Laia Abril: Feelings, On Mass hysteria, 2023. Courtesy: Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire

Sheung Yiu (HK/FI) is a Hong Kong-born, image-centered artist and researcher based in Helsinki. His practice explores the act of sensing through algorithmic image systems he calls Hyperimage. He looks at photography through the lens of new media, scales, and systems to contemplate how cyborg vision transforms ways of seeing and knowledge-making. When he is not making photographs, he writes about photography.

We are living at a tipping point: facing the climate crisis, increasing economic disparity, and international conflicts exacerbated by capitalism and systems of oppression. As we struggle to navigate this social turmoil and, or for those with aspiration, searching for a way to alleviate the situation, self-help experts step in with their advice. There is no shortage of Online self-help content urging us to get fit, get rich, live greener, and become better individuals. Yet, there is a certain insidiousness to self-help advice that diagnoses the individual in the face of systemic failure.

“Maybe the only healthy way to react to a capitalist society is to get sick.” paraphrased the curator of the Festival of Political Photography (or Poliittisen Valokuvan Festivaali, PVF) Anna-Kaisa Rastenberger reflecting on the theme of the latest edition of PVF, Diagnosis. The theme is a double entendre. Firstly, it examines the diagnosis as a social phenomenon. While diagnosis is typically applied to individuals to identify illness, what if society itself is unwell? What if we turn our diagnostic gaze toward society as a whole instead of scrutinizing individuals? Rastenberger asked whether the illnesses, mental or physical, are a manifestation of a larger sociological problem.

Secondly, it refers to photography itself as a tool for social diagnosis. The theme expresses the festival’s ambition to break away from a conventional position in Finnish photography education that conforms to market demands and the status quo rather than challenging them. With the festival’s co-founder Sanni Seppo, PVF advocates for photography to participate and shape democracy by activating citizens as actors of decision-making in the distribution of power and resources in a society. This ethos echoes Ariella Azoulay’s concept of the civil contract of photography, which contends that photography can serve as a vehicle for political agency and resistance. Azoulay argues that even individuals with flawed or nonexistent citizenship can harness photography to pursue political engagement and challenge existing power structures.

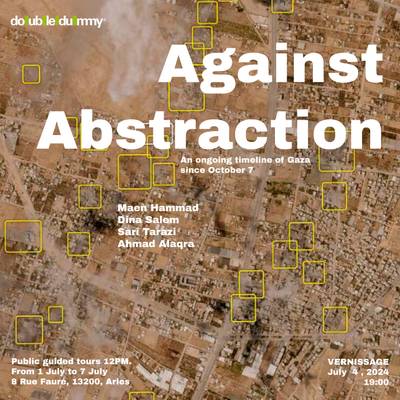

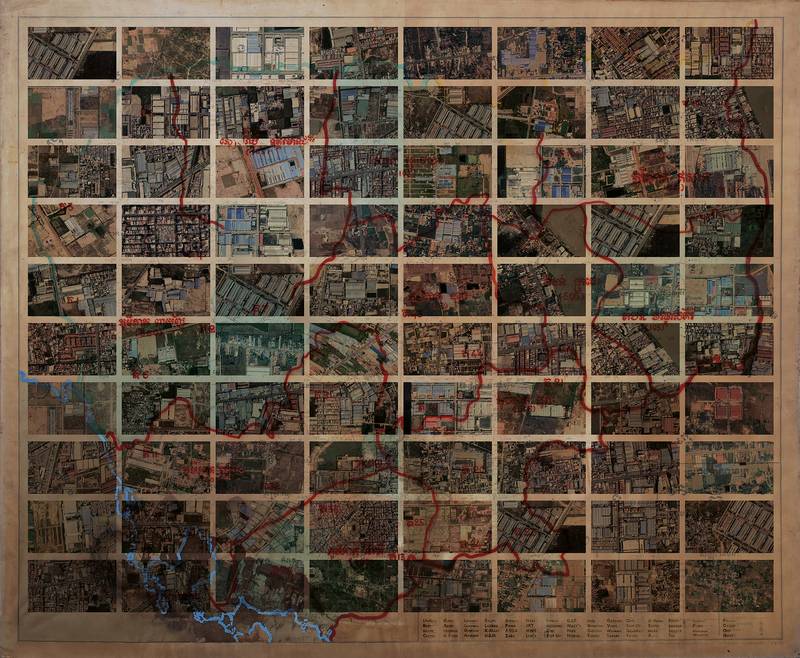

Laia Abril: Case Piece Cambodia, On Mass Hysteria, 2023. Courtesy: Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire

