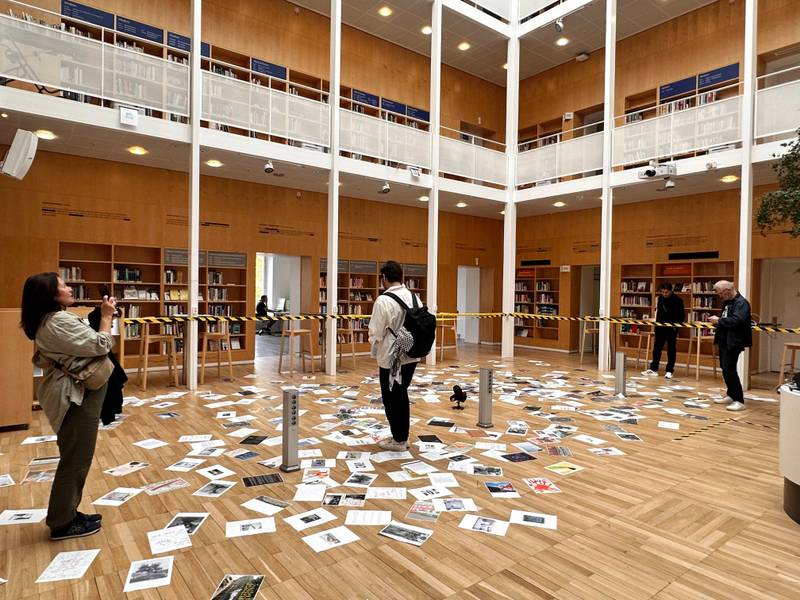

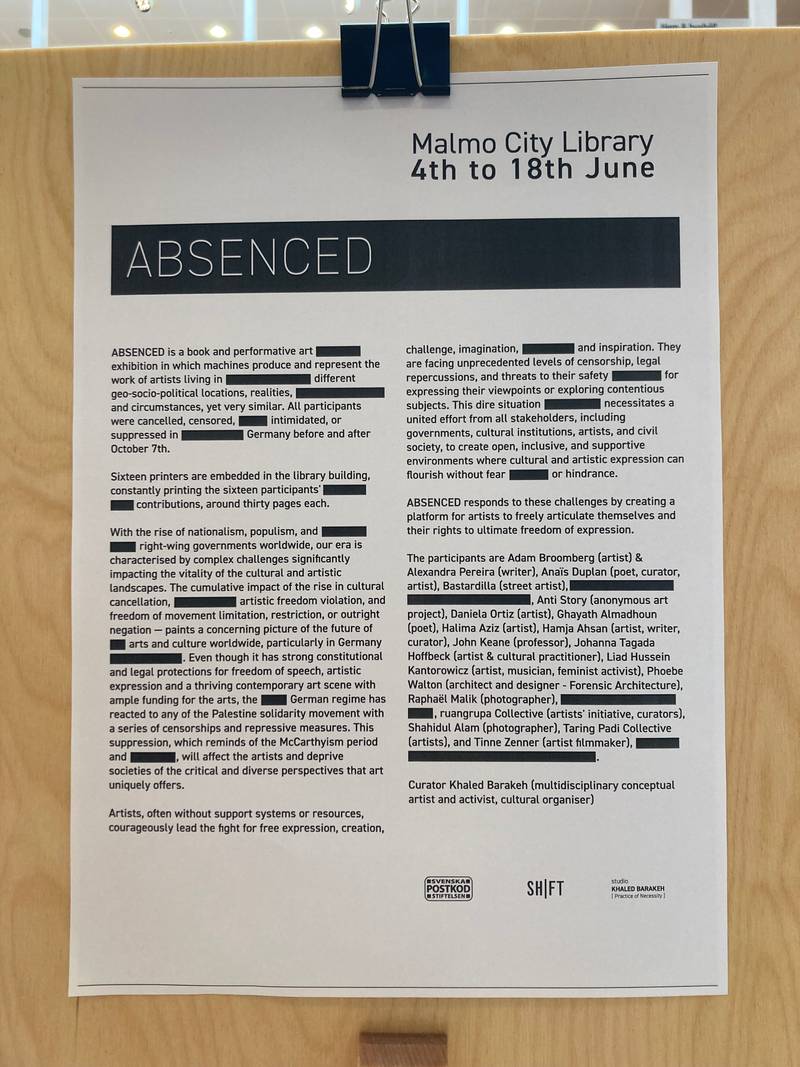

Installation view of the ABSENCED exhibition at the Malmö City LIbrary, Image courtesy of Khaled Barakeh.

