as an instance of amateur theatre or a poetic night-time scene as playacting in a studio serves to reinforce (B. N.) Goswamy’s argument that Nainsukh’s art drew as much from artistic convention as from direct observation. But this revisionism is not done in a spirit of derision. The film’s address is loving and respectful, which is why its ironies are moving, illustrating as they do the bittersweet gap between Balwant’s ambitions and his circumstances.

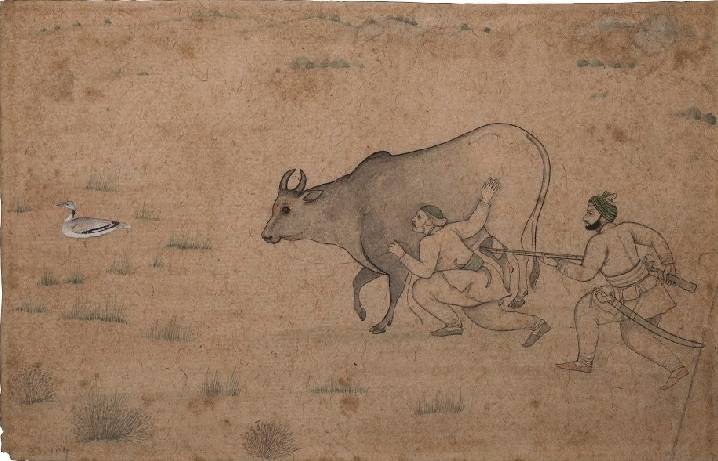

There is, in fact, enough in the paintings themselves to suggest that Nainsukh may have had some fun in exaggerating the reality in front of him or inventing one anew. The mismatch between means and ends in, for example, A Partridge Hunt, where Balwant sets out with what amounts to an entire army to shoot game, or Stalking a Duck, in which he devises a buffalo camouflage to slay a sitting duck, seems so gross that it is hard to imagine that the painter did not have his tongue planted in his cheek when he made these works.”10

Nainsukh creating live tableaus for his paintings. Screengrabs from Nainsukh (2010). Image sourced from Vimeo, Google Arts & Culture

Nainsukh Tableau 2, Balwant Singh Shooting Bustard

Casting a non-actor, who is a practising artist in the same tradition as Nainsukh’s in the titular role created new avenues of artistic self-representation and depiction of the artistic process cinematically. Manish Soni went on to also become one of the art directors, costume designers and directorial assistants. Eberhard Fischer writes:

“Quite soon, we came to the conclusion that to impersonate Nainsukh, a trained and practising young miniature painter, would possibly turn out to be the best choice: a professional’s way to move and work would appear “right,” and when he as an expert uses the brush to paint, it would not look faked but true and correct. Furthermore, the actor playing “Nainsukh” had to be young for the film (in the opening scene he is about twenty years of age and is around fifty at the end of the film), should have North-Indian features and be somewhat accustomed to the Rajput world of foregone centuries. Our choice was Manish Soni from Bhilwara in Rajasthan, whose father, uncles and grandfather, are renowned miniaturists and pichhwai painters, known internationally as the famous Badri Lal Chitrakar family. Additionally, this young painter who hails from Mewar in Rajasthan, had studied court paintings intensively for internalizing details before re-creating them and had a cultural background still influenced by Rajput court etiquette. Manish knew some facets of the formal behaviour that is now on the vane in most other regions of India. “Nainsukh’s” gestures and movements were therefore not only “correct” in the workshop scenes, but also convincing when acting at the court as a retainer with a special status.” 11

In a personal interview, among several enlightening anecdotes, Manish recounts an incident that brings artistic representation, self-representation, cinematic device, and artistic process to a satisfying confluence.

A key shot in the film depicted the artist painting a sacred river descending in full force from heaven to the earth by the side of a river flowing with similar vigour. The mirroring of the force in the painted and cinematographed flows reflecting in the apparent state of mind of the artist – was supposed to create a unique pathos in the viewer’s mind. But the speed of the river was much slower than intended at the shore. So Manish suggested setting up a ladder in the middle of the speedy flow of the shallow river to be captured by a crane shot. This unique risk involved possible physical damage (not to forget the damage to the costume, which was supposed to be immaculately clean and dry) and the requirement of unique concentration and artistic expertise – that demanded flawless execution of the painting while being perched on the tiny step of the ladder held in place by two men, their muscles straining against the sharp speed of the mountain river.

The complicated shot was successfully taken at a single go.

Manish Soni playing ‘Nainsukh’. Image courtesy of Manish Soni

Manish Soni playing ‘Nainsukh’. Image courtesy of Manish Soni

Manish Soni playing ‘Nainsukh’. Image courtesy of Manish Soni

Nainsukh creating live tableaus for his paintings. Screengrabs from Nainsukh (2010). Image sourced from Vimeo, Google Arts & Culture