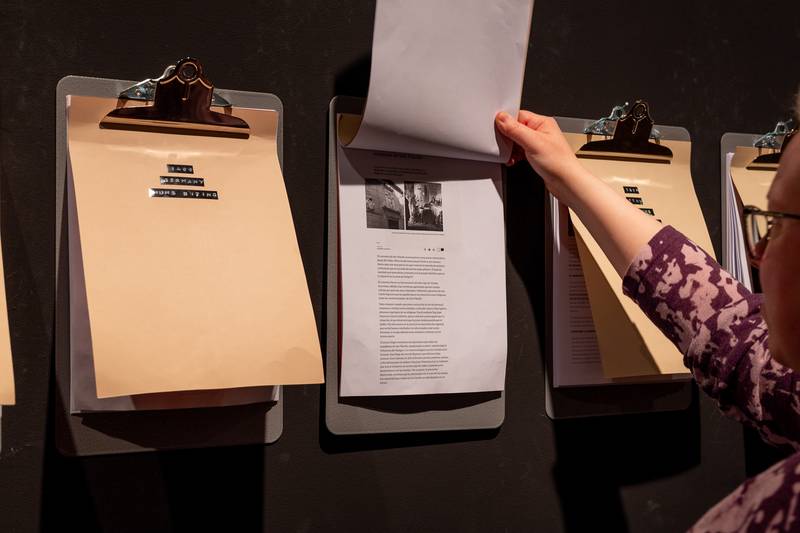

Building upon similar sentiments, Laia Abril examines the diagnostic gaze in the On Mass Hysteria project featured in the Festival of Political Photography exhibition at the Finnish Photography Museum. For this research-based project, Abril switches the focus from the pressure on the individual to the society. Rather than focusing on individual psychology and trauma, Abril uses photography to argue how racism, misogyny, and oppression literally make us sick. Abril collected case studies of mass hysteria worldwide. Dozens of news clippings are neatly organized on clipboards along the wall, leading the audience into the main exhibition space. One folder contains a screenshot from an online article that defines mass hysteria as a mass sociogenic illness—a phenomenon where a group, usually a close-knit community, simultaneously exhibits the same symptoms. These symptoms can manifest in the form of uncontrollable behaviors, such as tics and hiccups. There are no obvious physiological causes for mass hysteria. The infectious nature of mass hysteria, despite the absence of a pathogen, adds a layer of mysticism and irrational fear to the phenomenon.

Installation view from Laia Abril: On Mass Hysteria at The Festival of Political Photography, The Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki. Photo: Virve Laustela

Mass hysteria is a lesser-known phenomenon that has been documented throughout history. The earliest documentation dates back to 1374, when the dancing plague affected dozens of medieval towns scattered along the valley of the River Rhine. Hundreds of people were seized by an agonizing compulsion to dance. The epidemic quickly spread to northeastern France and the Netherlands before subsiding after several months. Today, mass hysteria continues to manifest and spread in novel ways. For example, in 2022, TikTok Tourette Syndrome spread across the short-form video social media platforms among teenage girls. They began experiencing Tourette-like tics after watching influencers with similar symptoms.

Laia Abril focuses on mass hysteria cases where women and girls are the bodies being diagnosed. This choice is typical of Laia Abril’s repertoire, who has embarked on a critically-acclaimed trilogy titled A History of Misogyny, consisting of three parts: ‘On Abortion’ and ‘On Rape’, in addition to the most recently-shown ‘On Mass Hysteria’. In each project, Abril tackles the system of female oppression globally and historically. Working with psychologists, anthropologists, and sociologists, Abril’s expansive photographic survey presents multiple perspectives on misogyny.

The main exhibition space features multiple partitions, each providing more elaborate case studies on particular instances of mass hysteria. On the outward-facing side, there is a short description of each case, contextualizing the black and white documentary photographs inside. One room features the Paralysis epidemic in a Mexican Catholic boarding school in 2007, where nearly 600 girls from a Korean Catholic all-female school lost their ability to walk straight. These girls attended the school seeking refuge from potential poverty, abuse, and teen pregnancy. Initially, no physio-neurological cause was found to explain their strange behavior. However, as the case gained media attention, it was revealed that the girls may have acquired psychological trauma from being exposed to the strict Catholic regime at school. The wall text includes Mexican anthropologist Josefina Ramirez’s description of the Catholic school: a cultural system of morality where emotions are controlled and imposed on the bodies of the ‘inmates.’