Mansi Kashatria is a researcher-writer based between Sweden and India. With a postgraduate in Ethnic and Migration Studies and currently pursuing her PhD. in Culture Studies, she is tracing how the histories and imaginations of select-few contemporary art institutions are shaping their practices. Growing up in a small border town of Punjab, India, she describes her relationship with contemporaneity and global art as having been rather disjointed and therefore critical.

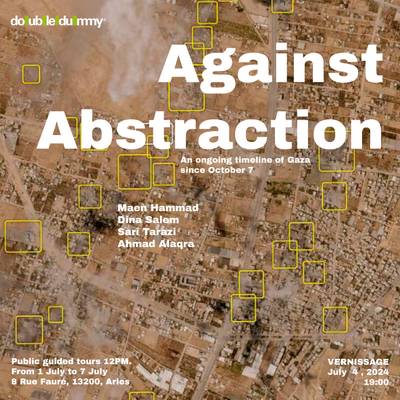

Walking into a contemporary art exhibition at a public library is not entirely unusual for Sweden. Neither is it surprising that Sweden’s third largest city, Malmö, has hosted an alternative song contest, FalastinVision, to protest Israel’s participation in the Eurovision Song Contest 2024. Along with an alarming rise of far-right movements and policies in many parts of Europe and the world, there have emerged resistances and struggles that are exposing the violence inherent in our nation-states and their borders. The exhibition ABSENCED, curated by Berlin-based conceptual artist and cultural activist Khaled Barakeh which opened on June 4 at Malmö City Library, is an effort to showcase some of these expressions of resistance.

In ABSENCED machines reproduce and represent the works of those artists who have been either ‘cancelled, censored, intimidated, punished, or suppressed in Germany before and after October 7th.’1 The exhibition is the Swedish iteration of a larger artistic programme called ‘Routes of Resistance’ that has brought together practices of cultural workers from Mexico, Uganda, South Africa, and Sweden. While the bigger project is housed at SHIFT (Safe Havens Freedom Talks), a non-profit organisation and an open platform dedicated to safeguarding artistic freedom, both the exhibition and the project are funded by non-governmental foundation Svesnka Postkodstiftelsen. Khaled was invited by Fredrik Elg on behalf of SHIFT, which he co-founded, although he also works part-time at Malmö City Library.

As one enters the library, to the left and one floor up, an inner courtyard called Slottet opens up for passersby. For ABSENCED, the courtyard was surrounded by 16 printers that were stationed another floor above and were programmed to spew out prints of many artworks and letters at regular intervals. Over the two weeks that all the printers had worked incessantly, a pile of papers had gathered. Through that pile, a narrow path led the visitor to a bundle of booklets that had compiled all 16 artists’ short biographies, incidents of cancellation, and the works they had sent for the exhibition. A restricting tape going all around the exhibition somewhat marked/delimited the space of the exhibition but was actually not part of the initial curatorial plan. But as someone fell on the pile of papers in the first few days of the exhibition, unfortunately, that tape was introduced and warning signs put up. An unintended outcome being an adhesive tape, it kept catching many papers falling from the floor above, effectively visualising the process of restriction as it unfolded for several of the artists represented there.

Installation view of the ABSENCED exhibition at the Malmö City LIbrary. Image courtesy of Khaled Barakeh.