Installation view from Laia Abril: On Mass Hysteria at The Festival of Political Photography, The Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki. Photo: Virve Laustela

Installation view from Laia Abril: On Mass Hysteria at The Festival of Political Photography, The Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki. Photo: Virve Laustela

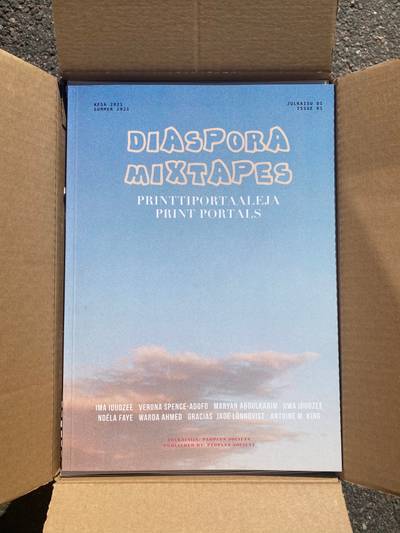

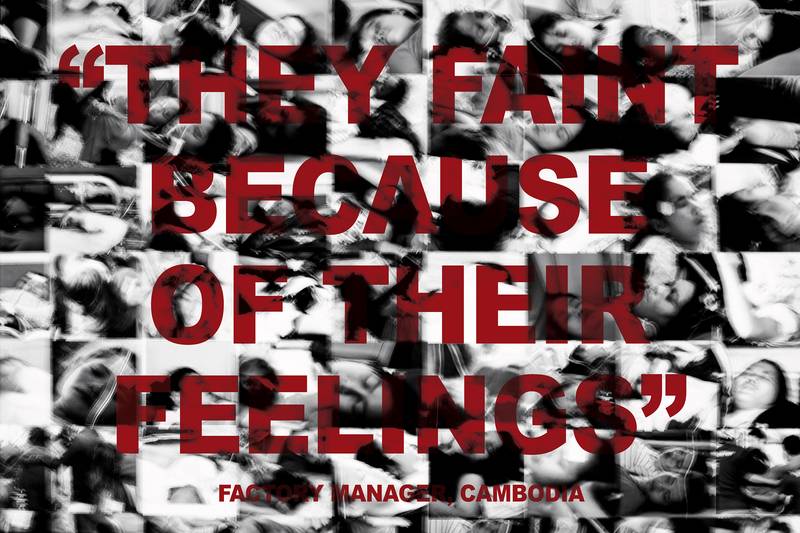

Across the room stand numerous framed collages, composed of blurry black-and-white photographs of the faces of the afflicted in a grid-like arrangement, overlaying on top are quotations in stark red block letters. These quotes are credited to authoritative figures, often males, such as factory owners and political leaders, who dispassionately gave their diagnosis on the condition of these women. Not realizing the social quagmire ensnaring these young women, they hastily dismiss their symptoms. In analogous instances of collective hysteria, similar dismissals echo: THEY FAINT BECAUSE OF THEIR FEELINGS. THEY WEAR TOO MUCH MAKEUP. Abril brings these superficial diagnoses to the fore, indicting their apathy and their inability to understand the psychological distress these women had gone through. On the other hand, her narrative rebrands mass hysteria as an unconscious language of protest through which our bodies protest on our behalf, as one of the experts she interviewed pointed out.