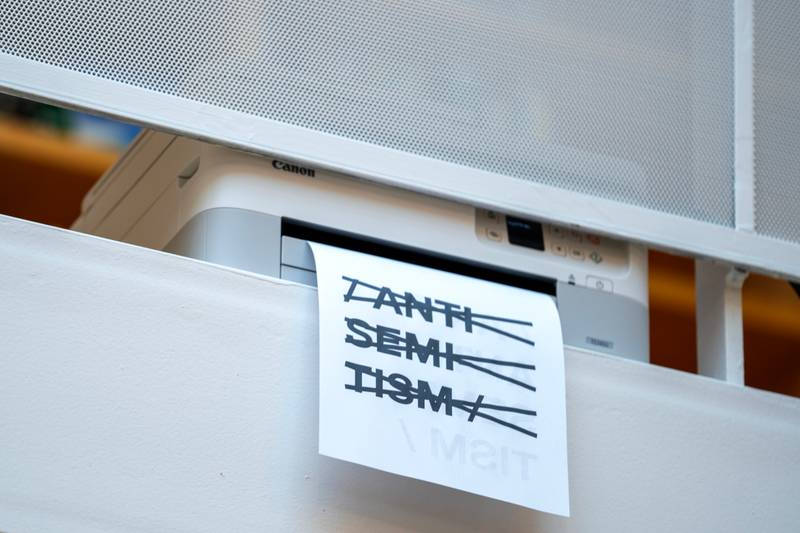

Restrictive adhesive tape catching the falling artwork prints. Photo by Mansi Kashatria.

At first glance, the pile of papers on the floor seemed random and chaotic but had an allure to engage with it. The prints were a mix of artworks, statements, events, poetry, and scribbles, and personally, the more I stayed with the papers, the clearer the narrative between them emerged. Similarly, the participants in the exhibition were a varied group of cultural producers, such as visual artists, academics, poets, and architects. They were also not chosen based on ‘traditional criteria like the artwork subject, medium of expression, career stage, gender, geographic location, or age’, as Khaled shares in his curatorial vision for the exhibition. So, the common thread between all the works and participants represented at ABSENCED was instead the censorship and intimidation incidents that occurred in Germany because of their pro-Palestine activities before and after October 7th.

The work made it apparent that artistic freedom got curbed in different public and private spheres, such as universities, art institutions, festivals, and even street art. For example, works sent in by Adam Broomberg (artist) & Rafael Gonzalez (artist), John Keane (professor), and Phoebe Walton (architect, designer at Forensic Architecture) were cancelled by academic institutions. The incidents of cancellation for Daniela Ortiz (artist), Ghayath Almadhoun (poet), Liad Hussein Kantorowicz (musician, feminist activist), Tinne Zenner (filmmaker), Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck (cultural practitioner) happened at art institutions. Even public festivals, street art or big art exhibitions such as Documenta were involved in intimidating artists and groups like Bastardilla (street artist), Shahidul Alam (photographer), ruangrupa (artists’ initiatives, curators), Taring Padi (artists’ collective), Raphaël Malik (photographer), Halima Aziz (artist), and Hamja Ahsan (artist, writer, curator).2

Printer in action. ABSENCED. Slottet, Malmö City Library, Malmö. Photo by Jartina Shora.

The extent of ongoing and increasing repression of artistic freedom in Germany had caught some of the visitors by surprise. With each story of censorship brought to ABSENCED, Germany’s otherwise strong frameworks for expressing political opinions and artistic creativity got called out. Moreover, with a minimum or no interference from the curator as well as the library staff in the choice of works sent in by the artists, ABSENCED created a platform for artists to freely articulate themselves and their rights to ultimate freedom of expression.

Who is neutral, and who is a threat?

The decision to not interfere in the selection of ABSENCED ’s content by the library staff follows from an established approach and practice of protecting sensitive and controversial topics. In May 2022, Andreas Paulsson’s exhibition Alla är vi nakna (We are all naked), displayed at the library, was vandalised by a man because of its ‘exposing’ and ‘offensive’ content. In response, the library employed a guard, although it did not find the incident dangerous.3 The same year, Malmö City Library started a section called Känsliga Ämnen (Sensitive Topics) in connection to Malmö City Pride intended for people who are vulnerable and need a safe space to search for knowledge for themselves without having to approach the library staff.4 Another policy worth mentioning here is Malmö City Library becoming one of the first few libraries in Sweden in 2013 to allow undocumented people to access and borrow from the library’s resources.5 These three events show that the library has been building a practice of tolerance and readiness to support artistic and political pluralism. But precisely this nature of openness tends to result in reflecting the contestations of a polarised society within the walls of its institution. For example, in 2023, the right-wing newspaper Bulletin accused the library of showcasing a copy of Mein Kampf in Arabic when the actual book on the shelf happened to be a biography on Hitler by an Egyptian author.6 The library also stated in their response that a public visitor probably put it on one of the display stands. This shows their persistence in asserting the right of a public library to host controversial content in their spaces. In the case of ABSENCED, Khaled shared a similar curatorial challenge.7 His concern was finding a balance between reproducing the socio-political context of art censorship in Germany while engaging with the audience as well as not jeopardising artistic freedom in the process.