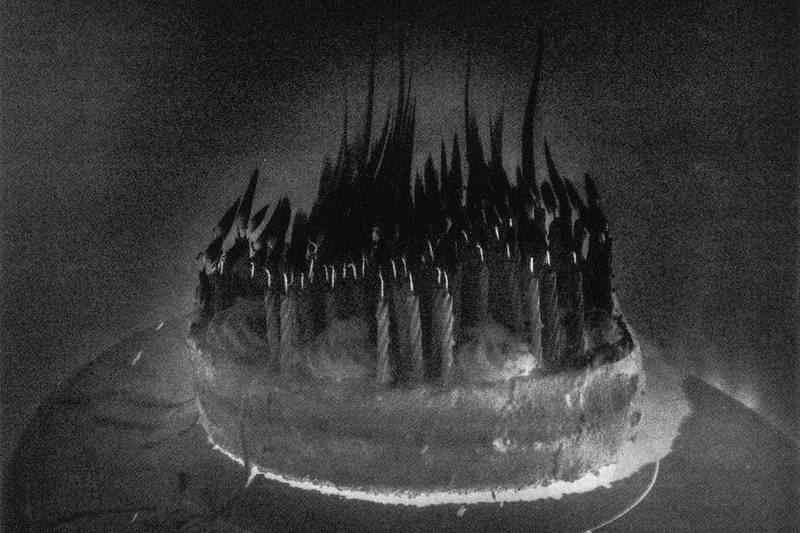

The grid arrangement of blurred portraits brings to mind the clinical language in Jean-Martin Charcot’s categorization of the purported symptoms of hysteria in female patients at the Salpêtrière hospital. Dubbed the father of neurology, Charcot was the founder of a school and a whole movement of thought—“the School of the Salpêtrière,” The French neurologist used drawings and photography to study the neurological disorder of Hysteria, a disease characterized by emotional excess and physical weakness that he insisted is prevalent exclusively to female bodies. The contemporaneous popularization of photography during his research gave him the tool to document the symptoms systematically. At the same time, photography and its unprecedented power to capture its subject in incredible detail assumed an unparalleled evidentiary role, cementing the visual form as an indispensable part of the empirical scientific process. As Georges Didi-Huberman put it, the convergence of research desire and technological advancement arguably created a focus on the ocular symptoms of hysteria. Charcot amassed a large photo archive of symptomatic patients, a majority of them depict women in exaggerated contorted or convulsed poses, as if to illustrate the intensity of the ‘disorder.’

Laia Abril: Teen’s Pain, On Mass Hysteria, 2023. Courtesy: Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire

Laia Abril: Mass birthday mind series, screenprint, Mexico case, On Mass Hysteria, 2023

The lack of introspection about the societal apparatus—the sexist and paternalistic view of Western medicine—and the hyperfocus on diagnosing the individual led to the wrongful pathologization of the female body. The extra irony, perhaps, is that women and patients from marginalized groups today are more likely to be ignored by medical professionals, as some medical researchers have pointed out.

Yet, as his theory unfolded, the symptoms expanded to other, more subtle behaviors. Psychiatrists at the Salpêtrière meticulously scrutinized a myriad of phenomena, from affected gestures to asymmetrical gazes. The classification of symptoms became so erratic that the entire album reads like a compendium of female figures in every conceivable pose and facial expression. Ultimately, Charcot cannot conclude a specific cause of Hysteria, and he admits that the word hysteria does not mean anything after all. Rather than providing evidence for the existence of hysteria, Charcot’s photographs pathologize the female body and psyche. By presenting women’s bodies as inherently hysterical, Charcot’s photographs contributed to the stigmatization of women and the perpetuation of gender stereotypes in medicine. It was not until almost a century later that Hysteria was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) as a diagnosis in 1980, and experts no longer use this term. Abril’s evocative photo collage suggests that the removal of hysteria from the Manual is far from the end of the story. The bold red block letters, slathering the collage with a poignant hue, murmurs that this history between women and hysteria is not a new one.

The lack of introspection about the societal apparatus—the sexist and paternalistic view of Western medicine—and the hyperfocus on diagnosing the individual led to the wrongful pathologization of the female body. The extra irony, perhaps, is that women and patients from marginalized groups today are more likely to be ignored by medical professionals, as some medical researchers have pointed out. Female patients with endometriosis are constantly being under-diagnosed. They are more likely to be dismissed by their physicians, who carelessly assume they are overreacting to period cramps, leading to delayed treatment. The under-diagnosis might also stem from a prejudiced idea about “women being somehow accountable for their own illnesses.” Paradoxically, the female body is simultaneously being over-diagnosed and under-diagnosed, but almost never with the right intention and never receiving right care. Whether being overdiagnosed for a non-existent disease or underdiagnosed for endometriosis, Abril’s case studies in mass hysteria underscores the intricate politics that permeate the diagnostic process.

Social structure does not only pathologize the female body; it trickles down to every individual being. And capitalism spares none. In Anti‐Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari describe what they call the schizophrenic process. They astutely observe that capitalism operates by continually breaking down and reorganizing social structures and identities, leading to a state of constant flux and instability. They metaphorize the fragmented and disorganized nature of modern capitalist societies as Schizophrenia. Although Deleuze and Guattari did not reduce Schizophrenia to a clinical mental illness, it provides a potent lens through which to apprehend the mental health epidemic as a symptom of capitalism, where the exploitation of labor and competition creates a disconnection and alienation among individuals. Not to mention, the climate anxiety that many of us are experiencing is a direct result of anthropogenic climate change in which capitalist extraction of natural resources is largely to blame. This mass hysteria does not manifest in physical form but in the collective psyche, eroding our very subjectivities. Seen this way, hysteria and schizophrenia are symptoms experienced by individuals that reveal their entanglement with the social structure, or what Deleuze and Guattari called the social machines.