So, even though the exhibition has a specific event and socio-political concern that focusses on the censorship of pro-Palestinian activities by German institutions, the exhibition getting an invitation and presentation in Malmö, Sweden, adds another layer of context to it. This layer is made up of a longer historical relationship between Sweden and Germany. If one travels from Trelleborg, the southernmost port of Sweden, to Sassnitz, the northern entry port to Germany, it is merely a journey of 125 km. However, it is not just the territorial proximity that binds these two countries together but also the movement of people, based on Sweden’s conditional interpretation of its neutrality and freedom of expression for people seeking refuge or work opportunities.

There have, of course, been countless movements of people between the countries in both directions throughout history. German ‘experts’ were invited to boost the economy of the mediaeval Swedish proto-state. In the Thirty Years War, Sweden invaded and annexed large parts of Germany, some of which remained Swedish territories into the 19th century. During the 20th century, many famous Germans sought a new home in their northern neighbour, temporarily or permanently, and for very different reasons. Germany’s military commander in World War I, Erich Ludendorff entered southern Sweden illegally in 1918 after the country’s defeat. Wolfgang Kapp, the far-right coup leader, fled to southern Sweden in 1920 after the failed ‘Kapp’ putsch. Hermann Göring of the Nazi Party was treated repeatedly in Stockholm for his morphine addiction in the 1920s. Later, in the wake of Nazi Germany, artistic, Jewish, or political refugees like Bertolt Brecht, Lotte Laserstein,8 Ernst Cassirer, and Willy Brandt spent more or less time in the country. Many Germans who made quite the impact at home and internationally ‘owe’ their survival to the alleged neutrality and openness of the Swedish state. But it is an openness that comes with an appendix.

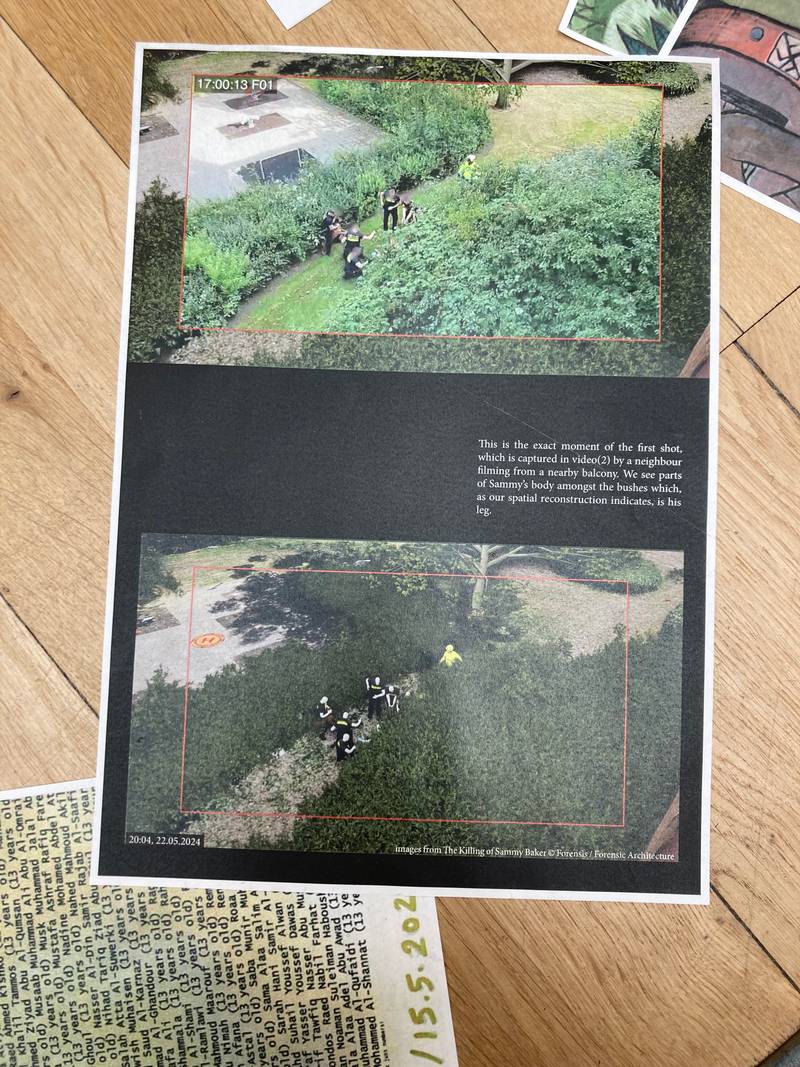

Artwork by Phoebe Walton as found in the exhibition display pile. ABSENCED. Slottet, Malmö City Library, Malmö. Photo: Mansi Kashatria

Exhibition text, ABSENCED. Slottet, Malmö City Library, Malmö.

Phoebe Walton, one of the artists/architects participating in this exhibition, was scheduled to give a lecture on behalf of Forensis e.V. and Forensic Architecture, where she would have presented the ‘Investigation into the Killing of Sammy Baker by the Dutch Police.’ But the lecture was cancelled by The Rector of RWTH (Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule) Aachen, noting the impossibility of maintaining a ‘neutral scientific critical discourse’ together with responding to global political tensions.

Phoebe’s work emphasises how institutions of knowledge use silencing as a tactic to uphold the presumption of ‘neutrality.’ This high ground of assumed neutrality adheres to the idea of universal humanism while standing on many voices oppressed and silenced.

An artist such as Danish Lars Vilks, who repeatedly received death threats and attacks because of his Islamophobic drawings of the prophet Muhammad, will never come near the space of being perceived as a threat to ‘society’ or ‘democracy.’ At best, such artistic provocations might be critiqued for their potential harm to specific groups within that society, but never democratic society at large, with its supposed universal free speech. Only in the case of the Qur’an burnings, an infamous phenomenon repeatedly conducted in many Swedish cities, may the notion of a threat to the broader society, ‘civil order’ or ‘public sphere’ become relevant. On the other hand, ‘provocative’ artists and artworks highlighting the censorship of a supposedly universally inclusive, democratic society—for example, Germany—always stand a chance of receiving the state support previously provided to figures like Vilks. However, they will also always run the risk of being identified as ‘threats’ to society - something that Vilks and his likes have never suffered. As Ariella Aïsha Azoulay writes, in the case of the Islamophobic provocations of the French Charlie Hebdo magazine, ‘freedom of speech’ was understood as their intrinsic right, regardless of the fact that it is not shared by all members of the body politic.’9 And it is in relation to this discrepancy between a) a ‘threat-to-all’ (state/society/common/institutions/law) and b) a ‘threat-to-some’ (irrelevant/minorities/others) that ABSENCED needs to be read.

Defying the alleged and ostensive ‘universal position of the artist’ (Azoulay), the exhibition rather points to the institutional exclusion of art that goes against status quo positions or, in other ways, calls out major contradictions in a society like that of Germany. When brought to Sweden, Khaled made a decision to abstain from conventional spaces of art exhibition in favour of a possibly less ‘elite’ and ‘canonical’ arena: the public library.

The Presumed Democracy of Swedish Public Institutions

In a conversation with Khaled, he noted, “post World War II, many Western countries shifted towards progressive ideals, influencing artistic spaces that started attracting those who aligned with those values. Libraries on the other hand, as community hubs, are inherently public and more inclusive spaces, accessible to a broader diverse audience. For “ABSENCED,” the use of printers and paper to create the artwork symbolically underscores the dissemination of ideas and the preservation of culture—key aspects of any library’s mission.”

Choosing a Swedish public library as an exhibition space comes with a set of additional associations and connections. The public library as an institution has a significant lineage pointing to the country’s modern history of popular movements and civic education, popularly known as folkrörelser (People’s Movements) that were aimed at creating ‘democratic citizens.’ In addition, staging the exhibition in an open yard of the library made it highly accessible, free of charge, and at the same time a chance encounter rather than a committed visit. A diversity of people could pass through and still witness the printers spewing out prints of artworks on the floor. In fact, prints could also be taken home by people.