Diagnosis on the individual and the new surge of self-improvement online influencers and life coaches should, thus, be read within the context of a perverted capitalist society that rewards psychopathic behaviors. This insistence on individual responsibility and self-reliance is typical of the neoliberal ideology, which places the onus of success or failure squarely on the shoulders of individuals, absolving society of any responsibility for addressing systemic inequalities.

Attempting to address mental illness solely through individual diagnosis and treatment overlooks the systemic issues at play. That is not to excuse individual responsibility, but the relations between the individual and the society require some rethinking, especially considering the impact of global events, such as climate change, on our lives. We can borrow some insights from ecological thinking, for example, Timothy Morton’s articulation of the relations between climate and weather. In his account, climate is a large-scale phenomenon, while weather is a local manifestation of climate. Climate change has brought extreme weather to different regions, which is itself an effect of global warming. We can experience climate only partially through weather, and weather is a symptom of a larger phenomenon. Similarly, societal problems can manifest in the individual as physical illness or mental disorder. But if we give a diagnosis solely on the individual, even blaming the individual for their illness, then we are no different from the misinformed US Senator James Inhofe, who brought a snowball on the Senate floor to prove that climate change isn’t real.

In many ways, the hyperfocus on individual responsibility is another side of the coin of self-attribution bias. Self-attribution bias is a cognitive bias where individuals tend to attribute their successes to their own abilities and efforts while conveniently assigning blame for their failures to external factors or circumstances. Notably prevalent among CEOs and leaders, this bias often leads them to exaggerate their role in their companies’ success while downplaying the role of workers or other external forces. This cognitive bias leads to overconfidence and excessive risk-taking in an individual. In Western capitalist society, this overconfidence is often associated with leadership skills, unwittingly creating a self-fulfilling prophecy where the more likely a person is to attribute success to themselves, the more likely they are perceived to be a leader material and given managerial roles within corporate hierarchies. Thus, the cycle perpetuates itself, reinforcing the very biases that underpin it.

Diagnosis on the individual and the new surge of self-improvement online influencers and life coaches, thus, should be read within the context of a perverted capitalist society that rewards psychopathic behaviors. This insistence on individual responsibility and self-reliance is typical of the neoliberal ideology, which places the onus of success or failure squarely on the shoulders of individuals, absolving society of any responsibility for addressing systemic inequalities. To be clear, self-improvement per se can be a valid way of pursuing a better life. However, to believe that personal growth alone is the cure-all antidote for life’s challenges and champion that as a universal metric with which to judge others stems from ignorance and arrogance.

Anyone who has played any game with a difficult setting is able to tell you that in easy mode, your skill set affects your performance, but in difficult mode, luck and knowledge become increasingly crucial as the game’s systems constantly present challenges. People from WEIRD countries (western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic) play the real-life game of Western capitalism in the “easy mode,” where their hard work is indeed rewarded without encountering significant obstacles or surprises along the way. The optimism and trust of the capitalist machine, which, if you look closely, will show that the state plays a more important role than ever in the wealthiest capitalist economies today. Think central bank quantitative easing and bailouts. They are state intervention disguised as economic policy under the facade of free-market capitalism.

Exercising, eating healthy, and tidying up your apartment won’t improve your life that much if your landlord is constantly raising rent at every opportunity and your politicians are hellbent on cutting the tax rate of the rich. Dressing moderately does not exempt the victim from rape. In fact, this type of individual blaming is a distraction from the root cause of your misery. Widening economic disparity, climate crisis, oppression, and the mental health epidemic are systematic issues. If the problems that individuals face in their personal lives are rooted in systemic issues, then it is unrealistic to expect them to find lasting solutions solely through individual self-improvement efforts. Individual change is not simply a matter of personal effort but is also shaped by the broader social conditions that individuals find themselves in. Abril’s work highlights this hypocrisy of the oppressor in a perverted patriarchal society in which women are blamed and ridiculed for showing symptoms of distress—Mass Hysteria.