The case of the Museum of Movements (MoM) project 2015-2020 in Malmö, from its ideation till the decision to discontinue its funding by both national and local governments, is worth mentioning here. A museum visualised as ‘national museum for democracy and migration in Malmö’, museum scholar Olga Zabalueva writes, ‘it existed both as a political endeavour on the pages of newspapers and municipal reports and as a real movement composed of all the potential stakeholders and collaborators.’10 Its vision of a museum had a bottom-up perspective, where civil society is represented, and power is shared.11 But a change in political priorities and conflicting interpretations of the mission and accepted format of a museum at both local and national levels led to MoM’s ultimate and premature disappearance—yes, absence.

As with the MoM, the revered armlängds avstånd (‘an arm’s length distance’) principle comes with frictions and its own set of limitations, which even ABSENCED wasn’t exempted from.

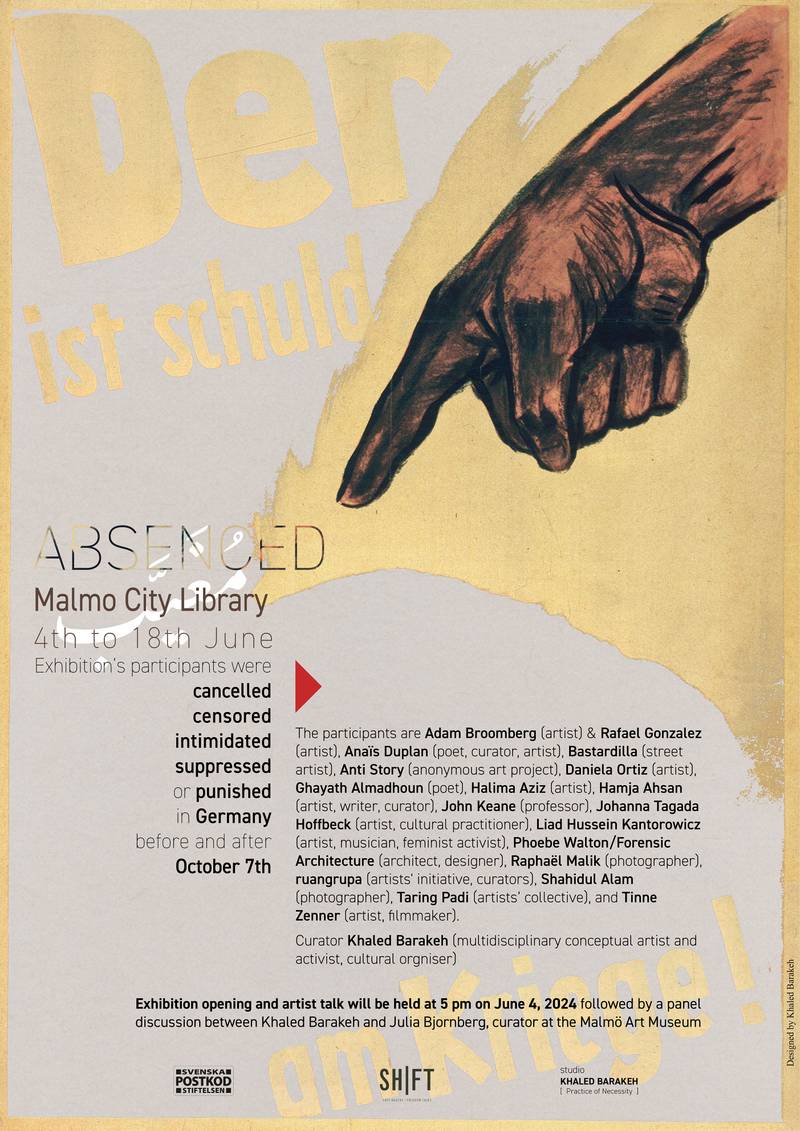

The press poster that Khaled wanted for the exhibition was turned down because it played on Germany’s history of blaming Jews for the Second World War. The poster had replaced the Jews targeted by the Third Reich with the Palestinians of today being targeted by the Israeli state’s violence, symbolised by a red triangle, a symbol of pro-Palestinian support and recently banned in Germany.

The initial poster designed for the exhibition ABSENCED.

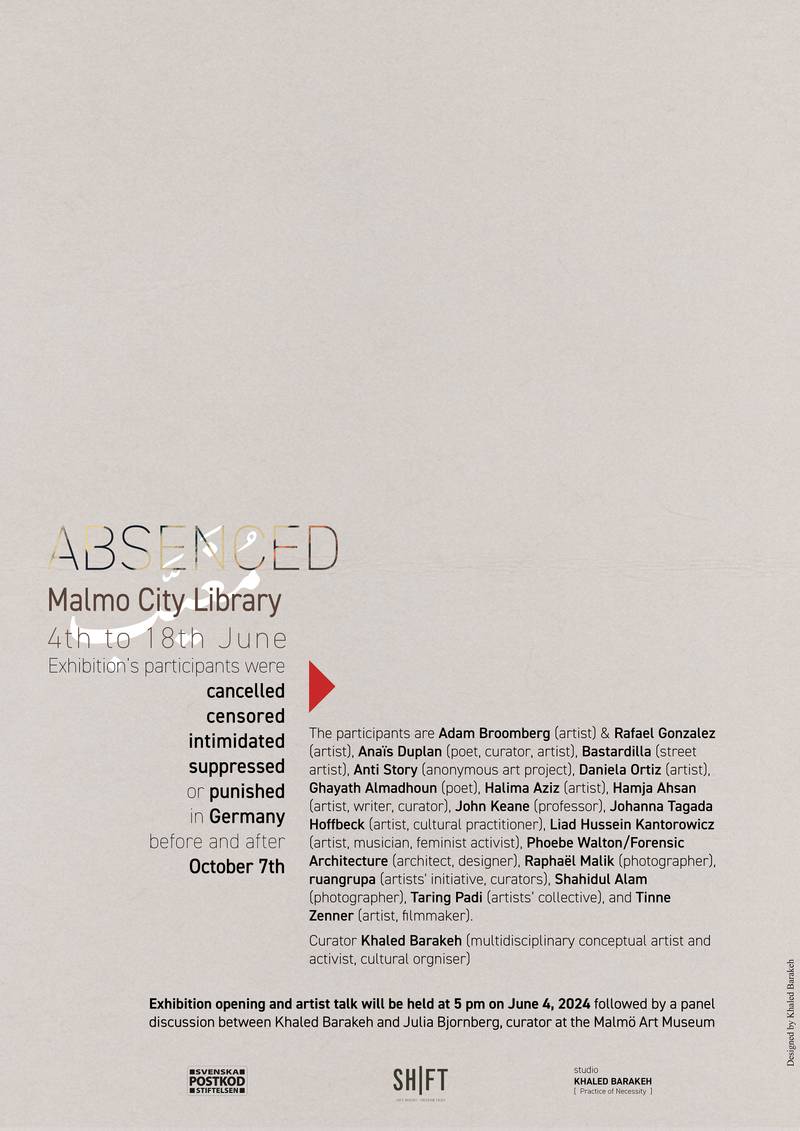

The final poster for the exhibition ABSENCED.

The symbol remained on the press release, but other depictions were taken away. Khaled’s intention in removing the phrase ‘am Kriege’ and retaining ‘der ist schuld’ alongside the accusatory hand was to underscore the act of generalising blame and the dangers of collective accusations. However, the decision to cancel the poster was in part informed by voices from within the artists’ collective represented in ABSENCED. In other words, while being united by their shared experiences of censorship, the group of artists held different opinions on whether the use of Nazi imagery in such a de-contextualised manner reflected their work and purpose. Regardless of this, the library wanted to play it safe, and the language ultimately chosen to describe the exhibition remained in a ‘neutral’ space. I do not mean to say that the library abandoned deliberation or democratic principles. However, it is important to note that the same ‘threat-to-all’ logic/understanding mentioned above is guiding these decisions. Because there was no agreement on the poster, the press release suffered a delay, in turn leading to library staff proposing a change in the venue or even cancelling the exhibition.

One of the groups of artists represented at ABSENCED, ‘Anti Story - Reversed Image’, is worth recalling here since their practice has circumvented such institutional dilemmas while keeping the edge of resistance strong and radical. In their words, they are an ‘open-source shared project, transcending the authority of any temporary political bodies or administrations. The crux of the project lies in inverting the colours of images and symbols to create a new visual spectrum that remains opaque to conventional understanding.’12

Artwork prints as seen on the floor of the exhibition display. ABSENCED. Slottet, Malmö City Library, Malmö. Image courtesy of Khaled Barakeh.

A library, as a public institution, being afraid of getting stormed by neo-Nazis and other violent groups is a legitimate concern for the safety of all visitors to the library. Also, having recently reported an accusation by a right-wing newspaper that disrupted the library’s day-to-day work, choosing a ‘safer outreach’ about the exhibition is understandable. However, the nature of response a public institution gives reflects the conditionality on which ‘freedom of speech’ and ‘universal positionality of an artist are judged.

Raphael Malik’s photo exhibition getting cancelled by Pixel Grain because of ‘the situation in the Middle East’ points to some similar fears at play. In showing ‘Muslim cultural style’ of many public spaces of Berlin, the fear of getting attacked, ostracised or losing funding sources, took precedence over the content and context of the artwork.

Similarly, Liad Hussein Kantorowicz’s multiple experiences of self-censoring as an artist since October 7th highlighted the degrees to which artistic freedom is challenged in Germany. Not only the statement ‘Free Palestine From the River to The Sea’ was censored but their music video piece ’Model Minority’, also represented in the exhibition, went through several rounds of censorship and ultimately ended up as an exclusive, closed-off VIP live performance.

...model minority

you won’t divide and conquer us

I don’t want your reparations

no apologies or declarations

you can take them back

til they’re given to all of us

talk about yourself, they say

talk about the you we know

but let us be the experts

holocaust, ‘Juden raus’, never forget

any mention of Palestine is russian roulette

that you’re playing with your own right to exist...

Here again, the message is that the damage that ‘you’ are doing is potentially harmful to the public, to the common, and even democracy. The discrepancy that I mentioned above reveals itself through the politics of neutrality, fear, and silencing. The exhibition ABSENCED has managed to drive this point home with its printed sheets of artworks loose on the ground but tied together in the discourse of what Germany perceives and defines as ‘antisemitic.’ This definition has recently become increasingly broad, giving advantageous power to German officials.

Second, when it comes to an art institute’s purposes, more liberal as well as socially responsible understandings are focused on creating entertaining experiences and participation of the public, yet always from the foundation of a ‘neutral’ ground. To name only one example, having recognised Palestine as a sovereign country only in October 2014, Sweden relies on universal order of rights, maintaining its ‘neutrality’ while also continuing the arms trade, business and other exchanges with Israel.13 However, this neutrality, often characteristic of Sweden’s policies, gets challenged when faced with the fact that Sweden has its own spectrum of political fringe movements, some of them controversial and dangerous, and some of their members taking an interest in public culture.

Last but not least, the library space has been good for the exhibition’s purpose, but in terms of visibility in conventional circuits of contemporary art and its subsequent criticism, art chatter has been rather missing on ABSENCED.

As I conclude this review, all active student encampments have been shut down or thrown out, but the protests on the streets of Sweden are still continuing. The last time such a student protest manifested in the country was in 1968.

Today, Sweden celebrates 50 years of the establishment of its first official cultural policy. Hosting the kind of exhibition that has recently become subjected to outright censorship in a country merely 150 kilometres from Malmö should call our attention to critique and watch Sweden’s current state regarding artistic freedom. More than that, it urges us to challenge and question what we want from our artistic institutions and who they represent. Having created ABSENCED under the ethos of what Barakeh terms ‘practice of necessity’, it stands as a reminder that producing art is a transcendental act, a necessary form of resistance. Although the display lasted only a few weeks, ABSENCED managed to trigger a conversation on a perhaps specifically Swedish naivety regarding ever-cherished notions of ‘neutrality,’ of extremism being located elsewhere, and a self-perception of an indisputable rule of artistic freedom of speech applying to everyone on Swedish soil.